The regulation of collective dismissals:

Economic rationale and legal practice

Abstract

This paper offers a legal and an economic analysis of collective dismissals procedures. First, it explains the economic rationale for having collective dismissal procedures in place, in light of the fact that labour markets are not perfect. Second, it overviews the international labour standards pertaining to collective dismissals for economic reasons. Third, using information for 132 countries, it reviews and compares legal practices of collective dismissals throughout the world in the light of the international labour standards. The paper shows that the statutory regulations of collective dismissals are in fact very different from regulations of individual dismissals, not only in the types of the legal procedures that they contain, but also in their economic objectives. The paper also discusses the caveats of making cross-country comparisons of the degree of worker protection, and of the costs to employers, provided by these regulations.

Introduction

Regulation of collective dismissals for economic reasons1 is one of the key pillars of employment protection legislation (EPL). Despite being a key labour market institution, EPL remains controversial, as manifested in both academic debates (for reviews, see Skedinger, 2010; Betcherman, 2012; 2014) and policy debates (for examples, see World Bank, 2013; IMF, 2016; OECD, 2007 and subsequent publications; ILO, 2015a). Interestingly, most of the debate has focused on only one EPL pillar – protection in case of individual dismissals.2 The collective dismissals pillar has received much less attention.

The objective of this paper is to contribute to fill this void. First, it reviews and compares legal practices of collective dismissals throughout the world in the light of international labour standards (ILS). Second, it discusses not only their legal aspects, but also the economic and social rationale. It shows that the statutory regulations of collective dismissals are in fact very different from regulations of individual dismissals, not only in the types of the legal procedures that they contain, but also in their economic objectives. Most importantly, the paper shows why collective dismissals is one of the areas that can particularly benefit from being regulated.

As is the case with provisions on individual employment termination at the initiative of the employer, provisions on collective dismissals usually reflect the de facto asymmetry of contractual rights of either party to terminate employment relationship, as well as the need to address the consequences of this asymmetry and to redress the unequal bargaining power between workers and employers (Buechtemann, 1992; Deakin, 2014).3 While termination of the contract by the worker – exercising the fundamental right to protect his or her freedom of work – is oftentimes merely an inconvenience for the employer, the termination of the employment relation by the employer can result in insecurity and poverty for the workers and their families, particularly during the periods of high unemployment (GS 1995; ILO, 2015a). The consequences of collective dismissals go beyond individual employers and workers and affect the economic health of communities. For this reason, they are particularly prone to market failures.

Market failure is a situation in which the individual incentives for rational behaviour do not lead to rational outcomes for the society. For example, it may be rational, optimal, and normal for a specific company to dismiss a group of workers. However, such choice may not necessarily be fully optimal for the society. Market failures may result from a variety of factors, such as negative externalities (the fact that collective dismissals may impact not only these workers, but also other workers of the area or sector, and their families), information asymmetries (enterprises and workers do not have the same knowledge about the economic situation of the enterprises), transaction costs (it may be too costly to have several individual dismissals as compared to a collective dismissal), and uncertainties. Thus, the specific rules governing collective dismissals (whenever they exist in national laws or practice) first and foremost aim at correcting such market failures, by incorporating social considerations into the individual decision-making. The challenge for a legislator, however, is not to impose regulations that unduly restrict collective dismissals, as this may also lead to the hesitation by enterprises to invest and create new jobs. Rather, it is to restore the socially-desirable optimum and improve labour market efficiency.

The rules governing collective dismissals contain many elements similar to the regulation of individual dismissals, including notably the necessity to provide a valid reason for dismissals. However, one of their main differences lies in a special procedure that needs to be followed to accomplish several terminations of employment. Such special procedural requirements may include but not be limited to: consultations of the employer with workers’ representatives, notifications to the competent authorities, undertaking measures to avert or minimize terminations and to mitigate their effects, establishing criteria for selection for termination and priority of rehiring. While they cannot always prevent job losses, these procedures aim at guaranteeing an orderly process, and striking the right balance between the needs of workers, employers, and societies at large4.

A novelty of this paper is to show how various factors that lead to market failures are addressed in the international and national laws and legal practice. As such, the paper highlights that assessments of the regulations of collective dismissals can particularly benefit from economic thinking, outside of neoclassical economics, including economics of information asymmetry, contract theory, and institutional economics. The paper shows that the alternative to collective dismissals is not the absence thereof, but several individual dismissals, which, without a specific procedure designed to address them, risk posing challenges not only to workers, but also to businesses and to societies, both in terms of administering them and in terms of dealing with their consequences. By doing so, the paper complements and extends (both in argumentation and in the number of countries covered) comparative overviews of collective dismissals’ provisions in legal scholarship (such as Collins, 2012; Countouris et al., 2016).

While this paper focuses on describing the logic, and comparing the regulations of collective dismissals across different countries, it is important to remember that, for any proper analysis of the impact of these regulations on economic outcomes (such as employment, unemployment, productivity, to name a few), such regulations should be placed in a wider context of economic, employment, vocational education and training, as well as social security policies (notably unemployment insurance, social assistance, early retirement). These contexts can have a significant influence on the concrete shape of collective dismissals provisions, as they may often complement or substitute them. Considering all such policies goes beyond the subject of the present study, and yet the absence of such comparison limits the scope of the identification of differences and commonalities across countries. Another limitation of the study is that it does not systematically analyze internal enterprise practices meant to prevent as much as possible the need for collective dismissals (e. g. working time savings accounts) or to mitigate the effects for dismissed workers (life-long-learning). It does, however, provide examples of such practices, for those countries for which such information is available. More generally, studying preventive approaches of employment protection that, while trying to limit interference with the functioning of companies/markets as much as possible, seek to avoid the need for collective dismissal or, where it cannot be avoided, to reduce the negative consequences of collective redundancies, is a very promising area for further research.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 1 provides economic and social rationale for various regulations and discusses what impact such provisions, as well as their absence, may have on various outcomes of workers, employers, and societies. Section 2 reviews ILS relevant to collective dismissals. Section 3 examines examples of national law and practices in comparison with the ILS. The last section concludes with thoughts on how to assess whether regulations actually do achieve their market-failure-correcting objectives.

Economic and social rationale of collective dismissal procedures

Economic theory, including the work of Nobel-prize winners Ronald Coase and George Akerlof, widely recognizes that labour markets are not perfectly competitive (for overviews, see Kaufman, 2007, or Lee and McCann, 2011). As Robert Solow has argued, the labour market is better understood as a “social institution” and thus the concept of perfect competition should not be applied to the labour markets at all (Solow, 1992). When basic assumptions of the neoclassical economic model are relaxed, such as by introducing transaction costs (Coase, 1937; 1960) and information asymmetries (Akerlof, 1970), there is an economic case for labour market regulations (Kaufman, 2007; Boeri and van Ours, 2008).

It is thus widely recognized that EPL in general exists because it helps to remedy market failures, created by transaction costs and externalities, but also by incomplete contracts that do not ensure workers fully against income losses (Pissarides, 2001; Bertola, 2009). EPL in general aims at improving the efficiency of the labour markets (Nickell and Layard, 1999; Boeri and van Ours, 2008). It can also provide more equitable outcomes, being an effective alternative to redistribution systems (ibid). Many countries adopted, and continue adopting, EPL as part of their development, recognizing that a balanced employment protection is likely to be compatible with longer-term development goals (Deakin, 2014; Deakin et al., 2014).

The sheer size of these negative externalities, transaction costs, and information asymmetries is substantially larger in case of collective dismissals than in case of individual dismissals. Given this, special collective dismissal procedures exist in many countries in addition to rules governing individual dismissals. They have at least six specific explicit goals to substantially reinforce the efficiency and equity objectives of the general EPL regime.

Addressing negative externalities of collective dismissals

First and foremost, special procedures for collective dismissals reflect the need to address important negative social and economic consequences that collective dismissals may have. Those are related to the fact that in collective dismissals, the social value of even one individual’s job can go beyond its private value (Cahuc and Zylberberg, 2006), and the value of worker’s human capital can be greater for a society than for an individual firm (Booth and Zoega, 2003). Depending on company’s size and the number of workers to be dismissed, collective dismissals affect not only individual workers, but also whole sectors of activity, labor market segments, and geographical areas. A relatively large collective dismissal may depress the local economy and, thereby, increase the likelihood of dismissals in other local firms. There may also be risks of poverty and social exclusion not only of the affected workers, but also of their families, and severe consequences for the health of the affected population, including stress over job loss, sleep deprivation, depressions, and even suicides (for a review, see Countouris et al., 2016). In addition, many workers entering suddenly into unemployment will interact in their job search activities, creating congestion, with negative effects on search efforts of new unemployed workers and decreasing their likelihood of finding a suitable job at a local level. Thus, the laws and practices of many jurisdictions regarding collective dismissals aim at avoiding systemic disruption of the labour market and of the local economy.

Internalizing costs of collective dismissals

The social costs of collective dismissals may include, but are not limited to, providing the economic support to the unemployed; expenses linked to retraining workers and helping them in finding employment; expenses linked to relocations of workers and their families; economic desertification of an area and consequences for other enterprises and sectors, including education and medical sectors, among others; as well as various hidden costs including health care and criminal justice (Collins et al., 2012). Thus, as a second objective, both ILS and the national laws and practices of many jurisdictions on collective dismissals explicitly aim at internalizing these costs, in other words, involving the employers in sharing the burden of costs with the society, with public authorities and public budgets. Moreover, research shows that cooperation between tripartite social partners with a view to anticipating and preparing restructuring processes can help to avoid or lessen the overall costs (Eurofound, 2011).

Improving risk-sharing and redistributing the losses

Since having all of the social costs borne by the employer may be not be possible, nor desirable, the third objective of the collective dismissals procedure is to redistribute the losses and share them equitably – not only between workers and societies, but also between employers and societies. For this reason, both ILS and national laws and practices also often explicitly aim at finding solutions to prevent such costs, jointly by the tripartite social partners. Social dialogue is key in this respect, as it can result in ingenious solutions to preserve jobs and improve outcomes for the workers, the employers, and the communities at large. Involvement of public authorities at the consultation, notification, and/or approval stages, if well designed, can help develop solutions to mitigate and better forecast the consequences of collective dismissals.

