Preferential tax regimes for MSMEs

Operational aspects, impact evidence and policy implications

Abstract

Drawing on a literature review, this paper looks at the role that preferential tax regimes (PTRs) for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) play in encouraging enterprise formalization and enterprise growth. The main focus is on emerging economies, notably from Latin America, where this policy has been more widely used and assessed. The first section of the paper introduces some general principles in small business income taxation which help set the context of PTRs for MSMEs. The second section explains the main reasons in favour and against PTRs for MSMEs. The third section introduces a typology of PTRs for MSMEs, focusing on the operational aspects of the two most relevant types in emerging economies: presumptive regimes and small business tax rates. The fourth section discusses the existing empirical evidence on the impact of presumptive regimes on enterprise formalization, enterprise growth and so-called “threshold effects” (when companies avoid growing not to lose preferential taxation). The fifth section draws the main policy messages, while conclusions summarise and put forward some future research ideas.

Introduction

Taxation is at the core of the life of a business. The rate and way enterprises are taxed affect people’s propensity to start and close a business; business investments and, accordingly, business growth prospects; the decision of business owners to declare, fully or partly, their business income and to incorporate or not their own enterprise; or still the preference of entrepreneurs for certain sectors rather than for others, if sectors are not taxed effectively so as to minimize resource misallocation.

Intuitively, high business taxation has negative effects on entrepreneurship and business investment, although estimates on the magnitude of these effects differ significantly (for a review of the literature, see Hasset and Hubbard, 2002). Furthermore, higher corporate taxation is associated with a larger informal sector, greater reliance on debt as opposed to equity finance, and lower investment, especially in manufacturing (Djankov et al., 2010). By way of example, Wasem (2018) reports how the introduction of a law in Pakistan that increased taxation for partnerships prompted more companies to report lower earnings, change type of legal entity or simply move into the informal economy. It is not just the tax rate that matters but also the way in which businesses are taxed. In particular, low compliance cost for business, certainty and simplicity of tax rules, and low administration costs for the government all matter in making the tax system friendly to businesses and easy-to-manage for tax authorities. For example, a recent study found that a reduction in the administrative tax burden by 10% leads to a surge in entrepreneurial activity by nearly 4% (Braunerhjelm et al., 2019).

This paper draws on a review of the literature to examine what role a specific type of small business taxation, i.e. preferential tax regimes (PTRs) for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs)1 , play in encouraging enterprise formalization and enterprise growth2. Enterprise formalization is defined here as the process by which an informal (unregistered) enterprise registers in the national business registry and/or submits an annual income tax declaration, which are the two most commonly used definitions in the reviewed literature3.

Before moving forward, it is important to note that taxation is just one of the possible drivers of enterprise formalization and that successful formalization strategies are rather the outcome of both strong business environment conditions and a broad set of institutional policies that include but go beyond taxation. For example, in the context of Latin America, the ILO found that in the period 2002-2012, changes in the economic structure explained 60% of the reduction in informality, while public policies accounted for the remaining 40% (Infante, 2018)4. Formalization policies will encompass tax simplification and tax incentives, including through PTRs for MSMEs, but also regulatory reforms, productivity policies (e.g. sector and value chain development, skills upgrading and innovation promotion at the firm level), and improved law enforcement (e.g. labour inspections and culture of compliance). While most empirical studies look at the impact of one single policy on formalization outcomes, something which is reflected in our literature review, better results in terms of formalization can be expected if governments adopt a multipronged strategy that combines different policy approaches together (Chacaltana and Leung, 2020)5.

Against this backdrop, the paper proceeds as follows. The first part briefly introduces the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated enterprises. The way these two legal entities are taxed is different and affects, among others, the access by MSMEs to PTRs. The second central part of the paper delves into PTRs for MSMEs and discusses their policy rationale, a typology, and evidence about their impact (especially presumptive regimes) on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth. Based on the operational aspects and evidence discussed in this second part, the paper draws the main policy takeaways for policymakers interested in introducing or reforming PTRs for MSMEs as part of their national formalization strategies.

Box

Enterprise formalization and enterprise growth are the core of the work and mandate of the International Labour Organization (ILO). The “Conclusions concerning the promotion of sustainable enterprises” of the 2007 International Labour Conference (ILC) prioritised an enabling legal and regulatory environment and fair competition to promote sustainable enterprises, both of which imply sound tax policies. Beforehand, Recommendation 189 of the 1998 ILC stated that governments should create conditions that provide all enterprises, regardless of their size and legal type, with access to fair taxation.

The formalization of the economy is one of ILO’s priorities, as stated in Recommendation N. 204 of the 2015 ILC, which reiterates the importance of a conducive business environment and strong MSMEs to reduce the size of the informal economy. In particular, Recommendation N. 204 put forward a formalization policy framework that hinged on three main objectives: a) formal business and employment generation; b) policies to facilitate the transition from the informal to the formal economy, c) policies for preventing the “informalization” of formal jobs.

Taxing small business income: the difference between incorporated and unincorporated enterprises

An important distinction in the taxation of small business income is that between incorporated and unincorporated enterprises6. Incorporation is the legal act by which a different legal entity, called corporation, is established to separate the assets and income of the company from those of the owners and investors. The first advantage of creating a corporation is that only the assets and income of the corporation can be legally seized – for example, in case of bankruptcy, insolvency or loan default – while those of the owners and investors are legally protected from creditors’ claims. In addition, corporations can change ownership and raise capital more easily through the sale of stocks. On the downside, the establishment of a corporation involves more administrative procedures and is more costly in terms of registration fees and paid-in minimum capital requirements7. For example, research finds that minimum capital requirements reduce the rate of business creation across countries (van Steel et al., 2007) and that such requirements are proportionally (i.e. relative to national GDP) higher in low-income countries (World Bank, 2014). Bookkeeping and corporate governance requirements are also on average more demanding for incorporated businesses than for unincorporated businesses.

Taxation also helps explain why many low-income small business owners prefer not incorporating their enterprise. In the case of unincorporated business entities, business owners are only subject to personal income taxation (PIT), whereas owners of corporate entities are subject to “double taxation”: corporate income taxation (CIT) on taxable profits and second-level taxation on the share of business income that is distributed to business owners and shareholders8. Furthermore, PIT marginal rates that apply to low-income earners, who generally include the self-employed and micro-enterprise owners, are typically lower than the national statutory CIT rate9. Frequent PIT exemptions and Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) for low-income earners add to the fiscal advantage of placing sole-proprietorship and micro-enterprises within the legal framework of unincorporated enterprises10.

However, as business income grows, the case for incorporating becomes more compelling. First of all, as noted earlier, only the assets and income of corporations are subject to creditors’ claims. This provides an important safety net for entrepreneurs operating larger and/or growing businesses that may require larger loans than those demanded by micro-enterprises and that are more likely to engage in riskier activities such as exporting and innovation. Secondly, the statutory CIT rate is typically lower than the highest PIT marginal rates, which means that companies with healthy balance sheets are likely to be better off within the corporate tax regime. For instance, across OECD countries for which data are more readily available, the median statutory CIT rate was 21.7% in 2019, while the median 3rd and 4th PIT marginal rate (from the bottom of the income scale) were respectively 26.5% and 34%. This suggests that corporate income taxation is nominally more advantageous than personal income taxation already at relatively low levels of annual income11. If national legislations also foresee a preferential tax regime for incorporated MSMEs, what we call here a “small business tax rate”, the fiscal advantage of incorporation becomes even larger. Thirdly, national legislations are more likely to offer investment tax credits and loss carry-forward provisions to corporate business entities than to unincorporated enterprises, both of which reduce the effective CIT rate below the nominal one12. Finally, while it is true than the share of corporate income distributed to business owners is subject to second-level taxation (i.e. double taxation), national legislations typically include provisions to reduce the tax load, especially for MSMEs and especially if such income is distributed as capital gains or dividends (OECD, 2015)13.

