Public Employment Programmes in the Care Economy

The Case of South Africa

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic crisis have increased unemployment levels in the care economyith detrimental effects for care workers, the majority of whom are women . Additionally, the current context is highlighting inherent weaknesses in healthcare systems, exacerbating gender imbalances in the provision of paid and unpaid care work, and offering a micro experience of the consequences of failure to respond to the increasing demand for care globally.

Given their focus on labour intensity and greater levels of employment per unit of government expenditure, PEPs are a crucial instrument to respond to these challenges. This paper draws on learnings from South Africa to outline how PEPs can contribute to the reduction of employment, service provision and transitions to decent work in the care economy. Moreover, it provides insights into of how PEPs can form part of a support package to respond to the economic and social effects of COVID-19.

The South African experience shows that PEPs have contributed to the progressive realisation of decent work where as a first step in the trajectory, they have recognised and renumerated care related labour as work. However, where unemployment is persistent, the market fails to produce sustainable work opportunities at the levels required, and fiscal constraints reduce the state’s is ability to absorb PEPs workers, the programmes tend to lead to slow or non-existent progression beyond this first step. Furthermore, while the paper shows that the South African government’s Presidential Employment Stimulus provided much needed relief to the effects of COVID-19, it also highlighted the limitations of PEPs as a response to sector specific challenges within the care economy.

The case study raises a series of questions for further consideration about the role of PEPs in such contexts, particularly their efficacy in the provision of direct care services. Several options are available to government, including a recognition of such services as long-term and ongoing. Regardless of the policy choices made to respond to the different challenges, the state needs to embark on a fundamental redesign in the funding framework for all PEPs in the care economy to improve wage levels and structurally change how workers are transitioned into more decent forms of work.

Introduction

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines the care economy as the sum of all forms of care work including both paid and unpaid forms. Care work is further defined as the set of activities and relations that are required to meet the physical, psychological, and emotional needs of others. These activities can be categorised into direct care that requires physical proximity such as nursing a baby or teaching children, and indirect care which are all the activities that can happen without the person needing care but create an enabling environment for personal caregiving to take place e.g. cleaning and gardening

COVID 19 has put a spotlight on several aspects of the care economy. It has highlighted the weaknesses in many healthcare systems around the world as resources continue to struggle to keep up with the rising demands for healthcare

Public Employment Programmes (PEPs) provide an established mechanism that allow countries to respond to these needs while also addressing unemployment and other labour market challenges. PEPs include both Employment Guarantee Schemes and institutionalised programmes which share the common objective of direct employment creation using activities with high labour intensity in context where market employment opportunities are in limited supply. These programmes are primarily funded and implemented by government however, donor agencies can also play this role in collaboration with government

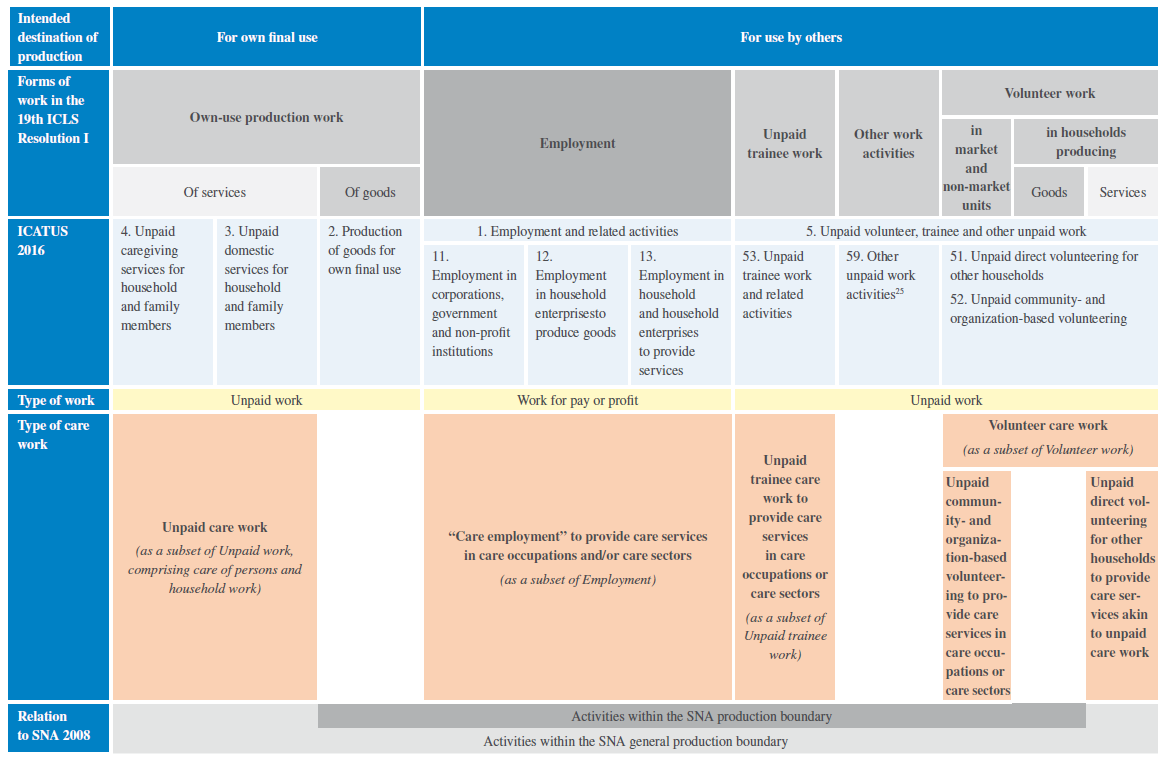

The care economy is inherently labour intensive and therefore has potential for effective implementation of PEPs as it ensures greater employment per unit of government expenditure. However, not all forms of care work are well suited to the design of PEPs. The diagram below depicts care work within the new definition of work introduced with Resolution I adopted by the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) which shifts the focus to the process of providing care and does not distinguish where and to whom the care is provided

Based on this framework, PEPs fall into the employment and related care activities, specifically the category called employment in corporations, government, and non-profit organisations. They are a form of employment where the care services provided are intended for use by others and the workers recruited in the care economy work for pay and profit. PEPs can often play the role of transitioning workers receiving no remuneration for the care they provide to others into paid forms of work.

Figure

Source:

It is useful to draw learnings from countries with experience in implementing PEPs within the care economy and to understand how they have contributed to the reduction of unemployment, service provision and transition to decent work. Given the current context, it becomes important to also understand how PEPs can form part of a support package in response to the economic and social effects of COVID-19. South Africa provides one such example and makes for a useful country case study for three reasons. First because of its pioneering role in introducing new approaches to PEPs, specifically in the care economy, that looked beyond traditional public works models to generate social value and extend social services to communities

This case study aims to present South Africa’s historical experience with implementing public employment programmes to deliver care services; discuss the emerging effects of COVID-19 on the delivery of care services, outline the stimulus interventions that are currently being implemented to support the care economy, and discuss the themes and opportunities that emerge about the role of PEPs in the care economy.

Overview of the care economy

South Africa’s labour market has a long history of systemic exclusion, disadvantage, and discrimination along racial and gender lines. Ten years into democratic governance those unemployed continued to be predominantly comprised of African and Coloured people, with young people making over half of this group. Moreover, women and people living in rural areas were particularly disadvantaged

This context explains the dynamics within the sectors that make up South Africa’s care economy namely the health care, social work, education, and domestic work sectors. The care economy in South Africa has three main characteristics: (1) care services are provided by public and private providers in both the formal and informal market with a substantial proportion of care work delivered through non-profit organisations (NPOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), (2) women perform the majority of the paid and unpaid care work, and (3) where it is paid, women are often underpaid, and their services are undervalued.

The first characteristic is a distinct feature of the primary healthcare and early learning delivery in the health and education sectors. In its report on the National Minimum Wage, the Commission noted that these two services are public goods which in many other countries are provided by the state, however, in South Africa this is largely not the case

The second and third characteristics of the care economy in South Africa are not unique to the country. Instead, it is a global problem that is underscored in Sustainable Development Goal number five which seeks to "achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls". Recognising unpaid care work and closing the gender wage gap are some of the priorities within this goal

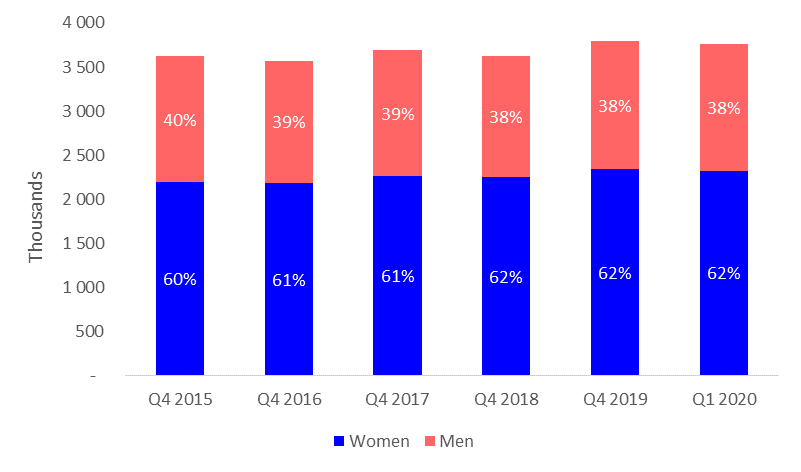

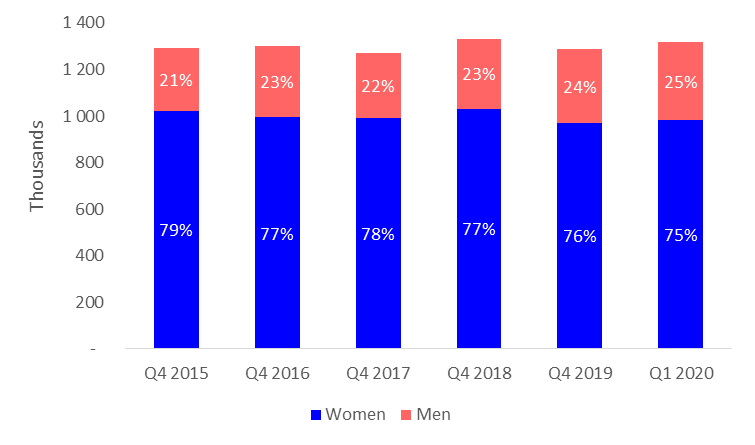

Figure

Source: Quarterly Labour Force Surveys, Statistics South Africa

The total number of employees in the community, social and personal services has increased but it has largely remained within a range of 3.5 to 3.7 million over the past five years. Overall, employment levels have grown by an average of less than 1% every year since 2015. Women constitute the majority of employees in the sector and continue to grow, although at a slow rate. Similar to other parts of the world, South Africa has a persistent gender wage gap across all sectors. Although this has decreased from 40% in 1993 to 16% in 2016, it has remained stagnant at this rate since 2007

This domestic work sector does not comprise any public employment programmes but is included here to provide an overview of the care economy in its entirety. A domestic worker is legally defined as someone who “performs domestic work in a private household and who receive, or is entitled to receive, pay” and includes cleaners, cooks, gardeners, people providing childcare and security.