Reducing information asymmetries

The effective realisation of these objectives can only be possible if full information is available to all parties. Thus, the fourth objective of the procedure is to reduce information asymmetries between workers, employers, and also public authorities. This asymmetry is due to the fact that employers have more and better information on the economic situation of a firm that leads them to consider collective dismissals.

The information asymmetry is principally reduced at the notification and consultation stages of the collective dismissals procedures. Unless addressed, information asymmetry may create an imbalance of powers, aggravating market failures. The costs of such consequences are usually not incorporated (and cannot be incorporated) in individual private contracts between employers and employees. Rather, they are shifted to the taxpayers or to social security systems (Skedinger, 2010), hence again begging for involvement of the tripartite social partners in their avoidance. Moreover, the respect of the information and consultation procedures may also have other effects, such as reducing a “moral hazard” situation where, once the dismissal plan is agreed, but there was no information provided, or provided too late, the employer may have an incentive to conduct a dismissal differently from the one agreed upon.

Decreasing transaction costs

In the absence of a collective dismissals procedure, carrying out multiple individual dismissals may be quite costly for an employer. Thus, the fifth objective is to create a special avenue aiming at decreasing transaction costs of multiple dismissals. In most of the legal traditions, collective dismissals procedures are designed to respond to objective circumstances faced by an enterprise, and to accommodate the business needs by streamlining several individual dismissals into a constructive channel. The special procedure reflects the recognition of the necessity to provide the employers with an efficient way to terminate the employment of workers by preserving their businesses and competitiveness, taking into account the requirements of the enterprise (GS 1995, p.106). It offers a possibility for employers to find solutions jointly with workers and their representatives over the number of separations, the type of separations (some workers may accept voluntary departures), the schedule, and the list of workers concerned. As the procedure often includes the possibility of selecting and rehiring employees, employers may be in a position to strengthen their productive capacities.

Public authorities may also play a positive arbiter role in facilitating and streamlining terminations for economic reasons, especially where social partners cannot find an agreement. They often have special competence and experience to handle sensitive dismissal issues and to plan many of their aspects.

Many good practices aim at rendering collective dismissals sensible and fair. When several individual terminations need to be effectuated, collective dismissals procedure aims at offering a transparent and fair alternative, which can help mitigate the adverse psychological climate in which redundancies take place, and thus help preserving company’s productivity and reputation. Effective management of collective redundancies may also help maintain trust and provide a decent basis for restructuring the business, helping employers to preserve their uniqueness rather than re-starting their business from ground zero.

Reducing uncertainties

Last but not least, because both individual and collective dismissals may be challenged in courts by workers and unions, the expectation of a certain court’s decision will directly impact the likelihood and the content of individual worker’s actions against their own dismissal. Collective dismissals procedure conducted in an open manner and involving genuine negotiations can reduce litigation risks and their uncertain legal outcomes, which is of value for both workers and employers (Oyer and Schaefer, 2002). For example, some authors show that the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 in the US has affected the methods of displacement used by American firms (Oyer and Schaefer, 2000). To the extent that it was legally possible, some firms preferred to implement a collective dismissal procedure instead of many successive individual dismissals, in order to avoid high costs of wrongful termination litigation. If many workers were to be dismissed at the same time through a special procedure, it would be very difficult to prove discrimination in courts thereafter (ibid; Malo and Pérez, 2003). Thus, one of the outcomes of the special collective dismissals procedure is often a legitimization of the whole dismissal program.

In light of the above, any assessments of the impacts of collective dismissals procedures need to take into account their positive and negative effects on workers, on employers, and on the societies. They should also strive to see what the counterfactual would have been. In other words, any assessment needs to address the extent to which terminating several workers through a collective dismissal procedure is indeed more efficient and optimal for enterprises and for the societies than several terminations through an individual dismissal procedure.

Collective dismissals: Overview of provisions contained in the ILS

Which ILS are relevant for collective dismissals?

The Termination of Employment Convention, 1982 (No. 158) and the Termination of Employment Recommendation, 1982 (No. 166), thereafter C158 and R166, are the main ILO technical standards addressing the termination at the initiative of the employer. They provide important guidance on the regulation of both individual and collective dismissals.

C158 and R166 stipulate that national governments may, in consultation with employers’ and workers’ organizations, put in place special procedural requirements for terminations of employment for economic, technological, structural or similar reasons, whether they concern

As per March 2020, C158 has been ratified by 35 out of 187 ILO member States.5 The moderate level of ratification of this instrument may be explained by different factors. One of them is that the Convention currently has a “no conclusions” status6 and is not promoted for ratification on a priority basis (ILO, 2009a). Another is the persistent debate on the role of EPL, which is often reduced to seeing EPL as purely a cost to the employer, without recognizing its beneficial aspects (for a review of both advantages and downsides of EPL, see Skedinger, 2010). Nevertheless, the level of ratification of C158 is comparable to other technical ILO conventions.7

Such special procedural requirements may include, but are not limited to: consultations of workers’ representatives, notifications to the competent authorities, undertaking measures to avert or minimize termination and to mitigate their effects, establishing criteria for selection for termination and priority of rehiring. The ILS explicitly recognize the importance of involving the tripartite parties in the deployment of these measures.

The ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), in its general observation on C158 in 2008, noted that, regardless of whether the Convention 158 is ratified or not, the basic principles of these standards are actually embedded in the legislations of a wider set of countries, including “notice, a pre-termination opportunity to respond, a valid reason and an appeal to an independent body” (ILO, 2009a).

Although they do not refer directly to collective dismissals for economic reasons, several other ILS outline important employment protection principles for some categories of workers. These instruments include both fundamental conventions and several technical conventions and recommendations (Box 1).

The ILS are the key benchmarks against which national laws can be meaningfully compared, regardless of whether they have been ratified or not. The current paper does not intend to measure the national laws’ ratification and implementation of ILS, but rather identify to what extent national legislations contain provisions outlined in these standards (especially the two specific technical standards governing employment termination: C158 and R166). This is different from comparing regulations against a benchmark of “no provisions”, or “minimum” provisions in a given sub-sample of countries, as may be done elsewhere. Using ILS as a benchmark for cross-country comparisons is legitimate, since ILS are one of the key sources of national labour laws.

Box 1. Other ILS relevant to the regulation of termination of employment

In parts addressing specifically terminations on economic grounds, both individual and collective, C158, Art. 13(3) and R166, Para. 20(3) make explicit reference to Workers’ Representatives Convention, 1971 (No. 135). This instrument stipulates that workers’ representatives in enterprises have to enjoy effective protection against any act prejudicial to them, including dismissal, based on their status or activities as a workers' representative or on trade union membership or participation in trade union activities, in so far as they act in conformity with existing laws or collective agreements. The Workers’ Representatives Recommendation, 1971 (No. 143) also details specific measures that should be taken to ensure effective protection of workers’ representatives.

In addition, two fundamental ILO conventions are of relevance to collective dismissals. One is The Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98), according to which trade union membership, participation in union activities outside working hours or, with the consent of the employer, within working hours (C098, Art. 1) constitute prohibited grounds of dismissal (anti-union discrimination). Another is The Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111). It defines the term “discrimination” as including any distinction, exclusion or preference made on the basis of race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction or social origin, which has the effect of nullifying or impairing equality of opportunity or treatment in employment or occupation. Those constitute prohibited grounds for dismissal (discrimination: Art. 1, 1(a) of Convention No. 111). Convention No. 111 also includes additional principles in Art.5. It also stipulates that all persons should, without discrimination, enjoy equality of opportunity and treatment, in particular in respect of security of tenure of employment. With regards to collective dismissals, that these non-discrimination principles be also respected when determining criteria for selection of employees to be dismissed and priorities for rehiring.

Among technical conventions, The ILO’s Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183), in its Article 8, declares unlawful for an employer to terminate the employment of a woman during her pregnancy or maternity leave or during a period following her return to work to be prescribed by national laws or regulations, except on grounds unrelated to the pregnancy or birth of the child and its consequences or nursing. Under the ILO’s Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156), family responsibilities may not, as such, constitute a valid reason for termination of employment. In addition, the marital status and family situation should not as such, constitute valid reasons for termination of employment. Measures and national regulations in respect of pregnancy, maternity, and family responsibilities are all considered to be essential for promoting gender equality in employment, and hence to eliminating sex discrimination, which constitutes prohibited ground for dismissal under fundamental Convention No. 1118. The HIV and AIDS Recommendation, 2010 (No. 200), states that real or perceived HIV status should not be a cause for termination of employment (Para. 11). Lastly, the Violence and Harassment Recommendation, 2019 (No. 206) suggests that appropriate measures to mitigate the impacts of domestic violence in the world of work could include temporary protection against dismissal for victims of domestic violence, as appropriate, except on grounds unrelated to domestic violence and its consequences (Para 18c).

Definition of collective dismissals for economic reasons: substantive and quantitative aspects

Strictly speaking, C158 and R166 do not refer to the term “collective dismissals” as such. Rather, both contain a special part (Part III in both) entitled “Supplementary provisions concerning terminations of employment for economic, technological, structural or similar reasons”. Article 13 (2) of C158 provides that “National laws or regulations may limit the applicability [… of these provisions] to cases in which the number of workers whose termination of employment is contemplated is at least a specified number or percentage of the workforce”. Thus, C158 leaves it to the national regulators to determine whether such procedures are to be applied in the case of

Importantly, according to the General Survey of the ILO CEACR (GS 1995), the fact that the special procedures for terminations of employment for economic, technological, structural or similar reasons are contained in “Supplementary provisions” part of the Convention does not mean that they are secondary. The word “supplementary” is used in the meaning “additional”; “additional” to other provisions of the Convention (GS 1995).

