Online digital labour platforms in China

Working conditions, policy issues and prospects

Abstract

Digital labour platforms have been proliferating in China since 2005, making China one of the world’s largest platforms economies. This article summarizes the results of an ILO survey, conducted in 2019, of workers’ characteristics and working conditions on three major digital labour platforms. Using the survey data generated, this paper provides first-hand information on worker demographics, motivations, and experiences. This paper also compares the findings between the Chinese platforms and dominant Western platforms, the object of previous ILO studies. The paper concludes with a discussion about the need for institutional reforms and suggests some possible avenues for implementing policies to improve working conditions.

Introduction

This paper discusses the development of digital labour platforms in China and includes the results of a survey of over a thousand workers on three Chinese platforms that offer a wide range on online services. The survey provides information about the demographics of the workers, their work history, their working conditions and their reflections on platform work. The paper sheds light on the institutional, legal, and business environment that has underpinned platform creation in China and provides key insights into the operation of digital labour platforms in China. The survey format follows similar surveys conducted by the ILO (Berg 2016; Berg et al., 2018; Aleksynska et al., 2018) providing information on worker demographics, motivations, and experiences and enabling the opportunity for comparison between the Chinese platforms and dominant Western platforms, the object of previous ILO studies.

The paper is structured in five sections. Following this brief introduction, the first section of the paper offers an overview of the development of e-commerce and platform businesses in China. The second section describes the research methodology and the survey undertaken by the ILO in 2019 of 1,071 workers on three major Chinese platforms. This is followed by the third section of the paper where survey results, covering a range of topics including socio-demographic information, tasks completed on the platform, pre-platform work experience and information about workers’ financial situation, are presented. The fourth section of the paper is dedicated to workers’ perspectives and opinions about platforms and their future employment prospects. The paper concludes with a discussion about the need for institutional reforms and suggests some possible avenues for implementing platform regulation.

The rise of digital labour platforms in China

As of December 2016, China had 830 million internet users, giving the country an internet penetration rate of 68 per cent (Woetzel et al. 2017). Some 610 million people, or nearly 75 per cent of all internet users engage in online shopping (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2019) and by 2016, the country boasted 8.32 million online stores which provided employment to over 20 million people. Given the country’s large population and its investment in e-commerce, even relatively small increases in internet penetration have a direct and enormous impact on the total volume of online sales and digital payments. According to Woetzel et al. (2017), in 2016, China’s mobile payments amounted to $790 billion dollars’ worth of individual consumption, a figure that is 11 times greater than that of the United States. In 2018, China’s e-commerce market was already double the size of the United States, and analysts were predicting that its size would further double by 2020, with growth coming disproportionately from third- and fourth-tier cities and from the country’s vast rural hinterland (Fan, 2018).

E-commerce and retail digitalization has generated tremendous value (reaching nearly 6.6 trillion RMB by September 2017) and created market opportunities for affiliated and supporting services and industries (Woetzel et al., 2017). For example, the growth of e-commerce has triggered demand for design, website programming and website maintenance for online businesses, and has bolstered a need for online marketing services. Of particular interest to this paper, internet penetration and the growth of e-commerce has also facilitated the growth of digital labour platforms in China. As has occurred in other parts of the world, digital labour platforms in China have engendered two distinct types of work: ‘work on-demand via apps’, herein

In China, the development of digital labour platforms has occurred with significant government support, particularly from state-sponsored media, which has positioned labour platforms as both a market innovation and an employment opportunity. This development is viewed as particularly promising for young people who are tech-savvy and in need of paid work.1 Similar to the discourse in many Western countries, platform work is seen as a new avenue to promote freedom and flexibility of work and a better way to match workers talents with market needs.2 The government adopted this stance as early as in 2006, less than a year after China’s first platform, K68.cn, was introduced.3 Since then, over 100 Chinese television programs promoting platform work have aired.

But unlike platforms in the West which received, by comparison, limited government support and intervention, Chinese platform developers saw their platforms as distinct from those created by their Western counterparts. Whereas Western platform models were construed as primarily a business solution, the developer of China’s first platform, K68.cn, viewed platform work in China as a mutually beneficial exchange that came to be known as “Witkey,” a term derived from a combination of the words “wisdom” and “key,”. He envisioned platforms as providing an infrastructure to effectively match those in need of wisdom, ideas, input, or assistance with the sources that could provide the “keys” in the form of solutions. Over the past 15 years, K68.cn and a number of other platforms and academics, have come to commonly refer to the work posted on digital labour platforms as Witkey missions (see for example: Han and Cen, 2014).

Since 2005, the types of work available via digital labour plaforms has grown dramatically. As of 2010, the date of the most recent review of platform work in China, there were over 1000 different Witkey categories for both online and offline jobs; 400 of these categories were commonly used (iResearch inc., 2010).

Online platform work available in China is similar to online platform work in other countries. Tasks are completed remotely and require workers to use a computer and have internet connection. Online jobs range from the “microtask” work, characterized as low-skill, frequently repetitive tasks such as product reviews, online surveys, or tagging images, to “macro-task” jobs that require longer working time and sometimes specialized skills, such as logo design and IT programming (see Aleksynska et al., 2018). Clients in need of services can either contact workers directly via their online profiles or they can post jobs for prospective workers to bid on. Job bidding systems are common and workers’ wages can vary significantly depending on the levels of competition among potential workers and available skill, as will be discussed later in Section 2. Online workers are often remunerated upon completion of the work on a per-task, or piece-rate basis; however, there are platforms where workers may be paid an hourly rate. Platforms process payment transactions between workers and clients but deduct a percentage of the total price of services rendered as a platform user fee.

China has also seen a rapid growth of location-based platform work that is coordinated via apps but completed in person, locally. Common services offered via location-based platforms include on-demand food delivery and transportation services. Like online work, location-based platform workers generally receive piece-rates that are paid per tasks once a job has been completed. Pay for delivery and transportation work can vary according to time and distance

Chinese digital labour platforms also offer a third type of services – craft and assembly work—not found in other studies of Western platforms. Common types of craft and assembly work include beading, cross-stitching, fabricating hand-made dolls, printmaking, LED light assembly and electronic device assembly. Such work is usually undertaken at the platform worker’s home or at a private office. The worker accepts the task and the materials are then shipped to the worker who assembles the products and returns them when completed, usually by mail, to the client. Typically the craft and assembly work has a unit price that is determined by the client. This work is essentially industrial outwork, but it is mediated through a digital labour platform.

The sheer size of China’s platform economy makes it difficult to make any broad generalizations. With over 400 platforms and 50 million registered platform workers in 2010 (iResearh, 2010), the Chinese labour platform landscape is heterogeneous, with new jobs posted continuously. The market competition has been keen and around 100 platforms survived at 2015; meanwhile, the number of platform workers is estimated to have has increased to over 30 million (Li and Wang, 2015). The selection of work available on large platforms is particularly diverse and can range from clients seeking someone to produce simple handicrafts, to highly technical tasks in the fields of IT development and cloud technology. From our research on the distribution of tasks available on three major online Chinese platforms (ZBJ.com, EPWK.com and 680.com), some of the most popular categories of work include logo and web design, promotion and marketing, IT and software development, property and patent services, business and taxation services, and computer game development.

In online and location-based work, the terms and conditions of work are outlined by platforms in their respective “terms of service” documents. These are often long and dense text documents that function as a type of contract and can be difficult for individuals without legal training to understand. Nonetheless, workers must accept a platform’s terms of service in order to begin working. Such documents vary by platform but typically govern issues such as how and when platform workers will be paid, how work will be evaluated, and what recourse workers have (or do not have) when things go wrong. Like digital labour platforms in other countries, terms of service documents for Chinese platforms typically treat platform workers as “self-employed”. For example, on the platform ZBJ.com, the exchange of work for a wage is regarded as a commercial exchange rather than an employment contract.4 By virtue of their self-employed status, platform workers are thus excluded from many labour protections and social welfare provisions, which can be a cause for concern given the possibility that these can adversely affect working conditions.

China’s state-run public media has promoted platform work as a flexible employment opportunity capable of providing a potentially good source of income. For example, in 2009 during the early stage of platform development, a TV program reported that home-based mother had earned between 4 and 5 thousand Yuan per month at for her work as a Witkey designer. This reporting emphasized the attractive earning opportunities on platforms, which were on par with (and sometimes exceeded) the average income of Beijing employees, which at the time hovered around 4000 RMB (People’s Republic of China, 2010).5 Such advertising has continued to propel the growth of the platform economy in China. As a result of the enabling economic and political environment, the number of Chinese platforms has steadily increased since 2005 and, although there are no comprehensive statistics, the same is likely true of the number of workers on platforms.

For platform companies, the market has become increasingly competitive and there have been many new entrants. K68.cn, China’s first platform, continues to be a dominant market player and is listed as one of the top 50 brands (BRAND 50) in China’s internet market.6 But new competitors have also entered the market and have gained significant traction. For example, the “ZhuBajie network” (herein ZBJ.com,) based in Chongqing, received a 5 million RMB investment in 2007; this venture capital proved sufficient for ZBJ.com to expand its business. Then in June 2015, ZBJ.com received another 2.6 Billion RMB of venture capital, the most significant investment of any online platform market in China at that time. This vast investment and growth eventually led ZBJ.com to become the Chinese platform with the highest volume of internet traffic.

Since ZBJ.com has assumed a dominant market position, it has changed its fee charging structures. The platform has stopped charging workers a 20 per cent transaction commission (交易佣金) for use of the platform and it has ceased charging fees to customers. Instead, ZBJ.com has elected to subsidize both sides of the market using venture funding to help the platform gain an even larger market share, perhaps in a bid to become the dominant market player. In other markets, subsidies have proven an effective way to bring on board new workers and customers, as subsidies bolster workers’ incomes and reduce customers’ costs; this strategy appears to be working in China as well. In a case study report published by Remin University’s School of Journalism found that as of the end of 2014, ZBJ.com had attracted over 11 million clients and over 12 million workers. This resulted in more than 5.3 billion RMB worth of transactions on the platform and accounted for a market share of over 80 per cent (Li and Wang, 2015: section 3 and figure 4). But importantly, the rise of ZBJ.com suggests that in China, the online platform market may be characterized as an oligopoly, with only a few dominant players dictating market conditions. These firms, in turn, have the potential to influence economic relationships throughout the supply chain.