Figure

Source: Quarterly labour force surveys, Statistics South Africa

Sectors delivering care services in the economy

A brief overview of each sector is provided below with a focus on sectors that have PEP components namely healthcare and education. The domestic work, social work and higher education sectors are excluded because these do not include any PEPs.

Healthcare

The provincial health departments have the mandate to provide primary, secondary, and tertiary health care services through public facilities in the districts while the national department is responsible for policy development and oversight1. Public facilities are required to provide care to all South Africans with reimbursement for these costs funded from tax income through provincial departments allocations according to the Division of Revenue Act2. Hence, these departments are the direct employers of workers in the sector

The South African National Health Act 61 of 2003 defines three broad categories of workers in the sector. Health care personnel are all workers in the health service; health care providers are people within the sector that directly provide health care services such as medical practitioners, pharmacists, dentist, medical specialist, nurses, and auxiliary nurses; health care workers are all other workers who are involved in the provision of health care services but are not providers such as cleaning staff, community health workers, and counsellors

Another significant challenge in the sector is the difference in the quality of care services in well-resourced private facilities compared to underfunded publicly owned and managed facilities. For the majority of citizens in South Africa (71.5%), the first port of access to healthcare services is from public sector providers which has created pressure on the system and has constrained the delivery of quality services. Although some progress has been made since 1994, challenges such as critical shortages of professional staff, inadequate resources, and weak implementation remain

Education

The Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) are responsible for the education sector in the country. DBE governs the delivery of early childhood development, primary and secondary school education in public and private schools across the country whereas DHET is responsible for tertiary and vocational education. The education sector overall is a high priority sector in South Africa as reflected in the total budget that is allocated to the sector. The country spends approximately 20% of the total budget on education which is a relatively high proportion by international standards

Early childhood development

Although discussed under education, it is worth noting that in South Africa, early childhood development (ECD) currently falls into the mandates of three departments: health, social development, and education. However, to date DBE and DSD have played a direct role in the oversight of ECD programmes whereas health’s contribution has been more indirect through its provision of primary health care for children. A transition is underway to consolidate the oversight responsibilities within the DBE and shift it from social development

An ECD programme is defined as a programme that provides early learning and development opportunities, daily care, and support to children from birth up to and including six years, in accordance with the provisions set out in the Children’s Act. It includes centre and non-centre based programmes such as a playgroup, a toy library, mobile early childhood development programme and a parental support programme

A critical challenge that precipitated a commitment to universal access was the current low levels of children attending facilities that provide early learning and care. More than half the children aged three did not attend an ECD facility, many children continue to experience malnutrition and infant mortality rates are still high

A constraint identified in these programmes is that they are predominantly delivered by community based ECD programmes, NPOs and NGOs. Many of these rely on fees from parents or guardians and donor funding. Some of the programmes are registered or conditionally registered with the DSD while many remain unregistered in terms of the Children’s Act 38 of 20054. Fully registered and conditionally registered programmes are eligible to receive subsidies from DSD which complements other sources of income however, not all registered programmes are funded as priority is given to programmes that serve poor children

Despite the Act prohibiting unregistered programmes from providing ECD services to children, 1.5 million of children in poor communities in the country participate in these programmes and they form part of the service delivery ecosystem

Basic education

More than half of the budget allocated to the education sector is allocated to basic education and is transferred to provincial departments to implement through the district-level offices that are responsible for school management

The schools are further divided into income quintiles to target appropriate support to disadvantaged communities. Quintile 1 to 3 schools do not collect any school fees while quintile 4 and 5 supplement subsidies received from government with school fees. The allocation of government funding per learner in the first three quintiles was R1243 compared to only R215 for learners in quintile 5 schools

There are approximately 410 000 teachers in the basic education sector, and they make up the majority of the staff complement in the sector

This section has provided a brief overview of some of the key sectors in the care economy with a focus on providing context for those that implement PEPs programmes. For health and basic education, the challenge is less about access to the service but improving the quality care provided whereas for ECD where many children, especially those in poor areas, do not attend any ECD programme, access to the service is also a critical challenge. The next section describes existing PEPs in the South African care economy with specific attention given to the services provided, the evolution of the programmes, criticism and challenges that have been experienced to date and the contribution that the programmes have made to the care economy.

The role of the Expanded Public Works Programme in the provision of care

The Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) is one of the instrumental mechanisms through which the government is addressing unemployment. Launched in 2004, this PEP is currently implemented in four sectors, namely, the infrastructure, social, environment and culture, and the non-state sectors. All spheres of government and state-owned enterprises are required to create work opportunities by increasing the labour intensity of infrastructure projects and delivering publicly funded programmes in ways that optimise employment creation. Moreover, the programme targets vulnerable groups and seeks to achieve pre-determined targets of work opportunities for women, youth and people living with disability

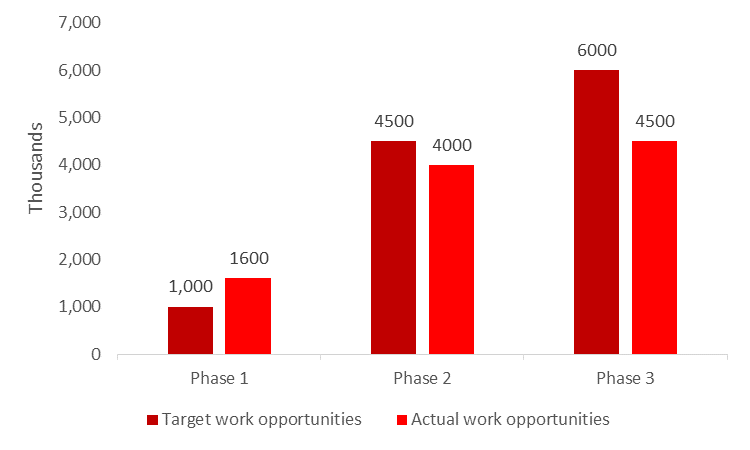

The programme is implemented in phases of five years and is currently in its fourth phase which began in April 2019 and will conclude in March 2024. The aim of the first phase (2004 - 2009) was to alleviate unemployment for a minimum of 1 million people in the form of work opportunities and the second phase (2009 - 2014) sought to create 2 million FTEs (equivalent to 4,9 million work opportunities) for the poor and unemployed through the delivery of public goods and community services. The third phase (2014-2019) aimed to create 6 million work opportunities while the ongoing fourth phase is targeting 5 million work opportunities across all four sectors

Figure

Source:

The programme’s performance against its targets has been in decline since phase 2 with a significant underperformance reported in the third phase. A new reporting system for EPWP introduced in this phase created several changes to reporting such as a new requirement to upload certified copies of ID documents which significantly added to the reporting burden. The system also enabled verifications of reported participants against other databases such as the government employees and Department of Home Affairs’ death register to ensure participants were not permanent government employees or ghost workers. These additional verifications and the challenges with collecting the information required emerged as key reasons for not achieving targets along with reductions to baseline budgets that occurred during implementation

The most prominent PEPs in the care economy can be found in the EPWP’s Social Sector and the components of the Community Works Programme. The Social Sector seeks “to draw significant numbers of the unemployed into productive work through the delivery of social services to enable them to earn an income and to provide as many EPWP participants as possible with education and skills to enable them to set up their own businesses/service or to become employed”

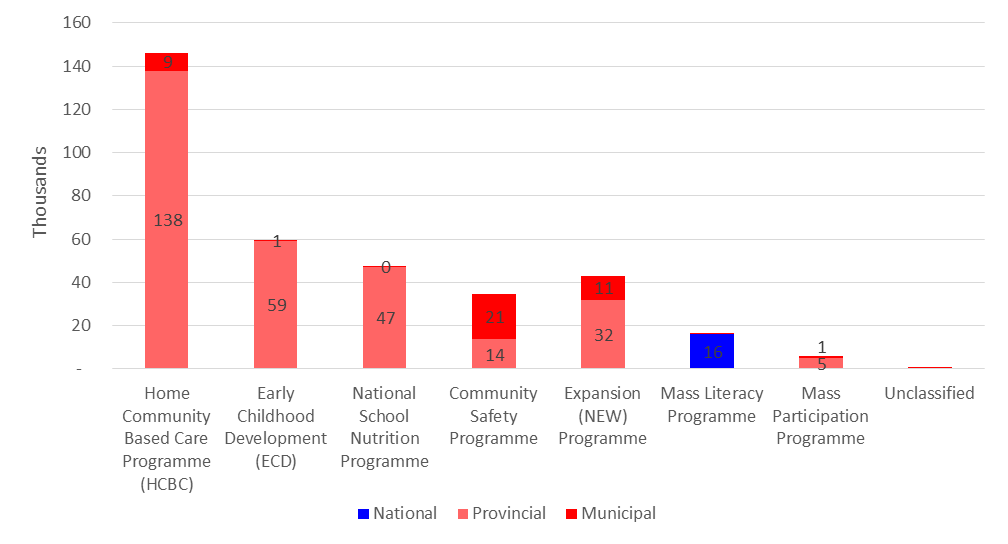

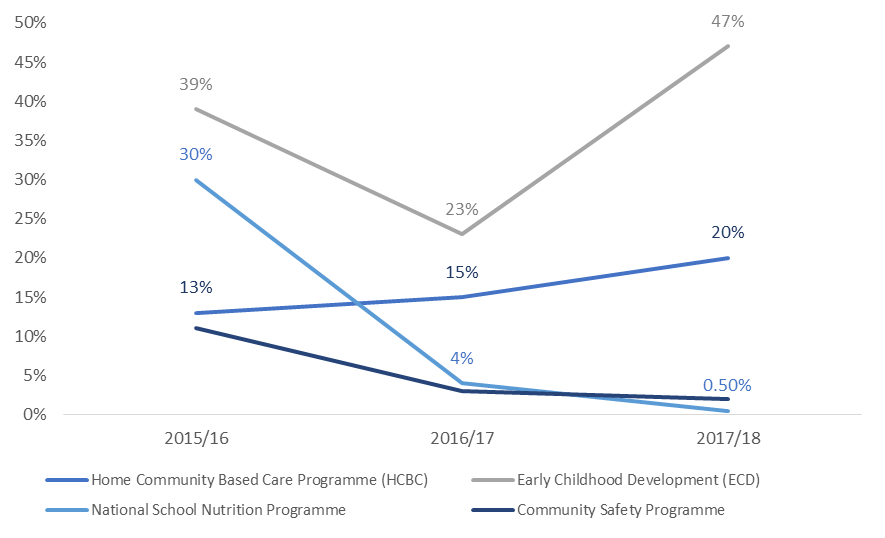

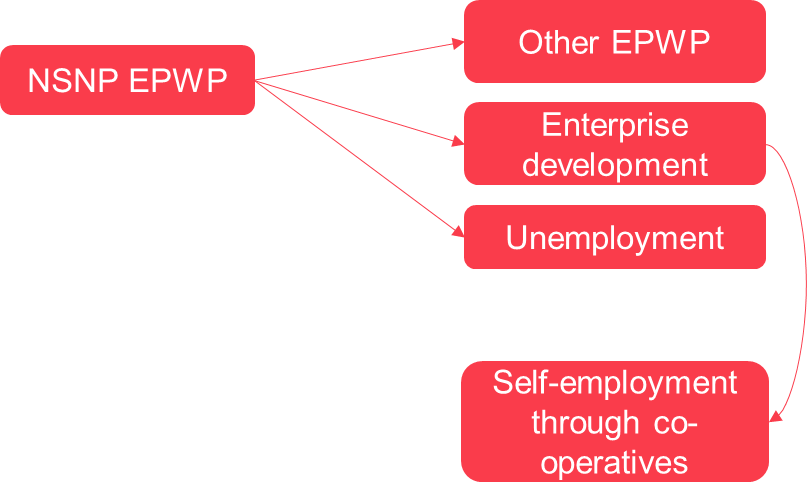

The Social Sector’s two flagship programmes are the Home Community Based Care (HCBC) and the Early Childhood Development (ECD). In addition to these two, the sector also delivers the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) in the education sector as well as other services that are not directly related to care such as community safety and sports sector’s mass participation programme.