Special procedures triggered in case of collective dismissals: information and consultation of workers’ representatives

ILS stipulate that when the employers contemplate collective dismissals, they should foresee providing the workers' representatives with the

The

The

As clarified by the General Survey of 1995, “finding alternative employment” is the only explicitly prescribed measure of the

ILS also stress the importance of the

Special procedures triggered in case of collective dismissals: notification to competent authorities

According to ILS, employers contemplating terminations for economic, technological, structural, or similar reasons, should notify competent authorities of such intentions. ILS provide guidance as to the

The key objective of the notification is to give public authorities a possibility to play a mediator role between employers and workers in finding agreement and appropriate solutions, and mitigate its effects both for the affected workers and for the wider community. Thus, notification is a first step towards ensuring that public authorities can effectively play such roles during and after collective redundancies. The role of public authorities often goes well beyond simply taking note of terminations’ notification. It involves, among others, carefully elaborating social measures, securing funds for alternatives to dismissals (such as work-sharing) and for mass claims of unemployment benefits, preparing job placement centers. Indeed, R166, Para. 19 (2), states that “where appropriate, the competent authority should assist the parties in seeking solutions to the problems raised by the terminations contemplated”. Training and retraining options should be considered by public authorities with the collaboration of the employer and the workers' representatives concerned [R166, Para. 25 (1)].

Special measures to avert or minimize dismissals for economic reasons and to mitigate their effects

ILS explicitly provide that the procedures contained therein serve the objective of averting or minimizing termination of employment and mitigating its effects [C158, Art. 13 (1b); R166, Para. 19(1)]. R166 also puts forward a set of specific measures to reach this objective, including the obligation of the employer to consider other measures before termination of the employment; criteria to be applied in selecting workers whose employment is to be terminated; and priority rules for rehiring dismissed workers.

The ILO CEACR in its General Survey of 1995 reminds that “it is important to ensure that certain protected workers, such as workers’ representatives, are not dismissed in an arbitrary manner on the pretext of a collective termination of employment” (Para. 335). In this context, the special regimes of protection for several categories of workers (e.g. trade union members, workers’ representatives, women on maternity leave) are not to be neglected.

Obligation of the employer to consider other measures before termination of the employment

R166, Para. 21, contains a non-exhaustive set of measures which should be considered with a view to averting or minimizing terminations of employment. It provides that such measures “might include, inter alia, restriction of hiring, spreading the workforce reduction over a certain period of time to permit natural reduction of the workforce, internal transfers, training and retraining, voluntary early retirement with appropriate income protection, restriction of overtime and reduction of normal hours of work.” Furthermore, Para. 21 provides that “where it is considered that a temporary reduction of normal hours of work would be likely to avert or minimize terminations of employment due to temporary economic difficulties, consideration should be given to partial compensation for loss of wages for the normal hours not worked, financed by methods appropriate under national law and practice”.

Criteria for selection of employees to be dismissed

R166, Para. 23 (1), provides that there be specific criteria for selection of workers whose employment is to be terminated for reasons of an economic, technological, structural or similar nature. These criteria should be “established wherever possible in advance, which give due weight both to the interests of the undertaking, establishment or service and to the interests of the workers”. The determination of these criteria, of their order of priority and of their relative weight is left to national practice.

Priority of rehiring

R166, Para. 24 (1), provides that “[w]orkers whose employment has been terminated for reasons of an economic, technological, structural or similar nature, should be given a certain priority of rehiring if the employer again hires workers with comparable qualifications, subject to their having, within a given period from the time of their leaving, expressed a desire to be rehired”. R166, Para. 24 (2), also states that such priority of rehiring may be limited to a specified period of time.

Collective dismissals: Overview of national laws and practice

Sources of information on national laws and practice

The examples of national law and practice provided in this section are drawn from the ILO EPLex database9, as well as from other ILO publications, and publications of the ILO staff. Where appropriate, some arguments of this paper are also supplemented by examples found in the literature.

Our objective in this paper is to make a comparative analysis of legal regulations in as many countries as possible in order to advance convincingly our legal and economic arguments. However, such cross-country legal information is not easily available, and when it is, it may be available for different time periods in different countries. In order to reach the largest comparison base, we chose the year 2010. This is the year for which we have the largest number of country-specific observations from two sources combined: the ILO EPLex database - the official ILO database dedicated to the topic of employment termination - and Muller (2011), an ILO publication. Unless stated otherwise, exact details of laws are contained in these sources. In total, our comparative analysis is based on the information for 132 countries with available data. All maps and tables in this paper are based on this sample.

We are aware that some readers may find this information outdated. However, first, what matters for us in this paper is not the exact wording of the laws today, but the diversity of experiences and examples that can be found on the international level. The key point of this paper is precisely to analyze how counties compare (and differ) in the variety of legal tools that they use to regulate the same phenomenon, to show the ingeniousness of the legislators, and to show that sometimes the same objectives may be reached by different tools. Second, in fact, much of the legal information presented here is still of relevance today. This is because collective dismissals is a legal area where reforms are not frequent. Indeed, at the revision stage of this paper, we verified the ILO EPLex database. At the moment of writing, 57 countries contained information updated till the year 2018 or 2019. Out of them, only 6 experienced reforms of collective dismissals since 2010, or 10,5 per cent. Appendix 1 lists all countries with this latest available information, and records which countries experienced reforms. The details of the reforms are also provided in Box 2. Summing up, as this paper is the first attempt to analyze a cross country data on collective dismissals, the comparison base of the year 2010 is still useful for exploratory purposes, with much of the information still being meaningful.

Box 2. Examples of recent reforms of collective dismissals procedures

Two countries experienced major reforms of EPL in the context of the global economic crisis that started in 2008. In Spain, the reform of 2012 (Royal Decree-Law 3/2012) focused, among other issues, on collective dismissals, and in particular on the abolition of the administrative approval in the procedure for adopting collective dismissals. Also, the valid reasons for redundancies were clarified, to include current or foreseen losses, as well as a persistent decrease (at least three consecutive quarters) in ordinary revenue or sales, even when a company receives profits (Valverde, 2017; ETUI, 2016a; ILO EPLex).

In Portugal, the government, on the recommendation of international financial institutions (the “Troika”), changed labour laws several times in 2011-14. The area of collective dismissals was one of those affected by these changes (Vilarinho Marques & Mendes Ferreira Roberto, 2017; ETUI, 2016b; ILO EPLex). The Law 23/2012 concerned changes to seniority rules previously applicable to determining the order in which workers were terminated; changes to the justification of dismissals; and elimination of the obligation to transfer the employee to another suitable position. However, the Constitutional Court considered some of these rules to be unconstitutional (Decision 602/2013), which led to a reversal of the reform (Law 27/2014).

Both countries - Portugal and Spain – have ratified Convention No. 158. The reforms in response to the economic crisis were commented by the CEACR, as these cases reflect the interference of several factors affecting tripartite social dialogue on labour market reforms and the intervention of public and judicial authorities in the implementation of labour laws.

Similarly, in the Netherlands, several important labour market reforms occurred in 2013-2015. In 2013, a tripartite Social Pact was concluded on rebalancing flexibility and security, and this was followed by the adoption of “Work and Security Act” in 2014. Since the entry into force of the law in 2015, the preventive system remains, but the employer cannot choose freely between the cantonal judge and the public administration body [UWV). Dismissals for economic reasons must be decided by the UWV, in addition to some changes related to severance pay (Boot and Erkens, 2017; ETUI, 2016c; Dekker, Bekker and Cremers, 2017).

Examples of other reforms of collective dismissals over the 2010-2018 period include Romania in 2011 (Uluitu, 2017), the United Kingdom in 2013 (Neal, 2017), and Greece in 2011 (ILO EPLex).

This section presents a variety of legal practices of regulating collective dismissals. It also shows that there are several countries in which specific provisions on collective dismissals do not exist in statutory laws. Interestingly enough, while C158 allows each member State to determine the specific requirements necessary to apply its provisions, so as to respect different industrial relations traditions and specific features of national labour markets, in the developed countries there is more similarity than divergence across countries with respect to collective dismissals procedures (similar findings are also reported in Countouris et al., 2016; OECD, 2013). In the European Union countries, in a large part this is due to the European Council Directive 98/59/EC of 20 July 1998 on the approximation of the laws of the member States relating to collective redundancies, which has been transposed into national legislation of 27 countries (Box 3). The key differences across countries are embedded in the implementation practices, the definitions and content of the provisions, the roles of various competent bodies and of courts, different historical powers of tripartite actors, compliance and enforcement (ibid).

Box 3. Regional regulation as a source of national labour laws

The European Council Directive 98/59/EC of 20 July 1998 on the approximation of the laws of the member States relating to collective redundancies, which has been transposed into national legislation of 27 countries, contains requirements similar to the ones outlined in C158 and R166. It provides that any employer considering collective redundancies must hold with the workers’ representatives consultations in good time with a view to reaching an agreement. It provides that consultations must at least cover the ways and means of avoiding collective redundancies or reducing the number of workers affected and mitigating the consequences through accompanying social measures aimed notably at aid for redeploying or retraining those workers made redundant. The quantitative definition of collective redundancies has also been provided in the Directive.