While platform earnings and user numbers remain proprietary, efforts such as the Oxford Internet Institute’s Online Labour Index have shown how the volume of online visits to a platform can be used as a proxy for a platform’s popularity and potentially shed light on its market share. For Chinese platforms, we have examined the search engine rankings from two different sources. The first source come from Baidu, China’s most popular search engine. The first figure is the

As of 2020 the rankings of China’s four largest platforms were as follows:

-

zbj.com (猪八戒威客网)

Baidu weight: 7, ALEXA PV ranking: 4,651 and ALEXA UV ranking: 5,438.

-

epwk.com (一品威客网)

Baidu weight: 6, ALEXA PV ranking: 811 and ALEXA UV ranking: 963.

-

680.com (时间财富网)

Baidu weight: 8, ALEXA PV ranking: 14,367 and ALEXA UV ranking: 15,064.

-

k68.cn (K68威客网)

Baidu weight: 3, ALEXA PV ranking: 1,116,890 and ALEXA UV ranking: 1,492,697.

Survey design and research methods

2.1 Platform selection

With a view to better understanding how digital labour platforms function in China and the experiences of workers on these platforms, the ILO has adapted an online survey previously run on other labour platforms and countries (Berg, 2016; Berg et al., 2018; Aleksynska et al., 2018) to the Chinese context. The survey was administered to workers on the country’s top three online platforms as determined by their Alexa ranking and Baidu weight: ZBJ.com, EWPK.com, and 680.com. These platforms offer a wide range of tasks and are appealing to workers with different professional backgrounds.

-

ZBJ.com (猪八戒威客网) was established in 2006 with headquarters in Chongqing City. The platform provides users with a one-stop, well-rounded corporate service platform capable of meeting the needs of corporate clients. It received three rounds of venture capital investment funding, including a third (C round) cycle that amounted to 2.6 billion, before it was listed on the stock market. Major investors included Cyber Group (赛伯乐集团) and Chongqing State-Owned Enterprises (重庆国有企业). ZBJ.com is currently the largest online aggregated labour platform in China, where it covers six industry categories including brand creativity, product/manufacturing, software development, corporate management, corporate marketing, and personal life services, with a total of more than 600 different job and task categories listed on the platform.

-

The second platform surveyed, EPWK.com (一品威客网) was established in July 2010 with headquarters in Xiamen City, Fujian Province. It has received three rounds of venture capital investments amounting to 170 million of yuan. The third round of investment was 100 million yuan in August 2018 and was the largest investment among the three, which was led by the Shun Heng Fund (顺恒基金).9 The platform provides a one-stop crowdsourcing service to enterprises offering an array of services, including more than 300 types of tasks in seven industry categories: design (logo, animation, industrial), development (website/software), decoration, copywriting, marketing/promotion, business services (registration, trademark/copyright, taxations). As of 2018, the platform’s daily average announced jobs on creative designs and R&D is over 5000 and its’ cumulated transaction volume is over 12 billion Yuan.10 Therefore, it can be considered as one of the largest competitors for the ZBJ.com.

-

680.com (时间财富网) was the third platform included in this research. It was initially established in September 2006 under the name vikecn.com (威客中国) with headquarters in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. Information on the company’s financing and investments is not publicly available, but the platform offers services similar to those mentioned above including: business services (registration, copywriting, tax, planning), creative design (logo, animation, package, visual), development (website construction, software programming), architectural/industrial design, marketing/promotion and other fields.

2.2 Survey methodology

A crucial advantage of doing an online survey of online platform workers is that platforms require registration and membership in order to work, which can thus be used as a survey recruitment tool and a mechanism to validate that the respondents are indeed platform workers. On each of the three platforms identified, respondents were recruited by posting a link to the survey as a paid ‘task’ on the platform. Workers who met the eligibility criteria of being at least 18 years old and having done platform work for at least three months, could then accept the task. Once the task was accepted, respondents were referred to popular online survey platform, wenjuanxing (问卷星, in English “survey star”)11, where they were able to complete the survey. The three-month tenure requirement was introduced as a way to ensure that respondents had a basic understanding and work experience and could thus provide meaningful responses. This eligibility requirement was also used in other ILO platform worker surveys. Upon completion, workers received 20 Yuan, and after responses were collected and the data were cleaned, there were a total of 1,071 respondents.

The data cleaning process was rigorous and comprehensive. To control for spam and multiple entries, we placed restrictions on respondents IP addresses on both the labour platform and the wenjuanxing survey site. This allowed us to ensure that the survey was only completed once from a particular internet connection site (a proxy for ensuring that the survey was completed no more than once by any given individual). We also developed a rigorous checklist with cross-checking questions to ensure the validity of the survey responses. For example, to detect random responses, we added a fake platform name in the question of “platform worked before.” To control for inconsistent responses, we cross-checked questions about workers’ work, identity, and income to ensure a logical relationship among variables, such as the total average income had to be bigger or equal to the income generated from the platform. A cleaning rule was imposed: whenever two inconsistencies were observed, the respondent would be dropped from the sample. If there was only error, then the survey responses were retained; however, we omitted these outliers in the analysis whenever appropriate. After cleaning the data, we confirmed 1,071 surveys (of the total 1,174 received) as valid, with the following distribution by platform:

Table 1. Surveyed platforms and the distribution of respondents

|

Platform |

Freq. |

Percentage |

Cum. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

680.com |

300 |

28.01 |

28.01 |

|

EPWK.com |

233 |

21.76 |

49.77 |

|

ZBJ.com |

538 |

50.23 |

100 |

|

Total |

1,071 |

100 |

It is important to bear in mind when analyzing the results of the survey, that we do not know whether the respondents who completed the questionnaire constitute a statistically representative sample of platform workers. As there is no universal database of platform workers, it is not possible to draw a random sample. Some workers may be less inclined to accept work that includes filling out questionnaires; if this characteristic is associated systematically with other attributes, then the sample may be skewed. However, in the absence of publically available administrative data, the choice to post the survey as a task constitutes the only possible way of gleaning information on the working conditions of online platform workers. The previous ILO studies (Berg, 2016; Berg et al, 2018; Aleksynska et al., 2018) followed a similar methodology and thus suffer from the same possible shortcomings.

The sample of workers in Aleksynska et al. (2018) on digital platforms in Ukraine are likely to be more similar to the China survey as this survey covered 1,000 Ukranian workers who worked on a range of platforms, both national, regional and international, involving both high-skilled IT programming work to less-skilled “microtask” work. Berg (2016) and Berg et al. (2018), on the other hand, covered workers only on microtask platforms. The sample covered workers living in 75 countries working on five English-language microtask platforms, with a strong representation of workers from India and the United States.12 While there is microtask work on the Chinese platforms, the variety of jobs available is much wider, requiring a broader skill set and likely allowing for greater relative compensation.

2.3 Survey content overview

Like previous ILO surveys, data were collected on working conditions, including pay rates; working time and availability of work; work intensity; rejections, non-payment and fraud; worker communication with clients and platform operators; social protection coverage and the types of work performed. Though adopted to the Chinese context, significant efforts were made to ensure that data collected from China would be as comparable as possible to data collected on other labour platforms previously surveyed by ILO.

The survey was divided into seven sections, covering the following topics: (1) socio-demographic information; (2) platform work employment; (3) relations with the client on the platform; (4) other current jobs; (5) pre-platform work employment; (6) financial situation; and (7) current platform situation and future development expectations.

Overall the survey consisted of approximately 85 questions (follow up questions excluded) and took respondents on average approximately 30 minutes to complete. For the primary set of questions, respondents were typically asked to choose from available responses; however, the survey also included follow up questions for the purpose of allowing workers to provide more detail about their particular experiences. Such follow up questions were often structured so that respondents could provide open text answers.

The three selected platforms for research in the Chinese context offer a wide variety of jobs ranging from high to low skilled work, and in this respect, are very similar.13 Workers were asked to indicate the types of tasks they engage in on platforms from a list of possible responses. These included high-skilled, online platform work in fields such as IT, design, video production, editing and writing, and online education. We also included a range of possible responses that captured jobs requiring lower levels of skill such as sales and promotions, customer service support, filling in opinion polls and questionnaires, microtasking (short, clerical tasks to ensure smooth functioning of web services and other business activities) and “online order outsourcing manual works” which encompass the craft and assembly work described above (网上在线下单,外发手工活). While the list was comprehensive, we elected to exclude work that is dispersed online but conducted offline in other spaces (线下兼职), such as transportation or delivery workers, as well as vacancies that are merely advertised online.

Survey findings

3.1 Socio-demographic information and job tenure

The survey began with a section that collected socio-demographic information about survey respondents. Our findings reveal that within China, online platform work has much higher rates of male participation. Overall, only 30 per cent of all workers are female; however, these rates vary slightly depending on the platform (27 per cent of ZBJ.com workers are female compared to 37 per cent of workers on 680.com and 32 per cent in EPWK.com). This gender distribution is similar to findings from other surveys, including of Indian workers on the Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) microtasking platform, where 31 per cent were women. However, rates of female participation on Chinese platforms are considerably lower than the rates observed in industrialized countries or in Ukraine (48 per cent were women).