Figure

Source:

Although the total number of programmes in the sector has grown since inception in 2003, the HCBC, ECD, NSNP continue to contribute the majority of employment creation in the Social Sector. Together, these programmes contributed 72% (254 000) of the total FTEs in the Social Sector in phase three of the EPWP

The labour standards and conditions of the programme are outlined in the Ministerial Determination for EPWP, the Code of Good Practice for Special Public Works Programmes, and the Learnership Determination for unemployed learners. The Ministerial Determination of 2012 establishes the standard terms and conditions of employment for the EPWP focusing on, amongst others, the terms of work, normal hours of work, meal breaks, special conditions for security guards, rest periods, sick leave, maternity leave, and payment

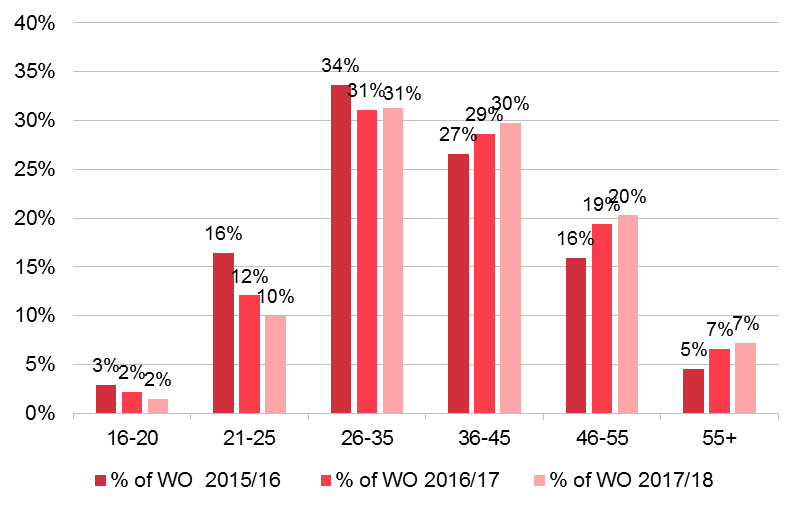

In addition to adherence to the ministerial determination and creation of work opportunities and FTEs, the sector is required to meet demographic targets (55% youth, 55% women and 2% persons living with disabilities) and prioritise disadvantaged groups when recruiting participants for the programme. Due to a dominance of women in the care economy, the Social Sector consistently achieves its target for women but misses the targets for participation of the youth and people living with disabilities. In Phase 3, the sector’s actuals were 80%, 45% and 1% respectively for youth, women and persons living with disabilities.

Figure

Source:

The employment status of the individuals in the programme remains a source of contention. While the Ministerial Determination refers to them as workers, the EPWP programme has over the time used terms that avoid reference to them as employees such as participants or beneficiaries. Similarly, the Ministerial Determination speaks of wages but, the programme has often referred to payments as stipends to avoid creating expectations of benefits and protection afforded individuals categorised as employees or workers. The latest programme strategy for Phase four mainly uses the term participants and refers to payments as wage which is the language this report uses unless directly quoting other sources where different definitions are used.

Outline of programmes

Home community-based care and community health workers

Home Community-Based Care (HCBC) is one of the Social Sector’s flagship programmes and is implemented by both the Department of Social Development (DSD) and the Department of Health (DOH). The workforce in the programme includes both the Community Health workers on DoH’s Community Health Worker programme and home-based care workers on the DSD programme. The responsibilities differ in that CHWs render a more comprehensive set of services while home based care workers deliver care in the home along with other services that they are trained in.

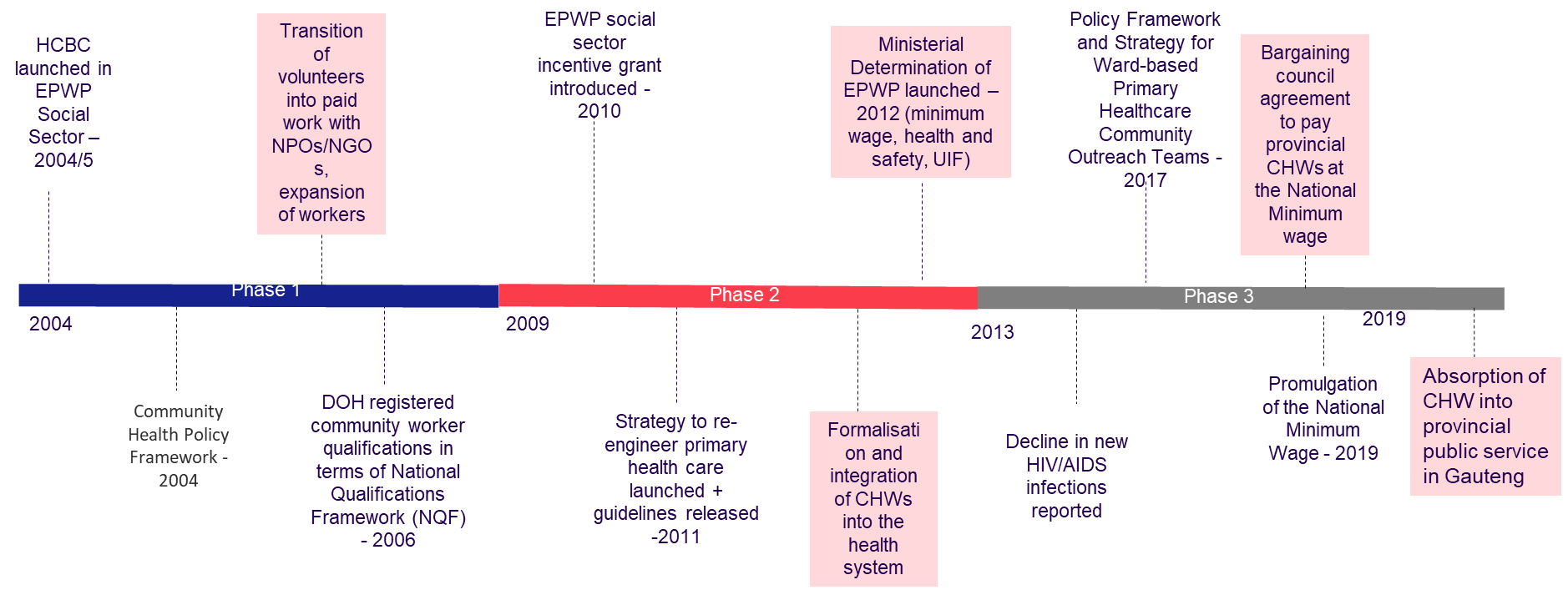

Figure

The HCBC programme was introduced to intensify the country’s response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and reduce its effect on vulnerable communities. The programme’s strategy entailed bringing services closer to households that had limited access to the formal health sector using formal and informal caregivers placed in the community

In Phase 1 of the programme, work opportunities were targeted to expand the pool of employed volunteers, rolling out a bridging programme to the CHW programme through learnerships and expansion of the programme through establishing new sites. Moreover, the programme sought to create opportunities to participants affected by HIV/AIDS and prioritised volunteers living with HIV/AIDS that were not receiving a state grant and adult dependants of terminally people

In the second phase (2009 - 2014), EPWP continued to be an important intervention for expanding service delivery and creating work opportunities. The design of the programme remained largely the same as in the first phase. An important change was the introduction of the strategy to re-engineer primary healthcare service delivery. Since 2011, provinces have been employing CHWs directly as part of the strategy to build outreach teams to offer primary health care services in the wards. This was a significant step towards formalising CHWs and was welcomed within the sector however, the lack of an accompanying policy and guidelines led to fragmented implementation approach across the provinces with each paying different wages and implementing different conditions. Another change was the classification of programmes into preventative, therapeutic, rehabilitative, long-term maintenance, and palliative care. Participants of the EPWP Social Sector continued to receive wages and skills training and a new focus was added in this phase to develop participant owned and run Small Micro and Medium Enterprises (SMMEs) to stimulate self-employment once they exited the programme

The HCBC and community health worker programme has remained an important pillar of the sector in the third phase. The fragmentation in delivery of the re-engineering strategy led to the development of a policy that could bring coherence and alignment to the implementation. This policy, titled the Policy Framework and Strategy for Ward-based Primary Healthcare Community Outreach Teams (WBPHCOT), was introduced in 2017. It is an important milestone in the programme that will streamline the re-engineering of primary health care and formalisation of ward based primary health care outreach workers within provincial departments of health

Most of the funding for the HCBC and CHW programme was and continues to be through equitable share allocations and conditional grants transferred to provinces. At the provincial level, EPWP within HCBC is largely funded through the Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Conditional Grant to provinces which is transferred to the provincial DoHs and transfers and subsidies to the provincial DSD. Additionally, provinces and municipalities receive an incentive grant which is designed to reward public bodies for performance in terms of FTEs created. This grant is typically used to either increase the number of workdays available to existing employees, provide wages to unpaid volunteers or increase the total number of participants

