Youth Aspirations and the Future of Work

A Review of the Literature and Evidence

Introduction

Poverty, despair and precariousness are commonly understood to deprive young people of significant opportunities, experiences and even freedom. The effects of poverty can extend beyond economic opportunities and deprive young people of their aspirations and leave psychological scars. And especially in the context of the massive current and future changes in labour markets around the world, a vitally important question is whether it is possible to enhance the beliefs and aspirations of young people – even those most economically marginalized – in a way that helps them overcome what life throws in their path? The answer is that, if it is possible to influence beliefs and aspirations in such a way as to lead to higher levels of labour market attainment, then appropriate policies can be developed.

As confirmed by recent trends analysis, young people in particular remain disadvantaged in the labour market. The transition from school to work is increasingly difficult, with the latest data putting the global youth unemployment rate at 13.6 per cent in 2020. Three out of four young workers are employed in the informal economy, especially in the developing parts of the world. Informal employment is one of the main factors behind a high incidence of working poverty among young people. According to International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates, more than a fifth of young people are not in employment, education or training, three-quarters of whom are women.

Compounding this situation is the fact that the world of work is changing rapidly, with technological and climate change altering the conditions of production and labour markets undergoing substantial shifts. The transformation of employment relations, expanding inequalities and economic stagnation greatly hamper the achievement of full employment and decent work for everyone.

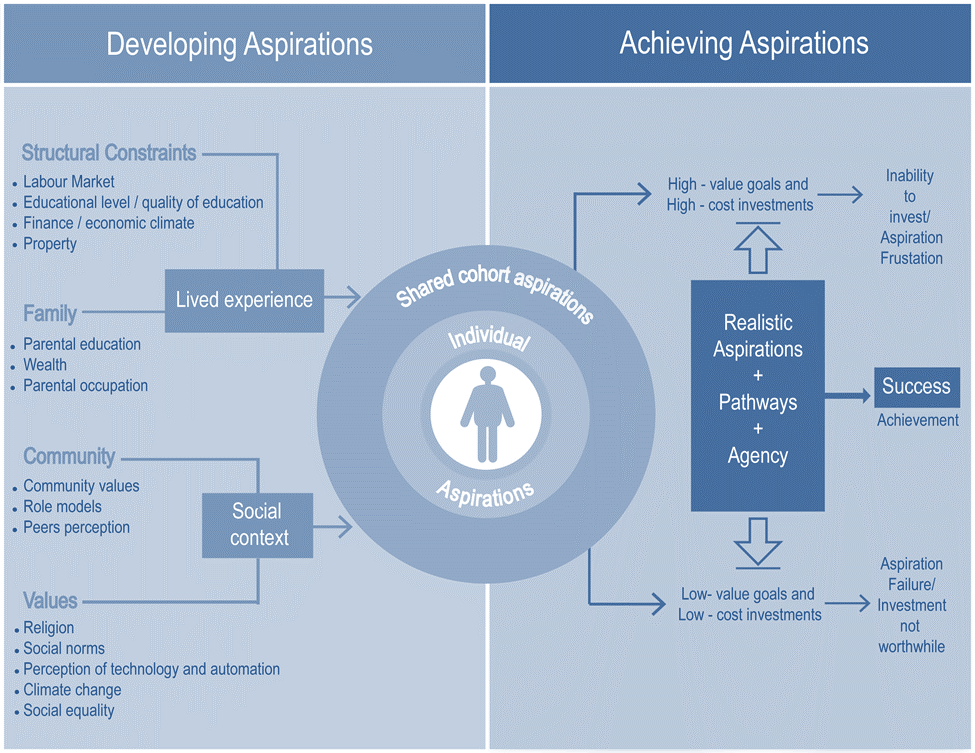

If young people are to benefit from the changing nature of the world of work, they need to be prepared, both in terms of skills attainment and level of ambition and aspiration. The aspirations of young people are essential to their human capital investment, educational choices and labour market outcomes. When realistic aspirations combine with an individual’s sense of agency and a belief that change can occur through their own effort, and given the pathways and tools to support achievement, success can be the outcome.

Understanding aspirations is important when developing effective employment policies. If the career aspirations and life goals of youth are not considered, employment policies aiming to “match” skills with labour market opportunities may continue to fail young people.

This report was undertaken as part of the ILO Future of Work project and aims to (i) review the literature on the concepts and drivers of aspirations; (ii) develop a conceptual framework that relates labour market conditions to aspirations; (iii) map the existing survey-based evidence on the aspirations of youth worldwide; and (iv) provide insights into how to improve data collection, research and evidence-based policy-making related to young persons aspirations.

In particular, the objectives of this report are to:

-

review the literature discussing the concepts of aspirations, beliefs, expectations, and the relations between them;

-

understand the drivers and determinants of youth aspirations;

-

provide a conceptual framework on how labour market policies and shocks affect aspirations;

-

identify existing data sets and survey questions measuring aspirations and related concepts in the world of work;

-

identify gaps in the evidence and provide recommendations for future aspirations data collection;

-

formulate recommendations for aspirations-sensitive employment policies.

This review is structured as follows: section 2 provides information on the methodologies used to identify and select the relevant literature and data sources. Section 3 develops a theoretical framework based on scientific studies into the concept and determinants of aspiration. Section 4 turns to the world of work and highlights the current important challenges impacting youth aspirations worldwide. After presenting an overview of the survey-based data sources covering youth career aspirations and related concepts in section 5, section 6 presents key evidence of aspirations, mapping the global trends in youth aspirations as labour markets change. Section 7 concludes with recommendations for data collection and for the development of interventions that take account of aspirations in order to produce better labour market outcomes.

This work was undertaken by a group of researchers at UNU-MERIT, Maastricht, the Netherlands, coordinated by Micheline Goedhuys of UNU-MERIT and Drew Gardiner of the ILO. The researchers and co-authors to this report include Alison Cathles, Chen Gong, Michelle González Amador and Eleonora Nillesen. The research took place from 25 November 2018, until 30 April 2019. The review was presented at ILO Geneva, on 19 April 2019, Employment Seminar Series #26 on “Aspirations and the Future of Work: Global Evidence”.

Methodology of the study

The sections into which this review is divided each has its own scope and objectives and therefore different search techniques were applied to identify the most relevant literature. To develop the concept of aspirations, in section 2, we first look at early academic discussion of aspirations and the economy, and then expand on its conceptualization by revisiting classic papers in Psychology and its application in current literature on Behavioural Economics. We further divide section 2 into subsections to facilitate an easy flow of ideas, from (a) the concept of aspirations (how they differ from beliefs and expectations, how they might be biased and how they might fail); to (b) what shapes and drives aspirations (poverty, policy shocks, role models, community structures and peers’ networks); and finally to (c) the effectiveness of aspirations (results from empirical studies on aspirations and policy implications).

The papers used in this review were identified through a systematic search using Google and Google Scholar; EBSCO (EconLit); SpringerLink; Maastricht University Library; and Elsevier for the period 1998 to 2018, as well as revisiting some classics from 1966, 1977 and 1981. The keywords used to identify the relevant papers included, but were not limited to: aspirations, aspirations formation, aspirational failure, aspirational bias, adolescents’ aspirations, aspirations and educational outcomes, aspirations and labour market outcomes, occupational outcomes and choices, drivers of aspirations, role models, social interactions and aspirations, hope and aspirations, capacity to aspire, aspirations and economic change.

For section 4, which addresses challenges in the labour market, we build on the existing reports published by the International Labour Office, such as the

To map aspirations and the labour market outcomes for youth (sections 5 and 6), an initial list of surveys was provided by the ILO. This was then expanded in the following ways. If a report from the initial list mentioned another survey or report containing data from focus groups or interviews, it was checked and, if found to be relevant, added to the list of literature. A few other sources were identified through a systematic search in Google, Google Scholar, the Maastricht University Library (which houses numerous databases and e-journals) and the websites of the following international organizations whose data is open to the public: Eurostat, the ILO, the OECD, UNESCO and the World Bank. The following keywords were used: “survey”, “data”, “interview”, “focus group” plus “youth aspiration” and variants, such as “young people”. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) was not found via this search, but instead added because of potential indicators of interest.

We first searched the databases looking for (i) type of indicators; (ii) accessibility of indicators at country level or in a more disaggregated form, either as data or from reports; (iii) country coverage; (iv) years covered; (v) representativeness of the underlying sample; and (vi) target group. Based on this outcome, we extracted countries (including emerging ones, such as the BRICS countries, developed and developing countries) and indicators (related to perceptions, aspirations and expectations, and drivers regarding technological change, employment and education) in order to identify data trends across different geographical regions.

The concept and determinants of aspirations

3.1 Understanding aspirations

Aspirations are the driver of an individual’s life path and well-being. The idea that aspirations are proxies for human choice and determinants of socioeconomic outcomes is not new to the social sciences. Ever since the landmark examination of aspirations in Kurt Lewin’s

Appadurai and Ray posited the notion that aspirations are unevenly distributed across society and that people born into poverty, among other structural disadvantages, are less likely to aspire to make significant changes in their lives. This results in low human capital investment and hinders the social mobility efforts that policy tries to promote. Appadurai (2004) defines aspirations as a “capability”; that is, the capacity to aspire is the ability to navigate social life and align wants, preferences, choices and calculations with the circumstances into which a person is born. However, as a navigational ability, the capacity to aspire is not distributed evenly: individuals born into less privileged backgrounds will have a more limited social frame within which to explore what is possible than their more privileged counterparts.

Ray (2006) has contributed to an understanding of the capacity to aspire by introducing the concept of “aspirations failure”. For Ray, the capacity to aspire can be measured as the distance between where you are and where you want to go. How great this distance is, the extent of the “aspiration gap”, determines whether aspirations can be a true motivator of change during the life course or whether there is instead a likelihood of aspirations failure through a lack of capacity to aspire. If the gap is too small, then a person will fail to aspire to significant change in their life; conversely, if the gap is too large, a person will fail to turn aspirations into action. Moreover, setting unrealistic aspirations might decrease the motivation to see them fulfilled. Thus, the relationship between aspiration and action is shaped like an inverted U: aspirations that are either too low or too high will yield limited action, whereas reasonable aspirations will motivate effort and produce action.