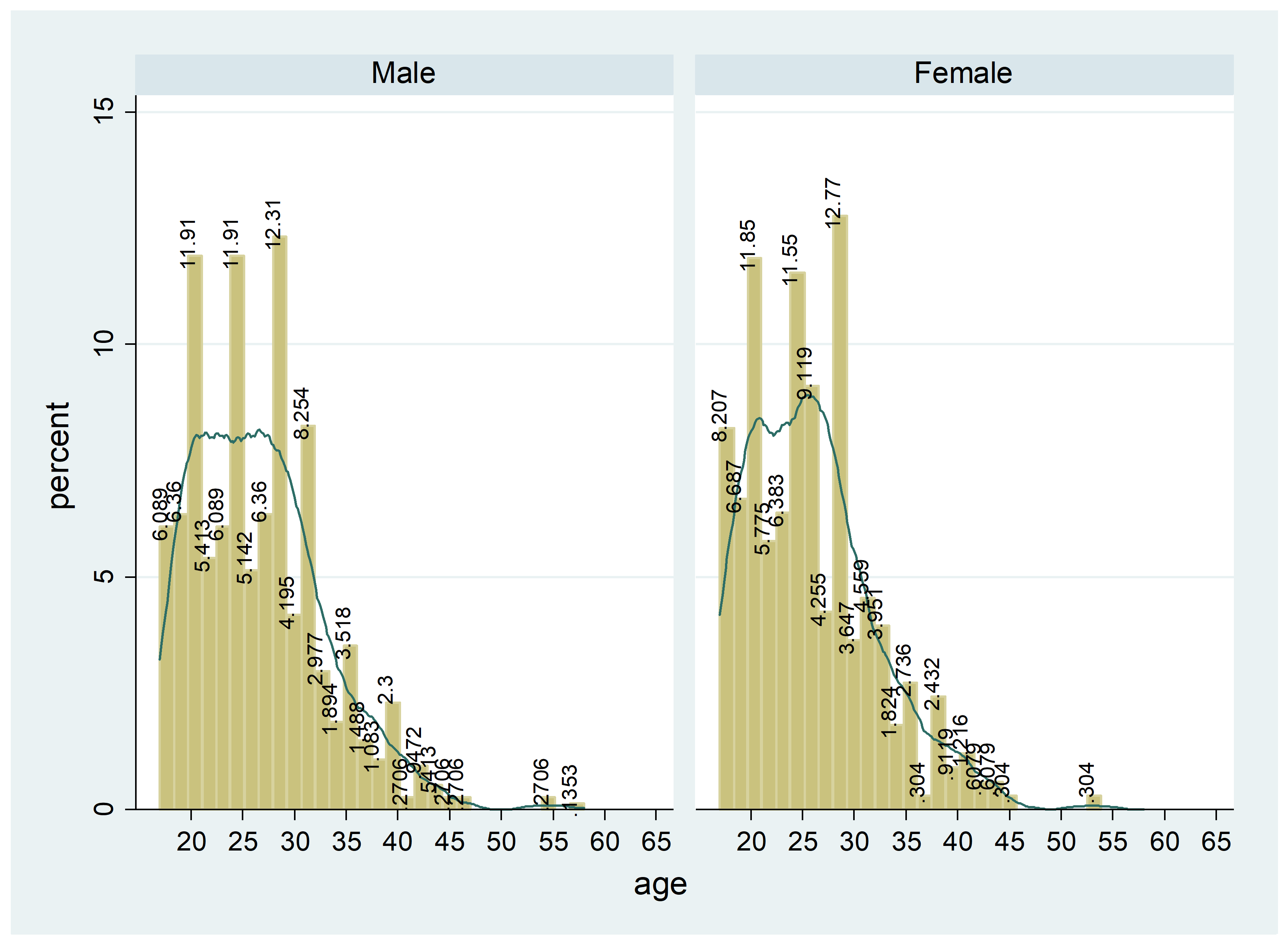

On average Chinese workers are between 25 and 27 years old, making them slightly younger than the average age of workers from developing countries working on microtask platforms (28 years), and several years younger than the Ukranian platform workers (33 years) or the average age of industrialized country workers on microtask platforms (35 years) (Berg et al., 2018; Aleksynska et al., 2018). Figure 1 gives the age distribution by gender, revealing consistency between women and men.

Figure 1. Age distribution by gender

Given that Chinese platform workers tend to be young, we would expect that a higher proportion of respondents were unmarried, and indeed, we found this to be true. Overall 59.6 per cent of platform workers identified themselves as unmarried with ZBJ.com having the lowest rate (56.7 per cent), and EPWK.com the highest (64.4 per cent).14

Despite a minority of workers being married, a majority of workers had members of their household who were financially dependent on them (55.9 per cent). When asked for details about the family support they provided to household members, 34.9 per cent indicated they help to take care of at least one child in their household. Most of these children were aged six or below (24.6 per cent), while children between 7 and 12 years old and those between 13 to 18 years old accounted for fewer cases (9.7 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively). Caring for adult family members who resided in the household was the most common form of support provided and accounted for 38.5 per cent of all respondents.

It was also quite common for platform workers to care for dependents who resided outside of the household, with 40 per cent of respondents indicating they had such responsibilities. Again, caring for adults proved to be the most common obligation (33.8 per cent) followed by children under six (7 per cent) and children between 7 and 12, and 13 and 19 (3.3 per cent and 3.5 per cent). While workers tended to financially support individuals with whom they resided at higher rates than those who lived apart, providing financial support for individuals who were living outside of the immediate household, was still significant. 15 More often, this person was an adult. The findings of the survey coincide with the findings from existing research on family structure in China, which finds that young workers are financially supporting older generations in particular. In these cases, although extended family members are not living together, “respondents still need to share the burdens of these dependents […] who are independently living outside of the family or with their own ‘nuclear family’”.16

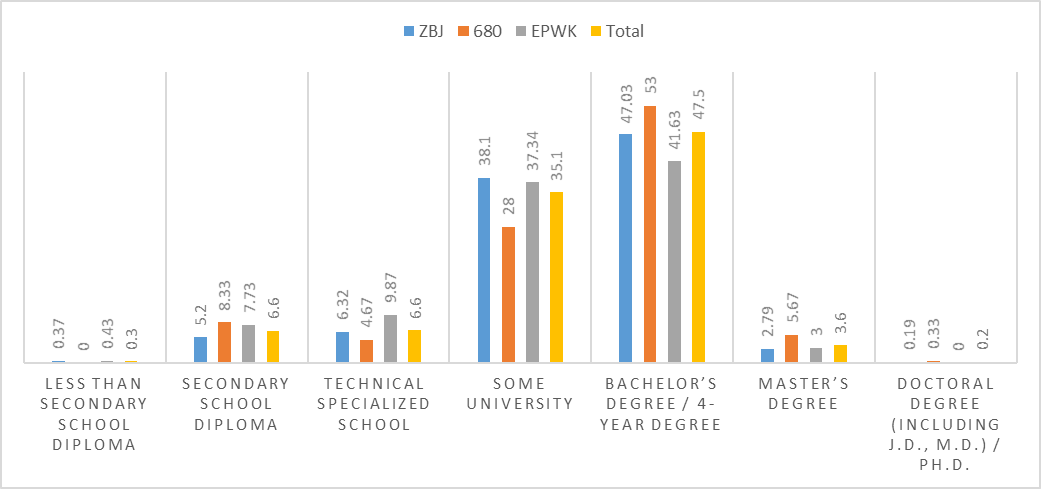

When it comes to education levels, the vast majority of platform workers in China have finished some university education or have received a Bachelor’s degree. When asked about the highest level of education they had completed, 0.28 per cent of respondents reported having completed “less than secondary school”; 6.6 per cent have finished “secondary school,” and another 6.6 per cent indicated they had a “technical specialized school” level of education. Much larger percentages of workers completed “some university education,” (35.1 per cent), and 47.5 per cent have finished the Bachelor’s (or 4-year college) degree. A smaller proportion, 3.8 per cent of respondents, had a Master’s degree or above.

In China, as in the previous surveys conducted by the ILO of platform workers, workers are well educated, reflecting both the need to be digitally literate in order to work on the platform, but also the range of skills required for some of the work available on the platforms. In the survey of microtask platform workers — which has a lower skill requirement than other types of online platform work — the workers were also well educated. Among American workers on the AMT platform, 44 per cent had a completed bachelor’s or master’s degree and 39.8 per cent had some university education. Indian workers were the best educated, with 91.3 per cent having either a bachelor’s degree or master’s/Ph.D. In the study of Ukranian platform workers, 73 per cent of the workers had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Yet despite the high level of education of the Chinese platform workers, 54 per cent reported that they would need further technical training to complete all of the tasks on the platform. Only 28 per cent responded that their skill levels correspond well to the demands of the platform; 9 per cent indicated that they have skills levels to do more demanding tasks than what is available on the platform. This finding may be reflected of the wide variety of tasks that are available on the Chinese platforms, but it could also reflect the high percentage of respondents who identified as students (22 per cent).

Figure 2. Educational level by category (percentage by category)

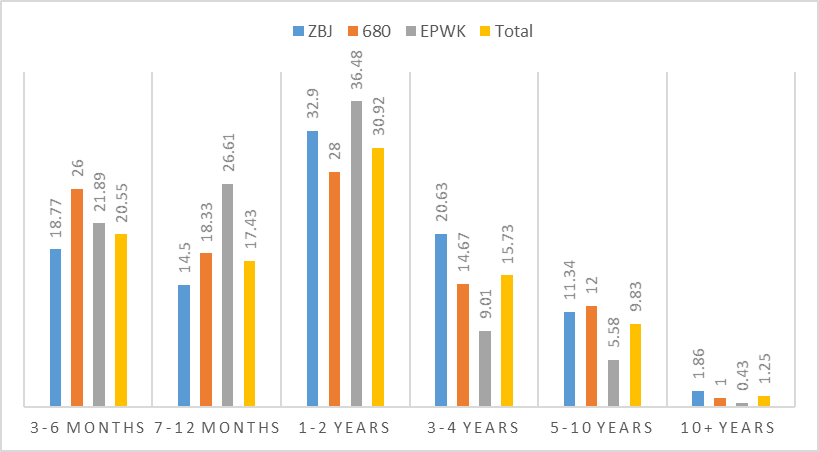

When it comes to job tenure among platform workers in China, the distribution is reasonably consistent across the platforms surveyed. Sixty-two per cent of respondents had more than one year of experience as seen below in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Tenure of survey respondents (percentage by category)

The most considerable variations between the three surveyed platforms is with reference to EPWK.com, which has a larger proportions of its workers who have been active between 7 months and 2 years, and fewer workers active in the 3-4 and 5-10 year range compared to ZBJ.com and 680.com.