Early Childhood Development

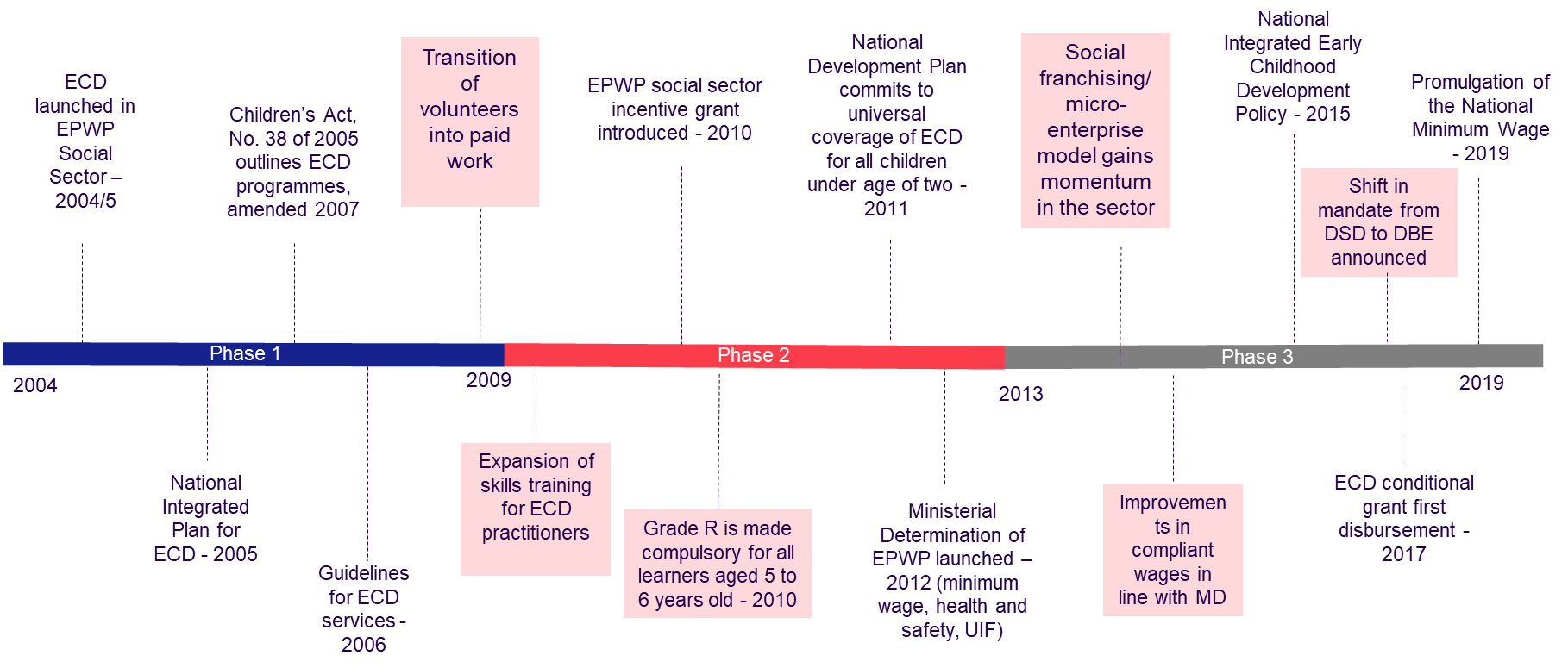

The Early Childhood Development (ECD) PEP is another important flagship programme for the social sector that was included in the first phase for the potential it showed to create jobs while also addressing a pressing service delivery challenge in the education and care of children. It is implemented by both the DSD and DBE with the former focused on earlier years from birth to pre-school and the latter on the early years as well but with a particular focus on Grade R5.

Figure

The EPWP ECD programme in the first phase comprised a mix of learnerships, work placements at ECD sites, support staff and programmes that enrolled parents to. Several legislation, plans and guidelines were promulgated over this time that created a supportive environment for the implementation of the programme. The guidelines for ECD services sought to standardise provision while the amendment of the Children’s Act in 2007 formally outlined what is considered an ECD programmes.

During the second phase, the National Development Plan (NDP) gave further impetus for the implementation of ECD nationally by including universal access as one of government’s 2030 targets

In phase 3, the sector implemented the policy and conducted integrated training across all implementing departments to ensure aligned understanding of roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, National Treasury responded to the requirements for funding and infrastructure availability in providing ECD through the introduction of a dedicated conditional grant for ECD administered by DSD. The ECD conditional grant was introduced in 2015/16 with the first disbursements taking place in the 2017/18 financial year

The government has announced a shift of the ECD mandate from the DSD to DBE and in so doing has reiterated the importance of ECD and ensured that it will be better aligned to basic education which will resolve some of the discrepancies in implementation that currently exist between the two departments. This move will also provide better synergy between the training opportunities within the programme and the services delivered within the programmes.

A constraint to scaling that is embedded in this funding model for ECD is that the conditional grant framework applies a per child per day model that prioritizes nutrition to allocate subsidies to qualifying programmes

National School Nutrition Programme

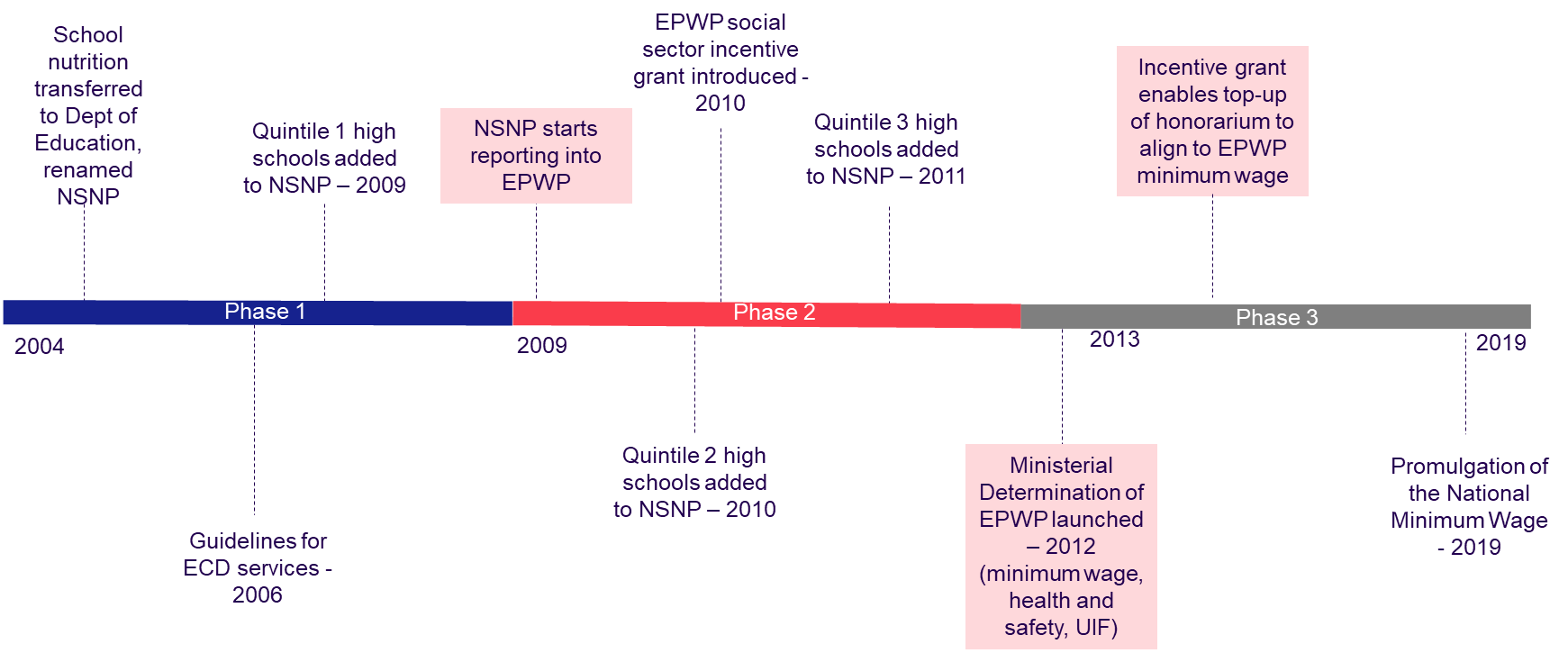

Figure

The National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) is managed by the Department of Basic Education and seeks to provide at least one nutritional meal to learners in poor primary and secondary schools (quintile 1 to 3 schools), educate learners and communities about nutrition and facilitate food production through gardens and food projects in schools

The NSNP started reporting into EPWP in the second phase which interfaces with two of the three objectives stated above through the recruitment of and payment of wages to food handlers and gardeners to work in the schools. Food handlers are responsible for cooking and preparing food for learners. Chief food handlers are also recruited to provide supervision, place, and receive orders, ensure registers are signed and service providers honour delivery commitments. The chief food handlers have reduced the administrative burden that used to fall on teachers to manage the NSNP in schools.

A major challenge experienced in the programme was the conditions of work for food handlers who were recognised in the conditional grant framework as volunteers but identified as EPWP Social Sector participants in others. The conditional grant framework specified that these workers were volunteers who should receive an honorarium while according to EPWP, they were entitled to the minimum wage. This discrepancy led to non-compliance with the Ministerial Determination (MD). An evaluation of phase 2 of the NSNP showed that EPWP participants were generally receiving 60% of the prescribed minimum daily amount

The NSNP in EPWP is funded by a combination of the NSNP conditional grant and the EPWP incentive grant to provinces with the latter predominantly used to top-up the payment to ensure they align with the ministerial determination. The grant framework specifies that a minimum of 96% of the grant should be spent on school feeding, 0.6% on kitchen facilities, equipment, and utensils, 3% on administration and 0.4% on nutrition education

Community Works Programme

The CWP is part of the non-state sector of EPWP and delivers the same care services already described above namely HCBC, ECD, school support as well as care for persons with disability. The main difference between CWP and the programmes in the Social Sector lies in the design of the CWP which deviates from traditional public employment programmes in several ways. Firstly, it is designed to provide participants of the programme with ongoing, part-time work (two days per week). Secondly, it is implemented at the local level and follows a participatory approach that allows communities to identify the needs. Thirdly, the programme aims to achieve a 65% labour intensity which ensures that a significant number of the unemployed can be benefit

The programme is implemented at sites with each one targeting 1000 unemployed people in local communities. Participants receive a daily rate for two days of work per week which adds up to 100 days per year of work with more skilled participants receiving a higher rate

A common criticism that has become associated with CWP is that while well conceptualised and designed, the implementation has been unable to realise the full potential of the programme

Barriers to delivering quality care services in EPWP

Over the different phases, the EPWP has faced considerable criticism for its implementation and governance flaws. These are argued to have compromised both the conditions of participants in the programme and the quality of services delivered through the different sectors. These include poor adherence to prevailing minimum standards and conditions such as the minimum wage, perverse effects on women and limited exit pathways for participants post completion of the programme. The challenges largely point to the inability of the PEPs in the Social Sector to continue to improve participants conditions beyond the basic minimum contributed to the early years following the introduction the programme. The challenges are described in greater detail below.