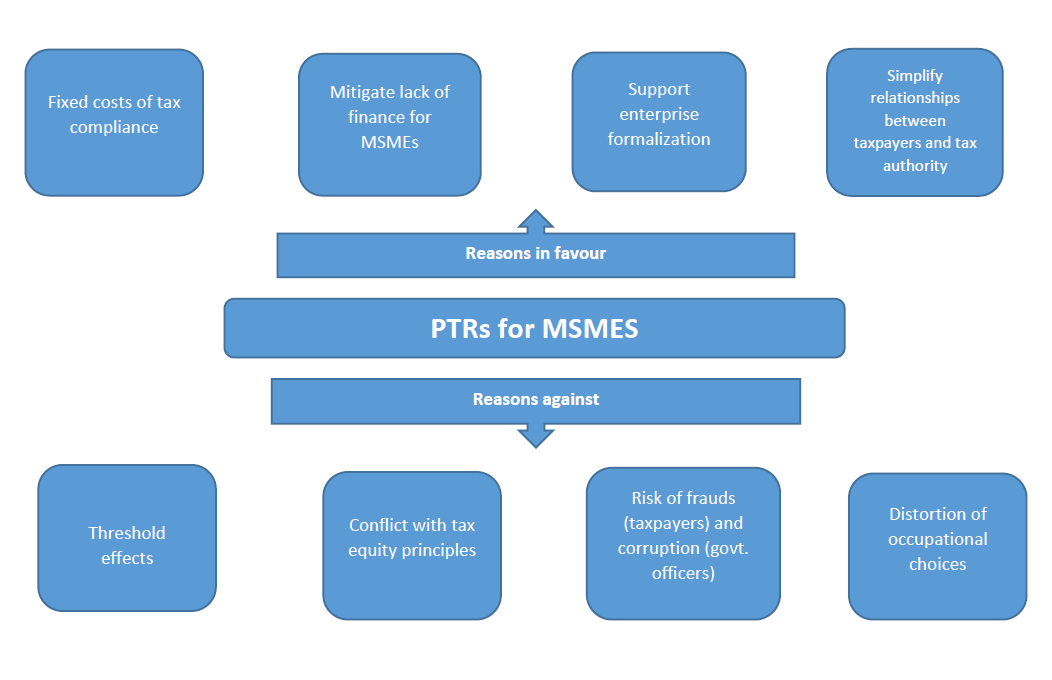

Reasons in favour and against PTRs for MSMEs

Against this general backdrop, preferential tax regimes (PTRs) are special fiscal regimes that offer a lower tax rate and simpler tax compliance requirements than the mainstream tax regime to their target group. While there are also other types of PTRs14, those aimed at MSMEs are among the most common worldwide. Several reasons explain the large use of this policy.

First of all, tax compliance comes with fixed costs, making it proportionally more expensive for MSMEs than for larger companies. Indeed, while total tax compliance costs are higher for larger companies in absolute terms, they are more burdensome for MSMEs when they are measured in relation to sales. A study from South Africa finds, for example, that companies with annual turnover up to ZAR 245,000 pay on average 4.7% of their annual sales to outsource tax payment to professional consultants and 3.1% to do the same with payroll duties. These figures drop to 1.4% and 1.9% for companies with annual turnover between ZAR 245,000 and ZAR 525,000, and become almost insignificant (0.3% and 0.1%) for companies with annual turnover above ZAR 3 million (Smulders et al., 2012). Governments may, therefore, decide to use PTRs for MSMEs to help them deal with higher-than-average tax compliance costs, thus levelling the playing field with larger companies.

Second, it is also well known that MSMEs find it more difficult than larger companies to receive external finance (Beck et al., 2008). For example, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates that 40% of formal MSMEs, corresponding to 65 million firms, have unmet financing needs of 5.2 trillion US dollars every year, which is equivalent to 1.4 times the current level of global MSME lending. Moreover, about half of formal MSMEs do not have access to formal credit, with the financing gap getting even wider if informal enterprises are taken into account15. Against this backdrop, preferential taxation reduces the need for MSMEs to obtain external finance by helping them retain a higher proportion of earnings. While addressing an enterprise financing problem through tax policy is not orthodox policy16, this approach helps policy makers to mitigate a problem that otherwise requires much longer time to fix.

Third, by the virtue of reducing the tax burden, preferential tax regimes, especially presumptive regimes (see following section), provide an incentive for some self-employed and micro-enterprises to operate in the formal economy. Participation in the formal economy can eventually trigger other productivity-enhancing dynamics, notably through access to larger markets and higher-skilled workers, although this positive cycle should not be taken for granted and is more likely to happen if newly formalized enterprises are also offered other support in the form of managerial training.

Fourth, the use of PTRs can simplify tax administration, broaden the tax base (i.e. increase the number of taxpayers) and raise additional tax revenues. In particular, presumptive tax regimes are expected to simplify the relationship between national tax authorities and the host of micro and small enterprises in developing countries, although additional tax revenues collected through these regimes are generally thin17.

While these are the most common arguments in support of PTRs for MSMEs, these regimes have also faced important criticisms. One of the main allegations is that they cause “threshold effects” (i.e. also known as “bunching effects” or “growth traps”), that is to say, they create a disincentive for enterprises to grow beyond the size threshold after which the tax preference is lost. While this makes sense in principle, whether this really happens is an empirical question that research has tried to answer and that is discussed in greater detail in a following section of this paper.

A second allegation, which is closely related to threshold effects, is that PTRs for MSMEs do not respect the principle of tax equity and may therefore lead to a misallocation of resources in the economy. In particular, companies just below and just above the size threshold may be subject to a very different effective tax rate despite similar levels of income. Similarly, it is also possible that more profitable companies will pay fewer taxes than less profitable companies if the threshold is not based on income but on another variable such as turnover or employment, which is the case with presumptive regimes.

A third criticism goes under the category of frauds; for example, when large companies break into smaller entities to benefit from preferential taxation (i.e. horizontal company break-up) or when employers demand workers to register as self-employed within the framework of a presumptive regime not to pay their social contributions (i.e. disguised employment relationship). On the other side of the tax relationship, corruption among government officers in charge with tax collection is also a risk that would thwart the effectiveness of this policy18.

Finally, a less common claim is that PTRs for MSMEs distort occupational choices because more people are pulled into an entrepreneurial career even if they lack the talent and/or resources to grow their business. This thesis resonates with the more general argument that incentives for start-ups are bad public policy because they attract low-skilled people into an entrepreneurial career (Shane, 2009). While it is true that most businesses in presumptive regimes are in low value-adding sectors of the economy (e.g. personal services and retail trade), a full welfare analysis would have to consider the counterfactual situation in the absence of such a policy, which may well be higher unemployment and/or higher informality.

Figure

A typology of PTRs for MSMEs

There are at least four different types of PTRs for MSMEs. The first consists in “presumptive regimes” that enable MSMEs to calculate their tax liability based on an estimated income, where the estimation is computed based on another financial or nonfinancial indicator than income (e.g. turnover, capital assets, employment, electricity consumption, floor space). The second type consists in a discount on the statutory CIT rate, something that we call here “small business tax rate” (SBTR); for obvious reasons, this tax reduction only applies to businesses that have a corporate legal status. The third type refers to tax reductions or exemptions other than on the business income, for example on the value-added tax (VAT). Finally, the fourth type includes tax preferences that reduce the overall tax load for an MSME, such as investment tax credits or R&D tax credits or still reductions or exemptions from capital gains taxation on the sale of MSME shares. In addition to a lower tax rate, PTRs for MSMEs generally include simpler compliance requirements. The rest of this section focuses on the first two types of PTRs for MSMEs, as they are the most relevant for enterprise formalization and small business growth in the context of emerging economies19.

Presumptive regimes

Presumptive regimes are the most common form of PTRs for MSMEs and are mostly used to encourage enterprise formalization through the simplification and reduction of income taxation. Presumptive regimes are generally meant for low-income business owners, generally self-employed people or micro-enterprise owners, and work on a voluntary basis, which means that the policy does not automatically apply to the eligible population who, on the other hand, need to explicitly enrol in it. Presumptive regimes come as a package that can include two or more of the following components:

-

A simplified method of income tax calculation that uses another variable than income (“proxy variable”) as the tax base, such as turnover (revenues), capital assets, employment, electricity consumption or the floor space of the establishment (see Box 2 for further information). The use of proxy variables is due to the difficulty of establishing taxable income for very small economic units that often operate in semi-informality.