Dalton, Ghosal and Mani (2016) explained this phenomenon further by introducing aspirations failure as a “behavioural bias”, something to which all people, regardless of background, can be susceptible. In their view, individuals can fail to recognize the adaptive, dynamic mechanism in operation between effort exerted and aspirations. Aspirations spur effort and motivate action, but the level of effort a person chooses to exert will influence their future aspirations through realized outcomes. This dynamic has an especially detrimental effect on individuals confronted with a tremendous number of external constraints; for instance, only limited or non-existent material resources. Because poverty is the biggest external constraints, people who are poor must exert greater effort to achieve the same result as those who are not poor. Failing to account for this susceptibility in the design of socioeconomic development policies can result in a low take-up of opportunities or their being missed entirely.

Acknowledging the relevance of aspirations to development efforts, Lybbert and Wydick (2018) investigated how aspirations can be realized and become positive outcomes. They turned to Snyder’s (2002) theory of hope1 to explain how to arrive at successful aspirations. First, individuals need to set a goal for the future (an aspired position). Second, they need to have the necessary agency to carry out the steps required to attain that goal. Third, they need to visualize pathways to achieving that goal, such as access to the cognitive or material tools necessary for their journey.

When what a person aspires to for the future is aligned with what they believe can be achieved, given their circumstances and through their own effort (Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2016; Bandura, 1993), then aspirations become analogous to expectations and successful outcomes more likely. Therefore, whereas aspirations afford a dimension for preferences, expectations are the product of experiential perceptions, such that they become more context specific. Through this framework, the inverse U-shaped relationship between aspirations and action propounded by Ray can be better understood as the proposition: if aspirations that are either too low or too high discourage motivation, then there is a peak to be found where aspirations meet expectations towards the top of the inverse U curve. By designing policies and programmes that help recipients visualize the potential pathways to achieving their goals, development efforts can productively mobilize the motivating power of aspirations.

In line with Appadurai’s notion that the capacity to aspire is defined by social frames, Bandura (1977) had earlier investigated how social experiences shape how we behave in society. Social learning, either by the setting of personal boundaries through social norms or by imitating role models, determines how we behave and what we believe to be attainable for ourselves. Bandura introduced another component of cognitive and social learning, namely, “self-efficacy”, or, the belief in one’s capacity to succeed in any given situation. Self-efficacy is shaped by personal experiences and an important driver of aspirations (Bandura et al., 2003).

Bandura’s ground-breaking study of the capacity to aspire finds an echo in Amartya Sen’s “capability approach”. Sen (1985) proposed a framework in which human development is centred on an individual’s person’s capabilities and the real opportunities presented to that individual to do what they have reason to value (Robeyns, 2016). Not unlike Appadurai’s and Ray’s conceptions of aspiration formation, Sen posited that opportunities are not solely dependent on an individual’s choices but also on their social circumstances (Drèze and Sen, 2002). However, Sen conceived social circumstance as being what a society could provide for its citizens in terms of structures, as opposed to the cognitive roadmap envisioned by Appadurai and Ray. Together, they provide a larger picture of the phenomenon: an individual’s capacity to aspire to, say, productive work, is contingent upon their own experiences (Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2016), what they learn from society and what society can provide for them. The latter two are of particular interest for policy, because they mean that work aspirations are shaped by a person’s experience with, assessment of and expectations about the labour market institutions and policies operative in their society.

Aspirations require further investigation, because they tell us about the well-being of individuals and something about the cooperative nature of the recipients of development policies and social programmes. If people believe they have the ability to bring about meaningful change in their lives through effort (Lybbert and Wydick, 2018; Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2015; Bandura, 1993), and that they have the necessary avenues and pathways to change, be it naturally through social circumstances (Ray, 2006; Appadurai, 2004; Bandura, 1977) or by design through policy (Lybbert and Wydick, 2018), then they are likely to accept the opportunities offered to them through policy interventions.

3.2 What shapes aspirations?

The empirical literature defines aspirations as forward-looking behaviour. Aspirations capture the personal desires of individuals (preferences and goals), their beliefs about the opportunities available to them in society (opportunities and pathways) and their expectations about what can be achieved through their own effort in an uncertain future (self-efficacy and agency)2 (Favara, 2017; Ross, 2016; Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2016; Bernard et al., 2014; Bernard and Taffesse, 2014; Bernard et al., 2011). This working definition has allowed policy and development researchers to disentangle the mechanisms by which the circumstances in which we live affect aspirations formation and the extent to which an updating of aspirations results in improved outcomes.

Through the frameworks developed by Appadurai (2004) and Ray (2006), aspirations are understood as being socially determined: our perception of what is available to us in society is greatly influenced by what others around us think and do. The behaviour of our immediate social network is a reference that informs our own behaviour (Bogliacino and Ortoleva, 2013). For example, in a review of risk preferences and social interactions, Trautmann and Vieider (2012) demonstrated that risk-taking behaviour changes together with aspirations when subjects are placed into peer groups where they suddenly find themselves at risk of losing what they have. Peer frame, or peer structure, is perceived by subjects as a social reference point, which changes aspirations and, consequently, risk-taking behaviour and actions. Similarly, studying a sample of Chinese workers, Knight and Gunatilaka (2012) observed their income aspirations evolve positively over time together with those of their peer frame. Favara (2017) was able to show that the aspirations of children and adolescents mirror those of their parents and that these are revised over time to adapt to social expectations.

Likewise, exposure to people outside of our immediate social network can have a positive impact on aspiration formation. With reference to Bandura, Bernard et al. (2014) discussed the relevance of role models in the formation of an individual’s perception of what is feasible in their environment; for instance, through the construction of mental models and choice sets. Role models have to be people with whom we can identify socially and whose stories produce a vicarious experience that generates emotions strong enough to spur a willingness in us to change our status quo. By providing new information about what can be achieved in the circumstances we find ourselves, role models update our beliefs and change aspirations and motivations for the better (Lybbert and Wyddick, 2018; Bernard et al., 2014; Beaman et al., 2012; Chiapa, Garrido and Prina, 2012; Nguyen, 2008; Bandura, 1977).

Bernard et al. (2014) and Riley (2018) both tested the effect produced by the exposure of adults and secondary school children to relatable role models and found a relationship wherein they positively affect behaviour. For Bernard et al., adults change how they allocate time in response to aspirational changes; for example, less leisure time means more time at work and increased investment in the education of children. In Riley’s study, Ugandan secondary school children performed better in a mathematics exam after exposure to positive role models.

If new information about what can be achieved in the system in which we live is important, so too is our perception of that system. The study by O’Higgins and Stimolo (2015) provides an example. Using two-shot trust games with random, anonymous matching, they were able to demonstrate that trust is lowest when confronted by unemployment or precariousness and that it varies across job market structures. Bernard et al. (2014) found the same phenomenon, namely, a large proportion of poor, rural households in Ethiopia exhibited signs of holding fatalistic beliefs and having low aspirations and low self-efficacy. Poverty, precariousness and other strenuous circumstances and their opposite, relative richness and safe environments in which to live (Knight and Gunatilaka, 2012; Stutzer, 2004), certainly affect the type of future-oriented behaviour we choose, through the impact they have on our perception of the choices available to us and our ability to contest or alter the circumstances in which we find ourselves (Favara, 2017; Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2016; Appadurai, 2004).

Schoon and Parsons (2002) demonstrated this by looking at the effect the relevance of educational credentials had on two different cohorts’ aspirations and adult occupational outcomes. They found that when the socio-historical context makes academic credentials more relevant for employment, the younger generation raises its academic aspirations and consequently has better occupational outcomes. Echoing these results, Lowe and Krahn (2000) compared two Canadian youth cohorts and found that occupational aspirations increased in the later cohort to match the opportunities presented by trends in the country’s service-based economy.

Finally, some studies suggest that early interventions are desirable for raising expectations and aspirations. Gorard, See and Davies (2012) documented a series of studies looking at aspirations and expectations, stability over time and effect on educational outcomes. For example, Goodman et al. (2011) found that expectations reported at age 14 were the best predictor of the score gap between low- and high-income students and therefore encouraged policy-makers and education workers to start raising students’ aspirations as early as primary school level. Lin et al. (2009) found that expectations reported in grade seven (approximately age 12) were positively correlated with academic progress in grade eleven. In the same vein, Beal and Crocket (2010) and Liu (2009) observed self-reported aspirations from grade seven to nine and from grade ten until the end of high school and found they remained mostly stable and were reliable predictors of educational outcome. However, knowing that aspirations appear to be formed during early adolescence does not preclude programmes from targeting older youth cohorts. On the contrary, this finding suggests that aspirations are constant motivators in life and should be approached early and continue to be engaged throughout the life course.

3.3 The malleability of aspirations through policy interventions

As our understanding of aspirations in the context of policy and development improves, we see research gradually turn from aspiration formation to how to increase aspirations. Natural and field experiments centred on the concept of aspirations and the individual’s ability to imagine a brighter future for themselves have important implications for policy. Mainly, they demonstrate that the success of policy efforts can be partially secured by engaging the people who they directly affect.

Perhaps the most famous natural experiment on the topic, undertaken by Beaman et al. (2012), used a gender quota policy in West Bengal to illustrate how exposure to positive role models raises educational and career aspirations and improves outcomes for young girls. In 1998, state policy-makers introduced a gender quota for village councils. Some villages were asked to reserve at least one seat for women, some at least two seats; other villages were asked not to reserve any seats at all. Thanks to this design, Beaman et al. were able to study what happened to the cohorts of girls exposed to councilwomen in their villages compared to those who were not. From the time of implementation in 1998 until the first round of data collection in 2007, they observed that exposure to women role models increased primarily the occupational aspirations of the adolescent girls and their parents, with fewer parents wanting their girls to be housewives, and improved educational outcomes.

