Social policy advice to countries from the International Monetary Fund during the COVID-19 crisis: Continuity and change

Abstract

This paper explores whether there has been a change in International Monetary Fund (IMF) policy advice and conditions in its loan programmes and Article IV surveillance by examining the 148 country reports for IMF programmes in 2020, in the context of significant shifts in its global macroeconomic policy framework during the COVID-19 pandemic. It documents the policy recommendations made in these reports and finds that the IMF has supported increased expenditure on health care and cash transfer programmes, often on a temporary basis, even when it meant higher fiscal deficit and public debt. However, it also finds that the IMF has supported fiscal consolidation and reduction of public debt even more frequently, in 129 of the 148 reports examined. This seems to corroborate the findings of a number of recent studies. Given the pronounced gaps in social protection coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy across all countries, it is essential that the measures taken to cope with the emergency do not remain a mere stopgap response, but progressively lead to the establishment or strengthening of rights-based national social protection systems, including floors. To do so, countries can and should pursue diverse financing options that are equitable in order to mobilize the financial resources needed for social investments, including investments in social protection systems and quality public services.

JEL Classification: I3, H6, H53, H55.

Keywords: social protection, social security systems, social protection floors, child allowances, maternity benefits, disability benefits, social pensions, social health protection, social security contributions, public expenditure, fiscal space, domestic resource mobilization, official development assistance (ODA), developing countries, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused massive disruptions to the global economy and forced policymakers to respond to the newly created challenges. Many policy institutions have therefore had to rethink their established approaches and their usual policy responses. Governments, mostly in high-income countries, for example, have instituted large-scale stimulus packages, including a range of income-support measures, while central banks have revised or are considering revising their monetary policy framework.

In many countries, firms have been receiving wage subsidies from their respective governments to facilitate the retention of workers, and governments are procuring essential health-care equipment to scale up health-care capacity. However, many low- and middle-income countries have struggled to mount a proportionate stimulus response to contain the adverse impacts of the pandemic in the way that high-income countries have been able to do, reflecting a considerable “stimulus gap” (ILO 2020a).

In this context, the IMF acted swiftly to provide substantial support for developing countries in the form of short-term loans and relief from servicing the debt owed to the IMF. This came in tandem with encouraging statements from the Managing Director, underlining that “supportive fiscal and monetary policies will need to continue until we can secure a safe and durable exit from the crisis. Premature withdrawal of this support could derail the recovery and incur larger costs”.1 In 2020, the IMF made 113 disbursements totalling $93.7 billion to 83 countries, including 3 high-income countries, 22 upper-middle-income countries, 31 lower-middle-income countries and 27 low-income countries.

Yet, previous research has shown that IMF loans are often accompanied by policy advice and programme targets that encourage or require fiscal austerity (see, for example, Kentikelenis et al. 2016; Rickard and Caraway 2019; Stubbs et al. 2017; and Thomsom et al. 2017). It has also shown that IMF recommendations for fiscal consolidation often entail a reduction in the size of the public sector and public social expenditure. This has often meant a reduction in public expenditure on social protection schemes and the targeting of “safety nets”, entailing reform of pension systems and health care. It has also entailed cuts in operational expenditures, such as the public sector wage bill, which tends to adversely impact the delivery of essential public services. It has also meant the deregulation of labour markets beyond the public sector. To the extent that this leads to the informalization of employment, it could have an effect on fiscal balances by reducing social security contributions and possibly taxes, while potentially increasing public expenditure on social assistance. Further, similar policy advice has been provided to countries that were not receiving loans, under the Article IV surveillance function of the IMF (Ortiz and Cummins 2011 and 2019; Ortiz et al. 2015; Stubbs et al. 2017).

In this paper, we explore whether there has been a change in IMF policy advice and conditions in its loan programmes and Article IV surveillance by examining the 148 country reports for IMF programmes in 2020, in the context of significant shifts in its global macroeconomic policy framework during the pandemic.2 We document the policy recommendations made in these reports and find that the IMF has supported increased expenditure on health care and cash transfer programmes, often on a temporary basis, even when it meant higher fiscal deficit and public debt, a perspective that is also reflected in the IMF’s

However, we also find that the IMF has supported fiscal consolidation and reduction of public debt even more frequently, in 129 of the 148 reports examined. The latest issue of the IMF’s

Our analysis shows that the IMF recommended many measures, including the reduction of energy and food subsidies in the medium term; pension reform; increased targeting of subsidies and social programmes; cuts to the public sector wage bill; and increased fees for public services. On the revenue side, the IMF recommended raising tax revenues from indirect taxes, such as through a value added tax, which tends to be regressive, far more frequently than more progressive direct taxes, such as income, profit and property taxes. Hence, despite some change in IMF policy advice, especially with regard to public expenditure on health care and targeted safety nets, which aligns with the statements of its leadership, we also discern considerable continuity with past approaches.

This review was undertaken because of the critical implications of IMF policy advice on social spending for universal social protection policies and systems. Indeed, given the complementary mandates and expertise of the ILO and the IMF, there is a strong basis for an ILO–IMF engagement. How can countries build national social protection systems, including floors, without the necessary fiscal space? Conversely, how can countries achieve macroeconomic stability and structural transformation of the economy if they do not have a robust social protection system that prevents poverty, contains inequality, builds human capabilities and productivity, and creates a sense of social cohesion, solidarity and fairness that is so critical for social and political peace?

In other words, just as social protection policies need enabling fiscal and macroeconomic policies, so too macroeconomic performance is contingent on adequate investments in social protection systems that can support people’s life and work transitions and facilitate structural transformations of the economy.

Recognition of this two-way relationship was part of the impetus for the 2019 IMF Strategy for Engagement on Social Spending (IMF 2019). On the part of the ILO, there is considerable interest in IMF macroeconomic policy advice, especially when ascertaining whether social spending floors are set at a sufficiently high level to enable countries to build universal social protection systems, including social protection floors, in order to protect people’s incomes and health, both during and beyond this crisis. Such advice is also relevant to ascertaining whether countries are encouraged to use this benchmark as a floor rather than a ceiling.