-

A reduced income tax, which can take the form of a lump sum or a lower rate on the personal or corporate income tax, depending on the legal nature of the business.20

-

Additional reductions or exemptions from other local or national taxes, such as the value-added tax, social security contributions or still production and excise taxes. Typically, this happens through the submission of a single tax form, with the tax collection that is then distributed on a proportional basis to the different tax items by the national tax authority.

-

Simplified tax compliance requirements through, for example, a reduction in the number and frequency of forms to fill over the fiscal year. Simplification may also concern other aspects such as bookkeeping requirements and online tax payment support.

-

Social protection for business owners and workers through the payment of social security contributions.

In addition, on occasion, the tax aid of presumptive regimes has also been matched with other types of support such as skills development in business administration (e.g. training and coaching) and financial support (e.g. preferential credit lines and loan guarantees).

Box 2. Which proxy variable to use in presumptive tax regimes?

In presumptive tax regimes, the income tax base is calculated based on other variables (i.e. “proxy variables”) than taxable profits. The most common proxy variable is turnover (i.e. sales revenues), although other options include capital assets, employment or still electricity consumption.

All in all, the use of turnover as proxy variable in presumptive regimes may still represent the “safest bet” in the context of low-income and lower-middle economies where national tax authorities are faced with financial and human resource constraints that make it difficult to apply more sophisticated estimation methods. On the other hand, the use of other variables such as electricity consumption could be taken into consideration in upper-middle income economies, given the difficulty of underreporting it and the positive externalities associated with the use of this variable. As to employment, its use as proxy variable is problematic due to the potential unintended effects on labour informality and short-term contractual arrangements.

Finally, regardless of the variable used to calculate the tax liability, sector adjustments are often needed given that indicators such as the profitability ratio, capital assets, employment or electricity consumption can vary a lot depending on the type of business activity. This is why it is not rare for presumptive regimes to apply only to similar business activities, such as retail trade and personal services, or to use sector coefficients to take sector heterogeneity into account.

With respect to tax payment in presumptive regimes, this can come under three forms:

-

A monthly lump sum, which is the same for all eligible companies.

-

A payment that is proportionally linked to the variable used to calculate the tax liability.

-

A tiered system in which the tax payment changes according to the sector and/or size of the company and where the tax liability is again calculated as a function of the “proxy variable”.

The first type (lump-sum regime) is typically targeted at low-income micro-entrepreneurs whose business activity does not require a professional qualification, such as in retail trade and some personal services. The main advantage of this approach lies with its simplicity. However, simplicity also comes with some drawbacks. First, the lump sum approach is fiscally “regressive”, since the same amount is collected from companies with different levels of turnover and profits. Second, the policy may become anticyclical, charging a higher effective tax rate during economic slumps due to the fixed nature of the lump sum. Third, due to its high fiscal attractiveness and low documentation requirements, this approach may become more prone to fraudulent behaviours than others.

To address these issues, eligibility conditions should be easy to verify, possibly through digitised tax systems that reduce or avoid the need for field inspections, which are expensive to conduct and prone to the opposite risk of corruption by government officers. It would also be important that eligible business owners keep simple books, as a means to strengthen financial literacy and to be able to move more easily into another tax regime if they grow. In this respect, the existence of an intermediary regime between the “lump sum” regime and the mainstream tax regime can help companies mature more progressively within the national tax system (Coolidge and Yilmaz, 2016)21. Finally, adjusting the lump sum downward at times of slowdowns and upward at times of upswings will help make this policy more pro-cyclical than in the case of a fixed sum over time.

In the second and third types of presumptive regimes, the tax levy is calculated in proportion to the “proxy variable” of income used in the scheme. The existence of a closer relationship between the tax duty and the “proxy variable” makes this approach less fiscally regressive than the lump-sum method, something which is even more pronounced in the case of a tiered system in which the tax rate changes depending on the sector and/or enterprise size. Generally speaking, a rate-based approach can also make the transition to other tax regimes easier. The main downside of this approach is its complexity, especially in the case of a tiered system, which makes it more difficult to implement for resource-constrained national tax authorities.

The following examples present two case studies of presumptive regimes from Brazil (

Box 3. Brazil's presumptive tax regime for micro-entrepreneurs (

Since 2009 Brazil has operated a presumptive tax regime called

The main tax benefits of MEI are as follows:

-

A fixed monthly payment to cover local taxes at the state and municipal levels;

-

Exemptions from federal income taxation and other federal taxes;

-

Social security contributions set at 5% of the minimum wage;

-

If the business has an employee, the micro-entrepreneur must pay 3% of his/her remuneration to the social security system, while 8% of the gross wage is deducted to finance an unemployment insurance programme called “Guarantee Fund of Work Time”.

-

Taxes are paid monthly, with the possibility to pay online.

As of May 2020, 9.8 million enterprises were operating under the MEI regime, out of a total of 19.2 million registered companies (51% of the total). In an empirical assessment of this policy covering the period up to August 2012, Rocha et al. (2018) (see also next section) found that MEI had halved tax costs for the target group and that eligible sectors had experienced an increase by 4.3% in the number of formal firms in the period 2009-2012. However, formalization effects were concentrated in the first implementation period, with the increased rate of formal enterprises that stabilised after 6 months from the introduction of the policy.

In addition to empirical findings from Rocha et al. (2018), the Brazilian small business agency (SEBRAE, 2016) reported how between 50,000 and 70,000 companies graduate every year from MEI into

On the downside, there have been reported cases of abuse of the MEI policy, such as fraudulent declarations (of turnover and business activity to keep eligibility), disguised employment relationships, and the split of one enterprise into more units to avoid exceeding the maximum turnover limit. Furthermore, when the government dropped social security contributions from 11% to 5% of the minimum wage, the policy became more attractive to the target group, but there were also concerns that it could undermine the financial sustainability of the national pension system (ILO, 2019)

On the whole, the experience of MEI suggests that the use of tax reductions simplified regulations mostly favour the formalization of informal enterprises whose business practices are relatively close to those of small formal companies, while they are less successful with “subsistence” entrepreneurs who are less likely to benefit from formalization. Furthermore, the “partial” success of MEI confirms that formalization policies deliver better results when they are implemented as a comprehensive package (awareness raising, regulatory simplification, tax incentives, financial incentives, and enforcement) rather than as individual one-off policies (Jessen and Kluve, 2019).

Source: ILO (2019), Simples Nacional: Monotax Regime for Own-Account Workers, Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Experiences from Brazil, Geneva; Jessen J. and J. Kluve (2019), The effectiveness of interventions to reduce informality in low- and middle income countries, ILO, Geneva; Rocha, R., G. Ulyssea and L. Rachter (2018), “Do lower taxes reduce informality? Evidence from Brazil”, Journal of Development Economics, 134, 28-49; SEBRAE (2016), Cinco anos do Microempreendedor Individual – MEI: um fenômeno de inclusão produtiva, Brasila

Box 4. Mexico's presumptive regime for small taxpayers (

In 2014, the Mexican government introduced a new presumptive fiscal regime (

The main tax advantage of RIF is a 10-year discount on the income tax liability, with the generosity of the rebate that decreases over time, from 100% in the first year of participation in the programme to 10% in the 10th year. Furthermore, the income tax is calculated on a cash-flow basis. RIF participants also benefit from preferential VAT, based on a simplified schedule of tax rates that vary by economic activity, type of product and company turnover. The total VAT liability is reduced based on the same discount rates that apply to the income tax. Social security contributions are also progressively discounted, but at half the rate of the income tax and the VAT.

|

Reduction in tax liability |

Year |

|||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

|

Income tax and VAT |

100% |

90% |

80% |

70% |

60% |

50% |

40% |

30% |

20% |

10% |

|

SSC |

50% |

50% |

40% |

40% |

30% |

30% |

20% |

20% |

10% |

10% |

In terms of compliance rules, RIF taxpayers fill out tax returns every other month, compared to every month in the mainstream tax regime. Moreover, participants can keep their books through an online government tool called “my accounts” (

While a formal impact evaluation of this policy has not yet been realised, also due to its recent introduction, Azuara et al. (2019) show that between 2014 and 2017 more small business owners registered in RIF than in the previous REPECOS regime. RIF has also coincided with an increase in the number of employers paying social security contributions for themselves and their employees. However, while the rate of self-employed not covered in the social security system has dropped from 80.5% to 78%, the rate of uncovered wage workers has remained stable at 45%, which means that the number of formal and informal wage workers have both increased.