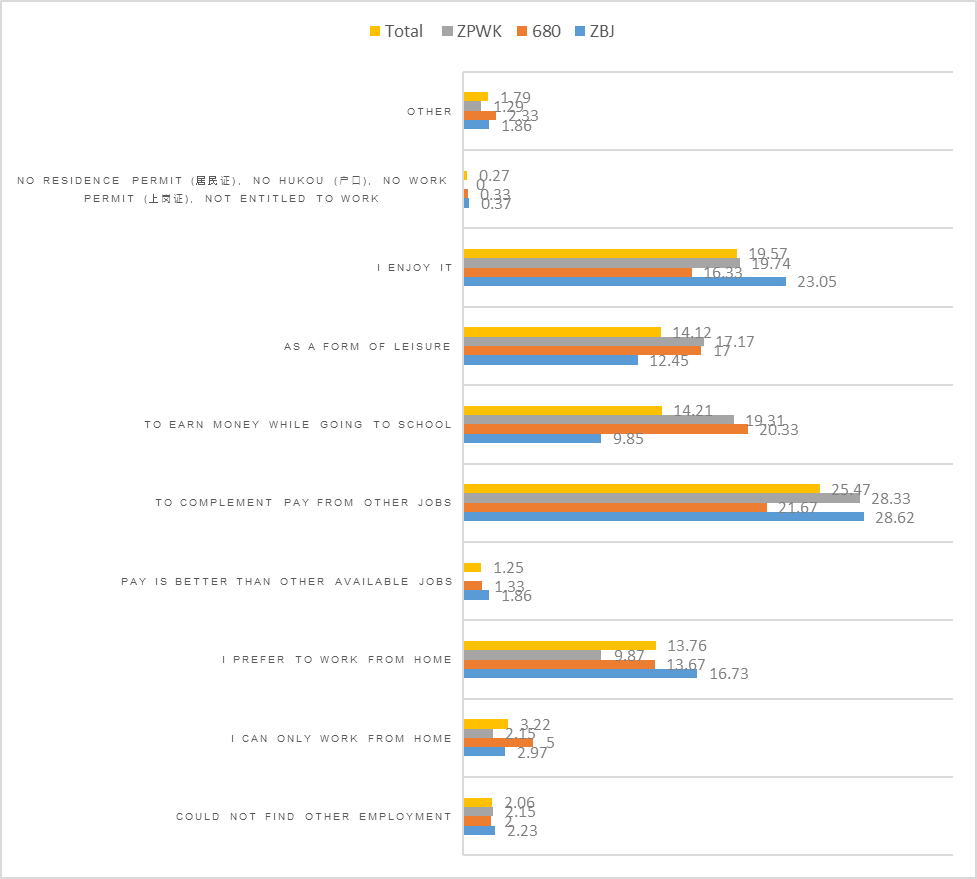

The survey contained various questions which could help to shed light on the patterns we see above regarding tenure. Influential factors, for example, might be understood in light of the question on the most important reasons that workers engage in platform work, the responses to which are included below in Figure 4. Based on the reasons people give for engaging in platform work, those who work on ZBJ.com platform are less likely to do so in order “to earn money while going to school” (9.85 per cent). Unlike 680.com and EPWK.com, this suggests that ZBJ.com may be a platform that tends to attract workers who are in search of a longer-term work prospects and not students looking for a short-term earning opportunity and who we might expect to have higher turnover, in the order of 0-4 years, as we see in the case of EPWK.com above in Figure 3. EPWK.com is also the youngest of the three platforms, which could also have an impact on this distribution.

Figure 4. Most important reason for doing online platform work (percentage)

Platform specialization may also explain the differences in the tenure of platform workers affiliated with these two firms. Our survey findings reveal that ZBJ.com has a higher percentage of tasks classified as ‘high skill’ relative to EPWK.com. As was explained earlier, though education and skills are not synonymous, there is usually a strong correlation between the two. These findings, described in greater detail in the subsequent sections, note that ZBJ.com has a greater percentage of tasks in the fields of IT (software and web programming) and design and photo processing and may incentivize workers to stay on the platform. On the other hand, EPWK.com has higher percentage of lower-skilled tasks such as filling in opinion polls and questionnaires, official sales and promotion tasks, and customer services and reviews which could be seen as less desirable for the mid and long term. Percentages are included in Table 4, which highlights the distribution of platform jobs by platform surveyed.

3.2 Workers' current main occupation: Do they have other jobs?

The survey seeks to understand the role that platform work plays as a component of workers livelihoods. The majority of workers (79.1 per cent) obtain their primary income from a source other than platform work. Related findings indicate nearly two-thirds of respondents (64 per cent) have another paid job (with 36 per cent reporting that they do not).

Respondents were asked about their main occupation. In line with the previous finding that one-third of the sample did not rely on any other paid jobs (or businesses) besides platform work, 21.9 per cent of respondents indicated that they were students, 9.4 per cent indicated that they only did platform work, and 4.1 per cent were involved in offline platform work, such as Didi drivers or app delivery workers. The rest of the respondents indicated other occupations with the largest share constituted by professional and technical personnel in enterprises and institutions (21.4 per cent), followed by 12.3 per cent engaged in business and service industries.

Table 2. Workers’ main occupation distribution (percentage)

|

Occupation |

Percentage |

|---|---|

|

Party and state organs, enterprises and institutions responsible persons |

2.2 |

|

A business owner with officially registered companies and employees |

5.0 |

|

Professional and technical personnel in enterprises and institutions |

21.4 |

|

Administrative staff in enterprises and institutions |

8.9 |

|

Workers engaged in business and service industries |

12.3 |

|

Personnel engaged in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, water conservation |

1.3 |

|

Workers engaged in production and transportation in the enterprise |

3.8 |

|

Military |

0.1 |

|

Student |

21.9 |

|

Local platform work, such as: DiDi, takeaway, etc. |

4.1 |

|

No work other than online platform work |

9.4 |

|

Working in other categories (please specify) |

9.5 |

|

Total observations |

1,071 |

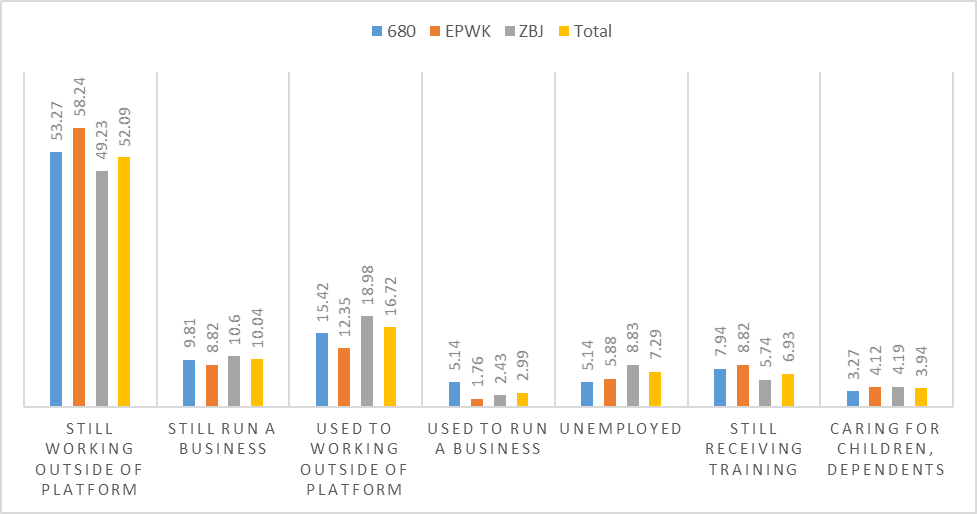

The survey asked workers about the job they held immediately before starting to work for digital labour platforms. Results indicate that the largest share of respondents (52.1 per cent of total) had a job outside of an online platform before they began platform work and still have this job; a smaller portion of platform workers (10 per cent) had previously run and are still running a business. This means that over 60 per cent (62.1 per cent) of total workers have retained the same income source they had before beginning to work on labour platforms and have thus added platform work to their income-earning activities. This figure is similar to the survey results of Ukranian platform workers, which found that two-thirds of workers had jobs in the offline economy in addition to platform work (Aleksynksa et al., 2018).

Fewer people used to work outside of labour platforms and have left their job (16.7 per cent of respondents), and, as can be seen in Figure 5 below, a significantly smaller 2.99 per cent of respondents were running a business that no longer exists.

There is often an argument in China and elsewhere that platform work could help the unemployed to reenter the labour market. Platforms could provide access to (temporary) jobs that workers could use to supplement their incomes, while providing them with working time freedom. Our survey allows us to determine whether, in the context of China, platforms have fulfilled this promise. Our survey included 61 workers who identified that they were unemployed before they began working on platforms, comprising a total of 7.3 per cent of survey respondents. This rate is much lower than the one-third per cent of respondents surveyed on the western microtask platforms that reported being unemployed prior to engaging in platform work (Berg et al., 2018). Additionally, 6.9 per cent of Chinese respondents said that they were “still in education or training”, and 4 per cent indicated that they had previously been caring for children.

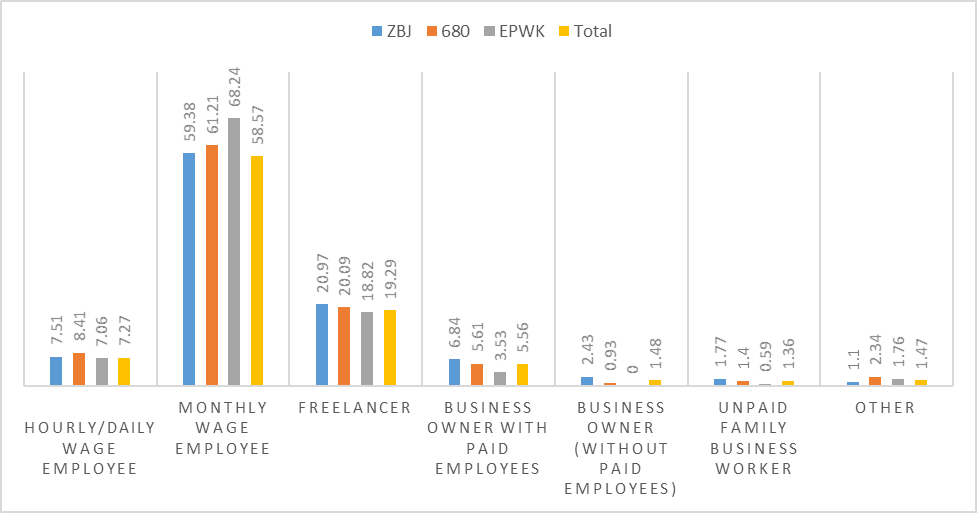

Figure 5. Work activities prior to engaging in platform work (percentage)

For workers who work outside of their platform work, most are waged employees who receive income monthly (58.6 per cent). There are, however, a surprisingly large proportion of freelancers (19.3 per cent), with the third most common response indicated as “hourly/daily wage employee” (7.3 per cent).17 The high proportion of freelancers and hourly/daily wage workers, which accounts for more than one in four, implies that many platform workers may be used to non-standard forms of employment. This could cause individuals to view some of the less desirable conditions associated with platform work, such as variable incomes and working hours, as fairly normal. (See Figure 6).

Figure 6. Job or business where you spend most time outside of platform work (percentage)

Among those who have a job outside of the platform economy, a majority (54.84 per cent) have completed platform tasks while at their other jobs at an average rate of 7.8 hours per week. Of the three platforms surveyed, this practice is most prevalent among EPWK.com workers, 60 per cent of whom report doing this. As in the other surveys, we asked whether the workers believed that their bosses would be opposed to them using working hours to engage in platform related tasks. Over 40 per cent (44.9 per cent) of those who responded indicated that they felt their boss would be accepting of this use of time.