Methodology

To analyse the extent of changes in IMF policy advice, country reports that accompanied the loans made by the IMF and Article IV consultations conducted by the IMF were examined. A full list of the IMF reports reviewed in this study is provided in Appendix 2. The analysis followed the methodology used in the ILO paper entitled “The Decade of Adjustment: A Review of Austerity Trends 2010–2020 in 187 Countries” (Ortiz et al. 2015) and identified the recurrent policy recommendations made in 148 publicly available reports for programmes or Article IV consultations between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020. In this period, many different instruments were used to make loans to governments, including two new facilities: the Rapid Credit Facility and the Rapid Financing Instrument (see Appendix 1).

The reports that accompanied the arrangements listed in Appendix 1 (a) to (g) and any Article IV consultation reports completed in 2020 were analysed. Based on a smaller sample of reports from each region and instrument type, the recurrent policy recommendations or programme targets in these reports were identified and then all the reports in the sample of 148 were examined for these policy recommendations or programme targets. The recurrent policy advice or programme targets identified in this way are shown in table 1. Whenever policy advice or programme targets related to these keywords were found, they were marked in the country report/policy advice matrix along with a note on the purpose of these reforms. Section III discusses the key policy recommendations or conditions of IMF programmes in 2020.3

Table 1: Recurrent policy advice/programme targets tracked in IMF reports

|

Fiscal Consolidation |

Reduction of Public Debt |

Health Reform |

|

Social Spending Floor |

Non-Priority Spending |

Cash Transfers |

|

Subsidy Reform |

Pension Reform |

Social Security Contributions |

|

Wage Bill Cut/Freeze |

Labour Flexibilization Reform |

Fees for Public Services |

|

Public Private Partnerships |

Privatization |

Value Added Tax |

|

Corporate Income Tax |

Personal Income Tax |

Wealth/Property Tax |

Source : Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

IMF lending activity in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and reports reviewed