Source: Based on Mexico’s SAT (Tax Administration Service) website: https://www.sat.gob.mx/consulta/55158/beneficios-y-facilidades-del-regimen-de-incorporacion-fiscal & Azuara O., R. Azuero, M. Bosch, and J. Torres (2019), “Special tax regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean: compliance, social protection, and resource misallocation”, IDB Working Paper Series, N. 970.

Small business tax rates

Another common form of preferential taxation for MSMEs is the so-called “small business tax rates” (SBTR), which essentially consists in a lower corporate income tax (CIT) rate granted to companies that comply with certain eligibility criteria. De facto, SBTRs only apply to incorporated enterprises. Eligibility requirements mainly refer to the income threshold, but they may also include a capital asset test or an employment test22. Contrary to presumptive regimes the tax base in SBTRs consists of taxable profits, the only difference with the mainstream corporate tax regime being the lower rate at which profits are taxed.

An important distinction in SBTR is whether all taxable income is subject to the preferential rate or only part of it. The first option gives a stronger tax advantage to smaller companies, although it is more fiscally regressive than the second approach, since companies just before and after the income threshold will be subject to very different effective tax rates despite similar levels of income. For this reason, at least in principle, the first approach is also more prone to threshold effects. The advantages and disadvantages of the second approach (i.e. only part of taxable income is subject to preferential taxation) are clearly opposite to those of the first approach: the risk of threshold effects will be lower, but so will the fiscal advantage for smaller companies. Overall, the policy will be less fiscally regressive, applying more similar effective tax rates to companies with similar levels of taxable income.

Other than the proportion of taxable income subject to the SBTR, two other key parameters are the actual rate, notably its difference with the statutory CIT rate, and the income threshold that sets the programme eligibility. Intuitively, the bigger the gap between the SBTR and the mainstream CIT rate, the higher the risk of threshold effects due to a steep increase in the effective tax rate. On the other hand, perhaps counterintuitively, the higher the income threshold, the lower the risk of threshold effects, since fewer companies will face the dilemma of whether to cross the size cut-off and expose themselves to full taxation.

In general, the higher the income threshold, the narrower the difference between the SBTR and the statutory CIT rate, since few percentage points of difference can entail large foregone fiscal revenues when the income threshold is high and concerns many enterprises, some of which will also have relatively high taxable income. On the other hand, when the income threshold is low, there will be more room for a wider gap between the mainstream CIT rate and the SBTR.

Box 5. Small business tax rates in Southeast Asia

The 2018 SME Support Law introduced for the first time the concept of an SBTR for MSMEs in Vietnam. In particular, the law proposed that, instead of the 20% statutory CIT rate, micro-enterprises would be subject to a CIT rate of 15% and small and medium-sized enterprises to a CIT rate of 17%. All taxable income of MSMEs will be subject to the two distinct small business tax rates. The definition of micro, small and medium enterprises follows the national legislation and is based on a combination of revenues, capital assets and employment, which changes along the broad sector categories of industry/construction and trade/services.

In Malaysia SMEs with paid-up capital less than RYM 2.5 million enjoy a 1% reduction on the corporate income tax rate, from 18% to 17%. This same incentive also applies to businesses with RYM 500,000 or less that is taxable annually. New Malaysian SMEs are also exempt for two years from the estimated tax payment.

Source: OECD (2021),

The evidence on the impact of PTRs for MSMEs on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth

Based on a review of the empirical literature, this section of the paper sheds some light on the impact of PTRs for MSMEs on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth. Given the focus on enterprise formalization, this section only takes into consideration the literature on developing and emerging economies, thus excluding studies on high-income economies where informality is less widespread. However, with a view to adding more nuances to the analysis, this section also covers some other size-contingent policies such as certain labour regulations, which de facto act as a payroll tax on business activity and whose impact can therefore be compared to that of other tax policies.

According to the IMF, 25 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and 14 countries in Latin America operated a PTR for MSMEs in 2007 (IMF, 2007), which bears witness to the relevance of this policy in emerging and developing economies. While we do not have more recent statistics on the number of PTRs for MSMEs around the world, it is unlikely that this figure has dropped significantly in the last 10-15 years both because informality is still widespread (Medina and Schneider, 2018) and because these policies can be captured by vested interests once they are established. Given the diffusion of this policy worldwide, it is perhaps surprising that not many of these programmes have been properly assessed, although one possible reason is the lack in developing countries of the extensive firm-level data needed to undertake empirical assessments.

Before moving forward, it is worth noting that there is a small strand of the literature on presumptive regimes that has not looked at their impact on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth, but only at their capacity to collect additional tax revenues from the informal sector. This literature, which mostly draws on cases from Africa, is less relevant for the key research questions of this paper and is briefly summarised in Box 6.

Box 6. The experience of Sub-Saharan Africa with presumptive regimes

Presumptive tax regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa have mostly been used to collect some tax revenues from large domestic informal sectors, but they have not necessarily aimed to formalise the operations of the targeted companies, for example through the means of registration in a business registry. Therefore, also due to lack of firm-level data, the literature on these regimes has not involved empirical analyses to establish impacts on enterprise formalization or enterprise growth, but has rather looked at issues such as success in tax collection.

In 2004, the government introduced a turnover-based presumptive regime for enterprises earning less than TZS 20 million (about USD 20,000 at the time of the reform). Companies without accounting books were asked to pay a lump sum (patent), while companies with books were asked to pay a tax proportional to the turnover plus a lump sum. Four income brackets were established within the TZS 20 million threshold, subject to different rates and lump sums. Semboja (2015) reported an increase in the number of taxpayers registered with this regime from 322,000 in 2008 to 498,000 in 2012, although their relative proportion in the total number of taxpayers decreased from 66% to 42%. While this policy stirred the interest and participation of informal micro-entrepreneurs, it did not generate much additional tax revenues (i.e. less than 1% of the total). Most of these additional revenues came from informal companies keeping basic books, rather than from informal companies without books.

In Zambia, the two main forms of presumptive taxation are a turnover-based tax levied at 3% on individuals and small firms with annual turnover up to ZMW 200 million (USD 50,000) and a withholding tax collected from cross-border traders at 6% of the value of imports exceeding USD 500. These two regimes have reportedly succeeded in increasing tax revenues from the informal sector, from ZMW 5.4 billion (USD 1.35 million) in 2004 to ZMW 90.9 billion (USD 22.7 million) in 2009. As a share of total tax revenues, the informal sector’s contribution rose from 0.3% in 2004 to 1.8% in 2009 (Dube and Casale, 2016).

In some cases, presumptive tax regimes have targeted specific professional categories. In Ghana, for example, the vehicle income tax is a lump-sum tax that applies to informal taxi drivers and that is proportional to the type and size of the vehicle (between USD 3 and USD 60 quarterly). In 2010, the compliance rate was estimated at 85.5%, making this policy quite successful (Dube and Casale, 2016).

Source: Based on Semboja, H. (2015), “Presumptive tax system and its influence on the ways informal entrepreneurs behave In Tanzania”,

Based on these restrictions, we focus our literature review on a relatively small number of empirical papers (11) that specifically look at the impact of PTRs for MSMES on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth, including the eventual existence of threshold effects, in emerging economies. The main findings from each of these papers, all of them investigating presumptive regimes, are summarised in the Annex Table.

This shows clearly that most papers have looked at cases from Latin America, suggesting that it is mostly in this Continent that presumptive regimes have been used to foster enterprise formalization (see also Table 1 for an overview of presumptive regimes in Latin America). However, it is also possible that better data availability has made it possible more quality research in this region than in others where presumptive regimes are also common (e.g. Southeast Asia). In particular, Brazil stands out because it operates two large schemes: Simples Nacional for small companies with annual turnover below BRL 4.8 million and MEI (Individual Micro-entrepreneur) for self-employed people earning less than BRL 81,000 per year. The rest of this section organises evidence under two headings: “presumptive regimes and enterprise formalization” and “presumptive regimes and enterprise growth”.