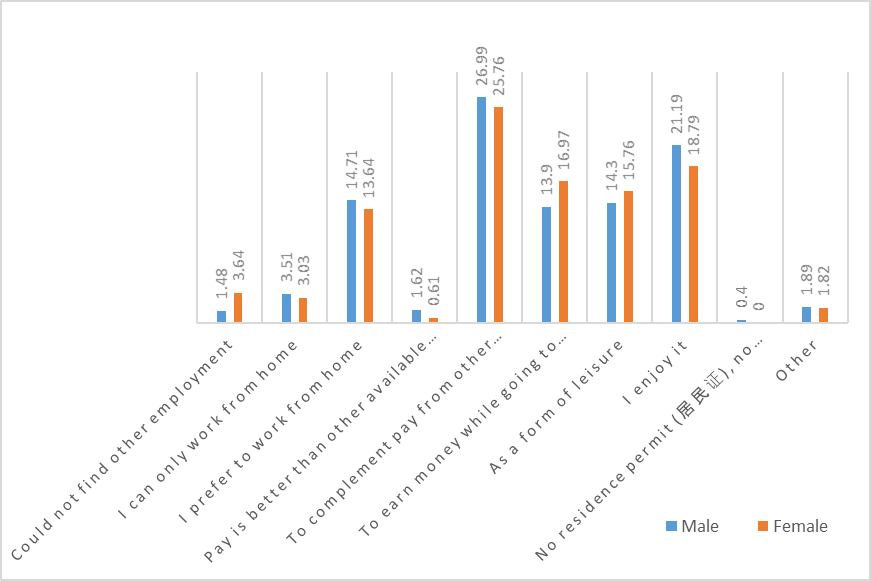

3.3 Motivation to engage in online platform work

Given that a significant proportion of respondents do platform work in addition to having another occupation, it is not surprising that the single most common reason that people worked on digital labour platforms was to “to complement pay with other jobs” (25.5 per cent). Many workers also seem to engage in platform work because they liked it. The related responses of doing platform work were because they enjoyed it (19.6 per cent), and because they felt it was a form of leisure (14.1 per cent) both garnered high response rates. A sizeable proportion of Chinese workers also preferred to work from home (13.8), and given the high proportion of students on these platforms, it was unsurprising that another 14.3 per cent did online platform work to earn money while going to school. Doing platform work to complement other income sources is also consistent with results from the ILO’s survey of microtask workers, which found that one-third of workers engaged in microtask work to complement their pay from other jobs, and 22 per cent did it because they preferred to work from home (Berg et al., 2018).

The high rates with which workers report doing platform work for enjoyment and leisure is further contextualized by the fact that a minority of platform workers work online as their main source of income. This may allow them greater freedom and an ability to work as they choose. The total weekly working hours spent on platform work (including both paid and unpaid hours) for the workers who do platform works “as a leisure” is 19.4 hours, lower than the average number total working hours which hovers at 23.9 hours.

In some developing countries, platform work has been promoted as a mechanism to expand job prospects to those who might not otherwise have them (Graham et al., 2017). In China, since industrialization, urban centres have been associated with more vibrant labour market opportunities; rural areas, meanwhile have maintained a strong agricultural focus. To help control internal employment related migration, China came to rely on a household registration system, hukou, to prevent rural populations that faced more limited labour market prospects, from migrating to urban centers and competing with urban resident (see Chan, 2013). Under this system, agricultural hukou holders who relocated to urban areas faced distinctive challenges. They could not, for example enroll their children in urban schools, and in the job market they experienced higher levels of employment precarity. Approximately one-fourth (23.6 per cent) of our data sample was comprised of rural to urban migrants who could face such challenges. The structure of online labour platform work, however, reveals that not having a local resident card, hukou, or working permit (0.27 per cent) is not a motivation for undertaking platform works. Furthermore, these online platforms might even be offering those in rural areas expanded employment opportunities, in particular for the 8.1 per cent of respondents who identify as rural residents.

The most significant divergence in the findings from the Chinese survey and the ILO survey of microtask workers was related to the percentage of workers who can only work from home. In China, this figure accounted for only 3.2 per cent of respondents, compared to approximately 8 per cent in the microtask survey. Various factors could account for this difference. In China, respondents are relatively younger in age and a lower percentage are married workers (40.4 per cent of total), suggesting that they may have fewer family responsibilities that require them to stay at home. Among this relatively small proportion of workers, however, our findings do reveal that caretaking reasonability’s tend to be gendered. In China, the breakdown of male and female respondents who could only work from home was 3.5 per cent of men (26 observations) and 3 per cent of women (10 observations).18 However, only six out of the 26 male respondents could only work from home because they were “taking care of family, elderly, or children” while five responded that they have “sickness or disability.” Among women, meanwhile, seven out of the ten attributed their ability to work only from home to their caretaking responsibilities. (See Figure 7).

The comparability of platform work to other labour market opportunities is a less important motivator for respondents. As seen above in Figure 5, only 1.25 per cent of respondents indicated that the “pay is better than other available jobs”. While this was similar to the percentage of American AMT workers who responded accordingly (1 per cent) it was much lower than the 18 per cent of Indian AMT workers who indicated that online platforms provided better pay than other available jobs. The difference between Indian and Chinese workers highlights important differences between these two developing countries with respect to the national average wages. The minimum wage standard and the average wage in China, although, are not as high as those in America, are much higher than in India. Another important factor could be the client market. Indian workers on international platforms like AMT and Crowdflower may be meeting the needs of an international clientele who may be paying rates that, while insufficient for most Western workers, are comparatively good in the Indian context. Chinese platforms, on the other hand, meet domestic market needs where clients may be better attuned to the local reservation wage.

Figure 7. Most important reason why you do platform work

3.4 Platform work employment: On which platforms do they mostly work?

Multihoming, or working on multiple platforms simultaneously, is a well-documented phenomenon in platform work (Choudary, 2018). Respondents were asked about how many platforms they worked on in the month preceding the survey; one-third indicated that they only worked on one platform, 30 per cent worked on two platforms, and 18.9 per cent worked on three platforms. This suggests that workers tend to concentrate their online work on a select number of platforms. Our findings also reveal that in general, the survey reached workers on the platform on which they were most active. For example, and with reference to Table 3 below, of the 536 workers interviewed on ZBJ.com, 74.4 per cent indicated that they were most active on ZBJ.com while 73.3 per cent of EPWK.com workers were most active on that platform. Indeed, as the country’s most popular platform, ZBJ.com was the most commonly used platform across our sample. Of the three platforms surveyed, workers who were recruited through 680.com were least likely to use that platform as their primary one.

Table 3. The platform on which workers worked most of their time during the past 3 months (percentage)

|

Platforms worked |

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Freelancer.cn |

3.3 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

|

zbj.com |

6.3 |

12.1 |

74.4 |

41.8 |

|

Epwk.com |

9.7 |

73.3 |

9.9 |

23.6 |

|

680.com |

64.3 |

3.0 |

1.5 |

19.5 |

|

k68.cn |

7.0 |

3.9 |

1.9 |

3.8 |

|

Others |

9.3 |

4.3 |

9.1 |

8.2 |

|

Total observations |

300 |

232 |

536 |

1,068 |

3.5 Types of work undertaken on platforms

Prior to conducting this survey, our literature review of Chinese labour platforms revealed many types of work available on platforms. Our survey results confirmed this. Our data, seen below in Table 4, reveal a wide distribution of platform tasks, but we find that the most popular tasks are the same for the three platforms surveyed.19 According to the total respondent distribution (in parenthesis), and to this distribution on each individual platform, the top four tasks related to “design and related photo processing” (23.6 per cent), “Filling in opinion polls and questionnaires” (17.5 per cent), “IT (software and web programming)” (14 per cent), “Editing/writing services/code typing” (10.3 per cent). “Filling in opinion polls and questionnaires” was also a popular selection, though high levels or reporting in this category could have also been influenced by the fact that our survey was emblematic of this type of work.

Table 4. Distribution of major platform work industry (percentage)

|

|

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No answer |

7.7 |

8.2 |

7.1 |

7.5 |

|

IT (software and web programming) |

|

|

|

|

|

Design and related photo processing |

|

|

|

|

|

Film and television production/related services |

3.0 |

6.9 |

3.7 |

4.2 |

|

Translation services and related works |

4.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

2.0 |

|

Editing/writing services/code typing |

|

|

|

|

|

Official Sales and promotions |

5.0 |

6.0 |

3.0 |

4.2 |

|

Customer services and reviews |

7.0 |

3.0 |

1.9 |

3.6 |

|

Filling in opinion polls and questionnaires |

|

|

|

|

|

Other consultancy (such as legal services) |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

Online education, tutoring, and related works |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

Microtasking (filling in data into spreadsheets, etc.) |

8.7 |

8.6 |

5.8 |

7.2 |

|

Online order outsourcing manual works |

0 |

0 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

|

Other |

1.7 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

|

Total observations |

300 |

233 |

538 |

1,071 |

ZBJ.com appears to have tasks that are associated with slightly higher skills compared to the other two platforms. This can be seen most clearly vis-à-vis IT and design work, where the rates of these types of tasks are reported with greater frequency on the order of 5-10 per cent. Conversely, survey work and microtask work, which tends to be associated with lower skill requirements, are more common on 680.com and EPWK.com. This distribution comparison shows that although the major task type distributions are consistent among platform (suggesting the platforms respond to similar client needs) platforms appear to have slightly different specializations. Distinctions between the platforms regarding task type may also be a function of the platforms’ business model, particularly with reference to their respective memberships and fee-charging systems.