Both Chiapa et al. (2012) and García, Harker and Cuartas (2016) designed field experiments in which they combined a social programme with exposure to career role models and social leaders. Chiapa and co-authors observed what effect a Mexican conditional cash transfer programme, PROGRESA, had on educational outcomes. They were able to demonstrate that PROGRESA, as a social programme, raised the aspirations of parents for their children for at least one-third of a school year. When comparing persons who had received the cash transfer and were exposed to health-care professionals, Chiapa and co-authors found that educational aspirations extended for half a school year longer than it did among those parents who had received the cash transfer but were not exposed to role models. They also found a positive correlation between parental aspirations and students’ educational attainment (Favara, 2017; Chiapa, Garrido and Prina, 2012).

García, Harker and Cuartas (2016) observed the effect a conditional cash transfer programme, Familias en Acción, had on the educational aspirations of parents and adolescents. They found that the improvement in educational outcomes after the transfer can be partly explained by the increase in aspirations achieved through the exposure of beneficiary parents to social leaders and professionals who shared with them information about local returns to education and the other benefits of schooling. Glewwe, Ross and Wydick (2015) also found that combining a mechanism that relaxes financial constraints with exposure to role models enhances both aspirations and educational attainment rates. Through a child sponsorship programme, they showed that a role model’s impact is greatest in the early stage of exposure. Similarly, Wydick, Glewwe and Rutledge (2013, 2017) found that a child sponsorship programme not only increases participants’ educational attainment, but also enhances their labour market outcomes, measured as the probability of obtaining while-collar employment in adulthood.

In another natural experiment, Kosec and Hyunjung Mo (2017) documented what happens to aspirations when confronted by a natural disaster (i.e. extreme rainfall). As expected, natural disasters have the effect of abruptly changing the perception of safety in the environment and lower aspirations. However, they also found that government social protection programmes can blunt the negative social effect of natural catastrophes. Their study is evidence of the crucial role the state has to play in first shaping and then maintaining a positive outlook on our environment and the circumstances in which we find ourselves.

Another is the study by Ross (2016) of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) programme in India. Initiated in 2006, the NREGA programme guarantees poor households one hundred days of salaried, low-skill employment in any financial year, should they want it. The stability this provides raised the aspirations of parents and adolescents and is associated with higher educational attainment and an increased probability of being employed full time.

Bernard et al. (2014) and Macours and Vakis (2014) designed experiments to observe the effects (i.e. social network effects) peers have on aspirations and outcomes. The one carried out by Bernard et al. (2014) focused on enhancing the aspirations of microcredit borrowers through exposure to role models via a video documentary. This was shown to enhance both the level of aspirations and actual, future-oriented behaviour (such as saving, and time spent on leisure and work). Interestingly, they found that positive peer dynamics (peers included friends, spouses, and so on) further boosted the positive effect of the video. In their turn, Macours and Vakis (2014) chose to observe the effect of social interactions on aspirations by randomly assigning leaders and beneficiaries to lending groups in a microcredit scheme. They found that positive peer dynamics, promoted by more optimistic group leaders, promoted a positive outlook on the future and the probability of on-time repayment.

Judging from the insights generated by the natural and field experiments described, there seems to be a consensus that it is possible to manipulate the conditions under which aspirations are shaped and that the aspirations of individuals matter equally as much for successful policy and social programmes as they do for life outcomes.3 When policies assist in aligning individuals’ educational and work aspirations with the pathways to achieving them, they are more likely to be successful than when such aspirations are ignored. For example, programmes that provide experiential information on how to integrate into the labour market plus a financial aid scheme are more likely to elicit a positive response from the target population than programmes that do not. Programmes tend to miss their mark when they fail to acknowledge that resource scarcity is sometimes more than just financial but can also be a lack of the type of social experiences that help recipients visualize the ways in which financial resources can be put to good use. Labour market policies thus benefit from a holistic design; one that includes role models (who generate vicarious experiences) in combination with skills development and other career supporting interventions (e.g. financing schemes).

Based on insights from the literature and building on the conceptual framework developed by Boateng and Löwe (2018),

Figure 3.1: Developing and achieving aspirations

Labour market challenges and youth aspirations

Career aspirations typically drive individuals’ educational and occupational choices (Duncan et al., 1968; Ohlendorf and Kuvlesky, 1968; Kuvlesky and Bealer, 1967) and vice versa. Career aspirations are influenced by the immediate social context through the own or vicarious experiences acquired from peers, parents and successful role models (Bernard et al., 2014; Bogliacino and Ortoleva, 2013; Bandura, 1977).

In addition to financial remuneration, people aspire to various non-monetary elements related to work, including a healthy work–life balance, social protection, career development and flexibility. Labour market conditions and labour market trends can affect each of these components.

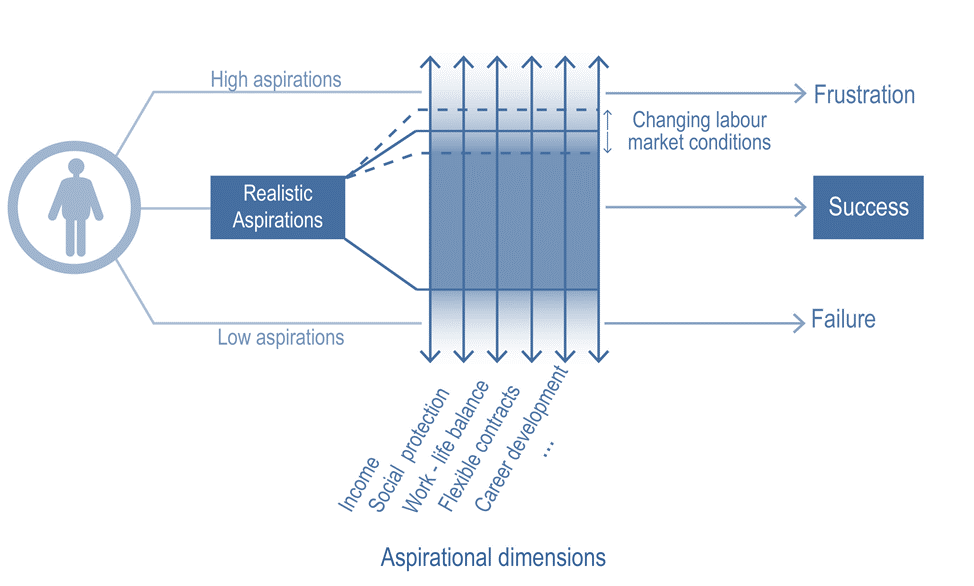

4.1 Labour markets and aspirations: conceptual framework

Career aspirations are influenced by the immediate social context, through own experiences or vicarious experiences acquired from peers, parents and successful role models (Bernard et al; 2014; Bogliacino and Ortoleva, 2013; Bandura, 1977).

4.1.1 Dimensions of occupational aspirations

Given the many differences in experiences, in availability of role models and in social norms and (local) labour markets, aspirations necessarily differ considerably across and within regions and countries (across rural and urban settings), and even between individuals across the different stages in life. Boateng and Löwe (2018) have described how in rural communities in Ghana, where the cocoa crop is regarded as the pride of the country, cocoa farmers are the most highly respected professionals, whereas in urban areas, respect is reserved exclusively for office workers and white-collar professionals. They also showed how aspirations change over the life course. They noted that most young people earn a living from doing ad hoc jobs: “The priority for most young people is to make ends meet and to be seen to be contributing to their immediate and extended families’ well-being and upkeep. In other words, the earning potential of various tasks and jobs was the key consideration for most young people.” This enables them to build up some savings in the medium term in order to raise a family. But for the longer term, they aspired to jobs that are less physically demanding, once passed middle age (Boateng and Löwe, 2018).

This example demonstrates that what people value about a job, and what they may realistically aspire to in the short, medium and long term, has many dimensions. An important one – if not the most important – is the financial remuneration for the work undertaken. Earning a decent income is what enables young people to develop aspirations for the longer term, such as raising a family, building up emergency savings and supporting the family’s well-being. However, besides financial rewards, other job characteristics and personal occupational preferences come into play: namely, the extent of social protection, the work–life balance, job flexibility, an aspired to technical skill level and learning opportunities, the presence of labour union representation, income stability and, last but not least, outspoken preferences for work in certain sectors (public or private; wage or self-employment; agriculture, manufacturing or services). What it is exactly that young people worldwide aspire to and find important in a job is an empirical question and varies according to individual preferences and the socio-economic and institutional environments in which they live.

4.1.2 Labour markets and realistic aspirations

The framework conceives three levels of aspiration – low, realistic and high – for a given set of skills. As previously discussed, aspirations and action can be seen to follow an inverted U shape, where realistic levels of aspiration are at the top of the arms of the U and most conducive to successfully aspired to outcomes.

Figure 4.1 Aspirations and labour markets

In figure 4.1, the diverse set of aspirational dimensions for a given set of skills is represented by the arrows. Each arrow represents a particular dimension (income), and aspirations can range from low to realistic to high. Individuals may develop strong aspirations in one particular dimension and weaker ones in another. To demonstrate the links between the different dimensions, take for instance, a person who is hoping to have an enjoyable work–life balance: their aspired to salary may be a little lower than for career-driven young people, for whom salary and career development goals will be strong but with less of a work–life balance. How people prioritize different aspirational dimensions is partly determined by preferences and socioeconomic environment and, again, the labour market.

Local labour market conditions influence the range of realistic aspirations and successful labour market outcomes, as represented by the darker colour (see figure 4.1). Yet, labour market conditions alter in response to the technological, social and economic forces that shape supply and demand, thereby shifting and potentially increasing or decreasing the range of realistic aspirations available. Technological change influences how production factors, such as capital and labour, relate to each other and determines the skills required from workers. Automation and robotization may replace workers with machines and drive low-skilled workers and increasingly medium-skilled ones out of the market, thereby decreasing the likelihood that low- and medium-skilled people will find another job, earn a decent income and work at the technical level to which they aspire. Hence, labour markets that are more challenging affect how large is the range of aspirations that individuals are likely to achieve.