Table

|

Country |

Name of the regime |

Year of introduction |

Main feature |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina |

Monotributo (Single Tax) |

1998 |

It replaces income tax and VAT and includes health insurance |

|

Bolivia |

Simplified Tax Regime (RTS) |

1997 |

It replaces income tax, VAT and transaction tax |

|

Brazil |

Simples Nacional |

2006 |

It replaces eight taxes (six federal, one state-level and one municipal) through a single document and at a single rate that depends on annual revenues and type of economic activity. |

|

Individual Micro-entrepreneur (MEI) |

2009 |

A fixed monthly payment cover local taxes at the state and municipal levels, while federal income tax is full exempted. |

|

|

Chile |

Simplified Income Tax System |

2007 |

It applies to industry, mining, retail trade and fishing. |

|

Colombia |

Alternative Minimum Income Tax (IMAN) |

2012 |

It replaces income tax |

|

Simplified Alternative Minimum Income Tax (IMAS) |

2012 |

It replaces income tax |

|

|

Ecuador |

Simplified Income Tax Regime (RISE) |

2008 |

It replaces income tax and VAT |

|

Mexico |

Inclusion Tax Regime (RIF) |

2014 |

10-year discount on income tax, VAT and social security contributions |

|

Paraguay |

Corporate Income Tax for Small Taxpayers |

2007 |

It replaces the corporate income tax |

|

Peru |

New Unified Simplified Regime (NRUS) |

2004 |

It replaces income tax and VAT |

|

Special Income Tax Regime (RER) |

2004 |

It replaces income tax |

|

|

Uruguay |

(Single Tax) |

2007 |

It replaces all business-related taxes |

Source: Based on Cetrángolo O. et al. (2018), “Regimenes Tributarios Simplificados”, in J. C. Salazar-Xirinachs & J. Chacaltana (eds

Presumptive regimes and enterprise formalization

With respect to enterprise formalization, the main message from the reviewed cases is that presumptive regimes encourage enterprise formalization, which is generally defined in the literature as the registration and/or tax payment of previously unregistered companies. However, this impact is often short-lived, in the sense that the increased number of enterprise registrations or business tax payments stabilises after a relatively short period of time from the introduction of the policy23. This suggests that presumptive regimes may convince those informal entrepreneurs whose business practices are not too distant from the formal economy to register, but that this incentive alone is not enough to formalize a much larger number of less productive companies24. This is consistent with the point stressed earlier that major advances in formalization are rather the outcome of structural changes in the economy and a broader set of institutional policies that include but go beyond taxation (Chacaltana and Leung, 2020; Infante, 2018).25 In addition, the reviewed presumptive regimes show sustained rates of participation over time, suggesting that self-employed and micro-entrepreneurs appreciate the low tax compliance costs and flexibility of this policy and that, if these regimes were not there, formal business creation would probably be lower. In particular, the experiences of Brazil (two presumptive regimes), Mexico and Argentina all point to sustained use of presumptive regimes over time, while the case of Georgia is a partial exception to this trend.

Turning to some of the specific findings from the literature review, Rocha et al. (2018) find that Brazil’s individual micro-entrepreneur regime (MEI, profiled in Box 3) led to formalization effects in eligible sectors in the range of 4.3%, that is to say, eligible sectors experienced an increase of 4.3% in the number of registered firms, but this only after a programme reform in April 2011 reduced social security contributions from 11% to 5% of the minimum wage26. Only then did MEI become really advantageous for most micro-entrepreneurs (those above the 25th percentile in the earnings distribution), who saw their tax liability halved compared to what they would have had to pay under

Azuara et al. (2019) confirm the positive results of MEI, including in terms of access to social protection. The authors estimate that, between 2009 and 2014, MEI attracted slightly over 1 million informal entrepreneurs into the formal sector in the 12 major urban areas of Brazil. However, this paper also shows that 40% of MEI were no longer enrolled in the regime 4 years after the initial registration. Based on data from the Social Security Institute on year-to-year transitions between social security regimes and the informal sector, the authors conclude that most of this 40% had moved back into the informal sector.

In addition to MEI, Brazil also operates another (larger) presumptive regime, called

Turning to Mexico, the federal government introduced in 2014 a new presumptive regime called

Still in Latin America, Argentina’s

One last case from our literature review comes from Georgia which, in 2010, introduced a turnover-based presumptive regime by which sole proprietors earning less than GEL 30,000 were income-tax exempt (micro-enterprises), while small companies with annual turnover between GEL 30,000-100,000 were taxed at 5% of their annual turnover (3% in case of sufficient documented expenditures). Bruhn and Loeprick (2016), using data from the Georgian Tax Authority, find that 10.8% of Georgian registered companies had opted for the micro-enterprise regime and 23.3% for the small-enterprise regime in 2012. Altogether, the new presumptive regime therefore attracted about 34% of the total stock of formal companies. Based on their empirical models (see Annex Table), the authors also estimate that the presumptive regime led to an increase of 27-41% in the number of newly registered firms below the eligibility threshold of GEL 30,000. However, this increase was limited to the year following the introduction of this policy (2011) – it was not observed in 2012 – and did not concern the other small business tax regime (GEL 30,000-100,000). The authors deduct that this increase was the result of enterprise formalization rather than new enterprise creation, as they assume that the growth in enterprise registrations should have otherwise been more sustained over time35. While two years (2011-2012) are probably too short to draw final conclusions on the impact of this policy on enterprise formalization, findings are broadly in line with those from Brazil (see above), where researchers had also shown that the growth in new enterprise registrations stabilised after the initial post-reform period.

Presumptive regimes and enterprise growth

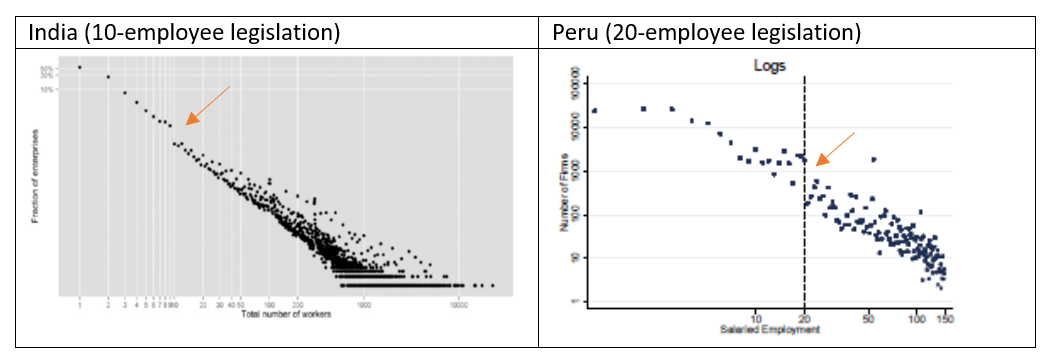

The second question of our literature review is whether presumptive regimes favour small business growth (in terms of turnover, profits or employment) and, linked to this, whether they cause “growth traps” or “threshold effects”, which occur when small business owners intentionally avoid growing beyond the legal threshold of the presumptive regime not to lose its tax advantage. The first main conclusion is that there are frequent examples of enterprise growth within the context of the reviewed presumptive regimes, especially in terms of turnover/profits (rather than employment), but that this growth typically happens within the size limits of the presumptive regime. In other words, few micro and small business owners mature from the presumptive regimes into the national mainstream tax regimes. However, per se, this is not a sign of threshold effects, since business owners may not grow simply because of structural limits to their business model or low managerial skills. In the empirical literature, threshold effects are rather observed when there is a break in the statistical power relation between the two variables of “firm size” (in terms of employment) and “number of companies in each firm size band”, i.e. when there is a gap or a break in the otherwise linear (inverse) relationship between these two variables36. In this respect, based on the limited number of policies observed – 9 in total, some of which analysed by more than one paper – we can tentatively conclude that there is not strong evidence of threshold effects in the case of presumptive regimes, although these effects appear to be slightly more pronounced in the case of senior presumptive regimes (i.e. those with higher turnover thresholds), mostly because of an average larger difference in the effective tax rate between these regimes and the mainstream tax regime. On the other hand, there is stronger evidence of threshold effects in the case of size-contingent labour regulations, although in this case our literature review is really small and only limited to three cases, two from India and one from Peru37. One possible reason is that moving back and forth a turnover size limit is probably less costly than doing the same with an employment size limit, since the latter implies hiring-and-firing administrative costs that do not incur in the first case.