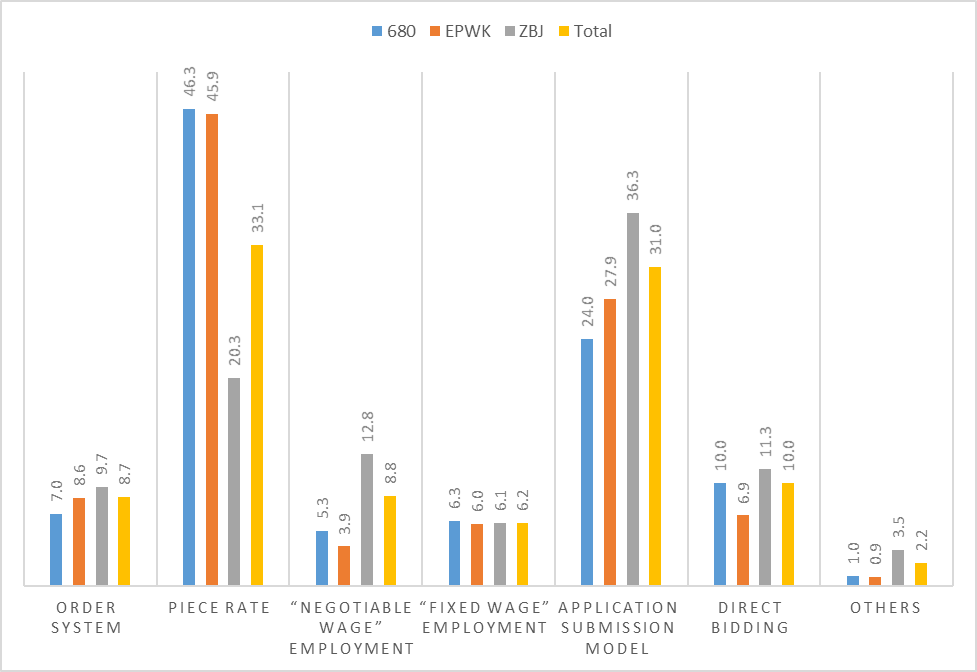

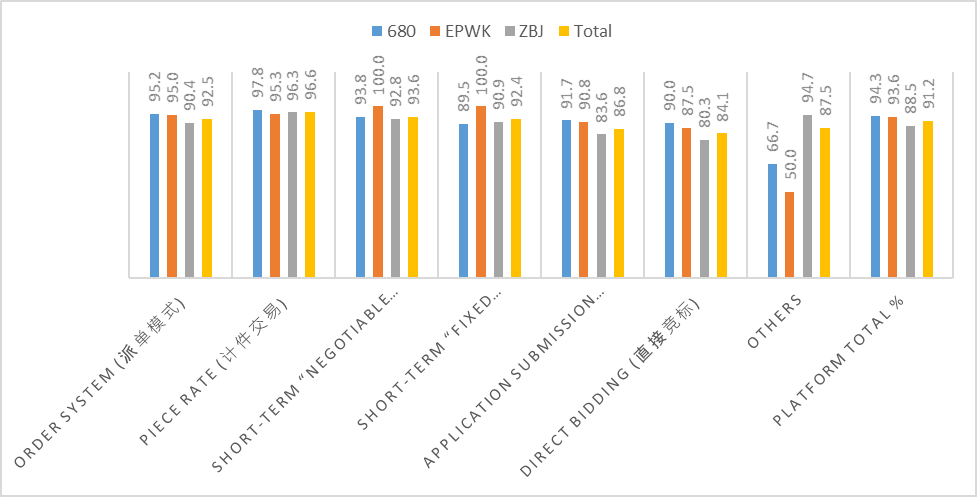

Chinese platforms often incorporate various models for task distribution and payment structures. Our survey identified seven different ways that tasks are distributed, and asked respondents to respond to indicate the distribution mechanism that they most often experience. Possible responses included: Order system (派单模式); Piece rate (计件交易); Short-term “negotiable wage” employment (短期议价雇佣); Short-term “fixed wage” employment (短期固定薪金雇佣); Application submission model (报名, 等待甄选模式); Direct Bidding (直接竞标); and other. Each of these categories were defined in the survey to ensure that respondents could correctly identify the competition model most commonly associated with the work that they did. For example, piece rate (计件交易) was defined as “demanders announce the needs (quantity and quality) and service providers produce the final products within the time limit”. Direct bidding, meanwhile was indicated by “after the demand side announce the needs and budgets, qualified developers grab the project as soon as they can. This model depends solely on the qualified developers’ speed of grabbing the bid offered by the customers”. Full definitions for each of these categories can be found in Appendix 2.

From these possible responses, “piece rate” (33.14 per cent) and “application and submission” (31 per cent) accounted for almost two thirds of all responses. However, significant differences existed between platforms that were reflective of each platform’s specialisation. For example, one-fifth per cent of ZBJ.com respondents indicated that they were paid by the piece, while about 45 per cent of workers on the other platforms typically worked according to the piece-rate model. “Application and submission”, meanwhile was the most common on ZBJ.com at a rate of 36.25 per cent. In this type of work, customers announce a project’s price and their needs and workers supply their CVs and proposals within a given time limit. This type of model can also take the form of a competition or a competitive presentation, and is particularly common on design platforms in western countries, such as 99design. This type of model was less common on the other platforms. (See Figure 8).

Figure 8. Task allocation and payment method most typically used by respondents by platform (percentage)

The type of model has implications on the payment structure that workers confront, specifically the fees they are charged and the need to buy membership.

3.6 Membership and fees in China’s labour platforms

It has become common practice among freelance platforms in the West to charge fees to workers, by taking a percentage of the negotiated price for the service, but also by offering membership options to workers on the platform that give their profile greater visibility and allow them to connect more easily with potential clients.20 This practice is also common among Chinese platforms, though the membership and fee systems vary widely according to the competition model used. One important finding about Chinese platforms, not previously noticed in the west, is also the practice of requiring the workers to pay a security deposit to guarantee their successful completion of the work. In the western freelancing platforms, these guarantees (or escrows) are only required of clients, to ensure that they pay the workers for the work completed.21

On 680.com, when workers are directly hired, the platform takes 5 per cent as commission; these costs, covered by the worker, are among the lowest platform fees (680.com, NDa). For the application and submission competition model, even overall winner must remit a higher portion of earnings, some 20 per cent, to the platform. This leaves the worker with 80 per cent of the announced amount after having successfully completed the job (680.com, NDb). Similarly, for piece-rate works, there is a 20 per cent service charge (680.com, NDc).For software development projects, workers are required to make a guarantee deposit of 30-50 per cent of the project reward, depending on the size of the project, to the platform. This amount cannot be withdrawn before the project has ended successfully (680.com, NDd).

EPWK.com, meanwhile could be considered as one of the lowest service charges platforms, as it has eliminated most of the service charges since 2014 after it received its first venture capital investments worth 20 million Yuan.22 The platform is currently free for basic functions but charges for additional services such as VIP memberships for workers, which consist of a range of extended services, such as better visibility, security services, and other business management assistance.23 Under the current model, EPWK.com workers could receive 100 per cent of the value for direct bidding and direct employment tasks. For the competition reward model, however, the platform still retains a 20 per cent of charges, in which 10 per cent is used for promotional purposes and the other 10 per cent is equally shared between those who participated but who were not ultimately awarded. These fees are deducted from the award when the job is posted on the platform; for example, when a customer post a job successfully on the platform with 100 Yuan award, the platform will charge 20 Yuan immediate and left with 80 Yuan available for the job seekers to bid for.24 For piece-rate works, meanwhile, workers receive 90 per cent of the posted value of the job, with 10 per cent taken by the platform for promotion and administrative services.25

ZBJ.com has changed its membership system and service charges over time. Most of the changes seem have resulted in an increase in charges levied to workers or have attempted to differentiate between the services offered to members based on their membership level. Initially, ZBJ.com used a “pure commission model”, levying a 20 per cent service charge on each project between 2005 to 2012. From 2013 to 2015 June, they changed the fee structure to a “commission + membership model” that allowed for the reduction of service charges (still levied as a percentage of the total value of the task), depending on the membership level. Then, after receiving a vast sum of venture capital (2.6 Billion Yuan), ZBJ.com sought to enlarge its market share and attract new users by removing all service charges for project deals (except those “competing designs” and piece-rate projects still keeping 20 per cent service charges) (see Qilu Evening newspaper, 2017). This strategy was meant to attract platform workers who had previously been on fee-charging platforms.

In the competition for market share, platforms sometimes subsidize participation from workers and clients using venture capital funding. After capturing a substantial part of the market, these platforms have sometimes later changed their policies to improve profitability. Indeed, as of 30 June 2017, ZBJ.com had become to be the largest platform in China, and by 2019 the platform claimed to have 14 million workers. After achieving market dominance, ZBJ.com again changed the membership system and reintroduced “Technical service charges” to workers, which varied from 2 per cent for high-level members (高级会员), 6 per cent for mid-level members(中级会员) to 10 per cent for low-level members (普通会员) depending on level of membership.26

Table 5. The ZBJ membership system and its associated fees (as of August 2019)

|

Membership Type |

Membership version |

Membership (card) fee |

Technical service charge |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Registered (注册版) |

Basic (普通会员) |

0 Yuan |

20% |

|

Standard (标准版) |

Fixed workshop (固定工位版) |

666 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

20% |

|

Office version (专属办公室版) |

666 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

20% |

|

|

Tailor made office version (定制办公室版) |

1188 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

20% |

|

|

Enterprise (商家版) |

Roaming workshop (漫游工位版) |

888 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

10% |

|

Fixed workshop (固定工位版) |

1188 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

10% |

|

|

Dedicated office (专属办公室版) |

1188 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

10% |

|

|

Tailor made office (定制办公室版) |

1588 Yuan/month/space (or above) |

10% |

Note:

Their stratified membership structure depends on how much workers are willing to pay. Initially, high-level membership is 5980 RMB/month, mid-level membership is 2980/month, and low-level membership is free of charge. What membership offers, meanwhile, has continually changed over time. The membership version and the membership fees were later changed and further diversified according to the prices outlined above (as of August 2019). In addition to membership fees, which now range from 666 to 1588 Yuan/space and are administered on a monthly basis, the platform also has technical service charges that are administered per task completed. For basic membership this fee is 20 per cent, for enterprises, who tend to pay a slightly larger membership fee, the technical service change is less at 10 per cent. (See Table 5).

In this current version of the membership system, ZBJ.com has given special rights and incentives to workshop members as a way of promoting targeted growth on the platform and recruiting more workshop users (opposed to individual members who do not have any workshop space). These incentives include a “temporary measure” to reduce the transaction fee to 6 per cent for workshop (enterprise) members from 01 July 2019 to 30 June 2020.27 Additionally, membership has an impact on job distribution, sometimes at the expense of matching workers and clients according to workers’ skills and clients’ needs, and new incentives give preference to workshop members in the distribution of tasks. ZBJ.com has also started collecting high “integrity guarantee deposit” (诚信保证金) according to membership level and experiences (hereafter guarantee deposit), ranging from less than a hundred to several hundred RMB, depending on the project size, for potential violations of regulations and related fines.