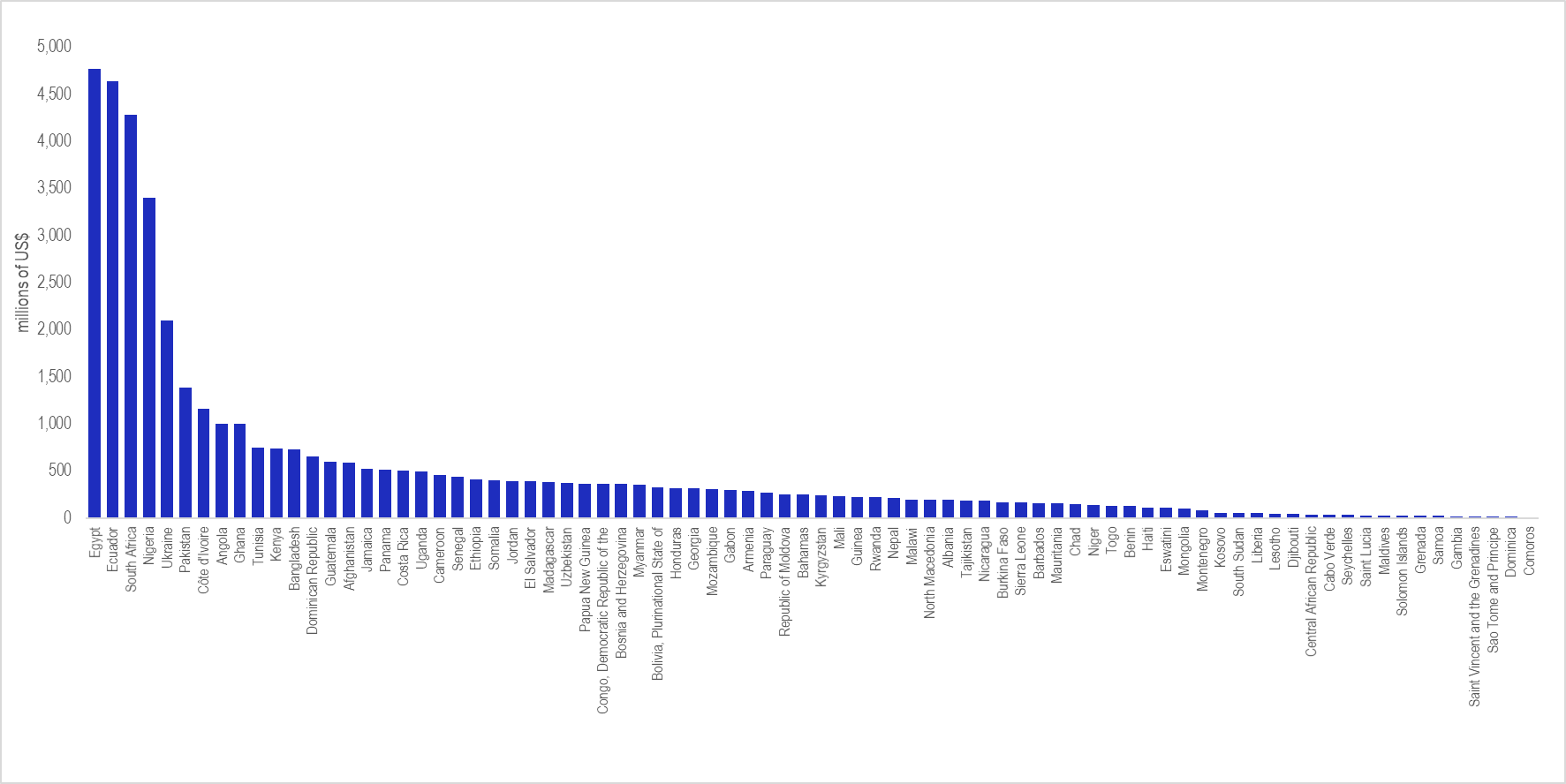

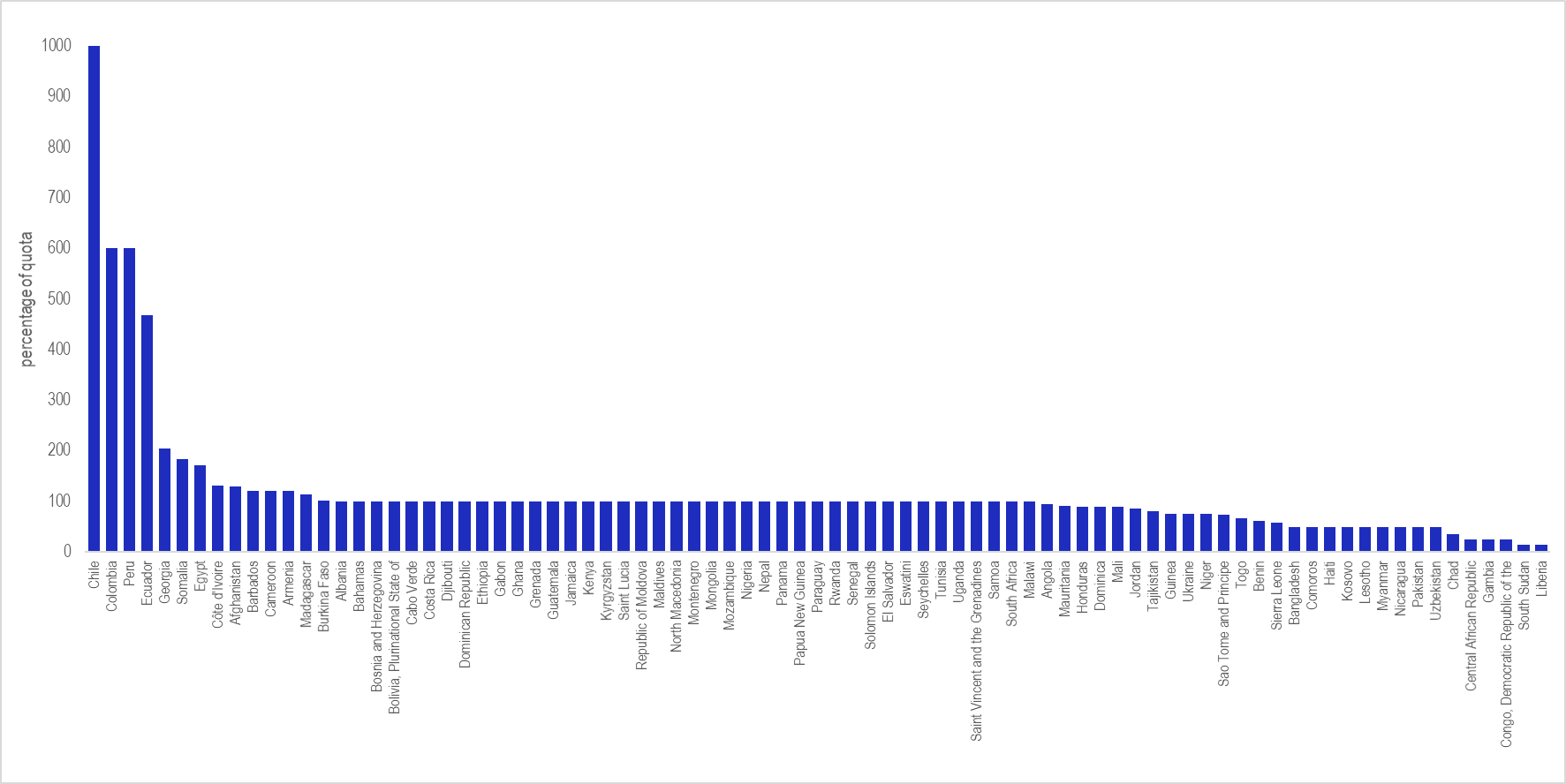

In 2020, the IMF made 113 disbursements totalling $93.7 billion to 83 countries. This section provides a summary of the lending activity undertaken by the IMF in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Figures 1 and 2 show the size of IMF loan disbursements across countries, in terms of total value and the percentage of a country’s quota that they represent, respectively. The size of the disbursements ranged from the $12 million extended to the Comoros to the $23,900 million extended to Chile. The percentage of the IMF quota that these disbursements constituted ranged from 14 per cent (Liberia) to 1,000 per cent (Chile).

Figure 1: Loan disbursement in 2020, in millions of US$

Note: Graph excludes loans extended through the Flexible Credit Line to Chile, Peru, and Colombia

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Figure 2: Loan disbursement in 2020, percentage of quota

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

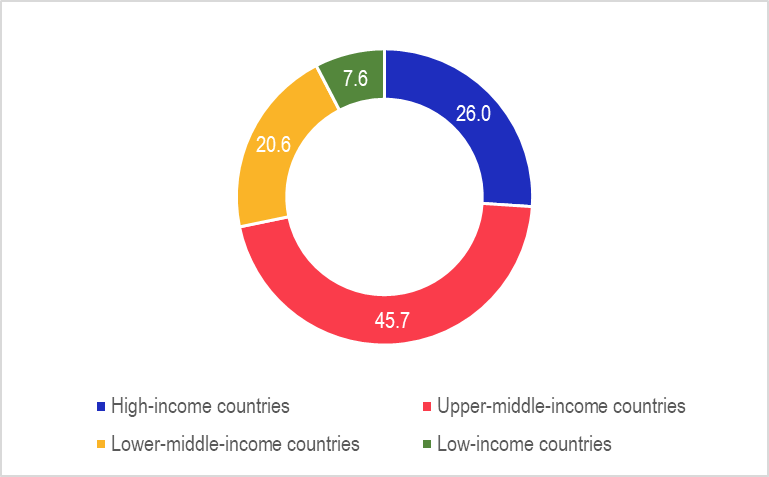

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the amount lent by the IMF across country income groups. We can see that the loans to upper-middle-income countries constituted the largest share of loans extended by the IMF, while loans to low-income countries constituted the smallest share of IMF loan disbursements in 2020.