Figure 2. A visualisation of treshold effects in India and Peru (size-contingent labour regulations)

Note: Both graphs are in logarithmic scale and have firm size (employment based) on the horizontal axis and number (or proportion) of companies in the vertical axis.

Source: Amirapu and Getcher (2020) & Dabla Norris et al. (2018)

Turning to some of the details of the reviewed literature, Fajnzylber et al. (2011), in their analysis of Brazil’s

The experience of

Related to the relationship between presumptive regimes and enterprise growth is the link between presumptive regimes and “threshold effects”, which occur when companies intentionally avoid growing not to lose the fiscal advantage of the special tax regime. As noted earlier in the paper, this is one of the most common allegations leveraged at presumptive regimes.

Among the reviewed cases, Hsieh and Olken (2014) look at two examples of preferential tax regimes (Mexico and Indonesia) and one example of size-contingent labour regulations (India, see below). In the case of Mexico, the authors do not observe threshold effects for REPECOS, the preferential regime that preceded RIF until 2014. In other words, there were no signs of a break in the enterprise size distribution at the turnover cut-off of this policy (MXN 2 million), in spite of the strong difference in the effective tax rate before and after the threshold. By the same token, the authors do not find signs of threshold effects in the case of Indonesia’s value-added tax (VAT), which does not apply to companies earning less than IDR 600 million per year. In this case, too, there was no break in the enterprise size distribution around IDR 600 million.

Azuara et al. (2019) look in detail at three examples of size-based legislations from Peru: two presumptive tax regimes and a profit-sharing rule that applies to companies with 20 workers or more40. In the case of the two presumptive regimes, the authors find significant threshold effects for the more senior presumptive regime – RER (Special Income Tax Regime) – which applies to companies earning less than PEN 525,000 per year and employing less than 10 workers. In this case, in fact, the “fiscal cliff” with the mainstream tax regime is particularly steep, since companies exceeding the turnover limit move from being taxed 1.5% of their annual revenues to being taxed 28% of their annual net income. On the other hand, the authors do not find threshold effects for any of the monthly fee segments within the junior presumptive regime (NRUS, New Unified Simplified Regime), nor at the turnover threshold between NRUS and RER. This last point suggests that there are not competition effects between these two presumptive regimes.

Finally, the case of Georgia (Bruhn and Loeprick, 2016) points to mixed threshold effects at the two turnover size limits of GEL 30,000 (micro-enterprise tax regime) and GEL 100,000 (small business tax regime). In 2010, the first year when the new presumptive regime was enforced, there was an increase of companies by the GEL 30,000 turnover cut-off compared to the previous year, from 4,082 to 4,762, which the authors interpret as a sign of underreported revenues. However, the authors do not find signs of underreporting in the following two years, 2011 and 2012. On the other hand, larger and more persistent threshold effects were found for the higher turnover cut-off of GEL 100,000. In this case, the leap between 2009 and 2010 in the number of companies at the turnover threshold was from 7,831 to 12,043 firms, with underreporting persisting in 2011 and then decreasing only slightly in 2012. The authors argue that the stronger threshold effects at the GEL 100,000 limit are the result of a steeper increase in the effective tax rate when business owners move from the small business tax regime into the mainstream tax regime than when they move from the micro-enterprise tax regime into the small business tax regime. This makes the case of Georgia similar to Peru’s, where threshold effects were found for the senior presumptive regime (RER) but not for the junior one (NRUS).

Evidence on threshold effects for size-contingent labour regulations is also mixed. Hsieh and Olken (2014) and Amirapu and Getcher (2020) both look at the case of India, where costly labour regulations kick in at the thresholds of 10 and 100 employees. When Indian companies hire 10 employees (or more), they need to comply with a suite of labour regulations affecting workplace safety, insurance and social security taxes, and severance payment. At 100 or more employees, Indian companies need a government permission to dismiss workers or to shut down operations (i.e. Industrial Disputes Act). Both papers find no major evidence of threshold effects at the cut-off of 100 workers, although the cost of asking a government permission to downsize is probably relevant, if anything in terms of negotiation costs. On the other hand, Amirapu and Getcher (2020) find evidence of threshold effects around the 10-worker cut-off (see also Figure 2), which clearly affects a larger number of companies and may also influence the decision to run a business in the formal or informal economy. The authors estimate that this is due to a steep increase of 35% in the unit labour cost once the size limit is overcome41.

Relevant threshold effects are also found for another size-contingent labour regulation that applies to Peruvian companies that employ more than 20 workers, where employers need to share part of their profits with their workers. Dabla Norris et al. (2018), based on data from both the national economic census and the national tax authority, find evidence of threshold effects (see also Figure 2). Moreover, they also find that the use of non-salaried workers increase rapidly as companies approach the size of 20 salaried workers, which the authors take as a sign of recourse to informal or semi-formal labour (e.g. consultants and service provision contracts) among companies around the 20-employee limit. In this respect, the authors also find threshold effects with respect to “sales per worker” and “profits per worker”, with the value of both variables dropping at the 20-employee cut-off. This may suggest underreporting of sales and profits – to avoid sharing a bigger slice of profits with workers – but also lower average productivity due to the contracting of a larger proportion of non-salaried workers42. Concerning this profit-sharing rule in Peru, Azuara et al. (2019) find identical results to Dabla Norris et al. (2018). Figure 3 summarises the results of the literature review on the specific issue of threshold effects.

Figure 3. Overview of treshold effects by policy based on the literature review

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Mexico's REPECOS |

• |

|

|

Indonesia’s VAT |

• |

|

|

Peru's junior presumptive regime (NRUS) |

• |

|

|

Peru's senior presumptive regime (RER) |

• |

|

|

Georgia's micro tax regime |

• |

|

|

Georgia's small tax regime |

• |

|

|

|

||

|

India's 100-employee legislation |

• |

|

|

India's 10-employee legislation |

• |

|

|

Peru's 20-employee legislation |

• |

Source: Elaboration of the Author

Main policy messages on PTRs for MSMEs

This section draws some main policy takeaways on PTRs for MSMEs, building on the evidence presented in the previous sections. Ministries of Finance and National Tax Authorities are the government entities mostly responsible for the design and implementation of tax policies, although social dialogue with social partners can help come up with policies that address the needs of both employers and workers.

General policy messages on enterprise formalization

• Widespread formalization is the long-term outcome of both the structural transformation of the economy and the implementation of a wide range of institutional policies. As such, preferential taxation can play a role in encouraging formalization, but only if it is part of a broader set of policies aimed at improving the overall business environment, productivity growth at the sector (e.g. value chain development) and firm levels (business development services and training), regulatory simplification, financial incentives, and improved rule enforcement. Cultural aspects (e.g. the diffusion and acceptance of corruption) also matter, although these aspects can also improve through the process of economic growth and poverty reduction.

• It follows that PTRs for MSMEs are much better at formalizing those informal (unregistered) companies whose business practices are relatively close to those of the formal sector, while they are unlikely to succeed with the many “subsistence” enterprises whose productivity levels are only a small fraction of the average productivity in the formal economy and which do not benefit very much from formalization.

• Support in access to finance and business development services, when combined with preferential taxation, can further enhance the attractiveness of the formal sector. Digital technologies can also support formalization efforts. The term “e-formality policies” has been coined to indicate those instruments – online business registration, online registration of workers and digitised commercial transactions – which can help advance the enterprise formalization agenda.

Operational aspects of PTRs for MSMEs

• The two main types of PTRs for MSMEs in the context of emerging economies are presumptive regimes, mostly aimed at self-employed people and micro-enterprises that are not incorporated, and “small business tax rates” which apply to small corporate businesses.