Definition of collective dismissals for economic reasons: substantive and quantitative aspects

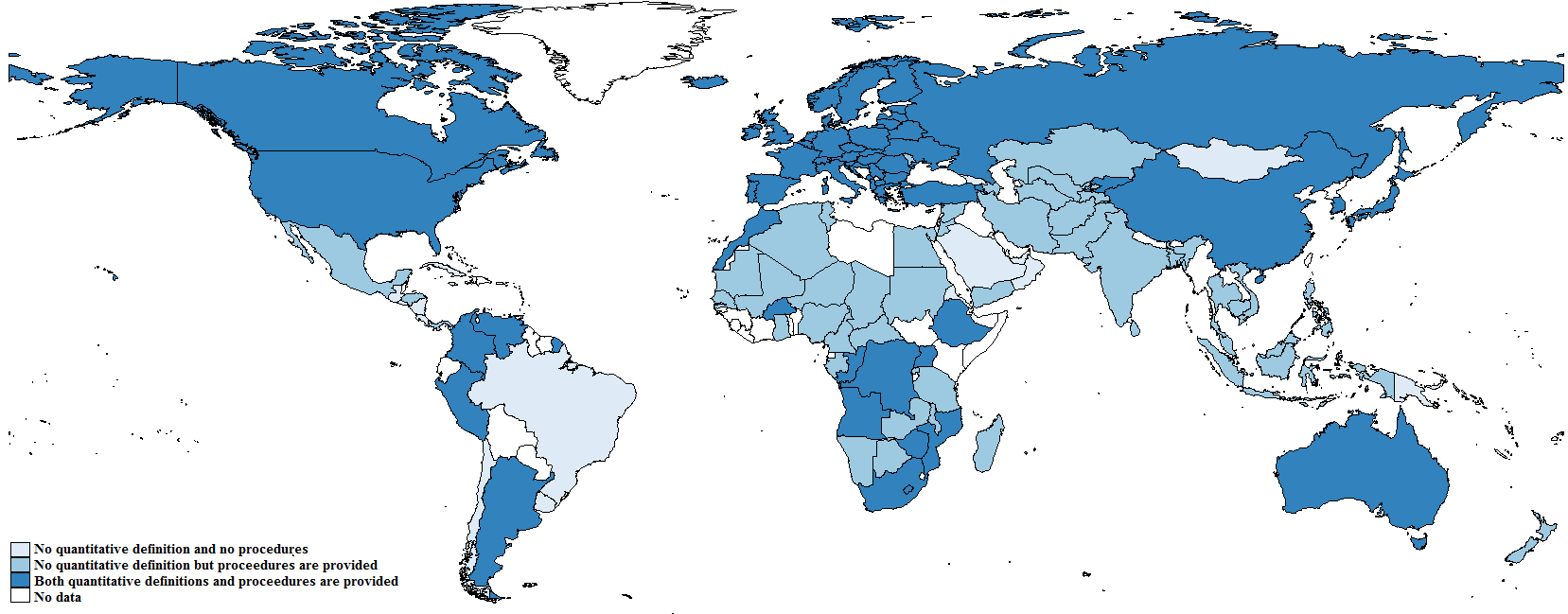

Definitions of collective dismissals vary tremendously across countries. In the 132 countries with available information, 22 countries have formal laws that contain neither the definitions of collective dismissals, nor any additional specific procedures for terminations of workers on the grounds of economic, technological, structural or similar reasons, beyond procedures previewed for any individual dismissal. In 50 countries, there is no definitional distinction between collective and individual dismissals on economic grounds (the statutory law does not contain any numerical threshold or time limit); however, specific procedural rules are provided. In other words, such special provisions are applied for terminations for economic, technological, structural or similar reasons regardless of the number of employees involved. In the largest group of 60 countries, laws provide for specific thresholds limiting the applicability of the Parts III of C158 and R166. Stated differently, they contain both substance and quantity components of the definitions for collective dismissals (Figure 1).

The substance component of the definition implies that collective dismissals are dismissals based on economic, technological, structural, or similar reasons. Normally, they cannot be based on worker-related reasons, such as worker’s capacity or conduct, but only on the operational requirements of the undertaking, establishment or service. Only the operational requirements of the enterprise are recognized as a valid reason for collective termination of employment.

Examples of scenarios in which collective dismissals may take place include employer’s insolvency or cessation of activity, cessation of a job, scaling down of an enterprise, or an enterprise’s transformation. Depending on a jurisdiction, each of these scenarios may trigger a different employment termination procedure. This is especially the case of insolvency or the cessation of the enterprise activity, which may be governed not only by labour law, but also by civil law and specific bankruptcy provisions.

Figure 1. Legal definition of collective dismissals for economic reasons triggering specific procedures

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

The ILO CEACR stresses the importance of the manner in which the termination of an employment relationship is defined. If the termination of the employment relationship at the initiative of the employer “is wrongly labelled by him [or her] for example as resignation, breach of contract, retirement, modification of the contract, force majeure or judicial termination, the rules of protection governing termination might apparently seem not to apply; but the use of such terminology should not enable the employer to circumvent the obligations with regard to the protection prescribed in the event of dismissal.” (GS 1995). While this quote applies generally to the dismissal at the initiative of the employer, the same can be said about the choice over collective versus individual dismissal procedure.

Given this, it is important to ensure, both through laws that include the right incentives, but also through enforcement policy measures, that employers do not deliberately stagger or scatter redundancies, when this is done exclusively with the aim of avoiding specific procedures such as notification and/or consultations10. For this reason, voluntary redundancies (employees volunteering to be considered for redundancy) are usually included in the total number in order to determine whether a collective dismissals procedure is to be followed11. Depending on a jurisdiction, when a separate redundancy situation within the same organization is taking place, additional dismissals may or may not be taken into account when considering new proposal to make employees redundant. While there is not much guidance on the supranational level on how to deal with issues of deliberate mislabeling of dismissals or their scattering, some legal systems have robust jurisprudence allowing to prevent or to revert the process. In some instances, such as in Italy before the recent labour reforms of the mid-2010s, it was not uncommon to reinstate workers terminated individually and to request that employers follow a collective dismissals procedure.

The way the collective dismissals unfold may also depend on who decides that it is to take place, for example, if it is a decision taken unilaterally by management, or did it involve a works council. When the decision is at the employer’s discretion, judges may be more likely to evaluate the validity of economic grounds for dismissals. Whether the presented economic grounds are indeed valid or not may depend on the extent to which reductions in profits or sales were expected or anticipated, whether the reductions are current or past. Some of the recent reforms dealt precisely with such elements of substantive definition of collective dismissals. Examples include the 2012 labour law reform in Spain, where the definition of dismissals on economic grounds was broadened and the concept of “negative economic situation” was clarified.

The

When quantitative definitions exist, they most frequently relate either to a

Table 1. Examples of quantitative definitions

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

EU countries that (literally) transposed the European Union Directive 98/59/CE of 1998 |

Over a period of 30 days |

At least 30 in establishments normally employing 300 workers or more |

|

Or, over a period of 90 days |

At least 20, whatever the number of workers normally employed in the establishments in question |

|

|

Angola |

Over a period of 3 months |

5 or more workers |

|

Argentina |

No time period specified |

More than 15% of workers in undertakings employing less than 400 workers More than 10% of workers in undertakings employing between 400 and 1000 workers More than 5% of workers in undertakings employing more than 1000 workers |

|

Armenia |

Over a period of 2 months |

At least 10 workers or more than 10% of the workforce |

|

Australia |

No time period specified |

15 or more employees |

|

Canada |

Within a period not exceeding 4 weeks |

At least 50 employees in an industrial establishment |

|

China |

No time period specified |

More than 20 employees, or less than 20 but accounting for at least 10% of the total number of employees |

|

France |

Over a 30-day period |

Different provisions regarding whether less than 10 or more than 10 employees are concerned |

|

Japan |

Over a period of 1 month |

30 employees or more |

|

Morocco |

No time period specified |

All or part of the workers in undertakings with 10 or more workers |

|

Peru |

No time period specified |

More than 10% of workers |

|

South Africa |

No time period specified |

For employers with more than 50 employees who contemplate to dismiss at least: |

|

United States |

Over a period of 30 days |

|

|

Zimbabwe |

Over a period of 6 months |

Five or more employees |

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. Note that, as shown in Appendix 1, the information was the same for Argentina, Armenia, Australia, China, Morocco, and South Africa in 2019; and for Japan and Zimbabwe in 2018, the latest year of available data.

From the economic point of view, provisions such as those defining quantitative definitions of collective dismissals are often setting a more objective scene for the procedures to unfold, and decrease uncertainty about the nature that the dismissals will have. They also serve a safeguarding role for disguised collective dismissals. Thresholds also matter if the dismissal process involves negotiations over the number of employees to be dismissed and over the alternatives to dismissals to be sought.13

Special procedures triggered in case of collective dismissals: Information and consultation of workers’ representatives