Along with technological change, social forces may shape labour market conditions. A minimum wage structure, social protection and employer–employee relationships are largely the result of labour market policy interventions targeting the challenging evolutions in the labour market. Labour markets that are more flexible can fuel the aspirations of people who want to combine jobs with study, family or life quality, but they can depress aspirations in, say, the dimension of social protection or career development.

Hence labour market forces and labour market policies jointly determine how narrow or wide is the range of realistic aspirations for any given skills set. A limited range can motivate people to engage in education and skills development in order to open more perspectives, feeding into new future aspirations.

4.2 Labour market trends and their implications for aspirations

There are currently various labour market trends with the potential to affect aspirations. In particular, technological change, instigating robotization, automation and an increasing use of information and communication technology (ICT) in the workplace, is leading to non-standard forms of employment and new employer–employee relations. This may have many implications for what can realistically be aspired to in the various aspirational dimensions, including social protection and job flexibility. These evolutions in the labour market and their implications for aspirations are discussed in brief below.

4.2.1 Non-standard forms of employment

Over the past decades, one of the most prominent features of global labour markets has been the growth in non-standard forms of employment (NSE) (ILO, 2016). In contrast to nine-to-five wage work, NSE incorporates (1) temporary employment, (2) part-time and on-call work, (3) multi-party employment relationships and (4) disguised employment and dependent self-employment (ILO, 2016).

This evolution clearly broadens possibilities in terms of job flexibility or work-life balance, but narrows expectations for young people who aspire to a full-time wage job providing a decent and stable income. For most workers, employment in NSE is accompanied by job insecurity and even working poverty. In many low-income countries, NSE has come to dominate the labour market in the form of informal employment or employment in informal sectors.

Own-account workers (self-employed without employees) made up over a third of all global employment in 2018 (ILO, 2019). Surveys show that in Europe individuals who are self-employed are often motivated to be so for positive reasons, such as autonomy and a better work–life balance, and that they are generally well remunerated. However, there are also negative motivations driving people into self-employment; increasingly, employers like to work on an ad-hoc basis with professionals who are self-employed in order to flexibly match the size of their workforce to the business cycle in anticipation of fluctuations in demand (Eurofound, 2018).

Hence, non-standard jobs are also associated with increased fragility and precariousness. They are hit hard by negative demand shocks and may not benefit equally from the social security system, including pension and unemployment benefits, and they tend to be found amoung youth in particular (O’Higgins, 2017; Chandy, 2017; Bruno et al., 2014; Gontkovičová et al., 2015). Being in NSE reduces the possibility of receiving on-the-job training and gaining from professional guidance, which can have a negative effect on career development (ILO, 2016). In addition, young workers who are informally employed have a higher risk of being in and out of employment, which could discourage them aspiring to a higher employment achievement (Beyer, 2018). In some cases, hardship for youth in entering job markets and securing stable employment may lead to frustration and drive them into being inactive (Arpaia & Curci, 2010).

4.2.2 Technological change and demand for work

The influence of technological change on the demand for labour and its impact on the aspirations of youth is another cause for concern. Technological change may entail automation, replacing people by machines. Concern about robotization and automation was at the centre of academic and policy debates following the publication of Frey and Osborne’s (2013) influential paper revealing that around 47 per cent of 702 occupations examined in the United States are at risk of replacement by computerization. Subsequent research, mainly in OECD countries, has confirmed what Frey and Osborne found, but gone on to demonstrate that technological advance may also create a considerable proportion of new occupations for the young. “

Irrespective of its potential magnitude or speed of impact, “skill-based technological change” is certain to alter the set of

Additionally, the impact of technology on jobs and workers will be clearly uneven across countries. It will depend on a country’s level of development, its adaptation to new technologies and how well the labour force is prepared for the changes technology brings (Acemoglu & Autor, 2011; ILO, 2017a). Through foreign direct investment, technology diffuses rapidly. For a limited time, young labour market entrants in less developed countries might remain exempted from the influence of frontier technology, but they will need to adapt to the technology-driven world eventually (ILO, 2017a). In South Africa, for example, the IT-enabled services sector is growing fast, providing jobs for an increasingly large pool of medium-skilled workers conducting business processing services, such as administrative, legal and after sales services for large foreign customers’ firms (Keijser, 2019). In Ethiopia, evidence shows that foreign firms have increasingly sought skilled workers, but where export activity is involved there was a higher demand for unskilled workers, due to the country’s comparative advantage still being its low-cost labour (Haile et al., 2017). More jobs is desirable for a country with a youth bulge ready to enter the labour market, but the effect of technology on occupations’ skills and wages may differ between countries and may serve to either reduce or reinforce social exclusion for disadvantaged youth. These evolutions will ultimately be reflected in the beliefs, experiences and social networks of the young people developing aspirations, and hence influence what can realistically be achieved by young people equipped with a particular skills set.

4.2.3 IT-enabled opportunities and social protection

Technological change has also spurred the expansion of a range of more flexible working arrangements. Especially digital innovation decentralizes the unit of economic activity from corporations to individuals, affording workers more chances to participate in labour markets as entrepreneurs (Chandy, 2017).

The growing gig (platform) economy is fuelling the growth of various types of flexible employment and self-employment (De Stefano, 2016; Katz & Krueger, 2019). This may take the form of crowd work, whereby work is posted on Internet platforms to the “crowd” and customers and contractors can then manage it through either a digital platform (ILO, 2019) or “work-on-demand via apps”, with examples such as Uber, Airbnb, TaskRabbit. This may serve to free people from geographical restrictions and create more flexible job opportunities for all.

Nevertheless, this all comes at the risk of weak social protection related to NSE, as described above (Smith & Leberstein, 2015). The growing group of “platform workers” is not contractually employed by customers, so their status is one of legal uncertainty in the labour market. The flexibility of employment can be a sword that cuts both ways; it grants working autonomy but can also isolate workers and weaken their bargaining power (Codagnone, Abadie, & Biagi, 2016). In the long run, the platform employment may endanger income stability, increase unemployment and exclude workers from social security coverage.

The heterogeneous effects of technological change on global labour markets creates uncertainty for the future of work, which brings more challenges to the youth of today than previously experienced by their parents’ generation. As indicated in the preceding section, young people are starting careers in diverse forms of unstable and insecure employment (ILO, 2017a). Meanwhile, while young people still associate the ideal job with aspects of more traditional forms of employment, such as a good salary, career development opportunities and social protection, they are also increasingly open to greater flexibility in their job and a good work–life balance. In many parts of the world, the gap between career aspirations and labour market reality is widening, to a point that it may hurt young people’s chances of employment. A recurrent issue is youth in developing countries aspiring to a decent formal job in the public sector where job offers are in decline, often leading to unemployment, as seen in a study on Ethiopia (Mains, 2012). Therefore, in order to help youth mobilize their aspirational strength, we need to better understand their aspirations in life and at work. This includes what they value most in their work, what they aspire to for the future and how these aspirations can be aligned with future job or career development perspectives through policy interventions that help them develop the right skills set for the aspired to positions and which cushion labour market shocks. This calls, in the first place, for a survey of the existing empirical evidence of (drivers of) aspirations of youth around the world to help identify evidence gaps and contribute to the development of better evidence-based labour market policies.

Measuring youth aspirations in the world of work: an overview of existing surveys and indicators

Recent surveys focusing on youth (or sub-populations of youth) have included questions about aspirations or goals for the future, about what they value in a job or career, and about their beliefs and worldviews. While these surveys did not have as a primary objective collecting evidence of youth aspirations in the labour market, many touch on particular aspects or dimensions of youth (career) aspirations. They are therefore a good starting point when considering the methodologies applied so far and for bringing together for a first time in a systematic overview the evidence on youth aspirations.

Subsection 5.1 provides a brief overview of the surveys selected, drawing on the information presented in Appendix A. Subsection 5.2 describes how the surveys have been operationalized according to aspirations, expectations, or beliefs or values that contribute to shaping or driving aspirations. Detailed examples of questions taken from different surveys are presented in Appendix B as illustrative of the similarities and differences between the survey instruments reviewed for this study. The next section (section 6) presents the evidence.