Figure 3: Distribution of loan disbursements by country income group in 2020, in percentage

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

On a per capita basis,4 the IMF disbursements during 2020 analysed in this paper corresponded to US$1,232.52 per person in 3 high-income countries (Chile, Bahamas and Barbados); US$132.58 in 21 upper-middle-income countries; US$23.54 per person in 31 lower-middle-income countries; and US$8.35 per person in 27 low-income countries.

Table 2 shows the most frequently used instruments by the IMF to extend loans to governments during the COVID-19 pandemic by region. It should be noted that some country programmes included disbursements under multiple instruments. Hence, Table 2 reflects the use of the instruments rather than the total number of country reports. It can be seen that the Rapid Credit Facility was used most frequently to make loans, followed by the Rapid Financing Instrument (see below). The Rapid Credit Facility was used most frequently to provide support to governments in East Asia and the Pacific, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, while the Rapid Financing Instrument was used most frequently to provide support to governments in Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Middle East and North Africa.

Table 2: IMF report or instrument type, by region, 2020

|

|

East Asia and Pacific |

Europe and Central Asia |

Latin America and the Caribbean |

Middle East and North Africa |

North America |

South Asia |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Article IV |

7 |

9 |

9 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

36 |

|

Flexible Credit Line |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Extended Credit Facility |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

20 |

|

Stand-By |

0 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Rapid Credit |

4 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

30 |

49 |

|

Rapid |

3 |

9 |

11 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

11 |

39 |

|

Extended |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

12 |

|

Other |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

|

Total |

14 |

31 |

35 |

7 |

1 |

7 |

76 |

171 |

Source : Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Table 3 shows the most frequently used instruments by the IMF to extend loans to governments during the COVID-19 pandemic by income group. As in Table 2, it is important to note that some country programmes included disbursements under multiple instruments and therefore Table 3 reflects the use of the instruments rather than the total number of country reports. The Extended Fund Facility, which requires a comprehensive programme over the medium- to long-term with commitments, was used to provide support to all groups of countries, while the Rapid Financing Instrument, which is directed to countries experiencing disasters, emergencies or commodity price shocks and does not require a full economic programme, was used most frequently to provide support to upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income countries. On the other hand, the Rapid Credit Facility, which is mostly directed towards low-income countries, does not require a full economic programme and has a ceiling for the amount it disburses, was used most frequently to provide support to lower-middle-income and low-income countries.5

Table 3: IMF report or instrument type, by country income group, 2020

|

|

High-income |

Upper-middle-income |

Lower-middle-income |

Low-income |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Article IV |

11 |

12 |

6 |

7 |

36 |

|

Flexible Credit Line |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Extended Credit Facility |

0 |

0 |

6 |

14 |

20 |

|

Stand-By Arrangement |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

Rapid Credit Facility |

0 |

4 |

19 |

26 |

49 |

|

Rapid Financing Instrument |

1 |

15 |

19 |

4 |

39 |

|

Extended Fund Facility |

2 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

12 |

|

Other Facility |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

|

Total |

15 |

39 |

61 |

56 |

171 |

Source : Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Key policy recommendations/conditions of IMF programmes and surveillance in 2020

As outlined in section III, the IMF was very active in 2020 and made several loan disbursements in addition to its previously scheduled loan agreements and Article IV consultations. Therefore, in the 148 reports analysed, many different recommendations made by IMF staff and many different indicative or performance targets set for national governments were identified. They can be divided into four main categories:

-

recommendations made or conditions set regarding fiscal deficit and public debt;

-

recommendations made or conditions set regarding government expenditure on social policies;

-

recommendations made or conditions set regarding social insurance, including with regard to social security contributions and pension reforms; and

-

recommendations made or conditions set regarding government revenue.

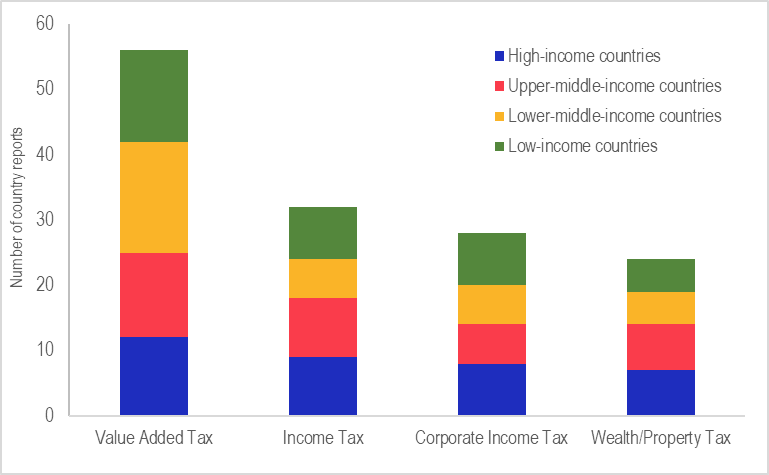

Categories (b) and (d) are broken down further. Under category (b), the recommendations made regarding government expenditure cover a diverse range of policy issues, including most notably health expenditure, cash transfers, reduction of non-priority expenditures, reduction of subsidies, public sector wage bill cuts/freezes, and fees for public services. Under category (d), information in IMF country reports regarding value added taxes, personal income taxes, corporate income taxes and wealth or property taxes is presented.