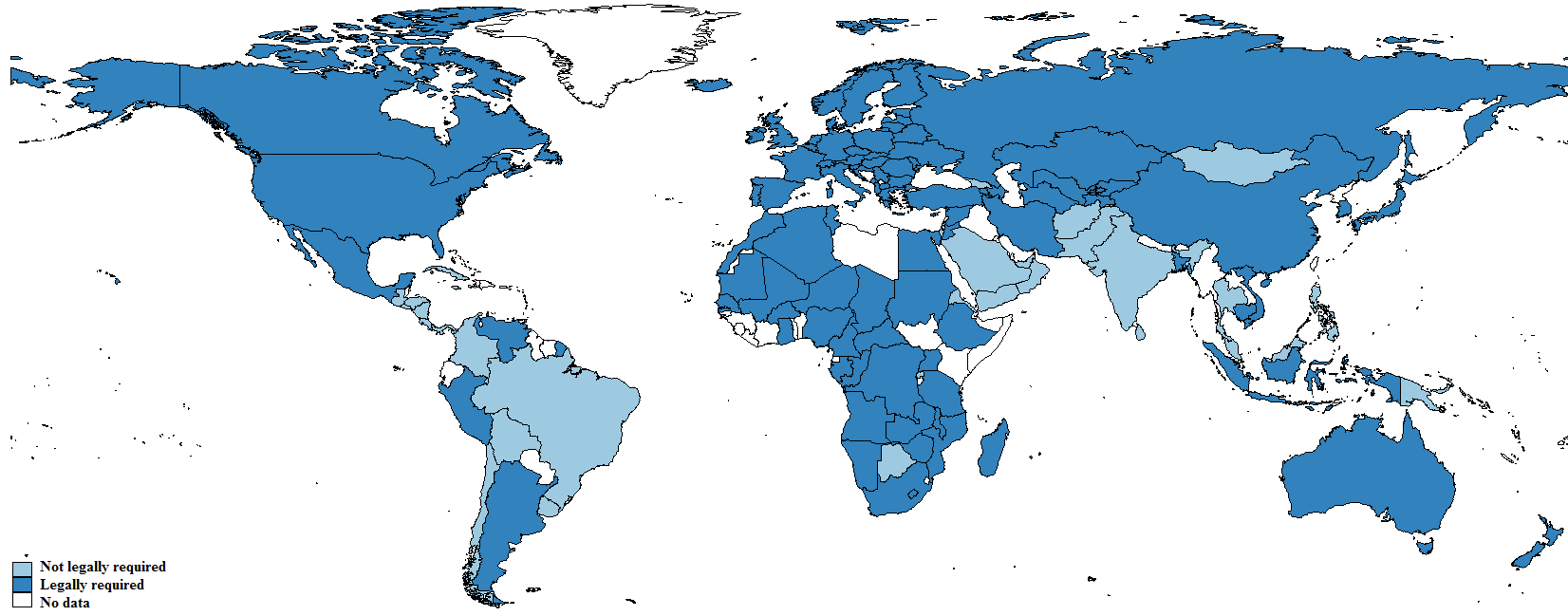

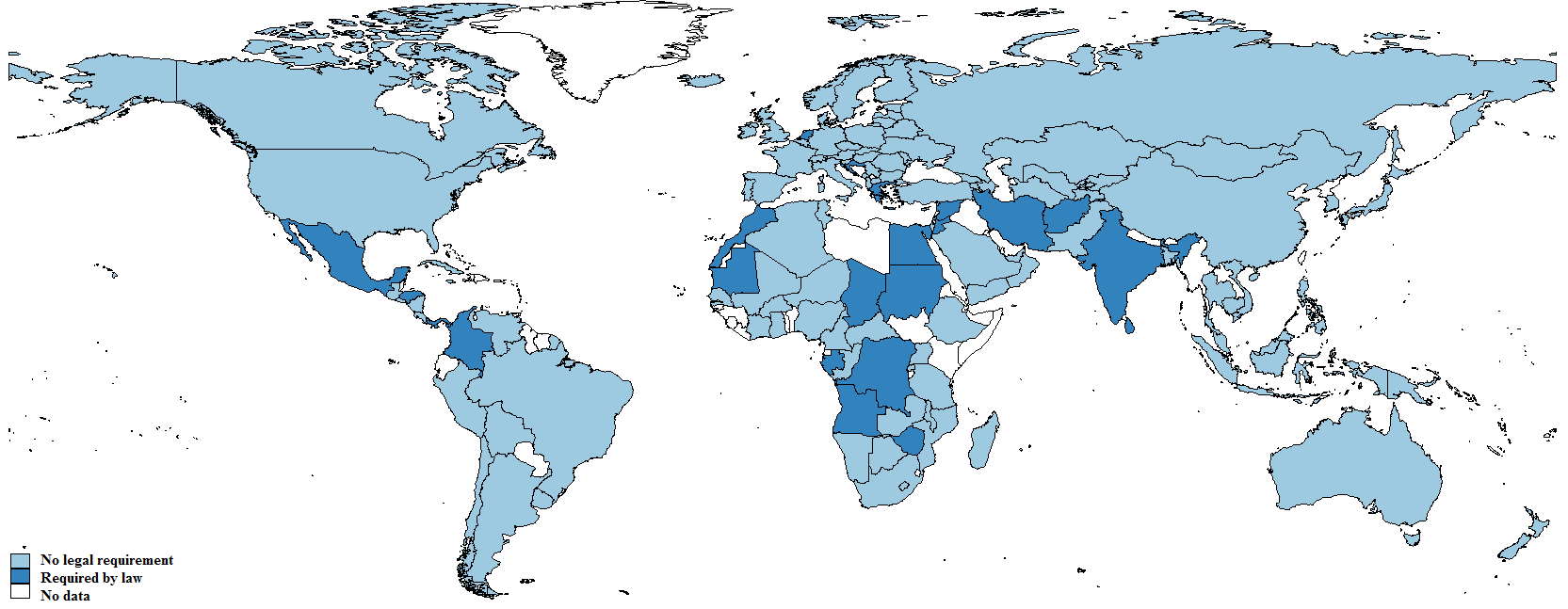

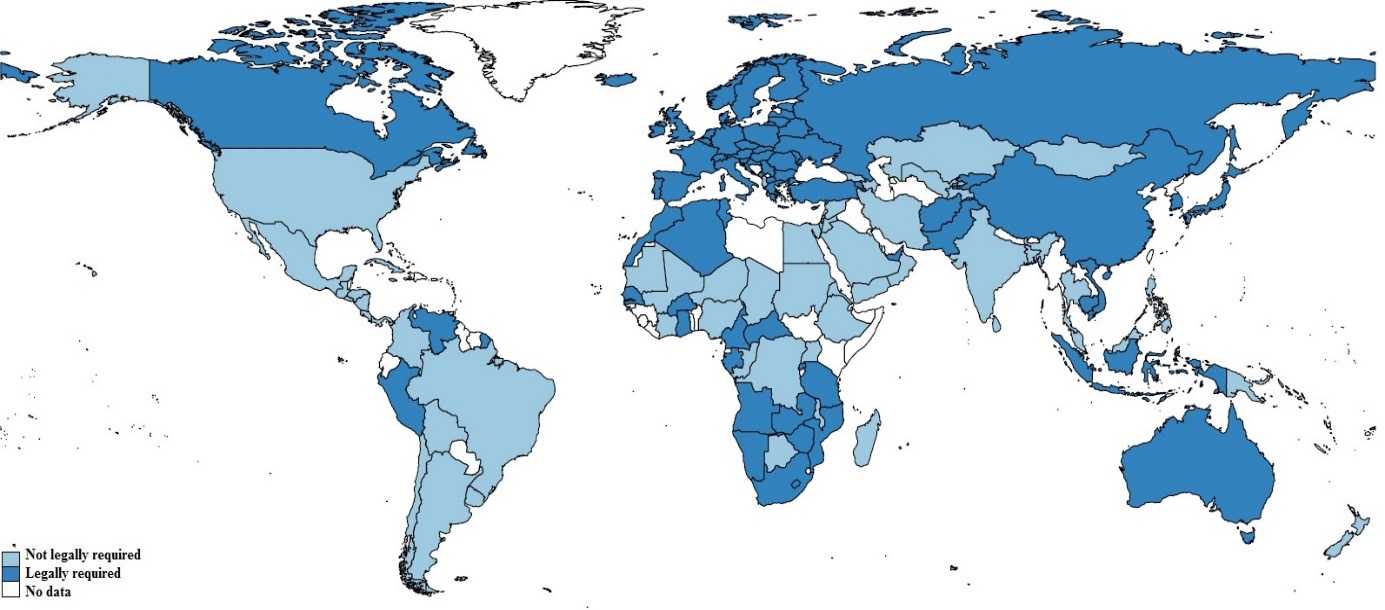

Providing information to (notifying) workers’ representatives is legally mandated in 97 countries out of 132 countries with available information (Figure 2). In other words, out of 110 countries that have any specific procedures related to dismissals on economic grounds, whether with or without quantitative definition of dismissals, almost 85 per cent contain this legal requirement. Consultation is legally mandated in 87 countries (Figure 3). The ten countries in which notification to workers’ representatives, but not the consultation, is a legal requirement are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Comoros, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, Nigeria, Sudan, Uganda, and the United States of America.14 However, even if a legal requirement to notify and consult is absent, information and consultation may exist in practice and be regulated by collective agreements.

A particularly high value is accorded by the law to sharing information and carrying out consultation in a transparent way as a means of “moderating or reducing the social tensions inherent in any termination of employment for economic reasons” (GS 1995).

Figure 2. Information to workers’ representatives: legal requirement

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

The

The economic and social rationale for legally defining the content of the information is to help mitigate significant psychological risks of workers, even those who will not be dismissed. The extent of information’s completeness may also be an important means to keep workers motivated and engaged during the dismissal process, and protect their well-being (ACAS, 2014). Employee motivation, in turn, is essential to maintaining a sound social climate propitious to the continuation of the employer’s activities that are both productive and prone to innovations (Acharya et al., 2013). Given this, for employers, the alternative to not providing information is not an “easier” dismissal procedure, but possibly an adverse social climate, disloyalty, strikes, lower productivity of remaining workers, sizeable production disruptions and potentially hurt image and reputation loss for the company. Similarly, the absence of social measures proposed by the enterprise may also affect its reputation, hurting its business, while a well-designed social measure may be used as a public relations strategy.

Figure 3. Prior consultations with workers’ representatives: legal requirement

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

In practice, however, providing full information may be challenging. Some information may be commercially sensitive, and hence not readily available for disclosure. It is thus important for the employers to strike the right balance as to which information to provide. In this respect, the laws often serve as providing only the minimum guidance, while the information actually provided in practice may be substantially richer.

The

In some countries, laws and practices make a distinction between consultations and negotiations. When

In some jurisdictions, the laws may prescribe that the consultations not only aim at averting or minimizing terminations, but also that they mitigate the adverse effects of terminations. The legislation of several countries contains legally binding requirements for employers to come up with accompanying social measures (Box 4). Such measures may have different names, but are frequently referred to as “social plans” or “programs of settlement of the manpower problems” (see, for example, Cosio et al., 2017).

Box 4. Social plans

Social plan is a set of social measures that accompanies collective dismissals. Examples of such measures include job placement assistance, additional payments for early retirements, individualized “severance packages” (which may be over the legal requirements), and provision of vocational training grants to workers (for other examples, see ACAS, 2014; NERA, 2016).

In many jurisdictions, elaboration of a social plan is a legal obligation for an employer contemplating collective dismissals. Examples include, among others, Algeria, Cambodia, Gabon, or Morocco (ILO EPLex). In Austria, a social plan (Sozialplan) is a legal instrument of collective labour law (Gerlach, 2017). In France, the social plan was reformed into the “employment safeguard plan” (Plan de sauvegarde de l’emploi) which includes measures to facilitate the redeployment of dismissed workers (Blatman, 2017). In the Netherlands, further to the 2015 reform, it is possible to sign a collective labour agreement (CLA) which stipulates that instead of the public administrative body, a CLA-Commission may decide on the application of dismissals for economic reasons. The CLA must be chaired by an independent personality and the CLA can provide for applicable criteria in addition to the official ones (Boot and Erkens, 2017). In Slovenia, the Supreme Court on several occasions has affirmed that the employer has to adopt a social plan which is a formal act with obligatory content (Blaha, 2017).