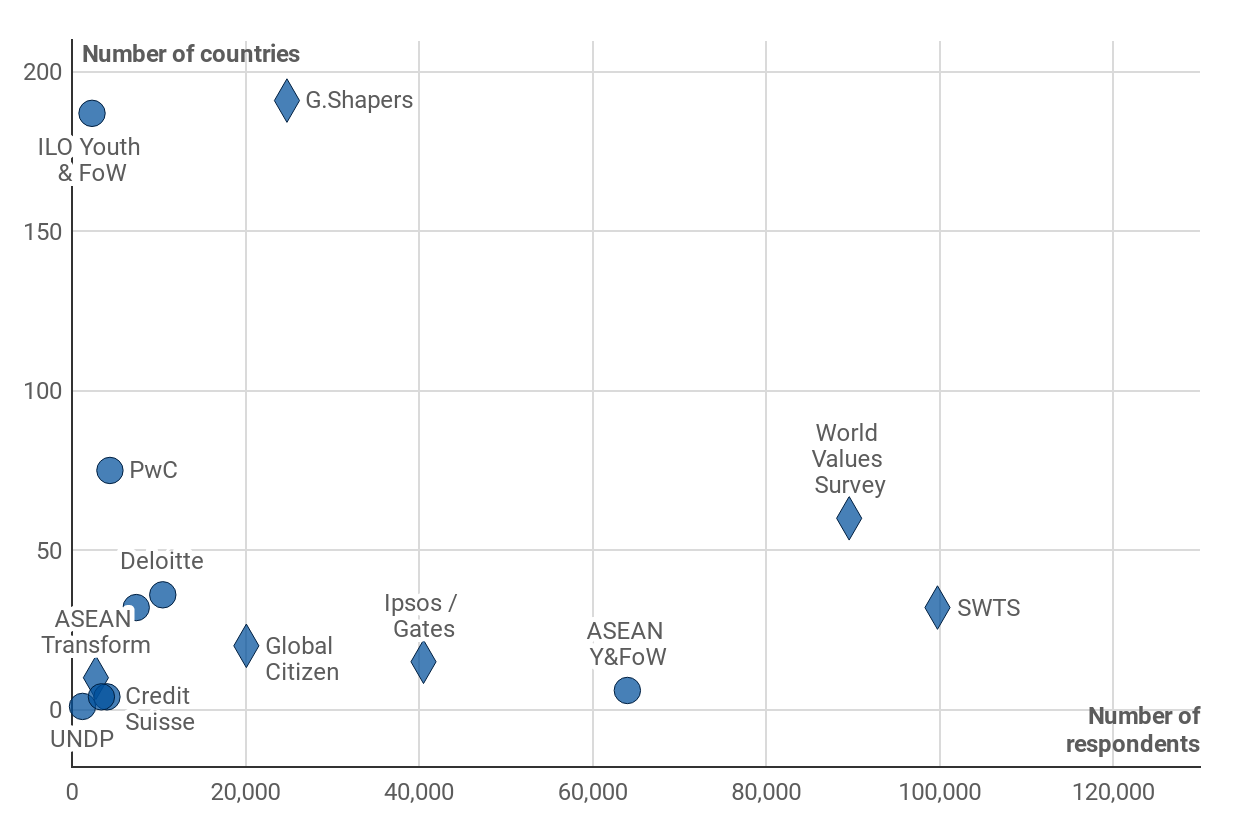

5.1 Data sources: discussion of data sources, coverage, target groups

Eighteen surveys were identified with relevant indicators for various dimensions of youth (labour market) aspirations. The surveys selected have all been conducted within the last ten years and many within the last three. They do, however, differ widely from one another and this makes comparisons sometimes difficult. For instance, the number of countries covered, the number of respondents and the mode of delivery varies considerably between surveys. Modes of delivery include online, SMS messaging, face-to-face surveys and Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI). Surveys that use the Internet to collect responses are able to reach respondents in more countries than otherwise.

To give a brief overview,

Figure

Note: ASEAN Transform: ASEAN in Transformation; PwC: PricewaterhouseCoopers; SWTS: School-to-Work Transition Survey. This figure does not include all the surveys; for example, the preliminary report for the Youth Speak Survey conducted by AIESEC reports neither the number of countries nor the mode of survey delivery.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, based on information provided in the reviewed reports on the number of countries and respondents.

The most important difference between the surveys selected is the target population. A majority targets youth populations, but the exact age range varies; indeed, some even target entire populations, including adults. The population surveyed is often further restricted beyond just the target age range. Restrictions may occur by default; for instance, due to the channels or modes of delivery by which a survey reaches potential respondents. For example, the ASEAN Youth and Future of Work survey (see more details in Appendix A, table 2) collected responses via online e-commerce or gaming platforms. Restrictions are explicit when the survey’s declared aim is to solicit responses from youth with specific characteristics (i.e. students); for example, Deloitte (see more details in Appendix A, table 5) surveyed millennials with a university degree who were employed full-time (mostly in large, private sector companies).

Both these types of restriction are potential sources of bias,

A study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (see more details in Appendix A, table 15) set up 64 polling sites to interview youth in Armenia, aiming to yield a nationally

In Appendix A, table 1 through table 18 summarize information about the year the survey was conducted, the number of countries, the target age group, number of respondents and restrictions (by default or explicit) on the sample population. Each table includes a statement describing the objective of the survey; a statement describing the mode of survey delivery; and a short discussion about the survey’s respondents. The sources of information used to describe each survey come from either the survey itself, the documentation supporting the survey or reports written about the results of the survey.

5.2 Indicators of work-related aspirations

This subsection discusses the operationalization of indicators with reference to the specific questions put to respondents by the different surveys (presented in Appendix B.). Questions are classified into question groups, depending on the dimension measured (ability, beliefs/perceptions, desire/values, drivers and perceptions thereof, e.g., labour market perceptions), as discussed in the literature.

The state-of-the-art in terms of the current theoretical and empirical literature on aspirations has been covered earlier by section 3. Naturally, concepts must be operationalized in order to be measured in social science research.5 Therefore, in the review of survey questions that measure aspirations, the distinction between different dimensions of aspirations has been isolated and amplified. In theoretical section 3 above, aspirations are characterised as “the personal desires of individuals (preferences and goals), their beliefs about the opportunities available to them in society (opportunities and pathways) and their expectations about what can be achieved through their own effort in an uncertain future (self-efficacy and agency)”.

We identify survey questions that tackle the first dimension, which we call the “goal dimension of aspirations”, including career goals and the related “desired values and characteristics of jobs (or careers)”. “Expectations” are defined as a concept related to aspirations, in that it combines goals and preferences, on the one hand, with pathways and agency on the other. We identify questions that fit this description. We further identify questions assessing pathways and opportunities, or a lack thereof, by selecting those questions that ask for “perceived obstacles to achieving aspirations”. We distinguish between these perceived obstacles from perceptions and beliefs about technology, and from general perceptions about the world.

We were unable, however, to identify in the above mentioned surveys any questions that could be used as a measure of “self-efficacy and agency”.

5.2.1 The goal dimension of aspirations

In accord with the notions set forth in section 3 based on the theory of hope, we have classified the questions in Appendix B, table 1 as ones that operationalize the aspired to goals. Many of the questions are phrased in a way that asks individuals about their preferences or

Response choice varies between surveys. While many ask young people similar questions about their preferred sector of work or job, the response choices yield different kinds of information. For example, some surveys offer relatively broad responses categories for preferred sector of work, while others classify sectors in a more detailed way. To illustrate this variation, Appendix B presents the response choices in table 2 that correspond to the questions presented in table 1.

The desired/preferred job characteristics dimension is closely linked to the aspirations literature stating that aspirations capture the personal preferences of individuals (along with beliefs about the opportunities available to them in society, and expectations as to what can be achieved through their own effort in an uncertain future). In the context of work, this translates into survey questions which ask youth about what characteristics their ideal jobs would have (or similar phrasing). We assume this to be an underlying driver leading young people to form aspirations of working for a particular type of organization, or in a particular sector, hence preferred job characteristics and aspired to goals are interlinked. See Appendix B, table 3 for examples of survey questions related to a respondent’s desired or preferred job characteristics.

5.2.2 Expectations

As explained earlier in section 3, when what we aspire to for our future (aspirational goals) is aligned with what we believe can be achieved given the right circumstances (opportunities), and through your own effort, aspirations become analogous to expectations. Most of the questions in Appendix B, table 4 actually contain the word ‘expectations’ in relation to career goals, or ask respondents what they think will take place.

By asking youth about perceived obstacles to getting a job, answers reveal perceived limitations or constraints to achieving the goal of getting a job, reflecting a perceived lack of opportunity. In the context of youth and the future of work, this question may serve to highlight an important gap between aspirational goals and successful outcomes.

Youths’ assessment of the value of education, apprenticeships and particular labour market opportunities might also have an affect on aspirations achievement. Examples of survey questions that operationalize this notion are presented in Appendix B, table 5.

5.2.3 Perceptions/beliefs about technology

There is a fierce debate and a wide range of opinions regarding how new technologies are likely to affect employment opportunities. These range from a deep fear that jobs (or tasks within jobs) will be destroyed to a more general technological optimism that, ultimately, new technologies will create new jobs. Digitalization, automation and robotization are predicted to change the very nature of how we work. This is an important issue for all groups of people, but perhaps of most concern for today’s youth, who are either new to or entering the labour market. That said, young people have been exposed to some of today’s technologies from a younger age than older generations and may be more comfortable and competent with technology and therefore not feel as threatened by these new technologies as perhaps are older generations (see the earlier discussion in subsection 4.3). Examples of survey questions asking youth about their perceptions regarding technology and its implications are presented in Appendix B, table 6.

5.2.4 General perceptions/beliefs about the world

Appendix B, table 7 highlights examples of survey questions capturing general perceptions about the world and future possibilities that might help shape aspirations. The framework developed earlier in subsection 3.3 describes how aspirations are developed and achieved and how lived experiences and social messages and beliefs feed into aspiration formulation.