New austerity in the context of fiscal deficit and public debt

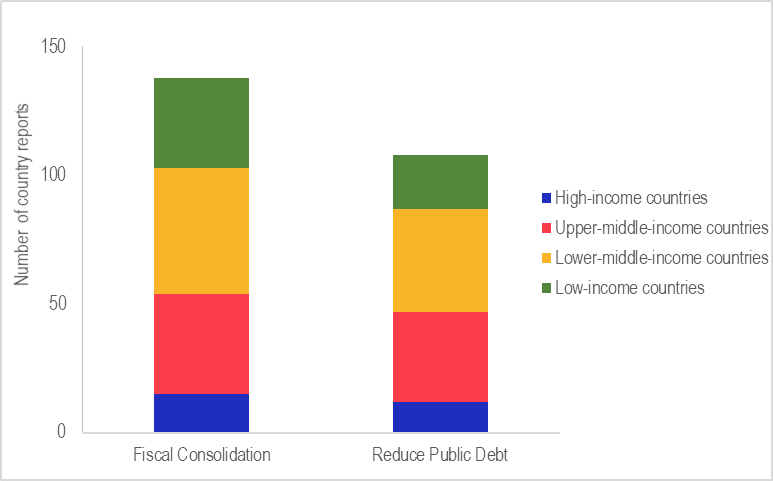

While IMF documents recommended increased expenditure on health care and expansion of the “social safety nets” (see section V), the most recurrent policy recommendation was to begin or resume fiscal consolidation as soon as the conditions created by the health and economic crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic alleviate. In a subset of reports, this recommendation was made in order to put public debt on a downwards trajectory. Figure 4 shows the number of country reports in which these recommendations were made, disaggregated by country income groups. It can be seen that the recommendation to proceed with fiscal consolidation and reduce public debt was made in 138 and 108 of 148 country reports, respectively. For example, in the Article IV consultation for Brazil (report 20/311), in the chapter entitled “Staff appraisal”, the recommendation is as follows:

In most cases, IMF staff recommended that governments begin efforts to reduce fiscal deficit in 2021. Munevar (2020) also finds that 72 countries are projected to begin the process of fiscal consolidation in 2021 and reduce the fiscal deficit by 3.8 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) between 2021 and 2023. Significantly, in 59 countries the fiscal consolidation planned is larger than the size of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that at least in a sizeable number of countries, IMF advice on fiscal consolidation exceeds the size of government response to the crisis.

It is sometimes argued that the reduction of fiscal deficit and public debt should allow governments the fiscal space to expand government expenditure when the need arises. For instance, in the fourth review under the Extended Credit Facility for Guinea (report 20/111), IMF staff make the following recommendation:

“

Figure 4: Incidence of austerity measures: Government finance (Number of country reports)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on 148 IMF country reports in 2020.