Poor adherence to principles, minimum standards, and conditions

The universal principles for EPWP were introduced in Phase 3 to improve uniformity in implementation across a number of areas such as how participants are selected, compliances to the EPWP minimum wage and conditions laid out in the Ministerial Determination, ensuring that output created generate a benefit for the communities and that projects are adhering to the minimum labour intensity set for each sector.

Table

|

|

|

|

Adherence to the EPWP minimum wage and employment conditions under the EPWP Ministerial Determination |

Many of the core features of the EPWP relates to the Ministerial Determination for the EPWP and the associated Code of Good Practice. The EPWP Ministerial Determination sets out minimum wages and working conditions that are critical social tools for protecting vulnerable EPWP participants and for the EPWP to become more effective as a social protection instrument. Monitoring compliance with this legislation and acting when there is a lack of compliance will receive greater priority in all the EPWP programmes. The EPWP programmes/projects must seek to achieve full compliance with this determination in Phase IV. |

|

Selection of EPWP participants based on (a) a clearly defined process and (b) a defined criterion |

Defined targeting considerations to ensure fair and transparent selection criteria, but at the same time keep targeting operationally as simple as possible. The selection of each EPWP participant should be done on a clear set of criteria to minimise patronage and abuse during selection. The selection should also happen in accordance with clear transparent and fair procedures.

|

|

Work provides or enhances public goods or community services |

For the EPWP to fulfil its transformative, developmental, and social protection potential, the focus of developing assets and services that in particular enhance the social and economic benefits to the poor, is important. The work output of each EPWP project should contribute to enhancing public goods or community services, with a bias towards the poor. The core of this requirement is that EPWP projects are not deployed on activities that will benefit private companies or contribute to private sector profit generation. This excludes the use of private sector companies as implementing agents. In addition to this, a focus on labour-intensive delivery methods while maintaining quality standards further enhances benefit. |

|

Minimum labour intensity (LI) appropriate to each sector |

A minimum LI benchmark appropriate to each sector has been set. Different types of programmes within each sector would also be encouraged to set their own benchmarks. |

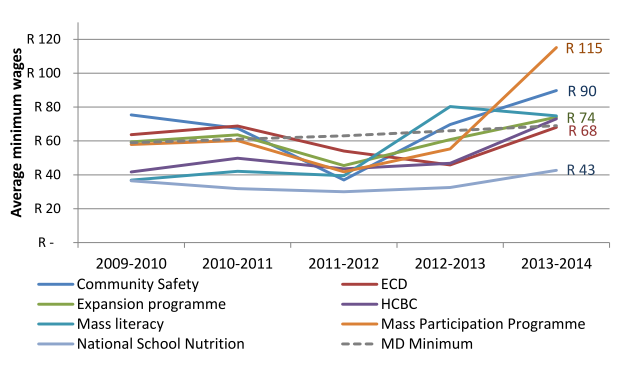

Compliance to the MD minimum wage

All of the PEPs in the care economy were paying wage rates that were below the stipulated minimum in the Ministerial Determination in Phase 2 of the programme

Figure

In 2013/14 the NSNP Food Handlers received a wage that was only 60% of the minimum stipulated in the Ministerial Determination (

It is well-documented that low wages and precarious employment conditions such as those experienced by CHWs and ECD practitioners leads to high turnover, meaning a loss of skills and a constant need to provide the required training to new staff

Figure

Source:

In comparison, ECD initially showed a decrease in non-compliant wages, but in the last financial year (2017/18), the proportion has risen to close to half of participants earning non-compliant wages. The discrepancy in wage payments of ECD practitioners was due to different decisions taken by NPOs regarding how much of the per child subsidy component of the ECD conditional grant to allocate to payment of practitioners

Late payments

Late payments, like non-compliant wages, are in contravention of the Ministerial Determination which requires at least monthly payment. There were cases of late payments identified across all Social Sector programmes with some as late as several months. Programme managers’ untimely sign-off on wage expenditure, poor planning, and late disbursements of the incentive grants are some reasons that explain the occurrence

Duration of work

The Ministerial Determination on EPWP is clear that the participants are employed on a temporary basis. This is an intentional part of the design to avoid permanent employment under PEPs conditions and limit displacement of private sector jobs

“[For HCBC and ECD, there is a] recognition that whilst the Expanded Public Works Programme has performed innovative work in these areas, the delivery of these services is continuous in nature. Government and social partners need to recognise this reality and in turn develop proposals that will both strengthen non-state provision, but also provide support and direct employment by the public service”

Moreover, in their deliberation on the wage level and exclusions from the national minimum wage, the National Minimum Wage Commission expressed strong criticism of government’s dependence on low wages and unpaid work to deliver services that are considered public goods which should be provided by the state. “A large number of workers, mainly female workers, are employed in welfare and care work, at low wage levels. At least some of this work is undertaken on behalf of Government, and the low wages are partly a result of low levels of government subsidy”

The DoH’s WBPHCOT policy acknowledges the structural issues associated with the remuneration and status of workers (see below quote) however, it does not provide any resolutions to address it thereby putting the successful implementation of the policy at risk

“Community-based health workers are neither workers nor volunteers… [they do not have] the status of an employee, with the rights and benefits that come with it under South African labour law. By entitling them to a wage, government and non-government organisations acknowledge their labour and provide a form of compensation for their work, so they are not volunteers. This grey space leads to demotivation, hardship, and attrition. It makes it very difficult to create a sustainable system of community-based healthcare.”

This recognition from the policy shows the continued tension with recognising participants as workers that are entitled to full protection in accordance with the Labour Relations Act. Although the bargaining council agreement has led to an increase in stipends up to the national minimum wage and more structured training is offered, these participants continue to work under minimum employment conditions on 12 months contracts. More than 15 years into the implementation of EPWP, the repeated renewal of contracts that lock participants into low wages and low levels of protection is no longer an acceptable alternative to recognising the permanency of the care work delivered by these participants. As such, the argument above has received increasing support in the public domain, including unions and is amplified by protesting EPWP participants that are seeking proper recognition for the value that they add to the service delivery in the country.

Negative effects on women’s labour market outcomes

The recognition of unpaid care work and improvements to the employment conditions and standards are important contributions to the reduction of gender inequality in the labour market as well as disparities between women

Considering the mechanisms above, EPWP has produced a mixed bag of results. There is a general acceptance that EPWP has been able to bring volunteers into paid work, increase the supply of trained ECD practitioners, and has expanded the public provision of care services through the investment of public funds in the social sector programmes

The criticism lies in how these have been implemented and the resulting effects this has had on women in the EPWP programmes. As discussed above, the wages received by ECD practitioners in DSD programmes vary widely between programmes with many failing to comply with the EPWP minimum wage. Participants on the DBE programme received the EPWP minimum wage during their 12 or 18 months of training in their learnerships, however, once complete these participants would experience a regression if they transitioned into programmes that were non-compliant

EPWP in the Social Sector continues to receive criticism for its failure to address the barriers that women face and leading systemic change in the delivery of its programmes. Vetten

Limited pathways into sustainable employment

“It cannot be right that some members of the Expanded Public Works Programme have been on contracts for six and seven years. This is just slavery. They were supposed to have been trained long ago so they could go find employment and get into the real economy”

It is, however, important to add nuance to this challenge as some pathways are being created in the programme. A review of the EPWP in Gauteng points to an effective exit strategy for EPWP volunteer Community Care Givers who were trained as Child and Youth Care Workers in the programme and went on to work as in After School Care Centres

The Social Sector has tried to respond to this challenge in its design. The theory of change developed in Phase 3 includes an objective to ensure that participants find opportunities outside of EPWP

Interventions to improve pathways into sustainable employment

This section discusses the pathways available to participants when they conclude each of the PEPs in the care economy. Training and enterprise development are two interventions within EPWP that seek to improve employability and create opportunities for participants to exit into once the programme concludes. Additionally, there is the option for participants to be absorbed into the public service or find permanent jobs in the private sector. As discussed in the challenges, often participants find themselves stuck within EPWP or exiting back into unemployment.

Training within the EPWP has evolved from a strict and compulsory component of the programme to a requirement for training that enables participants to perform their duties. Over and above this, public bodies are strongly encouraged to invest in training that improves employability where possible. The Training Strategy for the Social Sector provides for three models of training: (1) sector prior training which refers to training of participants prior to implementing an active project, (2) sector on-site training which is training received during project implementation and (3) training for exit or graduation which is inclusive of further learning opportunities to participants with potential to increase learning, graduation, or both from EPWP to other career options. The training principles that underpin this objective include the need for public bodies to allocate budget (set at minimum of 5% of total project budget in Phase 3) for training programmes from their equitable share to complement any external funding that is received.

Despite the strategy, it remains a significant challenge to deliver training in the programmes due to limited training funds, public bodies failing to allocate the minimum 5% for training in project budgets, limited number of accredited providers and delays in the procurement of accredited service providers

Unlike training, most of the sector’s main strategic documents were silent on enterprise development throughout Phase 3 with greater prioritisation placed on training and developing a strategy for promoting it within programmes. The position is clear for enterprise development that it is not a core priority and the Social Sector programmes are mostly responsible for identifying and linking participants to opportunities that already exist within the ecosystem as opposed to taking responsibility for their creation

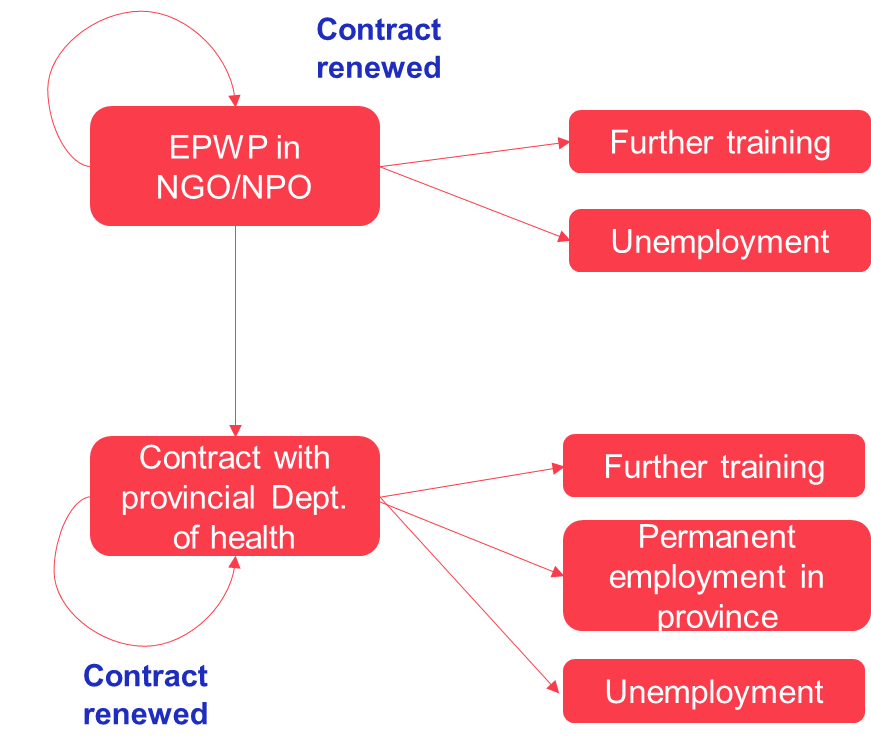

Home community-based care and community health workers

The pathways that are available to participants after they conclude the programme are outlined in