• Presumptive regimes are called this way because they “presume” taxable income based on another easier-to-calculate variable, such as turnover, employment, capital assets, electricity consumption or the floor space of the business. It follows that the choice of the “proxy variable” is important (see Box 1 for details).

• Presumptive regimes come as a package that may include different components, including a lower tax rate, a simplified method of income tax calculation, access to social protection, simpler tax compliance requirements and additional tax exemptions (e.g. on VAT). The more fiscally attractive the package, compared to the mainstream tax regime, the more successful the policy will likely be in terms of participation. However, the more generous the presumptive regime, the greater its adverse impact on tax equity and, potentially, on foregone fiscal revenues.

• Presumptive regimes based on the payment of a lump sum are easy to implement and attractive for micro-enterprise owners. However, they are also fiscally regressive and anticyclical by nature, calling for some caution in their implementation. In particular, eligibility conditions should be easy to verify, possibly through digitised tax systems, business owners should be required to keep some books, and the lump sum should be adjusted according to the economic cycle.

• Other tier-based presumptive regimes in which the tax duty is calculated as a fixed rate of turnover and where the tax rate changes by sector and enterprise size are less fiscally regressive but also more complex to manage for national tax authorities.

• Small business tax rates (SBTRs) are another common form of preferential taxation for MSMEs that consist in a lower corporate income tax (CIT) rate. The three main parameters of this policy are the income threshold that sets the programme eligibility requirements, the rate of the SBTR (and its difference with the statutory CIT rate), and whether all taxable income is subject to the preferential rate or only part of it. The appropriate decision on these parameters depends on national conditions. As a rule of thumb, the higher the income threshold, the narrower should be the difference between the SBTR and the statutory CIT rate, since the programme will apply to a larger number of companies and a larger share of national income, making it more expensive for the government. Conversely, if the income threshold is lower, the policy will apply to fewer companies and a lower share of national income, leaving some room for a wider gap between the SBTR and the statutory CIT rate.

What to expect from presumptive regimes for MSMEs

• Evidence from our small literature review on emerging economies (11 papers looking at 13 different policies overall) suggests that the reviewed presumptive regimes have mostly helped the formalization of micro and small enterprises whose business practices were not too distant from those in the formal economy. In this literature, enterprise formalization was defined as enterprise registration and/or tax registration and annual tax payments.

• The reviewed presumptive regimes also showed a growing rate of participation over time, which can be taken as a sign that the self-employed and micro-entrepreneurs appreciate the flexibility offered by this policy. On the downside, the experience of this policy points out that governments should not expect major tax revenues from presumptive regimes.

• While the literature does not establish a causal relationship, there are frequent examples of enterprise growth within the context of the reviewed presumptive regimes, especially in terms of turnover/profits (rather than employment). However, this growth typically happens within the size limits of the presumptive regime, that is, few enterprises mature from presumptive regimes into a more senior tax regime.

• As to threshold effects (i.e. enterprises that intentionally avoid growing not to lose the tax advantage), evidence among the reviewed cases is mixed. There is very little sign of such effects in the case of junior presumptive regimes aimed at self-employed and micro-entrepreneurs, while these effects appear to be more pronounced in the case of senior presumptive regimes (due to a greater difference in the effective tax rate compared to the mainstream tax regime) and size-contingent labour regulations (due to the high administrative costs of hiring and firing workers).

Conclusion

This paper has drawn on a literature review to examine the relationship between PTRs for MSMEs and enterprise formalization and enterprises growth, including whether this policy causes threshold effects. After a brief introduction on the distinction between the income taxation of unincorporated and incorporated enterprises, the paper has presented the pros and cons of this policy from a conceptual perspective and the two main types of PTRs for MSMEs in the context of emerging economies: presumptive regimes and small business tax rates (SBTR).

The second part of the paper has looked at the evidence on the impact of presumptive regimes on enterprise formalization and enterprise growth. In a nutshell, the reviewed literature suggests that presumptive regimes encourage enterprise formalization, but only for informal companies whose business practices are not too different from those prevailing in the formal economy. On the other hand, the impact of this policy on the formalization of very low-productivity “subsistence” business owners is virtually nil. Evidence on threshold effects is mixed. There is no sign of such effects in the case of the reviewed junior presumptive regimes; these effects appear to be slightly more pronounced in the case of senior presumptive regimes; and they appear to be more significant in the case of size-contingent labour regulations (although, in this case, the literature review only covered three policies).

Finally, the last section has drawn some general policy messages for policy makers interested in introducing or reforming PTRs for MSMEs in their countries, keeping in mind that taxation, including PTRs for MSMEs, is just one of the institutional policies that need to be in place to make major strides in the formalization of the economy.

The main limitation of this paper clearly consists in its nature of review of the existing literature. Going forward, two important areas for further research would be the following. First, it is perhaps surprising that, despite the diffusion of PTRs for MSMEs, not many of these programmes have been formally evaluated, including in large upper-middle income economies. Presumptive regimes are widely used across the developing world and there is clearly a need to know more about their effects on business formalisation and business growth, but also on other issues such as access to social protection and poverty reduction. Second, PTRs for MSMEs are also common in high-income economies, such as Canada, Japan or Italy. In this respect, it would be interesting to compare the performance of this policy between high-income and middle-income economies to see if different patterns emerge, for example in terms of impacts on enterprise growth, across different stages of economic development43.

Annex Table: Main findings from the empirical literature on presumptive regimes, enterprise formalization and enterprise growth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hsieh C. T. and B. Olken (2014), The Missing “Missing Middle”,

|

Mexico (UMI) Indonesia (UMI) India (LMI) |

Mexico: Companies with annual turnover below MXN 2 million are subject to a flat tax of 2% of their sales and exempt from VAT, payroll tax and other business income taxes (REPECOS regime, later replaced by RIF). Indonesia: companies whose annual revenues are below IDR 600 million are VAT exempt. India: Industrial Disputes Act (IDA) imposing stricter employment regulations (i.e. firing and closing permission from the government) to companies with 100+ workers. |

Descriptive micro-firm analysis using administrative data. |

No threshold effects in the case of Mexico (presumptive regime) and Indonesia (VAT exemption). Limited threshold effects in the case of India (employment regulations), corresponding to 0.2% of all Indian formal firms. |

|

Rocha, R., G. Ulyssea and L. Rachter (2018), “Do lower taxes reduce informality? Evidence from Brazil”,

|

Brazil (UMI) |

MEI regime (Individual Micro-entrepreneur) applies to micro-entrepreneurs employing no more than one person and with annual revenues below BRL 81,000. Some of the preferential conditions are as follows: i) a monthly fixed payment to cover state and municipal taxes; ii) exemption from federal income taxation; iii) social security contributions set at 5% of the minimum wage; iv) taxes paid electronically once a year. |

Difference-in-differences regression at the industry-by-region level (aggregate) and individual level (to estimate transition in employment status) |

MEI was introduced in 2009 but only generated a real tax saving for the target group when social contributions were dropped from 11% to 5% of the minimum wage in April 2011. In the period April 2011-August 2012, MEI led to an increase of 4.3% in the proportion of formal firms in the sectors eligible for the programme. This increase came from real enterprise formalization, rather than from new enterprise creation or greater survival of existing firms. Formalization effects peaked after 6 months from the policy reform. On the downside, even after the 2011 reform, MEI did not show any significant effects on the total shares of formal/informal workers, the unemployment rate and the overall proportion of entrepreneurs. The observation period of this study was 16 months. |

|

Fajnzylber P., W. Maloney and G. Montes-Rojas (2011),

|

Brazil (UMI) |

|

Regression discontinuity approach and Difference-in-difference approach to estimate the impact of |

This paper finds that |

|

Monteiro, J. and Assunção, J. (2012), “Coming out of the Shadows? Estimating the impact of bureaucracy simplification tax cut on formality in Brazilian microenterprises”,

|

Brazil (UMI) |

|

Difference-in-differences methodology. |

|

|

Amirapu A. and M. Getcher (2020), “Labour regulations and the cost of corruption: Evidence from the Indian firm size distribution”,

|

India (LMI) |

A suite of labour regulations (workplace safety, insurance and social security taxes, and severance payment) only apply to companies employing 10+ employees. Industrial Disputes Act (i.e. firing and closing permission from the government) applies to companies with 100+ workers. |