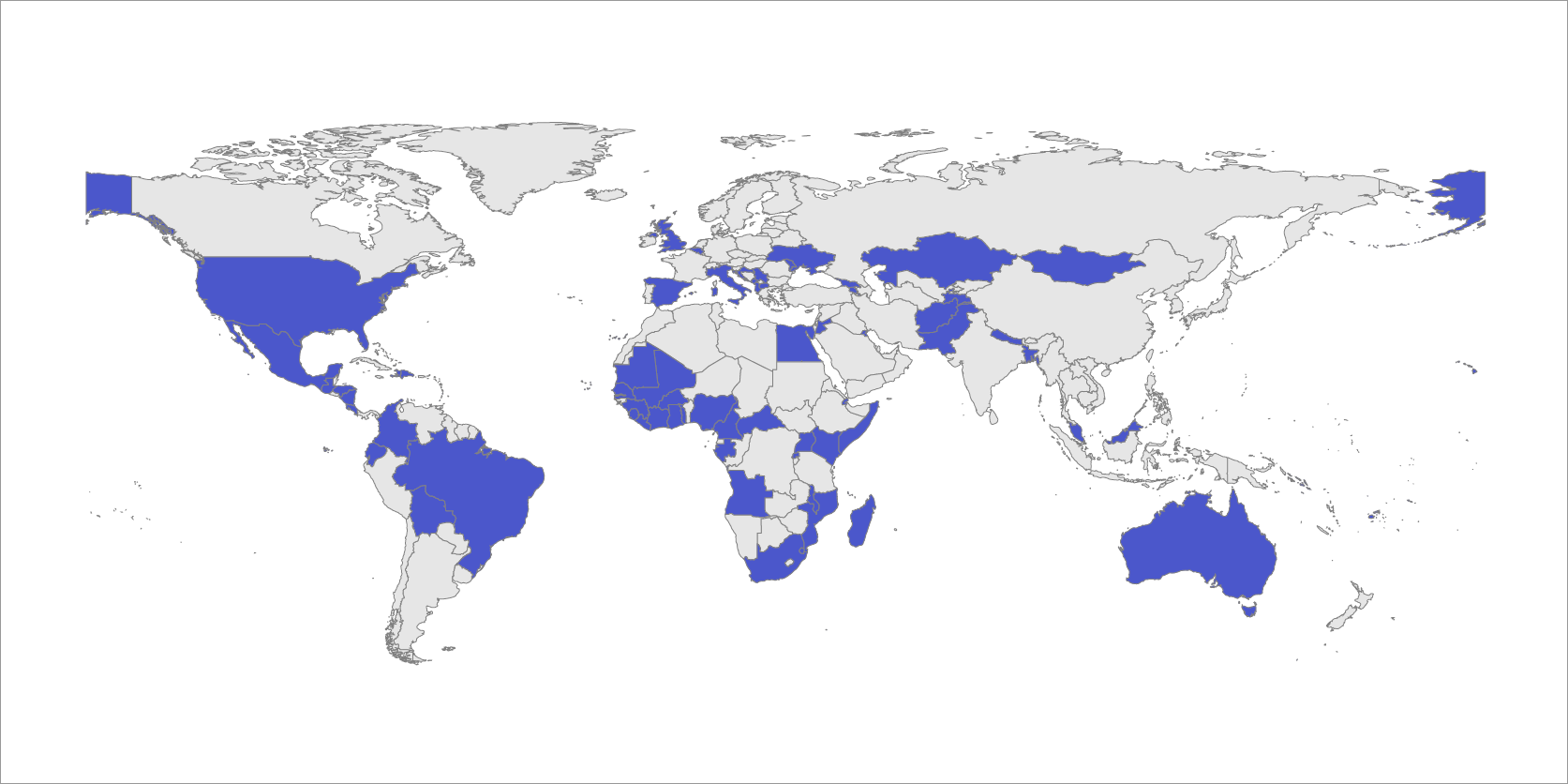

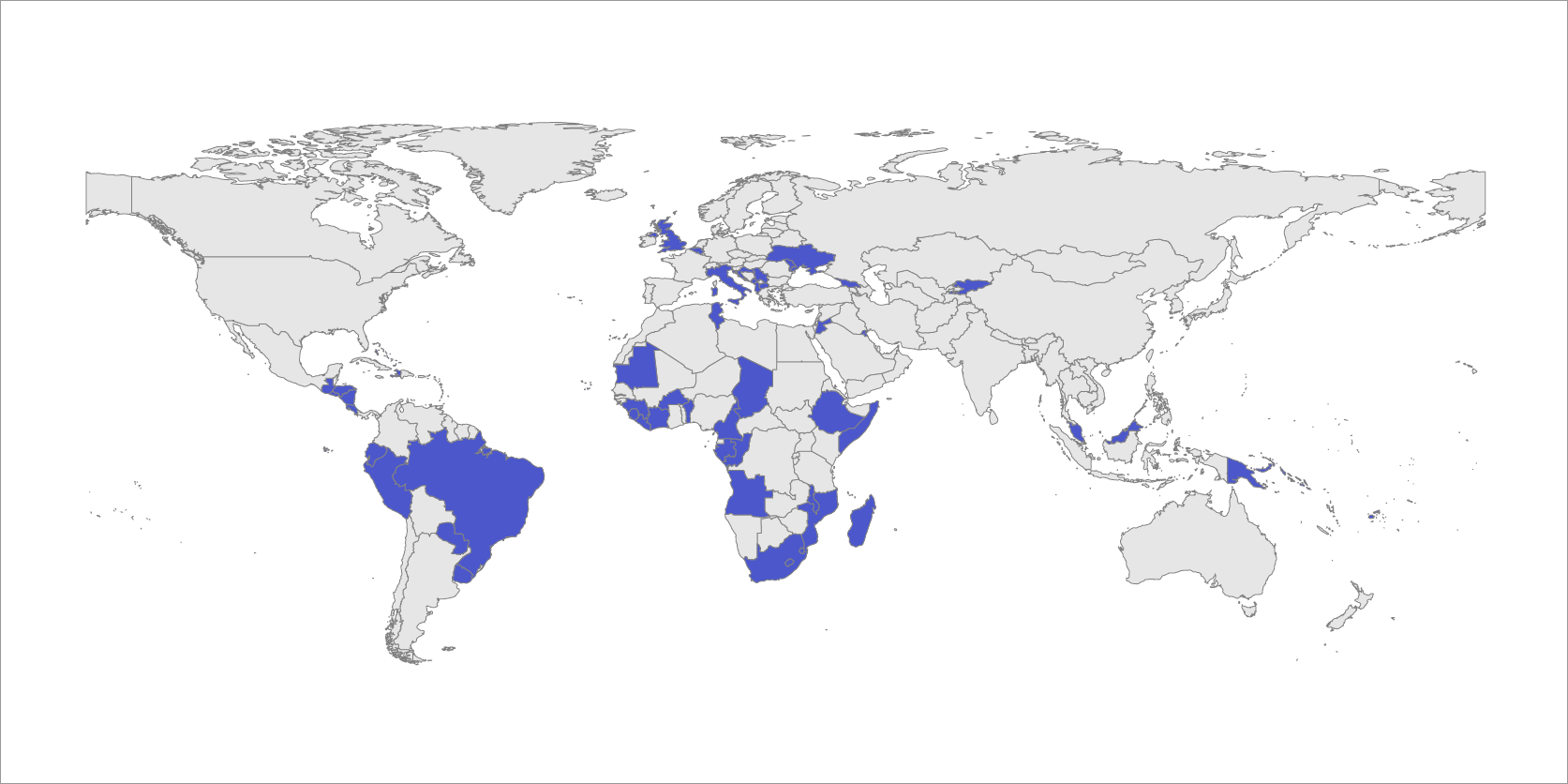

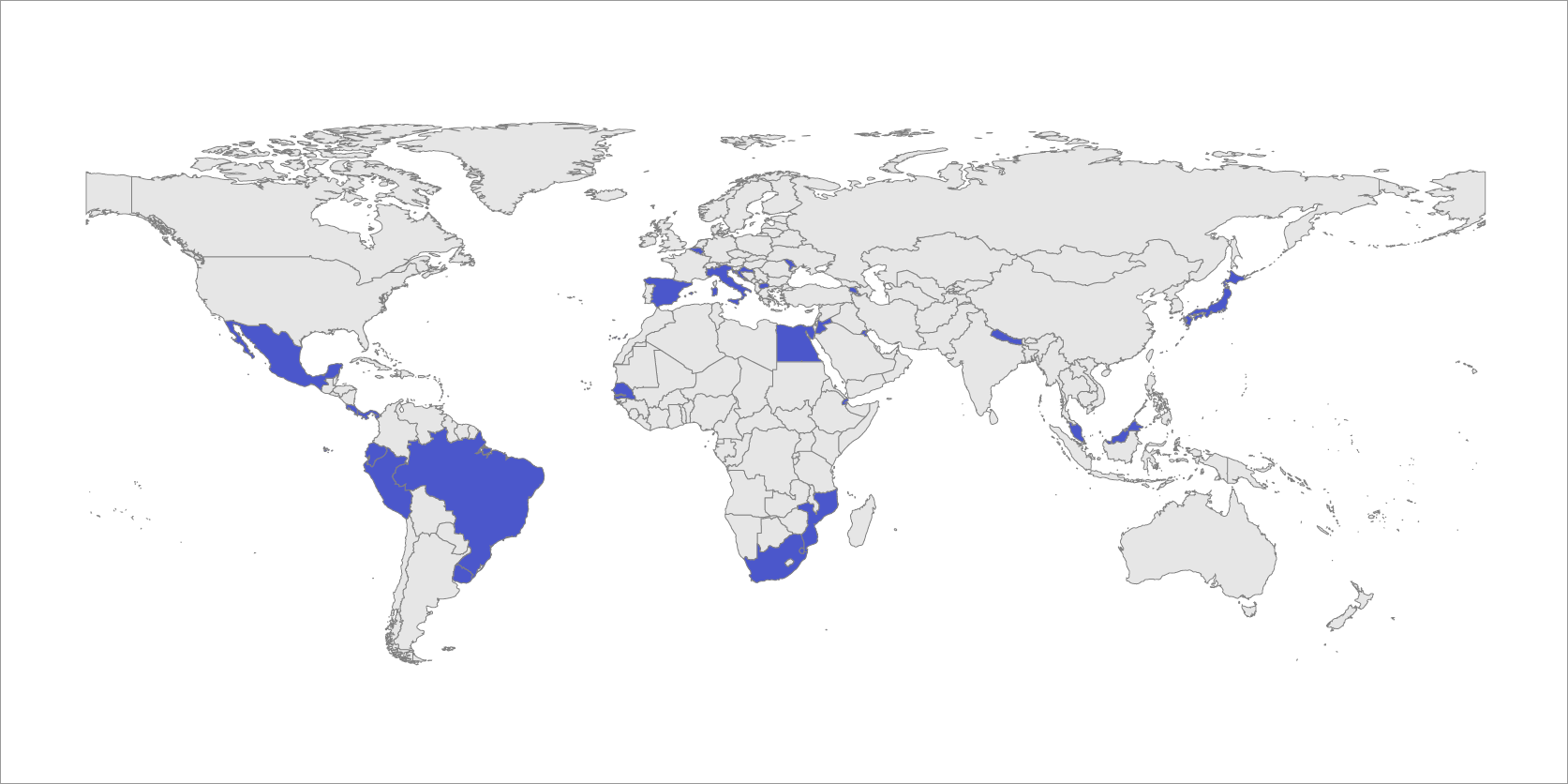

Figure 5 shows countries in which the IMF recommended that governments take measures to achieve fiscal consolidation.

Figure 5: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation of fiscal consolidation in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Recommendations regarding government expenditure on social policies

Social spending floors

In 2019, the IMF revised its strategy for engaging with social spending, emphasizing inclusive growth through the use of social and pro-poor spending “floors” in IMF-supported programmes (IMF 2019). The strategy reflects concerns about rising inequality and the need to support vulnerable groups, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. In low-income countries, the IMF should “wherever possible” include minimum floors on social and other priority spending in programmes supported by Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust facilities (IMF 2018). Social spending is defined as spending on education, health and social protection — with social protection comprising social safety nets (or social assistance) and social insurance; other priority spending generally includes high-priority projects that support national poverty reduction and growth strategies (IMF 2018, p. 3). The IMF strategy for engagement on social spending argues that the Fund’s engagement with social spending should take into account the “macro-criticality” of social programmes (IMF 2019). The channels through which social spending becomes macro-critical are identified by the IMF to be “fiscal sustainability, spending adequacy, and spending efficiency”.6

It is encouraging that in 2020, 17 of the 28 country reports reviewed that discussed the indicative target of a floor on social spending and poverty-reducing expenditure indicated that the social spending indicative target was met. On the other hand, 11 of the 28 reports indicated that the social spending target was not met, meaning that social spending was lower than the minimum expenditure target established for social programmes. Yet in 9 of these 11 reports in which IMF staff indicated that social expenditure had fallen short of its floor, IMF staff still recommended fiscal consolidation.

Health-care expenditure