Figure

Training

Prior to the formalisation of workers into the public health system in 2011 training of CHWs and HCBC participants was mostly conducted by NPOs and NGOs in inconsistent and fragmented ways which led to a diversity of skills amongst the cohort of workers. The formalisation process sought to also align and standardise training of CHWs by providing skills development in three phases. The first two include two 10-day short courses followed by a one-year National Qualification Framework (NQF) Level 3 Health Promoter qualification

Absorption into the public service

A risk identified early on in the programme was that as the programme grew, the public health system would grow more reliant on the semi-formal and semi-integrated workers employed through the EPWP and avoid addressing the structural problem of limited supply of health professionals in the sector

The move has created tension in the sector from two opposing perspectives. On the one hand organised labour has mobilised protest efforts in other provinces to demand that they follow in Gauteng’s example

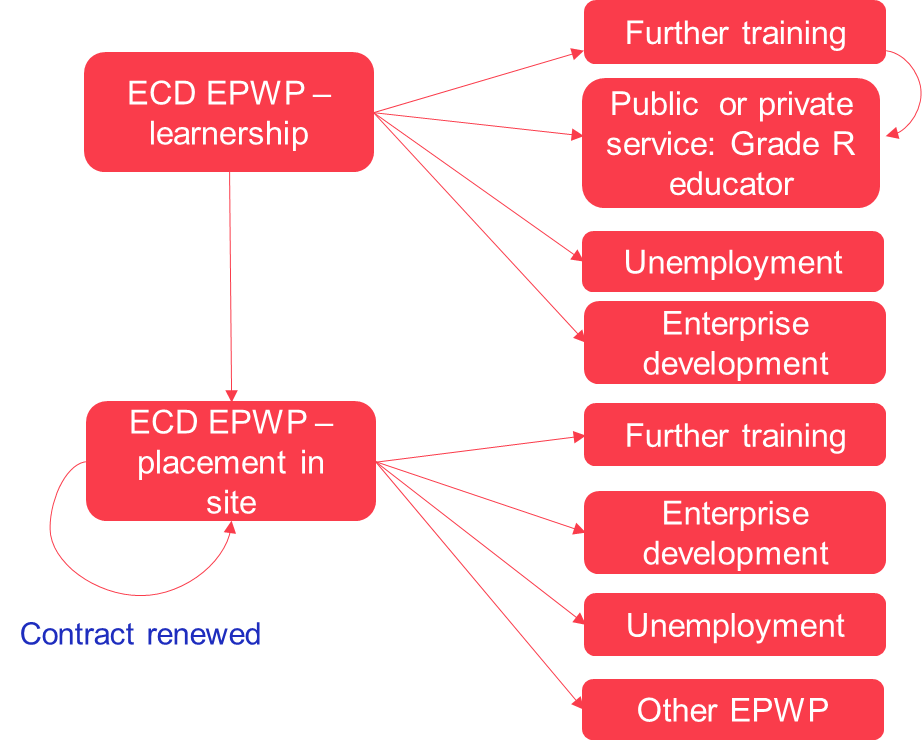

Early Childhood Development

Figure

Training

The DBE’s programme is an important training delivery mechanism within EPWP. Together with the Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs), the provincial education departments’ work opportunities are learnership for training at TVET colleges. A challenge within this programme is the poor supply of training programmes in colleges and few higher education institutions that offer qualifications in ECD for the 0 to 4 age group

Enterprise development

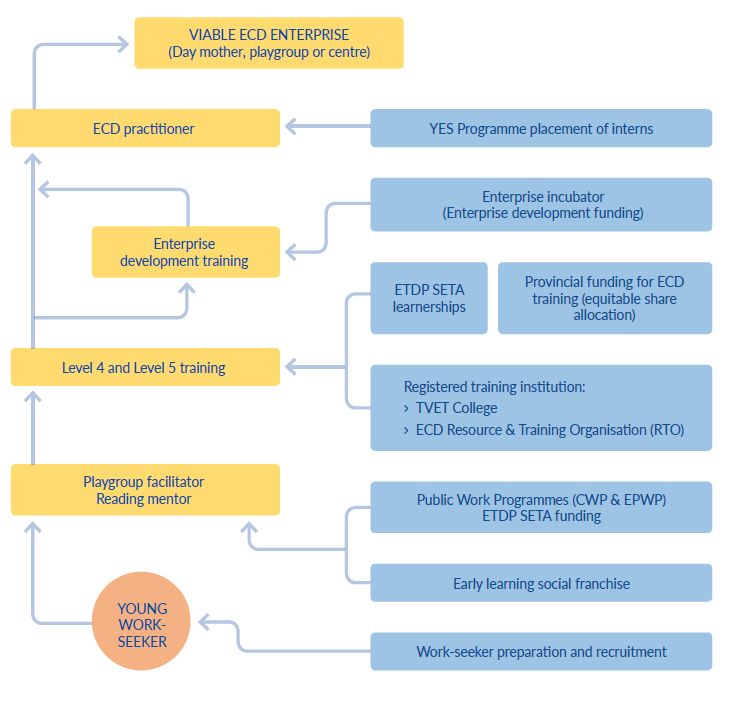

Social franchising is a recent model of delivery that is finding traction within the ECD sector that also offers a pathway for both scaling the provision of care services as well as opportunities for participants to exit into

Ilifa Labatwana and Kago ya Bana’s vision for ECD maps out this a pathway explicitly in

Figure

Source:

The pathway draws on a wider array of stakeholders to contribute to the scale up of ECD services and create sustainable employment opportunities. The public sector contributes training funding and creates PEPs work opportunities, the private sector invests in workplace-based experience (through the Youth Employment Service) and non-profit organisations deliver ECD services. A young work seeker is envisioned to enter the sector through a recruitment process into a PEPs as a playgroup facilitator or reading mentor, then receive ECD training and enterprise development training and moving into an internship placement as an ECD practitioner in an existing centre before establishing their own ECD enterprise. Qualified ECD practitioners could also enter this pathway through PEPs work opportunities in existing centres and transition into running their own enterprises after receiving the enterprise development training. This pathway therefore positions PEPs as a critical entry point into the ECD sector and the first employment opportunity that lays the foundation for a young work seeker to transition into sustainable employment opportunities.

Absorption into the public service

The cases where ECD practitioners transition into public service jobs is through securing jobs in the public sector as Grade R teachers after completing all the levels of training required. These positions are permanent and afford these participants all the benefits associated with decent care work. This transition is a preferred option for many participants that qualify with some also opting for opportunities in the private sector

The NSNP’s food handler opportunities are designed as one year contract with communicated expectations that these are shared opportunities within the community

National School Nutrition Programme

As previously discussed, this programme is designed as short term and has largely created clear expectations with participants that the opportunities are rotated within the community.

Figure

Training

The training for food handlers largely focuses on skilling them to perform their roles to the standard required. These participants are required to receive training on health and safety and food preparation prior to commencing work. School districts are responsible for conducting this training. An evaluation of the programme in 2016 found that with less than half of this cohort trained, many provinces were failing to complete the requisite training of food handlers

A debate within and outside of EPWP as it entered its fourth phase was how training should be incorporated given the continuous struggle with realising all the objectives. The phase four strategy shows the evolution clearly in that training is positioned a non-compulsory but highly desirable element of the programme that should be implemented where needed depending on the availability of funds

Enterprise development

A pilot programme within the Social Sector when enterprise development was a core priority was the training of local women as food handlers in the NSNP and then assisting them to transition into food service providers within co-operatives

The contribution of EPWP to the care economy

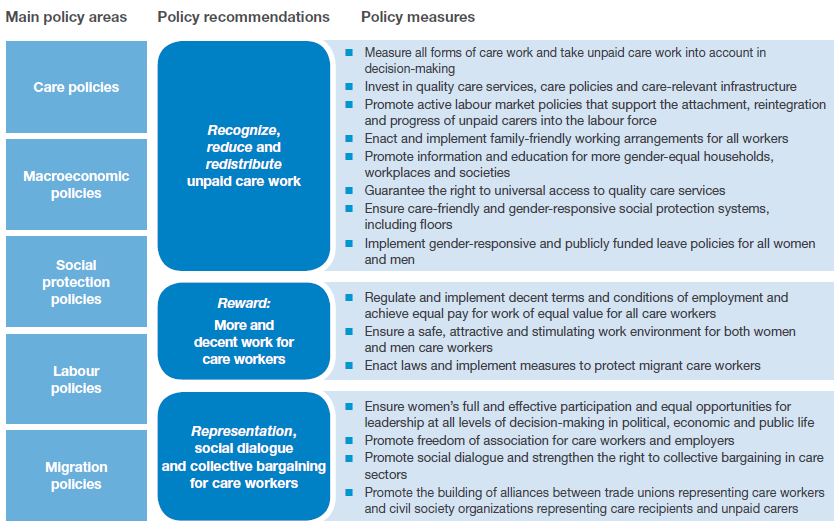

EPWP has experienced numerous challenges since its inception however, the programme has also made notable contributions to the care economy, particularly in the early years of its implementation. The ILO’s 5R Framework for Decent Care Work is useful for outlining these. The framework outlines the main policy areas and measures that can be implemented to realise decent care work.

Figure

Source:

Based on this framework, the EPWP’s contribution has been to recognise, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work and improve working conditions for existing workers. The programme facilitated the significant scale up of the HCBC and ECD programmes early in the programme and within the NSNP in later years. Furthermore, it has contributed to the creation of a new floor in terms of both wages and conditions for participants that were previously working as volunteers in the sector

The introduction of EPWP enabled a comprehensive response to the HIV/AIDS crisis by facilitating a rapid growth in the number of lay workers recruited to offer primary health care services in communities

Similar benefits are observed in the response to the tuberculosis epidemic where trained lay people employed through the EPWP have and continue to assist with a range of duties helping to relieve the nurses to do clinical work. It is generally accepted that the success of interventions implemented to curb the effects of the of these epidemics would have been limited without the participants employed in the EPWP

In terms of the three components of the programme’s objectives i.e., employment creation, income support and the development of community assets and service provision, the above highlights that EPWP has been able to contribute two of these namely employment creation and provision of services. Additionally, EPWP’s contribution has been the decision to experiment with PEPs in the care economy and through implementation, build a body of knowledge and experience that has created a foundation from which to refine the existing programmes and build new ones.