Youth aspirations and the world of work: Global evidence

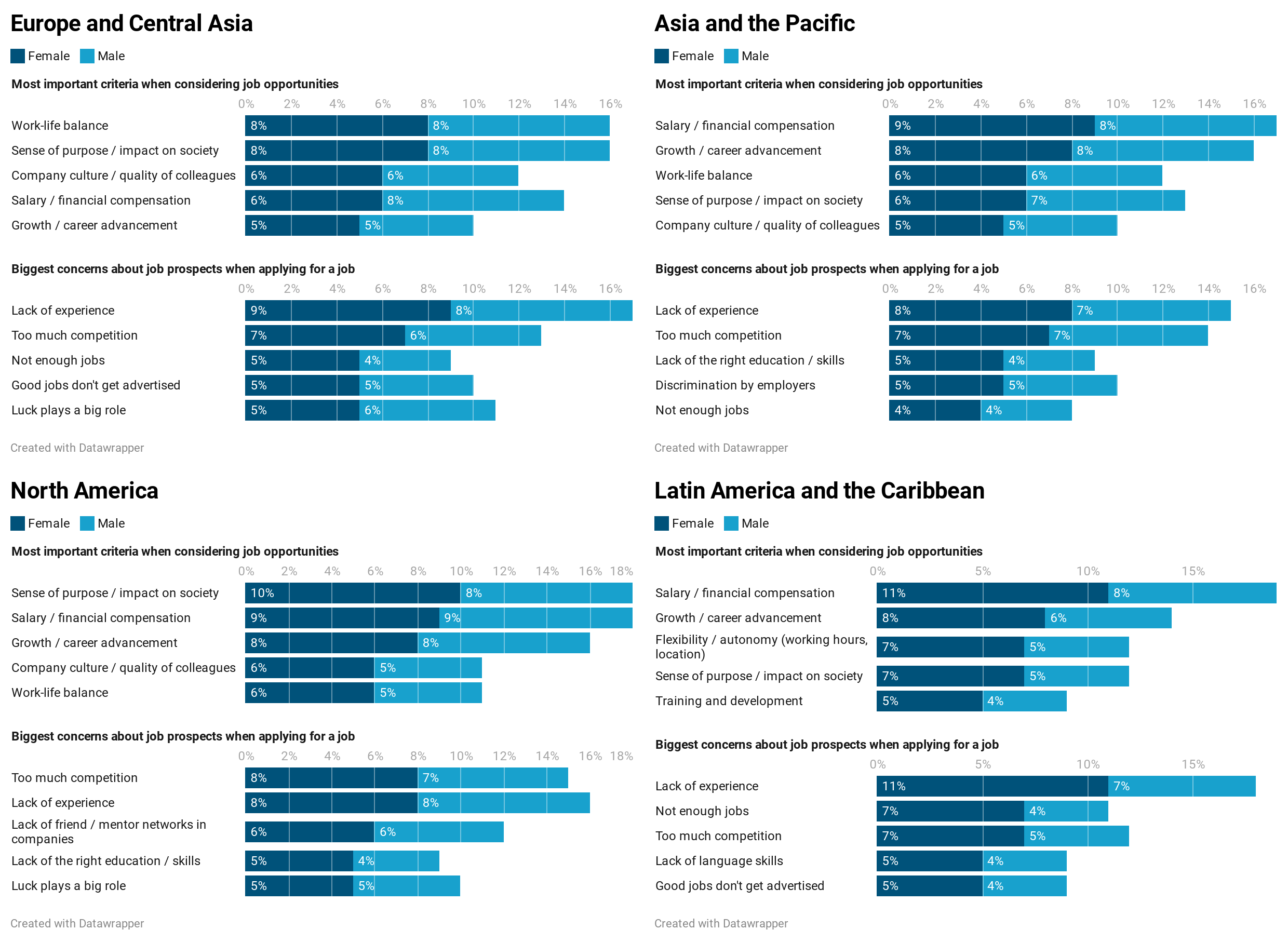

The global trends in young people’s career aspirations as revealed in the data are discussed in this section. Indicators of aspirations or sub-dimensions thereof (specifically, perceptions of labour market challenges, most valued characteristics of a job) are presented and then data is compared by region and by gender.

Data from the Global Shapers Survey is used as a basis for the analysis. The Global Shapers Survey targets young people (aged 18–35) and has one of the most extensive country coverages (191 countries) from among the surveys reviewed for this report. In total, there were 24,766 respondents. Responses were collected via online and offline channels, together with some workshops designed for a wider range of respondents. However, despite attempts to increase its reach, the Survey makes no claim to representativeness. The Survey collected background information (including on gender) and grouped questions into themes such as “values, outlook, and workplace”. The data also contain information about a respondent’s region. For these reasons, the data from this survey was used to explore the sub-dimensions of aspirations, together with expectations and the perceptions of youth regarding whether technology is likely to create or destroy jobs in the various regions around the world.

6.1 Regional trends

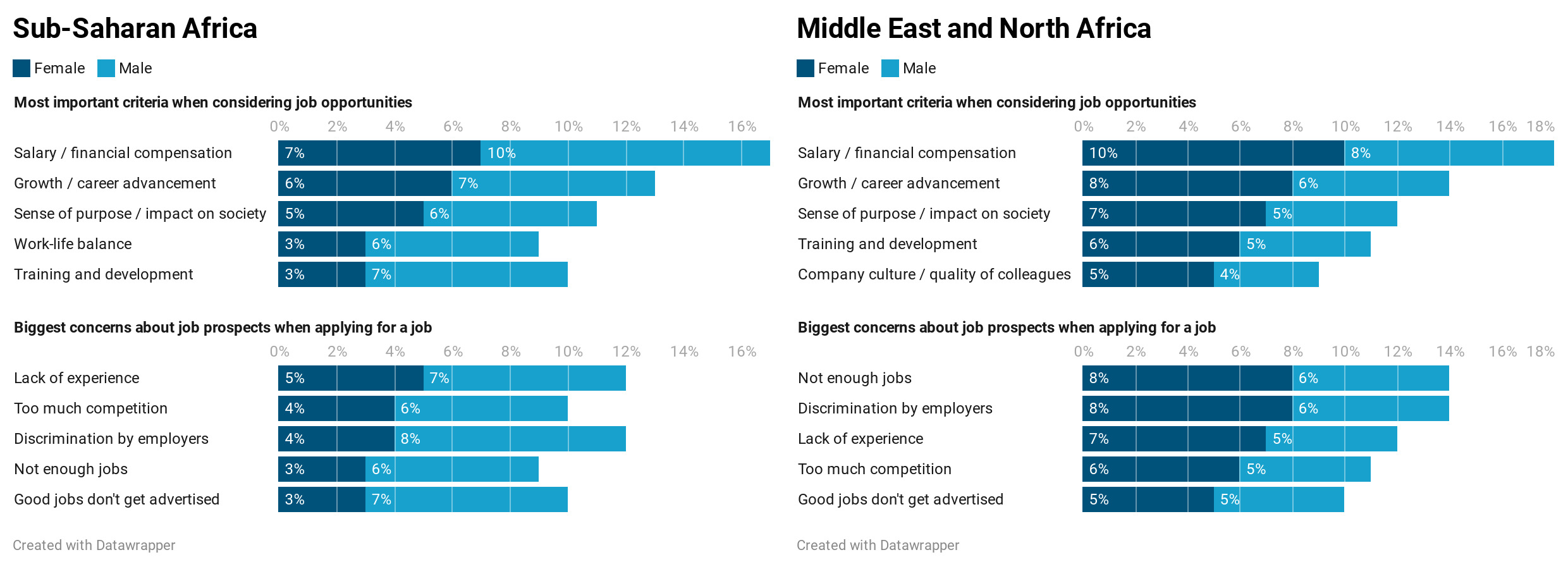

In Asia, salary and financial compensation is ranked first by young women in this region, whereas growth and career advancement ranked top for young men. Women value the opportunity to travel internationally more than do men and young women and men both have lack of experience and too much competition as their two biggest concerns when applying for a job. But, a greater percentage of young women indicate discrimination by employers as being a concern than do young men.

The most striking finding for Europe and Central Asia is that, in contrast to every other region in the world, youth did not rank salary and financial compensation as the most important criterion for a job. More young women identified sense of purpose and impact on society together with work–life balance as being more important than salary and financial compensation when considering a job. More young men chose salary and compensation, but sense of purpose and impact on society ranked second. Like their counterparts in Asia, young men and women in Europe worry about lack of experience and too much competition. In Europe, more women than men cite discrimination by employers and not enough jobs as concerns.

In North America, similarly to Europe, more young women than young men nominated sense of purpose and impact on society as important to them, but in North America a greater proportion of young women cited flexibility and autonomy as important. Consistent with other regions, young men and women both worry about lack of experience and competition, but more also identify lack of social networks and luck as factors when applying for jobs.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, salary and financial compensation and growth and career advancement topped the chart for young women and young men alike, but greater proportions of women chose sense of purpose and impact on society and flexibility as of importance. While lack of experience and competition are again the biggest concerns, many more youth nominated there being not enough jobs as a major concern than in other regions.

In Middle East and North Africa, while salary and financial compensation and growth and career advancement ranked top for both young women and young men, a larger proportion of women valued a work–life balance, which is not surprising considering household duties tend to be assigned to women in this region. Both young women and young men cited discrimination by employers as the biggest concern when applying for jobs. This may be gender discrimination or segregation, following the observation that particular jobs are reserved for particular sexes. Furthermore, both young women and men indicated that there are not enough jobs available.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, a large proportion of young men cited training and development as the most crucial criteria when considering job opportunities and discrimination by employers as a major concern, while women cited “sense of purpose” as the third most desired job characteristic. All youth in every region were most worried about lack of experience when applying for jobs, and in sub-Saharan Africa it is no different.

Figure

Sources: Own elaborations based on Global Shapers Survey (2017).

Notes: Respondents could select up to 3 out of 10 responses, hence totals do not add up to 100 per cent. The 11 responses for “Most important criteria when considering job opportunities” were (i) company culture/quality of colleagues (ii) dynamic and growing enterprise, (iii) product/service quality, (iv) opportunity to travel internationally, (v) reputation of company/social status, (vi) flexibility/autonomy (working hours, location), (vii) work-life balance, (viii) training and development, (ix) sense of purpose/impact on society, (x) growth / career advancement, (xi) salary/financial compensation. The 11 responses for “Biggest concerns about job prospects when applying for a job” were (i) lack of language skills, (ii) lack of presentation/soft skills, (iii) luck plays a big role, (iv) geographical constraints, (v) good jobs don’t get advertised, (vi) lack of friend/mentor network, (vii) not enough jobs, (viii) lack of right education/skills, (ix) discrimination by employers, (x) too much competition, (xi) lack of experience. Respondents from East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia have been combined in panels showing Global Shapers Data

To summarize the findings from this analysis: if we plot the percentage of youth who selected salary and financial compensation as one of the three most important criteria when choosing a job by the level of human development in their country, an inverse relationship can be seen. That is, the lower the human development index, the greater the proportion of youth who nominate salary as one of the three most important criteria when considering a job opportunity.

We can contrast this relationship with the inverted U-shaped relationship found when opportunity to travel internationally is plotted by human development category. In the lowest and highest human development categories, international travel is cited less often than it is in countries in the mid-to-high range of human development. This finding accords intuitively with a hierarchy of needs perspective: once financial needs are met, other interests and needs can begin to emerge. In countries with the highest level of human development, there may simply be less incentive to travel abroad to seek opportunity.

Figure 6.2. Different important job criteria, by human development category

Source: Own elaborations based on Global Shapers Survey (2017)

Notes: The y-axis is different in each panel, although both span 5 percentage points, there is a far greater proportion of respondents (in all human development categories) who selected ‘Salary / financial compensation’ as one of the three most important job criteria. This would be evident from studying figure 6.1 above.