Depending on the extent of the social consequences of a collective dismissal, and on the role of the trade unions (workers’ representatives), the development of a social plan may or may not be the object of consultations, and possibly involve public authorities. In some cases, a social plan can be agreed upon with a works council without presenting it up to negotiations with trade unions (workers’ representatives), or even decided upon unilaterally by the employer. The participation of the State authorities in the elaboration of a social plan often guarantees such additional measures as training programmes to workers and wage subsidies to recruiting employers.

Depending on the scale of collective dismissals, a social plan may have to be defined for a specific region, and may last for several years. Stark examples of the latter include social plans for “mono-cities” – localities that strongly depend on one employer, which are a legacy of the Soviet regime in former USSR republics.

In the majority of countries, there is no specific

The length of the consultation may or may not be limited in the laws of different countries. Minimum limits can help ensure that enough time for an effective consultation is provided. But placing maximum limits may also be needed, both to limit the cost associated with consultations for employers and the detrimental effects for workers, who face uncertainty and psychological pressures during these times.

In practice, several consultations are usually necessary, depending on the extent to which the agreement could be reached during the first consultation. The actual length of the consultation process may hence vary within the same country and for various dismissals, and may depend on the complexity of the situation, the number of workers involved, and the type of measures that need to be agreed upon and put in place in order to mitigate the consequences of collective dismissals. Moreover, when notification to public authorities is required by law, public authorities may request additional consultations if they feel that not all options have been explored by employers and workers’ representatives, or that the consultations have not been carried out in good faith.

Box 5. Timing of information and timing of notice: examples of practice

Within the European Union context, the European Union Court of Justice judgment in Junk v Kuhnel (Case C - 188/03) clarified the concept of ‘redundancy’ within the meaning of the Council Directive 98/59/EC and provided a definitive determination of the point in time at which the event constituting redundancy (in a collective redundancy context) occurs. The Court ruled that the consultation process required by the Directive must take place before employees are given notice of dismissal, rather than after individual notices of dismissal have been issued, but before they take effect. In practice, the judgment also meant that many employers started opting out for a payment in lieu of all (or part of) notice, so that the redundancy could take place at the end of the consultation process, not at the end of the notice period following the consultation (NERA, 2016).

In recognition of the important role of information and consultation, it is not uncommon that they are conducted even in those countries where they are not legally required. For example, in Brazil, the jurisprudence “Embraer” became emblematic in 2009. Even if from the legal point of view, the employer was not obliged to consult with the trade unions, a trade union complained to the tribunal about the lack of consultation on collective dismissals, and the tribunal positively accepted the complaint in light of the importance of the dismissal that was to be undertaken. Convention No. 158, although not ratified by Brazil, was mentioned as an international reference. Similar decisions of some regional courts have constituted important precedents, which cannot be ignored by companies considering mass redundancies. Although these decisions were being partly overturned in 2010, the Superior Labour Court of Brazil highlighted the importance of collective bargaining to avoid significant job losses, and some firms continue recurring to the consultation even if they are not legally obliged (Muller, 2017).

Special procedures triggered in case of collective dismissals: Notification to competent authorities

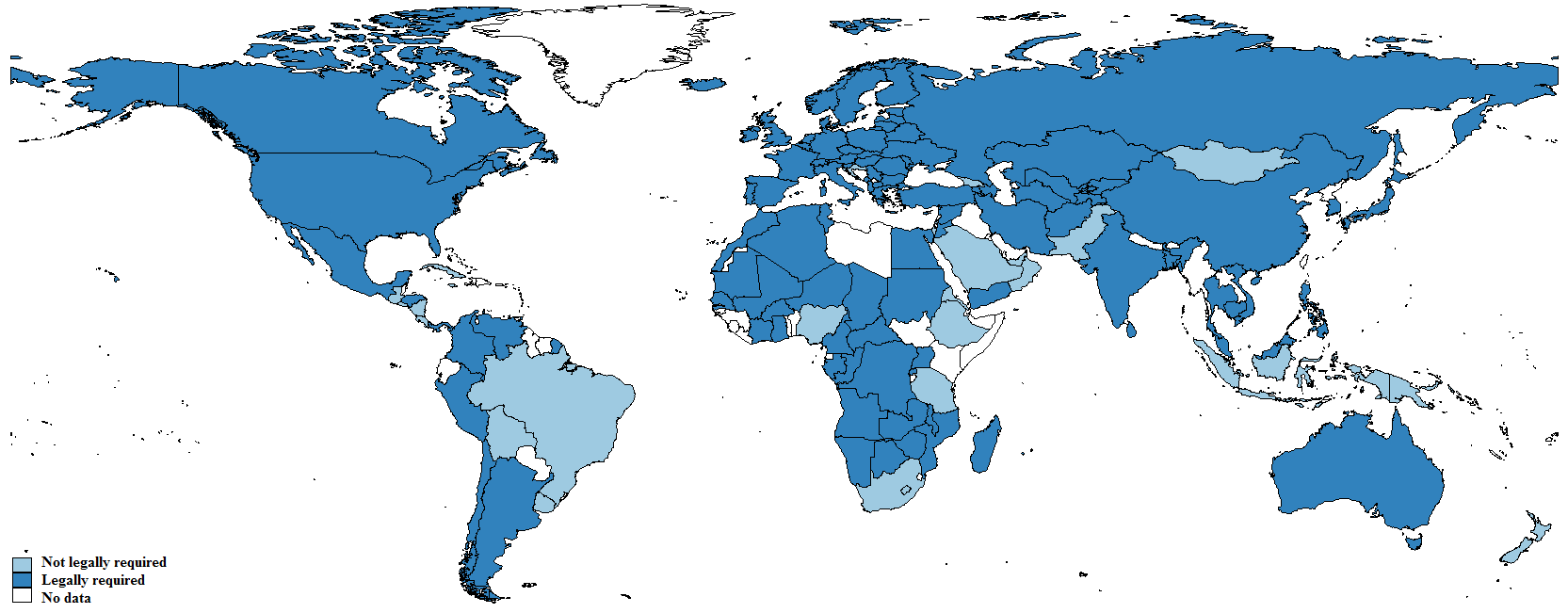

The laws of the majority of countries contain the requirement of notifying competent authorities of terminations that the employer contemplates for reasons of an economic, technological, structural or similar nature. This concerns 101 countries with available information (Figure 4). Competent authorities that are to be notified differ across countries, and most frequently include the Ministry of Labour or Employment, the labour inspectorate, a public employment service, an unemployment insurance or social security fund.

Figure 4. Notification to public authorities: legal requirement

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

Notification to competent authorities may be an alternative measure to the notification of workers’ representatives

Table 2. Examples of countries in which informing public authorities and workers’ representatives are alternative measures

|

|

|

|

The laws require that the employer informs only the competent public authority, but not the workers’ representatives |

Afghanistan, Armenia*, Azerbaijan*, Bangladesh, Botswana, Colombia, Comoros*, Honduras, India*, Kazakhstan*, Malaysia*, Mauritius, Montenegro, Panama, Philippines, Rwanda*, Sri Lanka, Seychelles, Sudan, Thailand*, Uganda*, United States of America, Yemen |

|

The laws require that the employer informs only the workers’ representatives, but not the competent public authority |

Croatia, Ethiopia, Indonesia*, New Zealand*, Nigeria (information though not consultation) South Africa*, United Republic of Tanzania* |

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. For countries marked with *, the same information is still true in 2019. For all other countries, there is no information yet available for 2019.

In contrast, only 22 countries also require that collective dismissals be authorized by public authorities (Figure 5). This is a significant change from some decades ago, when, for instance, many European countries contained such legal requirement (Cosio et al., 2017; EU, 2006). Out of those 22 countries, seven are also the ones in which no information/consultation procedure with workers’ representatives is required: Afghanistan, Colombia, Honduras, India, Panama, Sri Lanka, and Sudan.

Figure 5. Authorization by public authorities: legal requirement

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

The economic and social rationale of notification is to improve risk-sharing and redistribute economic losses among tripartite economic actors. It can allow public authorities to jointly elaborate safeguarding measures helping employers to preserve the sometimes considerable investment represented by the costs of recruiting staff with the right experience, as well as staff’s skills and experience acquired on the job and sometimes through expensive training (GS 1995). It can also prevent the loss of firm-specific human capital. Measures such as work-sharing, reduced hours of work, and restrictions on overtime, allow to rationalize the workforce and to save upon other costs, such as costs of severance payment that need to be paid to terminated workers (ibid, p.118; European Commission, 2009). In many countries, the involvement of public authorities to the joint elaboration of measures mitigating terminations helps ensure that such measures are financed by the State. For example, reductions in the hours of work may not necessarily result in the loss of salary, if state compensation can cover the shortfall; this can be a means to preserve the production capacities of the enterprise at little, or no, additional cost. Some employers may also qualify for wage subsidies for retained or rehired workers.

The

The

From the economic viewpoint, giving the social partners sufficient time to negotiate the dismissals and elaborate social plans is to be weighed against the macroeconomic cost of not doing so, or of negotiating poorly defined social plans. Either could result in mass dismissals and resulting mass unemployment, wider social unrest and adverse political consequences.

Authorization by competent authorities is also part of the timing schedule for collective dismissals, which may sometimes run concurrently with the information and consultation process with workers’ representatives. In case no public authorization is received, the employers may still have an option of triggering a series of individual dismissals, which may take a longer time to complete, and be challenged if a collective dismissals’ procedure is perceived as not respected.

While the laws of many countries contain the legal obligation to inform a competent public authority in case of terminations for economic or similar reasons, it does not mean that the

The role of the competent authorities ranges from monitoring the dismissal process (ex.: UK), to systematically and proactively verifying the substance of dismissals and the extent to which a general interest of the economy is respected (ex.: Greece), to requesting additional consultations when necessary (ex.: the Netherlands), to assisting parties in finding solutions (ex.: Portugal), to carrying out conciliations (ex.: Peru, Tunisia). Competent authorities are often directly and proactively involved in a joint elaboration of social measures to mitigate the effects of terminations (ex.: France).

In some jurisdictions, in consultation with the local employment services and trade unions (or workers’ representatives), public administrations may suspend collective dismissals for a given period, if the labor market situation is particularly unfavorable. Such suspensions may have limits provided by statutory laws. For example, they can last up to 60 days in Cambodia, 6 months in the Russian Federation, 1 year in Belarus, or be without any statutory limit in Venezuela (Muller, 2011).