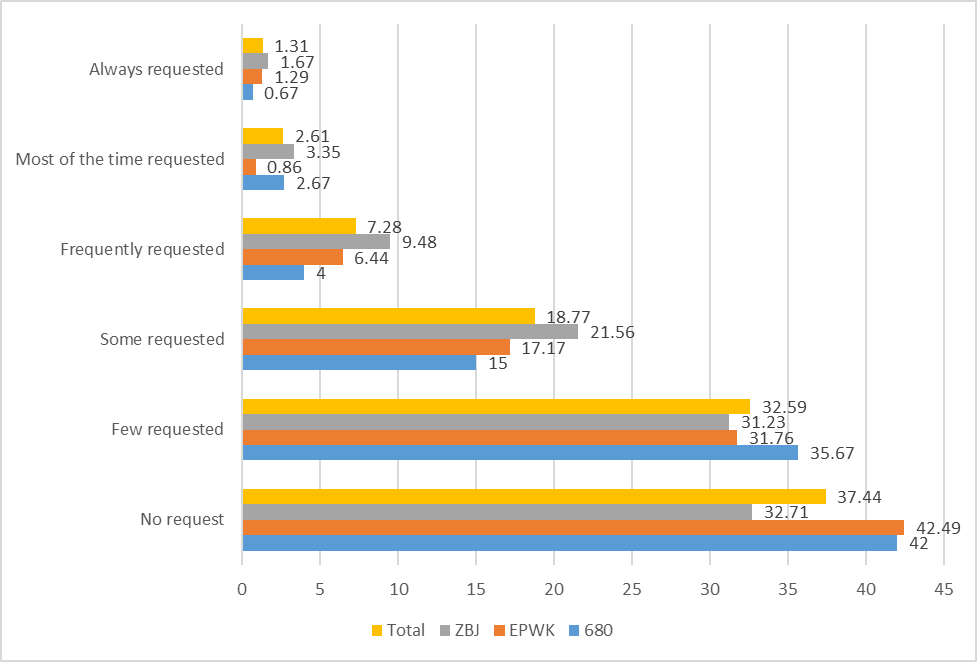

Table 6, below, shows the survey results of the types of fees that platforms workers pay. Across all platforms, 72.1 per cent of respondents report not having to pay fees. As discussed before, those who never pay fees are either exempt because of platform policies or because of the types of competition models they work on, such as piece rates on EPWK.com where no charges are administered directly to the worker. For workers who work regularly or who do large volumes of platform work, they typically register for a formal membership in order to minimize overall transaction costs and increase their opportunity to receive jobs. In total, 13.4 per cent of the overall respondents indicated that they paid a registration or membership fee.28 Fees were also more common among those who engage in bidding and application-submission related jobs. These workers often need to pay “deposits” after successfully bidding on the job, regardless of whether they have a membership or not. Seventeen per cent of workers responded that they had paid this type of fee, a substantial rate, but one that is not surprising given that application-submission and bidding together accounts for 40 per cent of all jobs according to our competition model classification.

Among the three platforms, ZBJ.com has the lowest percentage (64.7 per cent) of respondents responding that they “don’t pay” fees but the highest percentages in all other fee-paying categories. As workers could select more than one answer in this question, this suggests that either workers do not pay for some tasks, but may be paying multiple types of fees for other tasks or services offered. Moreover, 17 per cent report having to have paid guarantee deposits. Interestingly, responses from 680.com show that at present, this platform could be the lowest in terms of fees charged to workers.

Table 6. Workers’ experience in paying fees to platform and type of fee paid29

|

Fees |

Platforms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Total |

|

|

Didn’t pay |

81.0 |

77.7 |

64.7 |

72.1 |

|

Registration/membership |

9.0 |

13.3 |

15.8 |

13.4 |

|

Deposits |

10.0 |

12.5 |

22.9 |

17.0 |

|

Training |

7.7 |

10.7 |

10.6 |

9.8 |

|

Others |

4.7 |

6.0 |

7.3 |

6.3 |

|

Total observations |

300 |

233 |

538 |

1,071 |

In addition to asking workers about their experience with fees, we also sought to understand their perceptions by asking about whether workers felt the platform was fair. Workers’ perceptions of “fairness” could be influenced by different dimensions of this type of work. Given the direct relationship between competition models and fee charging structures, however, our analysis focuses on whether workers think fee charging structures are fair according to the model of competition they typically participate it. These results can be seen below in Figure 9.

The figure below shows the cross-tabulation between the question of the most typical mode of competition used in by platform workers and the question of whether the workers feel the platform fees are fair. The general observation from the figure below is that respondents think the competition systems are mostly (over 90 per cent) fair. These rates are slightly lower for competition models including application submission (86.8 per cent), direct bidding (84.1 per cent), and others (87.5 per cent). ZBJ.com workers who do application submission work are the least likely to feel the fee structure and direct bidding systems are fair with only 83.6 per cent responding favourably.

Figure 9. Percentage of respondents indicating that the competition method is “fair” by category

We further asked respondents their views about issues on the platforms’ operation systems, such as the fairness on the rating system, freedom to rate customer, and whether platforms frequently change the pricing policy on the platform. Whereas affirmative responses to these first two questions can be interpreted positively with respect to platform fairness, high values in this third question are more likely to indicate unfavourable conditions. Approximately three out of every four workers felt they could freely rate the customers they work with. A larger proportion of workers, over 87 per cent across all platforms, feel that the rating system is fair, but there are significant variations between the platforms with 680.com workers responding positively at a rate of over 10 percentage points higher than ZBJ.com Despite feeling that fee structures were fair, 37 per cent of workers stated that the platform changes its pricing policy frequently. Notably, these rates were highest among ZBJ.com, the platform that workers were least likely to describe as fair.

3.7 Pay, working time and job satisfaction among survey respondents

Having discussed worker demographics and the questions outlining platform task type, competition type, and fee structure, we now turn to a review of the working conditions on Chinese labour platforms. Our survey included questions on topics including: working time (paid and unpaid) and associated hourly wages, reasons for not doing more work, unfair treatment by requesters, and workers’ levels of satisfaction.

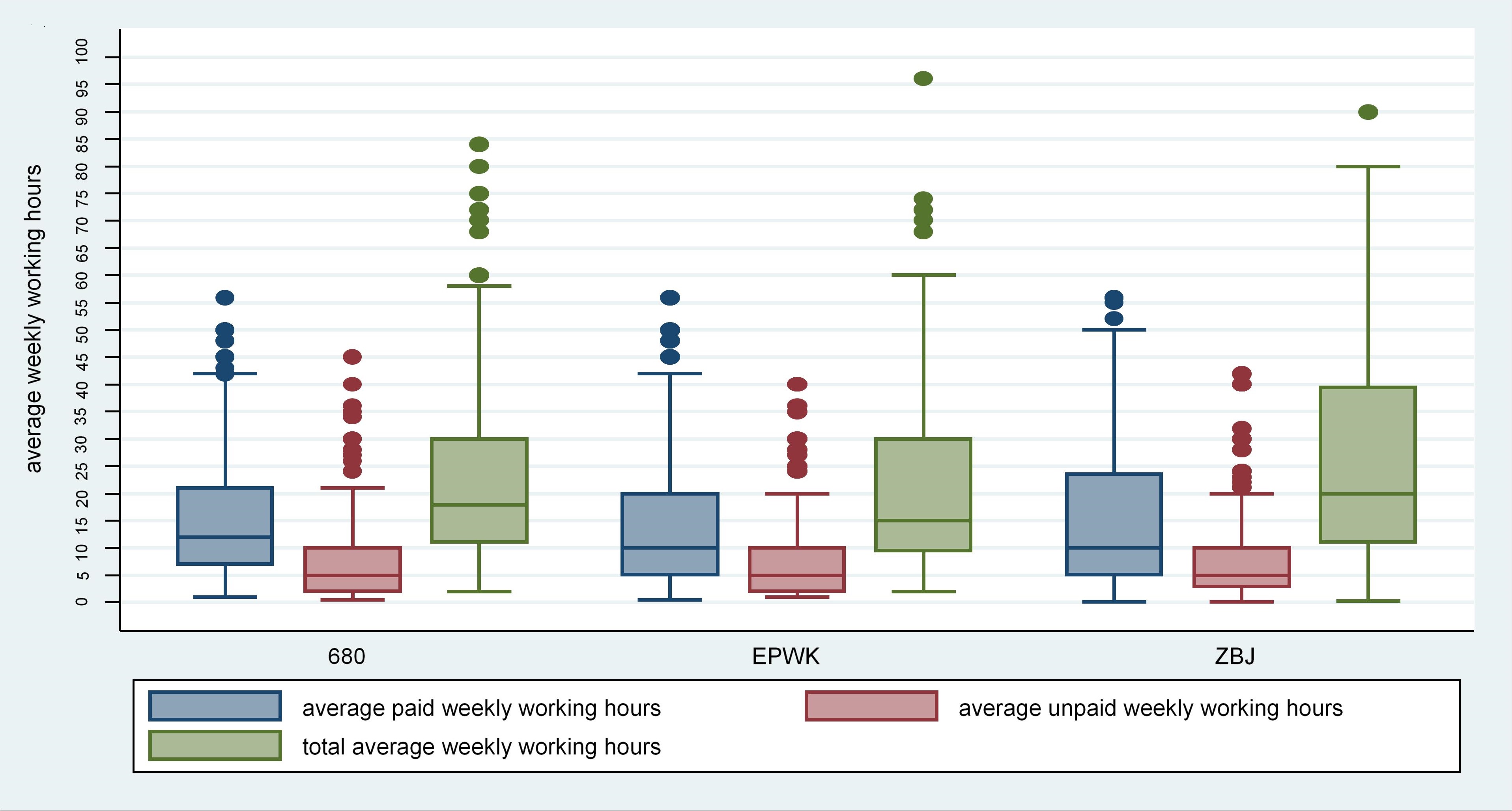

We first look at working time (paid and unpaid), and the associated hourly pay of the platform work. We asked a series of related questions about the working hours and wages to document the amount of time workers spend doing paid work and unpaid work, such as looking for jobs. We also asked about their average earnings so that we could impute hourly rates for both paid time and total time on the platforms. In our calculations, we elected to eliminate outliners that are larger than 97.5 per cent from the higher bounds. Questions were asked with regard to a worker’s experience in a typical week.

Figure 10 shows the distribution of paid and unpaid working hours. Overall, our survey revealed that in an average week, workers perform 15.6 hours of paid work and 8.3 hours of unpaid work, thus amounting to a total average weekly working time of 23.9 hours. This means that approximately one-third of working time is unpaid, a figure that is comparable to the findings of the ILO survey of microtask workers, but slightly higher than the findings of the Ukranian platform study, where 27 per cent of time was spent on unpaid activities (Berg et al., 2018; Aleksynska et al., 2018).

Figure 10. Average weekly working hours distribution of the platforms

As expected, workers who rely on the platform work as significant source of income spend more time on the platform. For these individuals the paid, unpaid, and total working hours are 24.6, 11.0, and 35.4 respectively. For workers who obtain a non-major source of income from platforms, their working hours are almost half that of their counterparts who are reliant on platform work for the majority of their income, and measure 13.2 paid hours, 7.5 unpaid hours, and 20.7 total hours. Both of these groups spend a substantive percentage of their time doing unpaid work, though this rate is lower for workers who are reliant on platform income, likely because they have become more efficient at finding work, thus saving themselves time. In total, reliant workers spend 30% of their time on platforms doing unpaid work compared to 36% of those who are not reliant.