Theoretical model and empirical strategy to test the model |

No threshold effects for the 100+ worker legislation (i.e. Industrial Dispute Act). Significant threshold effects at the 10+ worker threshold due to increase by 35% |

|

Dabla-Norris et al. (2018), “Size-dependant policies, informality and misallocation”, IMF Working Paper, WP/18/179

|

Peru (UMI) |

Profit-sharing rule (with workers) for companies employing 20 workers or more. |

Empirical analysis. Extra regulations modelled as a yearly payroll tax. |

There is evidence of threshold effects at the 20-employees threshold. Wages decline by 0.4-1% and profits by 3-4% when regulation is introduced in the empirical model. The impact on output would be worse if the threshold were lowered (i.e. the regulation would apply to more firms). |

|

Piza C. (2018), “Out of the Shadows? Revisiting the impact of the Brazilian SIMPLES Program on Firms’ Formalization rate”,

|

Brazil (UMI) |

|

Regression-discontinuity and difference-in-differences methodology. |

|

|

Azuara O., R. Azuero, M. Bosch, and J. Torres (2019), “Special tax regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean: compliance, social protection, and resource misallocation”, IDB Working Paper Series, N. 970.

|

Peru (UMI) Brazil (UMI)

|

Peru: i) The NRUS tax regime allows sole proprietors with annual revenues below PEN 360,000 to pay a lump sum covering income tax and VAT; ii) the RER tax regime applies to businesses with annual revenues below PEN 525,000 and with less than 10 employees: tax rate is 1.5% of revenues instead of 28% of net income; iii) profit-sharing rule (with workers) for companies employing 20 workers or more. Mexico: The RIF regime targets mostly retail trade and services not involving the employment of regulated professions and earning annual revenues below MXN 2 million. It offers a 10-year regressive discount on the business income tax rate (100% on year 1, 90% on year 2, etc.); SSC for employees (50% on year 1 and 2, 40% on year 3 and 4, etc.); and VAT rates (same discount as per the income tax rate). Brazil: |

Descriptive micro-firm analysis using administrative data. |

Threshold effects are found for the more senior RER regime and for the “profit-sharing” rule. Threshold effects are not found for the more junior presumptive regime (NRUS) and at the turnover limit between the NRUS and RER (i.e. no competition effects between the two regimes).

MEI: Between 2009 and 2014, about 1 million people enrolled in MEI, many of whom were previously not enrolled in the social security system. However, 40% of MEI were no longer enrolled in the regime 4 years after the initial registration, with signs that they had moved back into the informal sector. Lack of competition effects between MEI and

In Mexico, between 2014 and 2017, more small business owners registered in the new RIF regime than in the previous REPECOS regime. RIF has coincided with an increase in the number of employers paying social security contributions for themselves and for their employees. However, while the rate of self-employed not covered in the social security system has dropped from 80.5% to 78%, the rate of uncovered wage workers has remained stable at 45%. |

|

Bruhn, M. and J. Loeprick (2016), “Small business tax policy and informality: evidence from Georgia”,

|

Georgia (UMI) |

Based on a 2010 national tax reform, sole proprietors with annual turnover below GEL 30,000 were exempt from income taxation (micro-enterprises). Businesses with annual turnover between GEL 30,000 and GEL 100,000 (small enterprises) were taxed at 5% of annual turnover (3% in case of sufficient documented expenditures). Micro-enterprises were also exempt from VAT payment. |

Regression discontinuity design around the two thresholds (GEL 30,000 and 100,000) to estimate the effects of the presumptive regime on enterprise formalization, enterprise creation and “threshold effects”. |

The paper finds that the new presumptive regime introduced in 2010 led to an increase of 27-41% (depending on the estimation model) in the number of newly registered enterprises within the annual turnover threshold of GEL 30,000 (micro-enterprise tax regime) in 2011. This increase in enterprise registration did not happen again in 2012, leading the authors to believe it was mostly the result of enterprise formalization. No increase in enterprise registrations was observed for the small business tax regime (GEL 30,000-100,000). The paper finds threshold effects especially at the turnover cut-off of GEL 100,000 due to a steeper increase in the effective tax rate when moving from the small business tax regime into the general tax regime. |

|

Cetrángolo O., A. Goldschmit J.C. Gómez Sabaíni and D. Morán (2013), & Cetrángolo O., J. C. Gómez Sabaini, A. Goldschmit and D- Morán (2018), “Regimenes Tributarios Simplificados”, in J. C. Salazar-Xirinachs & J. Chacaltana (eds.),

|

Argentina (UMI) |

Argentina’s |

Descriptive statistical analysis |

The papers show that the number of small business owners enrolled in this policy increased by five times between 1998 and 2018, from 640,000 to 3.45 million. One of the papers (2013) also finds that, on an annual basis, 80% of change in income brackets within Finally, 80-90% of micro-entrepreneurs enrolled in the programme were up-to-date with tax payments, depending on the year. However, tax revenue from this policy did not exceed 0.36% of GDP at any given year. |

Note: The literature is ordered based on number of citations per year, where this is calculated from the year following publication up to 2020. UMI stands for Upper-Middle Income and LMI for Lower-Middle Income. For Mexico, REPECOS is

References

-

Amin M., Ohnsorge F., Okou C., 2019, “Casting a shadow: Productivity of formal firms and informality”, Policy Research Working Paper, N. 8945, World Bank, Washington DC.

-

Amirapu A. and Getcher M., 2020, “Labour regulations and the cost of corruption: Evidence from the Indian firm size distribution”,

The Review of Economics and Statistics , 102(1), 34-48. -

Azuara O., Azuero R., Bosch M., Torres J., 2019, “Special tax regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean: Compliance, social protection, and resource misallocation”, IDB Working Paper Series, N. 970.

-

Beck T., Demirgüç-Kunt A., Maksimovic V., 2008, “Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different?”,

Journal of Financial Economics , 89(3), 467–87. -

Bird R. and Zolt E., 2010, “Dual Income Taxation and Developing Countries”,

Columbia Journal of Tax Law , Vol. 1, 174-217. -

Braunerhjelm P., Eklund J.E., Thulin, P, 2019, “Taxes, the tax administrative burden and the entrepreneurial life cycle”,

Small Business Economics , 56, 681–694. -

Bruhn M. and Loeprick J., 2016, “Small business tax policy and informality: evidence from Georgia”,

International Tax and Public Finance , 23, 834–853. -

Cetrángolo O., A. Goldschmit, J.C. Gómez Sabaíni and D. Morán (2013), “Desempeño del Monotributo en la formalización del empleo y la ampliación de la protección social”, Working Document N. 4, ILO Country Office of Argentina.

-

Cetrángolo O., Gómez Sabaini J.C., Goldschmit A. and Morán D., 2018, “Regimenes tributarios simplificados”, in Salazar-Xirinachs J. C. & Chacaltana J. (eds.),

Políticas de Formalización en América Latina: Avances y Desafíos , ILO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. -

Chacaltana J. and Leung V., 2020, “Pathways to formality: Comparing policy approaches in Africa, Asia and Latin America”, in ILO,

Global Employment Policy Review 2020: Employment policies for inclusive structural transformation , International Labour Office, Geneva. -

Chacaltana J., Leung V. and Lee M., 2018, “New technologies and the transition to formality: The trend towards e–formality”, Employment Working Paper, No. 247, ILO, Geneva.

-

Chen D. and Mintz J., 2011, “Small Business Taxation: Revamping Incentives to Encourage Growth”, SPP Research Papers, Vol. 4, No. 7, University of Calgary.

-

Coolidge J. and Yilmaz F., 2016, “Small Business Tax Regimes”, Viewpoint No. 349, World Bank, Washington.

-

Dabla-Norris et al. (2018), “Size-dependant policies, informality and misallocation”, IMF Working Paper, WP/18/179, Washington DC.

-

Djankov S., Ganser T., McLiesh C., Ramalho R. And Shleifer A., 2010, "The effect of corporate taxes on investment and entrepreneurship,"

American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, American Economic Association , vol. 2(3), 31-64. -