In countries where the authorization of public authorities is mandated by law, some may only have administrative powers and a purely administrative function of approving collective dismissals as long as the procedures are respected (ex.: India). Others may also to some extent exercise political discretion, which may be manifested in different ways depending on the electoral and economic cycles. Some of those public authorities may have an almost unlimited discretion over authorizations of dismissals, which often has to be exercised within a short period of time before the authorization can be considered as granted automatically (ex: Greece prior to the 2017 reform). In others, if an agreement is reached between the employer and workers, the administrative authorities must authorize collective dismissals. Finally, in some jurisdictions, several public authorities need to intervene.

The roles of public authorities

Once the authorization for terminations is granted by competent authorities, it may nevertheless be still contested or challenged in court. Depending on the jurisdiction, parties may start a litigation procedure or seek resolution from other competent public authorities. The authorization of a public authority may be refused if legal provisions with regard to termination have not been complied with (GS 1995).

Special measures to avert or minimize dismissals for economic reasons and to mitigate their effects

Figure 6 shows countries which do and which do not require, by statutory law, that the employers consider alternative measures before termination of the employment. This legal requirement exists in 70 countries with available information.

Figure 6. Legal provisions requiring the employer to seek alternatives to dismissals

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

The most frequent measures found in national laws or experienced in national practice, among those listed in the ILS, include finding alternative employment, early retirements, and reduction of overtime. Other measures, including work-sharing and temporary part-time, are usually more of a prerogative of collective agreements. In some countries, the absence of consideration of alternative measures to avoid or reduce the number of dismissals can invalidate or nullify the dismissals (ex.: France, Germany). Even if it may not always be possible to apply such alternative measures, some countries considered that they should at least be examined. In economic downturns specifically, governments may put forward specific measures of paying the salaries of those workers who are in “technical unemployment,” or allowing for delays in paying social security contributions and taxes, in order to prevent collective dismissals.

Many of these different measures were used in response to the global economic crisis of 2008-2011, at the company, but also at the regional or state level. Some enterprises, particularly in Germany, but also in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, the Russian Federation, and Indonesia, have prioritized internal flexibility measures over terminations, through policies of work-sharing, also called “short-time work” or “partial unemployment” (see Box 6 for examples). In Germany, work-sharing arrangements had already been part of collective agreements prior to the crisis, and both workers and employers had experience with such measures, facilitating its deployment during the crisis (ILO, 2016). There are also examples of using working time (time-saving) accounts in order to increase flexibility in production to meet the fluctuations in demand and secure employment (ILO, 2011a).

Box 6. Temporary reduction of working hours as an anti-crisis measure

An anti-crisis agreement was adopted in 2010, and featured, among other measures, the introduction of flexible working hours, part-time work for a period not exceeding three months, and unpaid leave for economic reasons. This resulted in substantial growth of reduced hours and part-time work. Some of it was subsidized by the state by “equal to one-half of the minimum salary per month” (Kirov 2010, p. 47). Spill-over effects were also observed in that companies which did not qualify for state subsidies also reduced working time and put numerous employees on paid or unpaid leaves.

In 2009, two large automotive companies introduced four-day work weeks for all regular employees. The lost day was compensated at 75 per cent of the usual salary.

In 2010, the social partners in the metal industry launched a time-limited ‘Future in Work’ agreement (Zukunft in Arbeit, ZiA). The agreement was destined to companies that already experimented with and exhausted work-sharing. It allowed prolonging time-sharing schemes for 6 months, and allowed further reduction of working hours provided a partial compensation was paid. Depending on the region, weekly working time could be reduced to 29 hours (Eastern Germany), or 26 to 28 hours (Western Germany). “A reduction to 28 hours is enforceable through an arbitration committee; a reduction to 26 hours is to be settled through a works agreement. Any reduction below 31 hours is to be compensated. In the case of 28 weekly working hours, 29.5 hours are to be paid, in case of 26 hours, it is a wage-equivalent of two extra hours” (Stettes 2012).

Several medium-sized companies, such as Estiko Plastar, set a substantial proportion of employees to part-time work, without cutting wages accordingly, through installing other measures, such as abandoning the usual paid Christmas holiday, or institutionalizing work on weekends in order to meet fluctuations in demand (Masso and Krillo 2011, p. 75).

Labour Code of the Russian Federation allows for an involuntary working time reduction for a period not exceeding 6 months. During the crisis, numerous enterprises thus adopted this measure, resulting in about 20 per cent of the country’s workforce reducing their hours or taking involuntary or quasi-voluntary leave (Gimpelson and Kapeliushnikov 2011, p. 11).

Tambunan (2011) analyses crisis-adjustment strategies adopted by SMEs in the Indonesian furniture industry through a random study of 39 SMEs. Employers were asked about the labour adjustment measures adopted since 2008. Reduction of working time was adopted by 38 per cent of firms, with all or most of the working-time related adjustments entailing cuts in wages. However, women, temporary and unskilled production workers were the first affected by these measures. As this industry in Indonesia is male-dominated, and women perform periphery unskilled tasks; in times of lower demand they are often terminated and their work is given to male skilled staff who perform those periphery tasks in addition to their main tasks.