As would be expected, the average weekly income also differs according to these groups. Overall it amounts to 372.72 Yuan per week (around 53.25 USD), but there are clear distinctions between the amounts from workers who regard platform work as their major source of income (599.42 Yuan or 85.63 USD) and spend more hours doing online tasks, versus those who state it is not a major source (309.91 Yuan or 44.27 USD) and spend less time on the platform.30 (See Table 7).

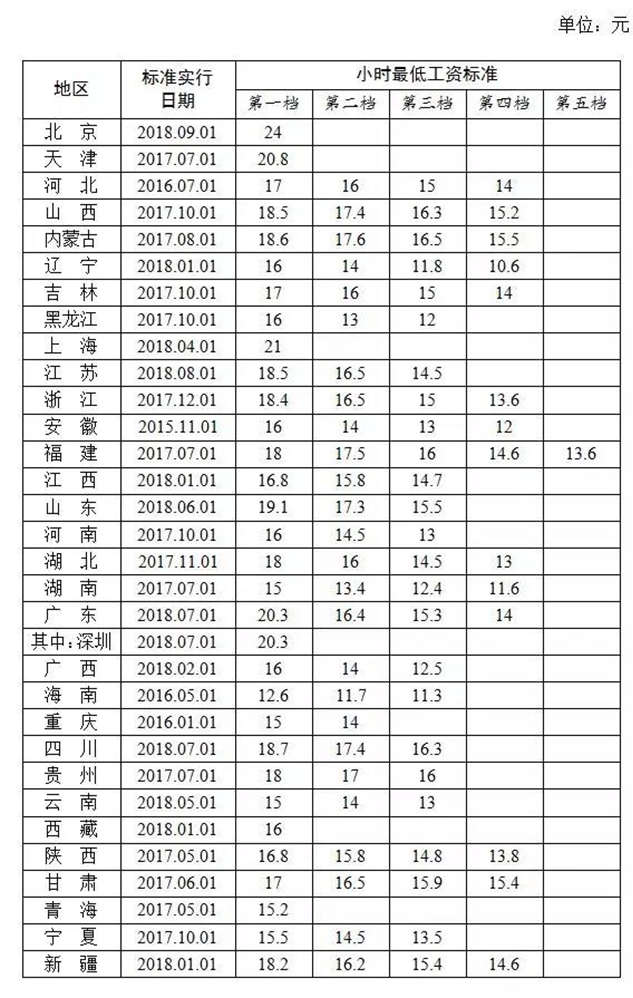

We have also calculated average hourly wages according to information respondents provided about their weekly working hours and wages. To measure this, we completed two different calculations: one for paid working time and one for total working time, inclusive of unpaid hours. If we limit the calculation to paid working hours, the average overall hourly wage is 32.59 Yuan, which is much higher than the 2018 national minimum wage. The median hourly wage is 17.98 Yuan (2.57 USD). According to the Labour Bureau, this is still higher than the lowest 2018 minimum hourly wage of 10.6 Yuan (for class four work) in Liaoning province, but lower than the highest rate of 24 Yuan per hour (for class one work) in Beijing (see further details at Li, 2018).31

If we include unpaid working hours in the calculation, wages drop. The average hourly wage is lower at 20.02 Yuan (2.86 USD), while the median hourly wage falls to 12.62 Yuan (1.80 USD). In accounting for workers’ unpaid time, we find that this results in a 42 per cent decrease in hourly wages. When comparing these figures with Indian workers on the AMT microtasking platform, we find that their average wages (3.40 USD in 2017) and median wages (2.14 USD in 2017) were higher than those in China (Berg et al., 2018).

Table 7. Average weekly earnings distributions, in yuan (RMB)32

|

|

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Major income |

Non-major income |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average weekly earning |

319.36 |

283.93 |

444.35 |

599.42 |

309.91 |

372.72 |

|

hourly wage (working hour only) |

30.32 |

27.18 |

36.46 |

29.57 |

33.38 |

32.59 |

|

Median hourly wage (working hour only) |

16.67 |

15.00 |

20.00 |

18.06 |

17.96 |

17.98 |

|

Average hourly wage (including unpaid working hour) |

19.01 |

17.15 |

21.92 |

16.93 |

20.87 |

20.02 |

|

Median hourly wage (including unpaid working hour) |

11.67 |

10.00 |

14.29 |

12.70 |

12.60 |

12.62 |

The survey included a question asking respondents about their overall satisfaction with online platform work. Single-measure job satisfaction questions such as this typically gauge workers’ feelings about the intrinsic characteristics of a job (the work that the person actually performs, autonomy, stress at work, among others) rather than extrinsic characteristics such as pay, contractual status, or prospects for promotion (Rose, 2003). The ILO survey of microtask workers revealed that only 6 per cent were dissatisfied and 1 per cent very dissatisfied (Berg et al., 2018). In Ukraine, four per cent of workers reported being dissatisfied and one per cent reported being very dissatisfied. Few workers in China expressed dissatisfaction with online platform work, reporting percentages that were even lower than the other ILO surveys. Only 2.4 per cent of workers stated that that they were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Nevertheless, to better understand why workers were dissatisfied, we asked a follow up open text question to enquire about the reasons.

Table 8. Satisfactory distribution of workers surveyed (percentage)

|

Platform |

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Very satisfied |

28.3 |

23.6 |

17.1 |

21.7 |

|

Satisfied |

49.3 |

51.1 |

43.7 |

46.9 |

|

Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied |

21.7 |

24.0 |

35.3 |

29.0 |

|

Dissatisfied |

0.3 |

1.3 |

3.4 |

2.1 |

|

Very dissatisfied |

0.3 |

0 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

|

Total observations |

300 |

233 |

538 |

1,071 |

Complaints related to low job availability and limited/unfair resource distribution. For example, one worker said, “the job availability is getting less and less; well-paying jobs are almost gone.” Another said, “the success rate is low, job quality is unstable, and the transaction fees are high.” Similar comments were expressed in the other surveys, where insufficient work and competition of work increase as more workers register on the platform. Indeed, twenty per cent of Chinese respondents indicated that there was not sufficient work on the platform. In addition, 18.2 per cent of workers whose primary source of income comes from the platform and 19.5 per cent of workers whose primary source of income comes from outside of platform also think that the “pay is not good.” (See Table 9).

Table 9. Percentage of workers responding affirmatively to the following reasons for why they are not doing more online platform work or other offline work

|

|

680 |

EPWK |

ZBJ |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Platform work |

Platform |

Not platform |

Platform |

Not platform |

Platform |

Not platform |

Platform |

Not platform |

|

Not qualified for the work |

25.0 |

21.8 |

35.3 |

24.6 |

22.6 |

21.6 |

26.0 |

22.3 |

|

Not enough work available |

15.1 |

22.2 |

20.0 |

27.1 |

26.9 |

22.0 |

22.1 |

23.2 |

|

Pay not good enough |

21.4 |

18.8 |

15.3 |

16.3 |

17.7 |

21.3 |

18.2 |

19.5 |

|

Don't have time |

27.4 |

33.9 |

17.9 |

29.1 |

23.5 |

30.0 |

23.4 |

30.8 |

|

Difficult to cash money made |

9.1 |

-- |

9.0 |

-- |

5.8 |

-- |

7.4 |

-- |

|

Other reasons |

2.0 |

3.4 |

2.6 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

5.1 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

|

Total observations |

252 |

239 |

190 |

203 |

447 |

450 |

889 |

892 |

By contrast, respondents who are very satisfied with their platform work are likely to comment that platform jobs are plentiful, they have working time freedom, and they can earn money during leisure time. For example, a worker responded that “it is stiff learning at the beginning; but gradually I am getting better and better”. Another said, “There are plenty of jobs, I can continue learning while earning money.” Even while working under similar conditions, the attitudes of workers vary, thus shedding light on the complexity of job satisfaction indicators.

When asked about their desire to do more platform work, 83 per cent of workers surveyed responded affirmatively. This was the same rate given was similar to the percentage of workers who stated that they wanted to do more non-platform work (83.29 per cent). On average, respondents would like to spend around 10 more hours per week doing platform work and 12.94 more hours per week doing non-platform work. These figures align with the survey results of AMT workers in America (10.5 and 11.9 hours) and India (11.2 and 11.4 hours), for the platform and non-platform works, respectively (Berg, 2016).

Why then, are workers not working more? For platform and non-platform work, the reasons tend to be the same and responses are consistent across the platforms. Except for the answer “difficult to cash money made”, which highlights situations in which platform workers may have money credited to their account but find it difficult to get this money off the platform and into a form they can use it, respondents were given the same choice of possible answers with respect to online and offline work. Their answers for not working more on platforms and in non-platform work respectively, included reasons such as not being qualified for the work (26 per cent and 22.3 per cent), that there was not enough work available (22.1 per cent and 23.2 per cent), and that the pay was not good (18.2 per cent and 19.5 per cent). There was greater variation between platform and non-platform work for those who responded that they did not have time. In this case, 30.8 per cent of non-platform workers cited a lack of time, a rate that was higher than for platform work (23.4 per cent). This difference could be attributed to the fact that a significant proportion of platform work is done by respondents on a part-time basis among other activities. Non-platform work, on the other hand, is more likely to require a fixed time-schedule, and perhaps more restrictive working hours leaving more respondents to feel that they didn’t have time to engage in this type of work.

When compared with answers from microtask survey, the overall percentage of Chinese respondents who were not doing more platform and non-platform work because they were unqualified was higher. This is a reasonable finding as the Chinese platforms surveyed are more diversified, as discussed above, with over half of the jobs in our dataset considered to be high-skilled. The microtask survey was directed at workers who were completing tasks that tended to have a much lower skill requirement (Berg et al., 2018). In contrast, one-third of respondents to the Ukranian survey, which covered a more diverse array of activities, reported that they needed further technical training (Aleksynska et al., 2018).

Nearly one-fifth of Chinese survey respondents stated that they were not doing additional work because the pay was not good (18.2 per cent and 19.5 per cent). This reveals that although the Chinese workers did not associate “low pay” with their overall satisfaction levels, they were willing to express a preference for higher pay when asked why they did not do more work than they are currently doing.

3.8 Relations with clients on the platform

Given the importance of the worker-client relationship to working conditions, including income and working time, our survey sought information on the client and worker interactions. In this section, we examine the treatment of workers by clients, discuss working time and monitoring arrangements, and then look at the issues of refusal to pay or rejection of work.