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the need to invest in health-care services, while also drawing attention to the challenges that countries face in recruiting, deploying, retaining and protecting sufficient well-trained health workers to ensure the delivery of quality health-care services.

Despite progress across the world over the past decade, barriers to accessing health care remain in the form of out-of-pocket payments on health services; physical distance; limitations in the range, quality and acceptability of health services; long waiting times; and opportunity costs such as lost working time. While most countries have made progress in increasing population coverage and almost two thirds of the global population are protected by a health-care scheme, people in the lowest income quintiles and in rural areas often continue to face challenges in meeting their health needs without hardship (ILO 2021). Collective financing, broad risk-pooling and rights-based entitlements are key principles for supporting effective access to health care for all. Investing in the availability of quality health-care services is also crucial and requires long-term planning. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed the insufficient levels of investment in health-care infrastructure in many countries, exacerbated by fiscal austerity over many years.

Through its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF has actively supported the expansion of health-care expenditure in many countries so that governments have the financial resources to scale up testing capacity; secure personal protective equipment for their health-care workers; purchase life-saving equipment to supplement health-care capabilities in a variety of countries; and purchase, distribute and administer vaccines. The IMF classified health-care expenditure as a priority social expenditure and during this pandemic also prioritized higher spending by governments on health care, including on the wages and number of health-care workers, even if there was a freeze on wage hikes for other categories of workers. The IMF also supported this higher level of expenditure and the introduction of supplementary budgets in many countries, even if it meant a worsening of the fiscal balance. Increase in health-care expenditure was the second most recommended policy action to governments – found in 133 of 148 country reports of 2020.