This section has provided a comprehensive historical overview of PEPs in the care economy. These programmes have created a crucial mechanism for expanding the workforce in the care economy and the wage and working conditions initially yielded desired labour market outcomes. The experience is, however, not homogenous across the three main programmes. The NSNP has largely been designed and implemented as a short-term opportunity and community social protection mechanism that is embedded within the school system. The problems with PEPs in the care economy are most prevalent within ECD where they persisted throughout the implementation period. Compounded by the continued dominance of service provision by informal operators with severe funding constraints that has maintained precarious forms of work and low wages in the sector. The healthcare sector has recognised the challenges with several examples of a slow, but progressive shifts towards decent work for CHWs in the sector, first through formalisation and more recently through absorption in the public service. Overall, a mixed bag of results that suggests that PEPs in their current form are not comprehensive or appropriate for all types of care services. If maintained, a set of measures are required to address the shortcomings.

The above was the state of PEPs in the care economy prior to COVID-19 which has severely disrupted each of the programmes. The next section outlines the main effects of COVID-19 on the care sectors in the country and the following describes how PEPs have been built into the design of the country’s response to the effects of COVID-19.

Support measures for the care economy

An urgent need to respond to a health crisis that required delivery of care at scale was one of the motivations for including the care economy in the design of EPWP. As South Africa faces another epidemic that has resulted in a rapid rise in the demand for care while introducing new challenges to the health and economic landscape, the country has had to draw on solutions that have demonstrated success in the past and adapt existing strengths to respond to the health and economic crisis in an optimal and appropriate manner. Although the perception of PEPs may be mixed, there is broad agreement that the fight against HIV/AIDS relied significantly on these programmes’ ability to augment the existing health workforce and connect communities most in need of care with the health system. As a result, part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic is the use of PEPs in the care economy to contribute to the health and economic recovery. The support measures are being delivered through EPWP and a new Presidential Employment Stimulus package, both discussed below in more detail.

Care related support in EPWP

The DPWI reprioritised R771 million of its EPWP budget to recruit 25 000 participants that would support the health department in the COVID-19 response. The department entrusted the recruitment of these participants to the Independent Development Trust (IDT) and transferred R234 million for this purpose. The advantage of using the IDT was the potential for faster implementation as it already has contracts with NPOs in place as part of the implementation of EPWP in the non-state sector. At the end of June 2020, only R26 million of the R234 million had been spent and it is unclear how many participants were recruited

Additionally a directive was issued from the Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure for all EPWP participants that were enrolled in programmes prior to the lockdown to continue to receive wages during the lockdown which is another form of support for those programmes in EPWP that are part of the care economy however, it is unclear how many of the workers were actually paid

Care related support in the Presidential Employment Stimulus package

On 21 April 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a R500 billion (approximately USD 32 billion) economic stimulus package, with R100 billion being tentatively set aside for a Presidential Employment Stimulus package (PES) to forge a new economy. The PES is being facilitated and coordinated by the Project Management Office in the Presidency and comprises three complementary dimensions:

-

Create social employment through expanding public employment through new and innovative mechanisms that draw on implementation capacity beyond the state.

-

Invest in public goods and services through expanding traditional public employment programmes to reach greater numbers while contributing to the delivery of improved public goods and services.

-

Enable private sector recovery and dynamism through prioritising growth-enhancing reforms in areas of the economy with a high potential for employment creation and gearing them for future sustainability.

Within the three dimensions of the employment stimulus identified above, twelve priority interventions have been identified that could be implemented in the 2020/2021 financial year as part of the immediate response to COVID-19.

Table

|

|

|

|

Create social employment |

Activate the wider society to create work that serves the common good |

|

Invest in direct employment through the public sector |

Activate the wider society to create work that serves the common good |

|

Unlock employment in the wider economy |

Unlock digital access and inclusion |

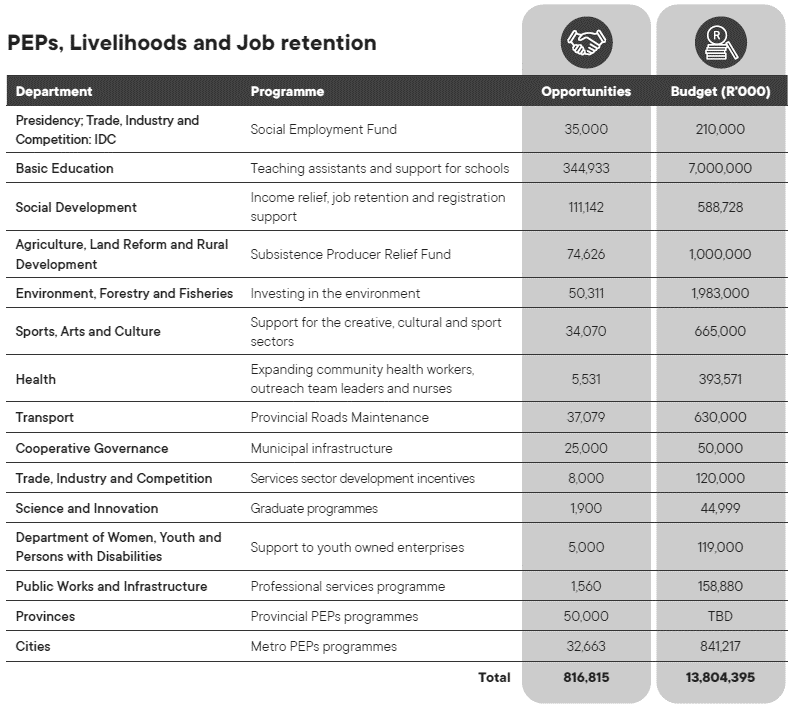

On 24 June 2020, the Minister of Finance, Tito Mboweni, announced a provisional allocation of R19.6 billion to the PES in the Special Adjustment Budget for the 2020/21 financial year

The President announced phase 1 of the Presidential Employment Stimulus as part of the country’s Economic Recovery and Reconstruction Plan in a joint sitting of parliament on 15 October. Appendix A2 provides an overall summary of all the programmes in the PES. Of the R19.6 billion, R12.6 billion was approved for allocation to 11 national departments in the first round. The proposals submitted in the second round were all not approved for funding following a decision to use the remaining R7 billion to fund an extension of the Special Relief of Distress (SRD) COVID-19 grant by another three months

Table

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic Education |

Teaching assistants and support for schools |

Classroom assistance in all schools with priority given to no-fee schools. Cleaning, screening of learners and job retention at Q4, Q5 and low fee private schools. |

One

|

344 933 |

7 000 000 |

|

Social Development |

Income relief, job retention and registration support |

Grant to Early Childhood Development (ECD) related workers for six months. Retention social workers and recruit registration support officers. |

One |

111 142 |

588 728 |

|

Health |

Expanding community health workers, outreach team leaders and nurses |

Recruitment of outreach team leaders (OTL), community health workers (CHW), enrolled nurses and auxiliary nurses. |

One |

5 531 |

393 571 |

|

Trade, Industry and Competition |

Social Employment Fund |

A new instrument to support the wider society to engage people in useful work that addresses social challenges and generates community agency and partnerships. |

Two |

35 000 |

210 000 |

|

Metropolitan municipalities |

Several programmes |

Addressing the social care needs of the homeless in City of Cape Town and eThekwini metropolitan municipality, support for the social development and primary health division in Ekurhuleni metropolitan municipality |

Two |

650 |

23 449 |

Source:

Overall, the care related programmes that received funding constitute R8 billion which is 67% of the total funding for the stimulus. These programmes fall into three broad categories of support: (1) direct investment through public employment programmes, (2) financial support to retain jobs and (3) transfers to support livelihoods. While the intervention options all contribute to employment outcomes directly or indirectly, they did not all necessary seek to create direct new jobs. This is demonstrative of the responsiveness of the employment stimulus to the different needs in the various sectors in acknowledgement of the differentiated effects of the pandemic on each one.

Unfunded proposals

As discussed above, the proposals submitted in the second funding round for Phase 1 of the stimulus were all not approved for implementation to accommodate an extension of the SRD grant and not because of reasons related to the merits of the proposals. These proposals are briefly discussed below.

Social Employment

The social employment fund is one of the innovative elements in the stimulus package. Designed as a new form of public employment, this programme creates a new grant making instrument for government to draw on the wider society, through mostly non-profit organisations, to create work for the common good. At its core, the strategy acknowledges the fact that there is no shortage of necessary and useful work in communities and what is required is an effective mechanism to fund and recognise this work.

The aim of this approach is to unlock new forms of partnership across a range of different stakeholders that build agency and support community driven initiatives while generating direct benefits for the participants. The opportunities are designed to be part-time offering a regular and predictable source of income, work experience and the ability to build new networks with the intention to improve participants’ chances of exiting into other opportunities.

The Industrial Development Corporation, an entity of the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, will be the fund manager in line with the department’s mandate to support job creation in the social economy. Although this proposal did not receive funding in the Phase 1 of the stimulus, work is ongoing to establish strong institutional arrangements, finalise a comprehensive design and prepare for a first call of proposals that seeks to pilot the initiative using other sources of funding before scaling the intervention in the medium term should funding for Phase 2 of the stimulus be approved.

Cities proposals

The Cities Support Programme facilitated a process for the metropolitan municipalities to submit proposals for the PES. Cities were required to identify opportunities to scale up successful EPWP programmes, introduce innovation in the delivery of services and create new forms of partnership. A multitude of projects were submitted and approved, a few of which targeted the care economy for support. These include two projects focused on care for the homeless in the City of Cape Town and eThekwini metropolitan municipalities respectively as well as a proposal in Ekurhuleni metropolitan municipality to provide support such as data capturing, cleaning, and other services to primary health care project. The projects for the homeless were designed to recruit 500 and 150 participants respectively in each municipality to assist in the rehabilitation of people back into society. The project in Ekurhuleni sought to recruit 750 young people in clinics to perform duties such as record keeping, cleaning, data capturing, and registration of patients on the electronic health system. This funding was directed at augmenting the budget of an existing EPWP project that had been cut.

Funded basic education proposals

The approved proposals from the DBE include the recruitment of education assistants, general assistants and funds to fee paying schools to retain jobs of teachers. The first two largely allow for a programmatic response to the challenges facing schools and provide for nationwide coverage with a bias towards schools serving poor children while at the same time providing employment opportunities for young people. Together, the education and general assistants programme is the single largest public employment programme in the country.