6.2 Technological change and jobs

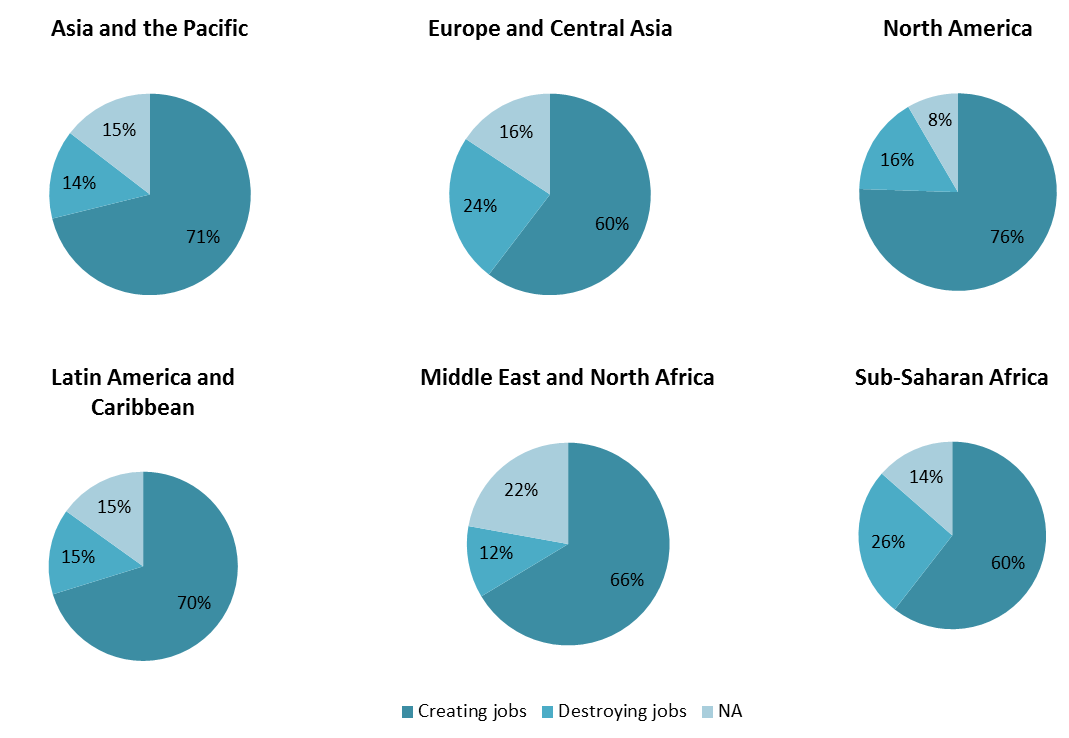

The Global Shapers Survey, like many other surveys reviewed in this report, asks young people about their perceptions regarding whether technology is creating or destroying jobs. Figure 6.3 gives a regional overview of responses to the question: “In your opinion, technology is…”. Possible answers were: creating jobs, or destroying jobs, or NA.

Figure

In Asia, youth were overwhelmingly positive about technology creating jobs, which supports evidence found in other surveys conducted in countries in the ASEAN region. In Europe, youth are much less optimistic about technology creating jobs than their counterparts in Asia and North America. The only other region where only 60 per cent of youth believed that technology is creating jobs is sub-Saharan Africa. The youth most optimistic about technology creating jobs are in North America. In Latin America and the Caribbean, a relatively high percentage (70 per cent) of youth in the region believed the same. In the Middle East and North Africa region, 66 per cent of the youth were optimistic that technology is creating jobs.

It is possible that differences might arise, because of the different age groups surveyed; considering the rapid rate of change of today’s technology, the age range across the surveys selected (18–35 years of age) spans a long time-horizon. Nevertheless, generally speaking, there was not too much difference between 5 sub-age groups with regards to the opinions they held about whether technology is likely to create or destroy jobs. Interestingly, the youngest sub-age group (18–21 years of age) had the smallest fraction of respondents (64 per cent) that thought technology creates jobs. In fact, the results for ages 27–30 were exactly the same as for ages 31–35 (68 per cent thought that technology creates jobs). Ages 22–26 were almost as optimistic (67 per cent).

Making use of the background information collected by the Survey, we explored further how the answers about technology changed depending on employer or sector of employment in figure 6.4. Only 60 per cent of young people who were unemployed believed that technology is creating jobs, whereas 71 per cent of people working for either non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or international organizations believed this to be true. There is no marked difference apparent between unemployed youth and other youth who are employed in different sectors as regards the opinion they hold about this question. It is important to note that there are fewer respondents who are unemployed vis-à-vis the number of respondents who are students or working in the private sector, so we ought to be cautious and not draw too strong conclusions about unemployed youth.

Figure

.png)

Source: Own elabouration based on Global Shapers Survey (2017)

Using the World Values Survey, in figure 6.5 we juxtapose the viewpoints of people regarding whether the world is either better or worse off because of technology with the percentage of respondents who had never used a personal computer. The map in the left-hand panel illustrates survey respondents’ sentiments as to whether the world is better off because of science and technology. The response scale was from 1 (a lot worse off) to 10 (a lot better off). The lowest mean for any given country is a 5.87 and the highest 8.87. Most countries are in some shade of yellow to green, indicating a country mean of 8 or above. So, generally speaking, people are quite positive about the world being better off because of science and technology. The map in the centre panel is about how frequently respondents used a personal computer. Countries in green had among the highest proportion of people who had never used a personal computer; the maximum was in Zimbabwe, where this was true of 72.4 per cent of respondents. Countries in red had a very small proportion of people who had never used a personal computer; the smallest was in the Netherlands, where it was true of only 1.7 per cent of respondents. The right-hand panel shows a scatter plot for these two indicators. Clearly the range of responses for perceptions regarding science and technology is far smaller than the one for the percentage of respondents who have never used a personal computer. The correlation between the two indicators is very low, almost zero (0.04).

We ran a similar exercise for the percentage of respondents who said that their job was mostly manual and found that for those countries where respondents’ job tasks are mostly manual there is a 0.3 correlation with the perception that the world is better off because of science and technology. This is still a relatively low correlation coefficient, but not as negligible as the correlation between use of a personal computer.

As an illustrative example, let us consider India. Despite the fact that the vast majority of respondents in India considered the world to be better off because of science and technology, 59.3 per cent reported that they have never used a personal computer, and almost 18 per cent indicated that the nature of their tasks at work was mostly manual. This does not mean that people in India should not be optimistic about science and technology. The ICT industry in India has afforded many opportunities in the country and cell phone technology has increased access to finance. But, if almost 60 per cent have never used a personal computer and 18 per cent have manual jobs, it does call into question whether people in India are equipped with the basic computer skills necessitated by technological change and future labour market trajectories.

Figure 6.5. Perceptions of technology, juxtaposed with actual personal computer use

Source: World Values Survey, 2010–14 (6th Wave). Online analytics for the maps and own elaboration using World Values Survey data for the scatter plot.

6.3 Aspiration gaps and aspiration failures

The 2017 report

The OECD’s findings are summarized in

What the OECD found from the School-to-Work Transition Survey (SWTS) data is that students in the countries surveyed overwhelmingly aspired to work in the public sector. Across countries, this was the case for an average of 57 per cent of those surveyed. This is at odds with the fact that only 17 per cent of young workers were employed in the public sector at the time of the survey (which includes state-owned enterprises, international organizations, NGOs and public companies). Similarly, in most countries, more youth expressed a desire to work in the private sector or self-employment or for a family business than actually do. Another risky mismatch is that the high percentages of students who desired high-skilled work will most likely be unable to fulfil those aspirations (even tertiary students), given the current labour market trajectories (ibid., p. 13).

Figure

Source: OECD (2017). OECD’s calculations based on SWTS 2012–15 data.

Notes: The figure shows the difference in the share of young students in the country who say they want to work in that sector and the actual employment of young people in that sector. Within each region, countries are sorted by the difference between reality and desire (aspirational gaps). 1Data for El Salvador are urban only and 2data for Montenegro, Togo and Viet Nam are missing sample weights.

The OECD offers several policy recommendations to curb the mismatch between young people’s labour market aspirations and reality. The first is to provide youth with information about labour market prospects to help guide their career choices. Indeed, around 33 per cent of respondents to the Citi and Ipsos survey said that if they “knew where to find information about job opportunities”, it would make it easier to find a job. Yet, the most cited need of around 48 per cent of respondents was “more on-the-job-experience” (Citi and Ipsos, 2017).