Source: Based on Kummerling and Lehndorff, 2014; and ILO, 2016

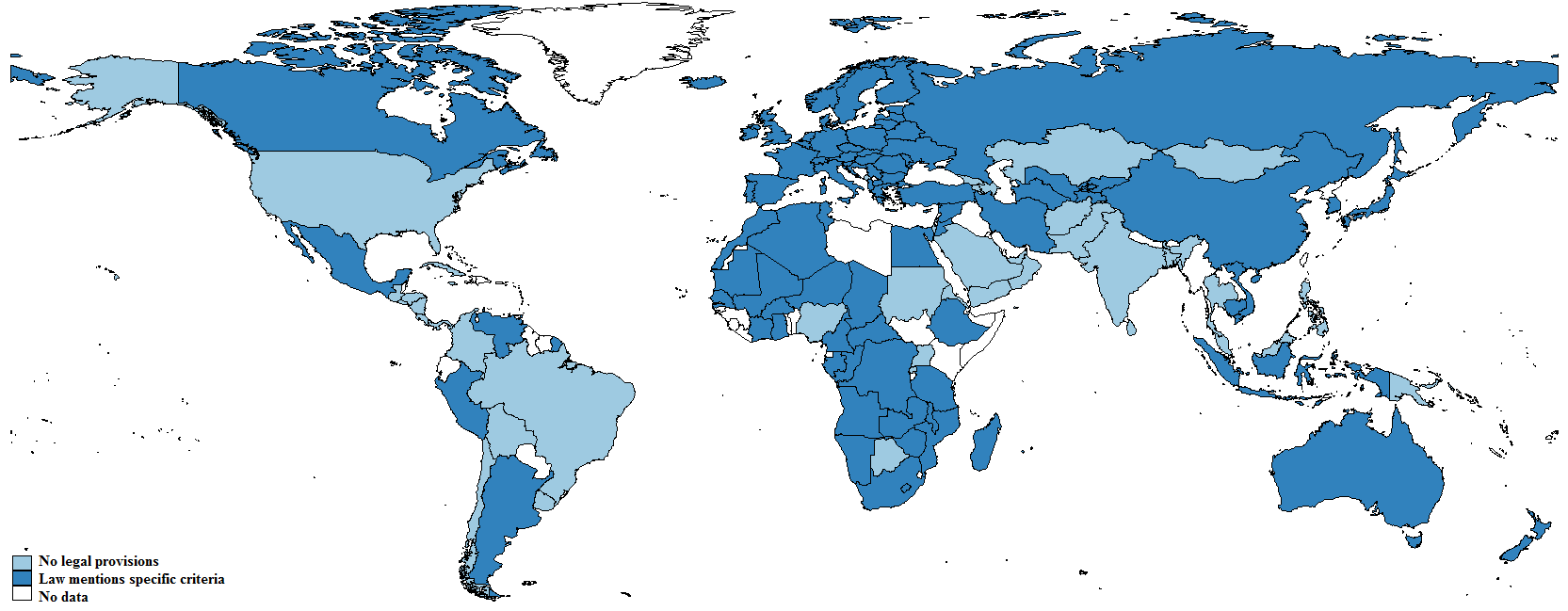

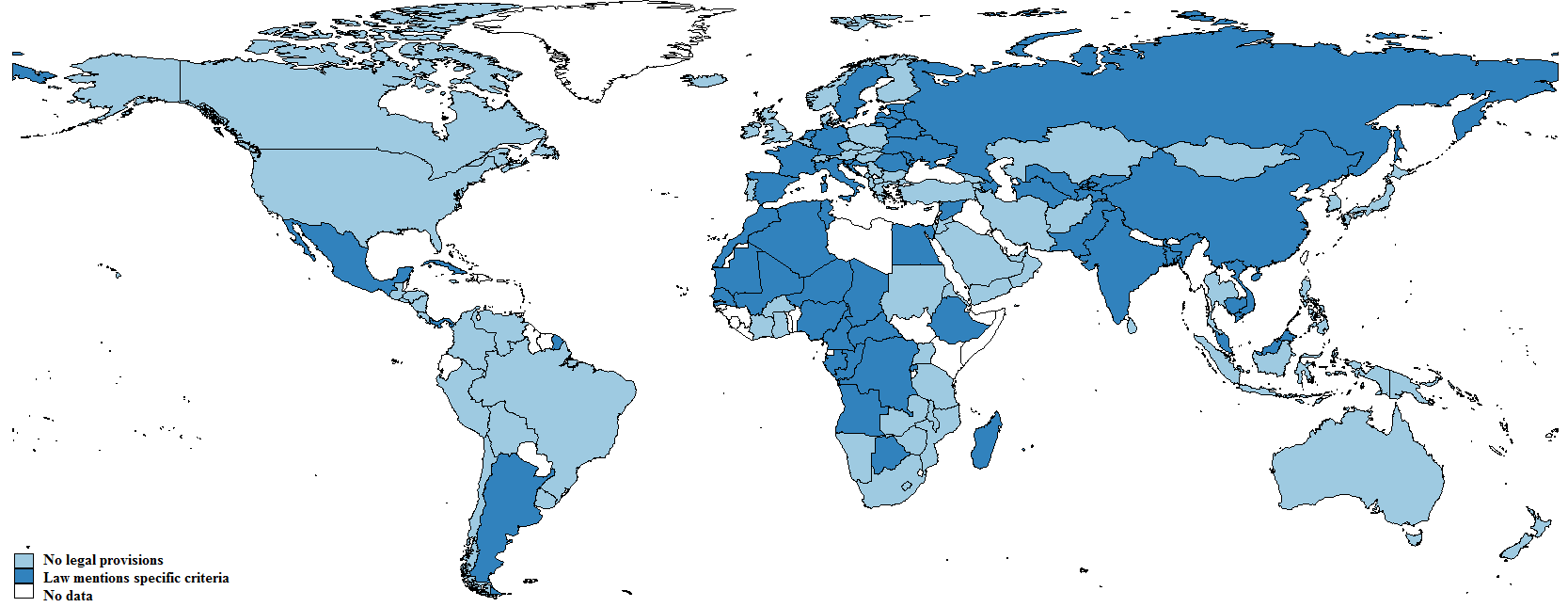

Regarding specific criteria for selection of employees to be dismissed, 54 out of 132 countries (of which 110 have special provisions) contain specific criteria for selection of employees (Figure 7). Most frequently used criteria include skills, productivity, and social considerations. In some cases, laws may contain detailed additional criteria, such as length of service and rank class (ex.: Portugal), disability (ex.: Central African Republic) or difficult re-entry into the labour market, such as in case of elderly employees (ex.: France).

The laws may also state that specific selection criteria are to be established through collective bargaining. Indeed, the establishment of selection criteria is one of the areas that is historically subject to regulation through collective agreements and codes of good practice. Discussion of selection criteria may also be part of the consultation process.

Figure 7. Criteria for selection of workers whose employment is to be terminated for reasons of an economic, technological, structural or similar nature

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

Recently, some countries underwent re-examination of which criteria can be used to establish priority rules for termination. In some (ex.: Romania), social considerations were removed from the list of criteria established by the law, as they could be seen as indirect discrimination. In case of redundancy processes, discrimination is most frequently claimed on sex and age grounds. In the United Kingdom, the Employment Tribunal decided in 2011 that "special treatment" for women in connection with pregnancy or childbirth must be reasonable and proportionate and found that a redundancy scoring exercise constituted sex discrimination against a man in the redundancy selection pool (Eversheds Legal Services Ltd v de Belin [2011] IRLR 448 EAT). In Slovenia, specific rules are to be respected in case of terminating, including for economic reasons, the employment relationship of a person with disabilities (Blaha, 2017). In addition, countries are progressively abandoning the last-in-first-out system, whereby the worker with lowest tenure is terminated first; this is because such principle may also be seen as indirect discrimination on the grounds of age.

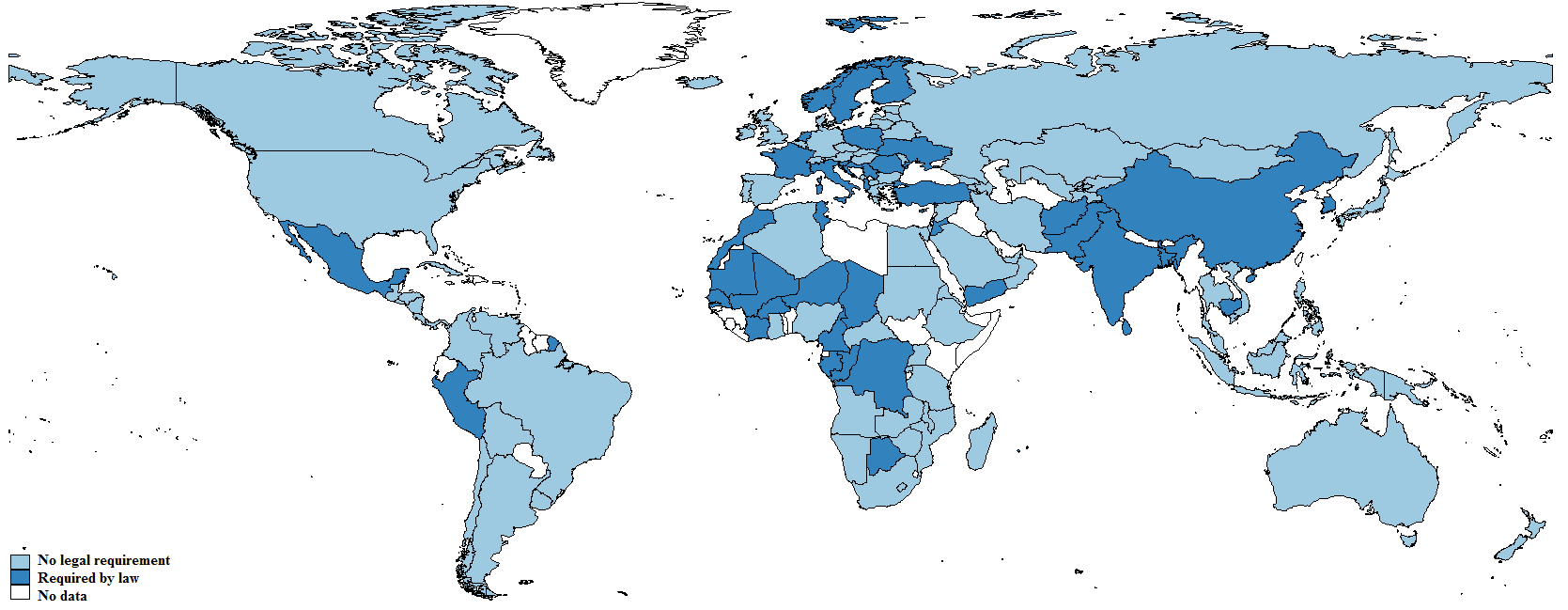

The principle of priority of rehiring is retained in law in forty-three countries (Figure 8). Only about a half of them have explicit time thresholds during which giving priority to rehiring of dismissed workers is required in law. They range from 1,5 months in Romania to 3 years in the Republic of Korea, with the majority of these countries having a one-year limit (Table 3). In addition, some countries contain provisions forbidding to recreate a suppressed post within a specified time limit (ex.: Moldova; Slovakia). It is also often illegal to replace workers made redundant through a collective dismissals procedure by temporary agency workers.

Figure 8. Priority of rehiring as mandated by law

Source: ILO EPLex and Muller (2011). Information as of 2010. See also Annex 1.

Table 3. Priority of rehiring: variations in legal limits when the principle is applied

|

|

|

|

1.5 months |

Romania |

|

6 months |

China, the Netherlands, Serbia, Turkey |

|

8 months |

Cyprus |

|

9 months |

Finland, Sweden |

|

1 year |

Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of the Congo, France, Gabon, Italy, Jordan, Luxembourg, Morocco, Pakistan, Peru, Slovenia, Tunisia, Ukraine |

|

2 years |

Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Comoros, Niger, Senegal |

|

3 years |

Republic of Korea |

|

No time limit |

Afghanistan, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Yemen |

|

The law makes express reference to collective agreements |

Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar |

|

The right is embodied in the code of good practices |

Lesotho, Malaysia, Tanzania |

Source: Muller (2011), with adaptations. Information as of 2010.

Final assessment

This paper provided comparative data on regulations of collective dismissals worldwide, and presented the economic and social considerations which underpin these legal frameworks. Given the high level of both academic and policy debate concerning the “flexibility” or “rigidity” of EPL, such a twofold approach, combining law and economics, can hopefully contribute to the analytical work on improving the operation of the labour markets. This double reflection also provides some guidance on the need to keep in mind the fundamental objectives of EPL.

As can be seen by the discussion, there is a diversity of legal regimes and practices concerning collective dismissals. ILS are reflected in national regulations and also provide guidance for those countries that transpose their provisions into their national frameworks. The vast majority of countries recognize the market-correcting aspects of collective dismissals provisions, by providing general provisions that explicitly reflect the economic thinking. For example, having quantitative definitions allows public authorities to better prepare for the labour market and budgetary consequences, and facilitates the use of public funds for mitigating the negative consequences of collective terminations.16

These similarities across countries, however, hinder important differences in the understanding, interpretation and implementation of seemingly similar provisions. Moreover, the value of seemingly similar provisions may vary not only across countries, but also within the same country, depending on a specific dismissal plan, geographical area, sector of activity, the content of the negotiated social measures and the power of tripartite social partners in a particular point of an economic and political cycle.

There are also asymmetric implications of these provisions for workers, employers, and societies, in the sense that more worker protection implied by some regulations does not necessarily create symmetric costs to the employer. Rather, all labour market actors may find value in these provisions. The spirit of the regulations to be implemented “without prejudice to the efficient operation of the undertaking, establishment or service” (R 166, Para. 19) is often intended to help the enterprise to survive through the hardships while also helping workers to avoid terminations or mitigate their negative effects. For a social planner, the value of such measures is substantially broader, as they allow preventing unemployment and deskilling, maintain workers employability and enterprises viability.

Given this, the scope for effective comparisons of collective dismissals’ provisions across countries, without recognizing their benefits for employers and for the societies at large, may be limited. Any general cross-country assessment of EPL should strive to take into account various economic channels through which the effects of legal provisions propagate, and also the implications of alternative counterfactuals. The paper does not, however, imply, that comparative cross-country research in this area should not be undertaken. On the contrary, it highlights the benefits of interdisciplinary research as a promising path to combine and better understand the legal, social and economic implications of EPL.

Yet, going from the cross-country comparison of provisions to a meaningful assessment of whether these provisions actually do reach the goals of effectively correcting market failures is not easy. This is because some further caveats also need to be considered, and those relate, but are not limited to: (i) difficulty to establish equivalence of seemingly similar provisions across countries; (ii) availability of a wide range of dismissal options; (iii) particularly important role of collective agreements; (iv) articulation of employment termination regimes with other policies; (v) issues of coverage and enforcement of these statutory provisions. We consider these in turn:

(i)