Table

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education assistants to provide classroom assistance in all schools. Allocation favours no-fee paying schools. |

200 000 |

4 200 000 |

|

General assistants |

Janitors, screeners, cleaners, and other types of support required by the school. |

100 000 |

1 800 000 |

|

Job retention |

Saving jobs at quintile 4 and quintile 5 schools (School Governing Body posts) as well as low fee private schools where parents have not been able to pay school fees due to lockdown |

44 933 |

1 000 000 |

|

|

344 933 |

7 000 000 |

Source:

Education assistants

The Department of Basic Education intervention seeks to address two challenges: the problem of large class sizes and the effect thereof on the quality of learning in schools and youth unemployment. Teachers in poor schools face a burden as their teaching load is significantly larger and has to be balanced with other activities such as extra-curricular activities and provision of support to learners. This problem has been exacerbated during the pandemic which has added new responsibilities to teach more classes and take on responsibilities to ensure learners adhere to safety and hygiene requirements. Moreover, youth unemployment has increased as a result of the effects of the pandemic on the economy and is expected to worsen

Through a focus on the recruitment of young people, this intervention will provide schools with education assistants who will primarily provide classroom and administrative support to teachers. The intervention will see a total of 200 000 young people recruited in all schools across the country to provide education support to teachers. Initially proposed to cover only quintile 1 to 3 schools, the intervention was later extended to cover all schools with the justification that the COVID-19 pandemic had led to new administrative burdens in quintile 4 and 5 schools as well. The specific duties will differ in each school, however, support is generally envisaged to include the preparation of the classroom prior to teaching and learning, preparing mark sheets and capturing, assisting with managing behaviour in the classroom and any other administrative tasks that the school identifies.

General assistants

Prior to schools re-opening in June, the DBE assessed the readiness of schools to re-open and identified a human capacity gap to perform the tasks required to comply with measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 in schools. The education infrastructure conditional grant was augmented to allow the school management to recruit janitors, screeners, and cleaners in preparation for the re-opening and maintaining daily cleaning and hygiene requirements

This intervention is an extension of this support and targets the recruitment of 100 000 young people in quintile 1 to 3 schools as general assistants to allow schools to, amongst other needs, continue deep cleaning and screening of learners. The intervention is designed with flexibility to allow the school management to respond to their specific needs. For example, some schools may require assistants to perform safety related duties or minor maintenance. The decision on the specific duties to be performed is at the discretion of the school governing body.

Job retention

Quintile 4 and 5 public schools receive relatively lower per child transfers relative to quintile 1 to 3 schools. Hence, to augment funding, these schools charge school fees which are used to also fund additional teacher’s posts. These posts are created by the school governing body and are not government posts through the provincial department of education. In the wake of the pandemic, many parents and guardians ceased to pay fees during the lockdown while learners were at home creating financial pressure on schools. This experience is also shared by government subsidised low fee independent schools that are heavily reliant on parent fees. As a result, many of the schools in these categories have experienced severe loss of income that has placed some of the posts funded from these fees at risk.

This intervention seeks to save 44 933 teachers’ jobs in school governing posts (i.e., those funded by the school and not through the provincial department of education) and those in government subsidised independent or private schools. Each provincial department is required to design eligibility criteria, with guidance from the national department, to determine which schools will be supported.

Funded early childhood development proposals

The Minister of Social Development, Ms Lindiwe Zulu, announced in a sitting of the portfolio committee on 30 July that the department would allocate R1.3 billion from the stimulus towards the employment of 36 000 youth as compliance monitors in ECD programmes. The announcement and the proposal from the department drew strong criticism from the ECD sector for ignoring the plight of ECD providers and the workforce with some in the sector arguing that this allocation can and should be used to save 176 000 jobs

A revised proposal was then submitted in the budget adjudication process to respond to the sector’s call for financial relief. A final amount of R513 million was approved for a set of interventions including income support for the ECD workforce, compliance support and the appointment of registration support officers.

Table

|

|

|

|

|

|

ECD income relief |

Income relief in the form of a grant to Early Childhood Development (ECD) related workers for six months |

83 333 |

380 000 |

|

ECD compliance support |

Top-up payment to already employed ECD workers to take on compliance duties |

25 500 |

116 250 |

|

ECD registration support |

Recruitment of registration support officers to assist unregistered ECD programmes to undergo registration |

500 |

16 500 |

|

|

|

|

Source:

Income relief for ECD workforce

The temporary closure of early childhood development programmes during the lockdown has had severe financial consequences for ECD programmes. Despite ECD programmes being cleared to re-open in July when the country shifted to alert level three, many providers have still not re-opened in November due to an inability to comply with the COVID-19 regulations and conditions for re-opening. Moreover, those that have re-opened have not returned to pre-lockdown levels of operation as only few parents have allowed their children to return. The effect is continued pressure on ECD providers who continue to face risk of closure placing their workforce at risk of unemployment.

The income relief component of the interventions for the ECD sector seeks to assist ECD programmes to maintain operations, reduce the risk of permanent closure, and provide temporary relief to the ECD workforce

The support is targeted at 83 333 existing ECD workers who have lost income as a result of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. All workers in ECD programmes are eligible to benefit from the support and it is not limited to practitioners resulting in coverage of both direct and indirect care workers in the sector. Based on the budget allocation, each worker is eligible to receive the equivalent of R760 per month for six months

The design of this intervention had to consider legislative barriers with respect to providing support to unregistered centres. The Children’s Act prohibits the provision of ECD services by programmes that are not registered and hence any support from the state to such programmes would be in contravention with the Act. To overcome this, the Department of Social Development’s proposals included the issuance of specific directions within the Disaster Management Act of 57 of 2002 to create the legal conditions to temporarily support unregistered programmes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, because these programmes are not registered, they do not exist on any national information database and therefore, a clear communication plan will be required to target and communicate the support to them

As highlighted in the discussion on the effects, the negative labour market shocks in the sector have disproportionately affected women and rippled throughout the economy as many workers have had to take on more childcare responsibilities. The support provided in this sector therefore has a pivotal role to support women and accelerating the economic recovery

Compliance support

With children returning to ECD programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic, programme sites are required to comply with regulations and adhere to the prescribed measures to limit the transmission of the virus at centres and facilities. ECD programmes are required to adhere to, amongst others, the following to re-open and maintain operations:

-

Prepare own procedures that reflect changes made to daily routines to comply and display them on walls

-

Prepare letter and communicate procedures and conditions to parents

-

Daily cleaning of the physical space, teaching and learning materials

-

Adaptations to the space to allow children and adults to maintain a distance of at least 1 meter

-

Equipping the facility with a basic first aid kit, additional cloth masks and run

-

Daily screening

ECD programmes therefore require additional resources and human capacity to meet these measures. This component of the intervention responds to this need through a top up to existing employees’ income to enable them to take up additional duties to ensure compliance to the measures designed to reduce the effect of COVID-19.

The support is targeted at 25 500 existing ECD workers who will be required to take on additional responsibilities to ensure the ECD programme complies with the COVID-19 regulations to limit transmission and ensure the safety of children. Based on the budget allocation, each worker is eligible to receive the equivalent of R760 per month for six months. An important difference between this intervention and the original proposal announced by the Minister is that instead of recruiting new compliance monitors, this intervention redirects the funds to the existing workforce in the sector.

Registration support

On 2 June 2020, the Department of Social Development launched the Vangasali campaign as part of child protection week. Phase 1 of the campaign was aimed at identifying all ECD programmes that are operating without a registration certificate while Phase 2 is linked to the rollout of the ECD Registration Framework and achieving mass registration of ECD programmes. It is targeted at currently unregistered programmes to ensure that these comply with the provisions of the Children's Act 38 of 2005. Such registration would also allow the qualifying programmes to become eligible to receive financial support in the form of the subsidies component of the ECD conditional grant or the infrastructure component if they are only conditionally registered.

To support the department’s registration massification plans, this component of the stimulus seeks to recruit 500 registration support officers to provide guidance to unregistered ECD programmes in the preparation and submission of their applications for registration. The officers are also responsible for identifying barriers to attain registration so that DSD can intervene with the necessary support. The work opportunities will target unemployed young people with social service qualifications.

Funded health proposals

Table

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community health workers and outreach team leaders |

Recruitment of outreach team leaders (OTL) and community health workers (CHW) |

3 250 |

213 371 |

|

Enrolled nurses and auxiliary nurses |

Appointment of enrolled nurses and auxiliary nurses |

2 281 |

180 200 |

|

|

|

|

Source:

Community health workers and outreach team leaders

This intervention seeks to augment the community outreach services component of the HIV/AIDS grant and address shortfalls currently experienced by the department. Despite reprioritisation of resources to respond to the demand for additional workers, the DoH continues to face constraints.

A particular challenge highlighted is the limited supervision that is available to CHWs which affects the quality of care provided and support received by CHWs. The allocation to the DoH directly addresses this challenge with a plan to recruit 2 000 Outreach Team Leaders (OTLs) to provide supervision and support to CHWs. The OTLs are enrolled nurses that will allocate tasks, manage the work of CHWs and report on performance and outcomes. In addition, the department will also recruit and train an additional 1 250 CHWs to meet the shortfall.

While the above will assist to bring the DoH closer to what is required to offer a comprehensive primary health care service nationwide, the gap remains substantial. Two challenges prevented a more significant effort to scale up the programme. Firstly, the recruitment, selection and appointment processes are time consuming and take place in a highly unionised environment, as many CHWs are part of unions, which can cause significant delays. Secondly, the department currently faces financial constraints that limit the recruitment of the full staff complement of health workers (including CHWs) that are required to deliver on the mandate for community outreach services. The sector has experienced ongoing protests from this cohort of workers who demand permanent jobs. In light of the funding constraints and the pressure from CHWs for permanent jobs, offering a significant number of short-term opportunities with no guarantee for longer term opportunities comes with the risk of creating expectations from more temporary workers and further exacerbating the problem.

Enrolled and auxiliary nurses

A shortfall of professional staff in facilities across the provinces is further impacting on the health response to community health care needs. This component of the stimulus will ensure the recruitment of 1 045 enrolled nurses and 1 236 auxiliary nurses and seeks to strengthen the provision of COVID-19 related and other care services to communities. Provincial departments will recruit the nurses on short term contracts and remunerate them at existing levels in public health facilities to perform functions in line with their qualifications as well as the specific needs of the facilities.

Cross-cutting challenges with achieving scale

The stimulus package was designed to reach as many participants and beneficiaries as possible, however, several challenges were encountered that limited the scale of support provided within the care economy. The challenges that are specific to a particular programme have already been discussed above. This section provides an overview of challenges that applied to all the programmes.

The first important challenge stems from the conditions attached to the funding which include that it has to be spent by the end of March 2021 and excludes any roll over of unspent funds. The main implication was implementation timeframes of maximum six months from October which when departments received their allocation letters. This timeframe covers planning, preparation, recruitment, procurement of required equipment and services and the completion of work or transfer of subsidies. The departments were therefore required to prepare to work under extraordinary pressure to ensure participants are appointed and trained early enough to maximise the benefits of the work opportunities and accelerate the release of support for livelihoods. These timeframes had the consequence of limiting departments ambition when setting targets. While many have stretched their capacity, this was done with caution to account for what their existing capacity, processes and systems could accommodate. The most ambitious of the programmes remains the DBE school assistants programme with a target of 300 000 new work opportunities created within a six month period.