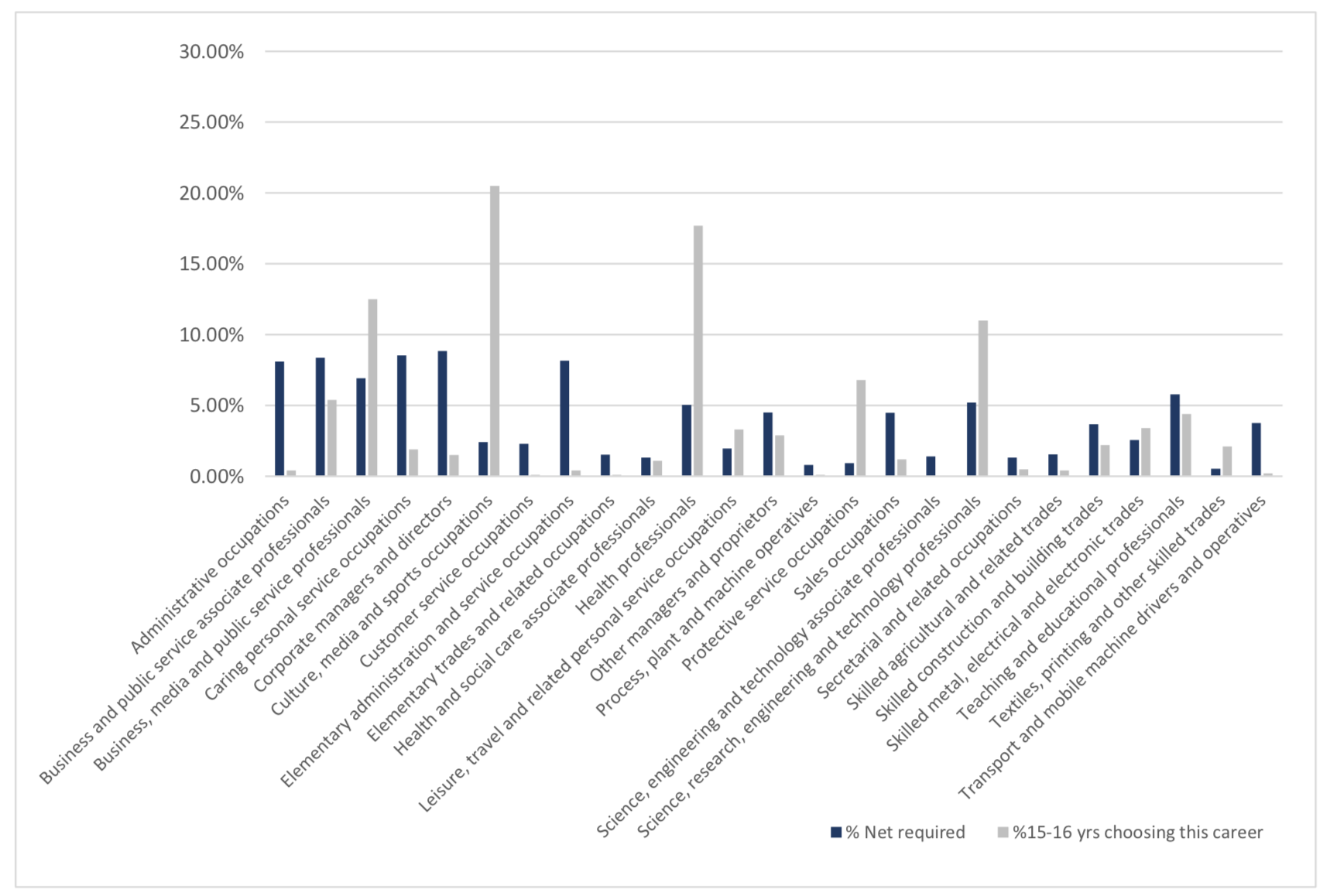

While the OECD analysis gives some information about aspirational gaps, we only see the mismatch for a broad classification of sectors (public and private) and it would be instructive to have an analysis based on economic sector of employment or actual occupations. For example, an analysis conducted by Education and Employers together with the United Kingdom’s Commission for Employment and Skills and B-live found the aspirations of people aged 15–16 to have “nothing in common” with actual and projected demand in the workforce (as cited by Chambers et al., 2018).

Figure 6.7 is excerpted from the

Figure

Source: Excerpted from Chambers et al., 2018

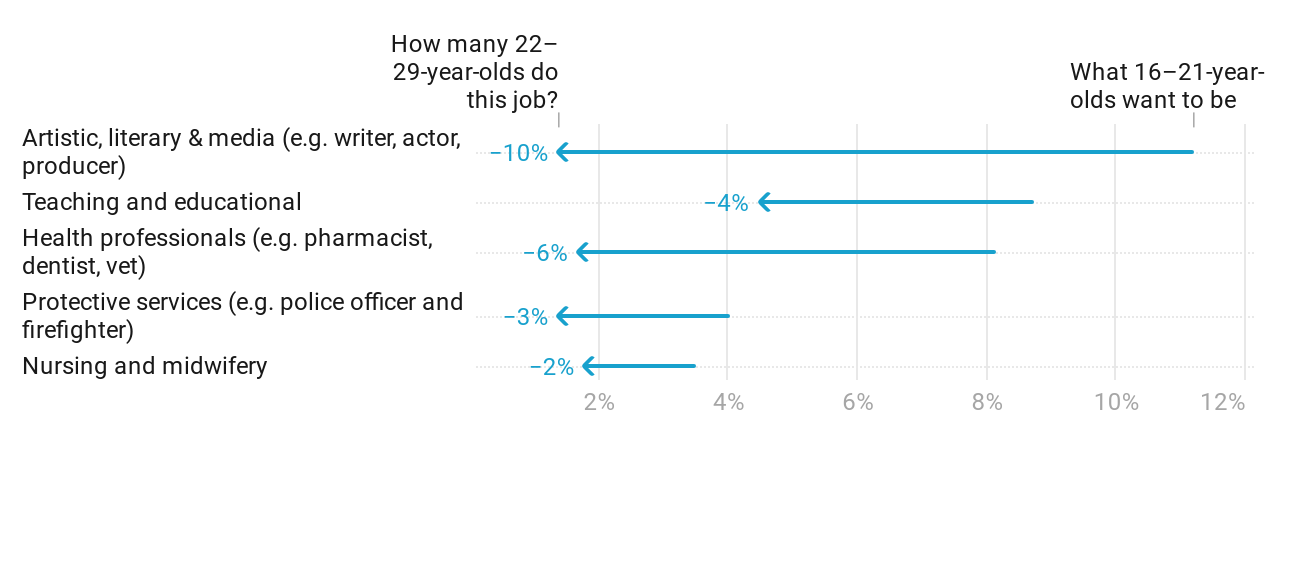

Chambers et al. noted that these findings raise a major concern about the extent of the gap between jobs that actually existed (or were projected to exist) and what young people aspired to do and related this to a lack of information. The Office of National Statistics in the United Kingdom published a blog in September 2018 expressing a similar concern. They found that the top five dream jobs for young people aged 16–21 in 2011–12 did not align with the proportion of persons aged 22–29 in those occupations in 2017.

Figure

Source: United Kingdom Office for National Statistics blog, available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/youngpeoplescareeraspirationsversusreality/2018-09-27

A study conducted in Switzerland in 2010 found that around 80 per cent of young people in grade seven (aged 13–15) who were predominantly non-college bound had at least one realistic career aspiration (Hirschi, 2010). The Swiss education system is a dual system whereby around two-thirds of students go into vocational education and training in grade nine. The study asked 252 students to name the vocational education or training or the school they were considering after grade nine. Students could list as many options as they wanted (Hirschi, 2010). Due to the particular structure of the Swiss education system, it was possible for the author to build a measure of how realistic was this aspiration. This analysis is quite distinct from the studies conducted in the United Kingdom, but one interesting difference stems from students being allowed to mention as many aspirations as they wanted. For all but 20 per cent of respondents, at least one of those mentioned was realistic. This suggests that the way in which responses are solicited can yield different “matches” with reality; if a young person can list multiple career aspirations, what are the chances that at least one is consistent with labour market demand? This is a different question from the one analysed by the Office of National Statistics and Education and Employers in the United Kingdom.

The OECD’s second recommendation for reducing aspirational gaps is the promotion of entrepreneurship for young people who possess a high degree of entrepreneurial potential. According to the OECD’s report, youth identified self-employment and working for a family business as desirable, when through choice or because their family needed help (OECD, 2017). However, it is known that entrepreneurship in many developing countries is typically undertaken through necessity rather than choice therefore promoting more innovative types of entrepreneurship is crucial. Acs et al. (2008) have argued that positive perceptions of the opportunities available in the environment where one lives and about one’s own entrepreneurial capabilities drives people into opportunity entrepreneurship, a mechanism that clearly corresponds to the drivers of aspiration formation as described earlier in section 3. Box 6.1 presents the results of a recent study on differences between entrepreneurial attitudes and a country’s level of early-stage entrepreneurial activity.

Box 6.1 Entrepreneurial attitudes and entrepreneurship

|

Beynon et al. (2016) took a sample of 54 countries from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2011 survey to analyze four country-level entrepreneurial attitudes and assess their role in driving Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), which has been related to a strong business culture and growth. Entrepreneurial attitudes are defined in the table below.

Source: Excerpted from Beynon et al., 2016. The authors found that for a majority of countries high TEA levels of entrepreneurship related most to entrepreneurial intention, perceived capabilities and lack of fear of failure, rather than perceived entrepreneurial opportunity (with intention). The results from this study, coupled with findings from Acs et al. (2008), suggest that stimulating entrepreneurship requires helping young people build skills, beliefs in capabilities and self-efficacy, and the desire to engage in entrepreneurial activity. In this sense, the OECD’s proposed recommendation to stimulate entrepreneurship programmes by boosting access to financial services and business development services might be more complete if it also promotes socio-emotional skill building. |

6.4 The broader set of aspirations

Some of the survey literature on the broad life goals of youth indicates that work may not be their top priority. This notion was underscored during an interview held by the authors with representatives of UNI Global Union, who emphasized that youth aspirations of today may be different from those of previous generations. Today’s youth “

Figure 6.9, excerpted from a report of the preliminary results from a YouthSpeak survey by the global student organization AIESEC, seems to corroborate this notion. Globally, youth indicated that family, purpose in life, love and friends, were motivating factors that ranked higher than financial reward or achievement.

Figure

.png)

Source: YouthSpeak survey by AIESEC.

Generally speaking, the analysis presented in this section supports the notion that different groups of youth may respond differently to questions about technology, job preferences and the obstacles to getting a job. It is therefore very important to calibrate results from surveys that have more restrictive samples of generally highly educated employed youth (such as Deloitte Millennials and PricewaterhouseCoopers), since they might not capture the voices of youth who are less educated and not employed. Specifically, in the case of technology, it may be important for surveys to calibrate respondents’ perceptions and aspirations with questions that measure expectations about achieving aspirations and about actual use of and familiarity with new technologies. For example, Orlik (2017) argues that some people working in occupations most likely to be affected by digitalization are not necessarily aware of the acute need to reskill and upskill.

Conclusions and recommendations

7.1 Recommendations for data collection

Recent surveys focussed on youth aspiration tend to ask young people about their goals in terms of (a) ideal sector of work, or (b) ideal occupation. These data collection efforts have been important, because without them, little would be known about what type of work young people aspire to and what matters to them in a job or career (OECD, 2017). Of equal importance, as reported by the OECD, is whether existing labour market conditions live up to youth aspirations. There are risks on either side, as described in section 3 of this report. Aspirations that are either too low or too high risk aspiration failure, leading to frustration. It is crucial to balance within the same survey questions about aspirations with questions that assess reality.

The following recommendations are informed by an in-depth review of the research design of youth-focused surveys and structured as advice for researchers planning projects in this area.

-