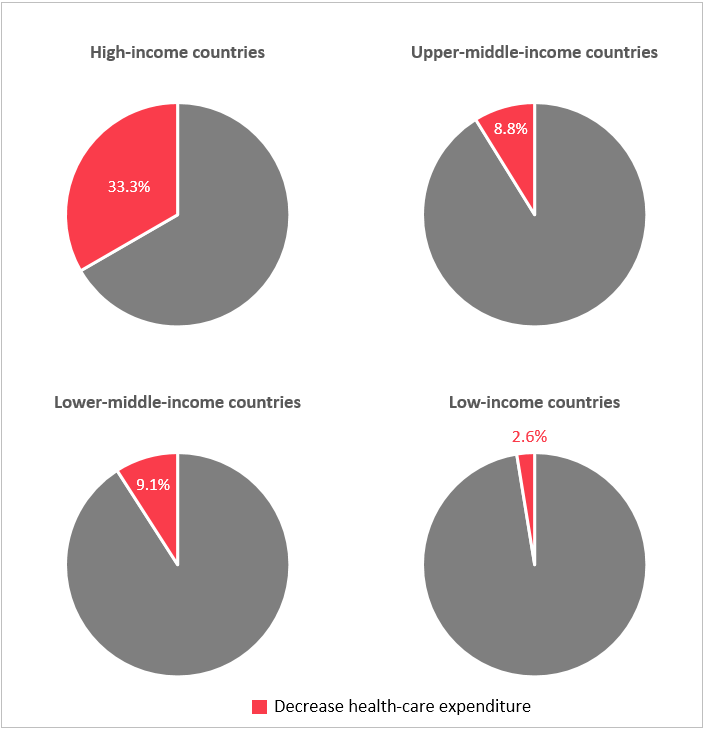

However, a closer reading of the reports reviewed reveals a more cautious stance with regard to the proposed timeline for the expansion of health-care spending, sometimes seeing the need for only a temporary increase. In some instances, the IMF explicitly advocated reducing some expenditures on health care once the pandemic was under control. Figure 6 shows the distribution of IMF advice on health-care expenditures across country income groups. In 138 reports, the IMF made 141 recommendations on health-care expenditure. The highest incidence of advice to contain expenditure on health care was in reports on high-income countries (5/15), followed by reports on lower-middle-income countries (4/44) and reports on upper-middle-income countries (3/34), with the lowest incidence in reports on low-income countries (1/39).

Figure 6: Recommendation on decreasing health-care expenditure by country income groups

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020

Here are some examples of the reports in which IMF staff recommended reducing health-care expenditure.

-

Article IV report for Belgium (report 20/91) :Growth-friendly spending reforms should underpin the medium-term adjustment. A sustained medium-term effort to reduce primary spending while improving its efficiency can support deficit targets and reorient the budget toward more growth-friendly areas. Reforms should focus on containing medium-term healthcare costs, bolstering the sustainability of the pension system, improving the targeting and labor-market incentives of social benefits, strengthening the efficiency of subsidies, and reducing duplication in the public administration. ” And “Healthcare spending is high relative to peers …in the medium run, a strategy is needed to contain costs by strengthening overall cost controls. -

Article IV report for Brazil (report 20/311) :Cutting personnel costs and addressing rigidities in central and regional budgets, including through less indexation and earmarking, will enable substantial efficiency gains. Priority actions include: ... Removing minimum requirements for state-level spending on education and health, or at the very least creating a joint (instead of the current separate) minimum requirement as proposed in the Federative Pact.

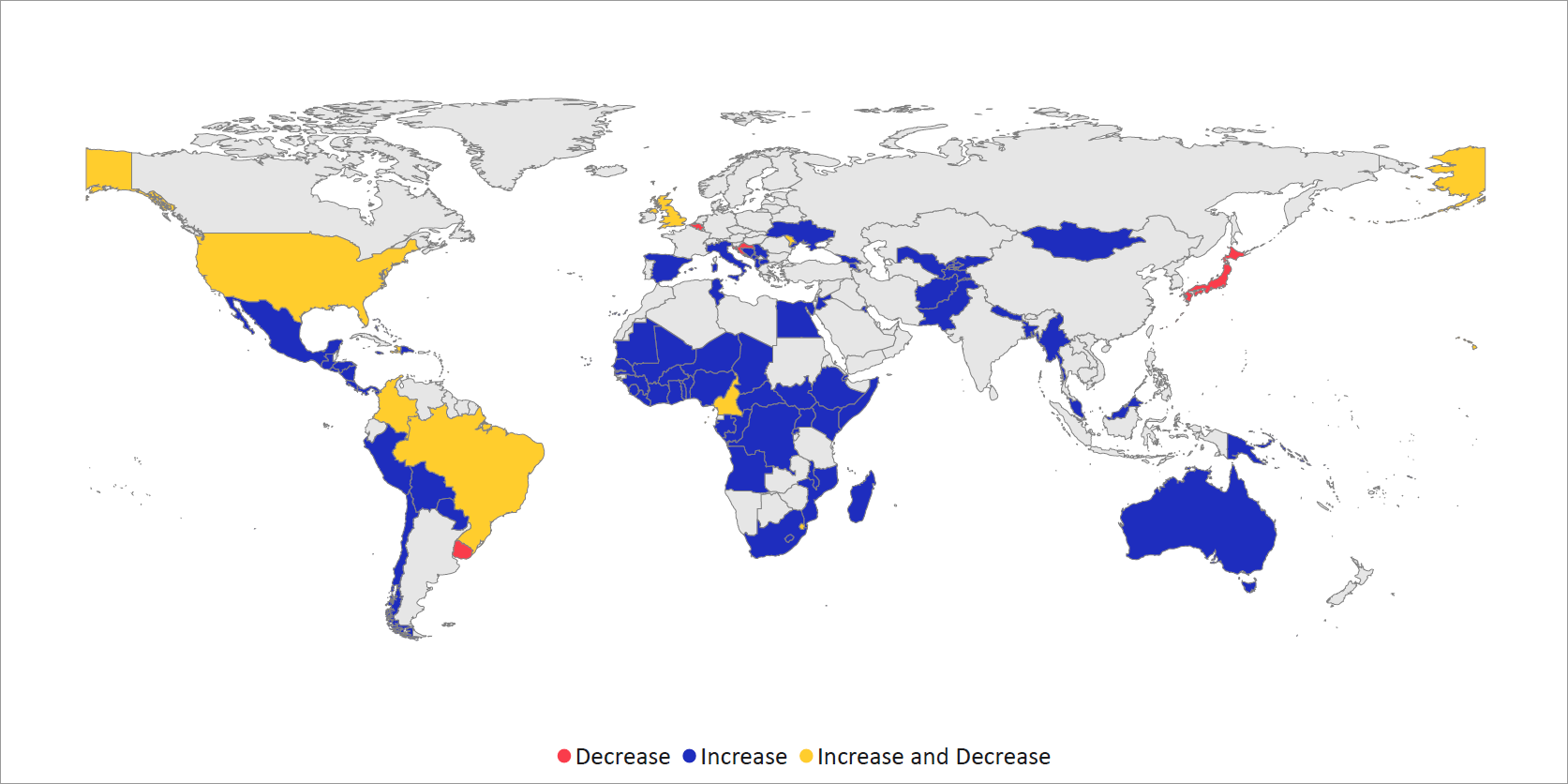

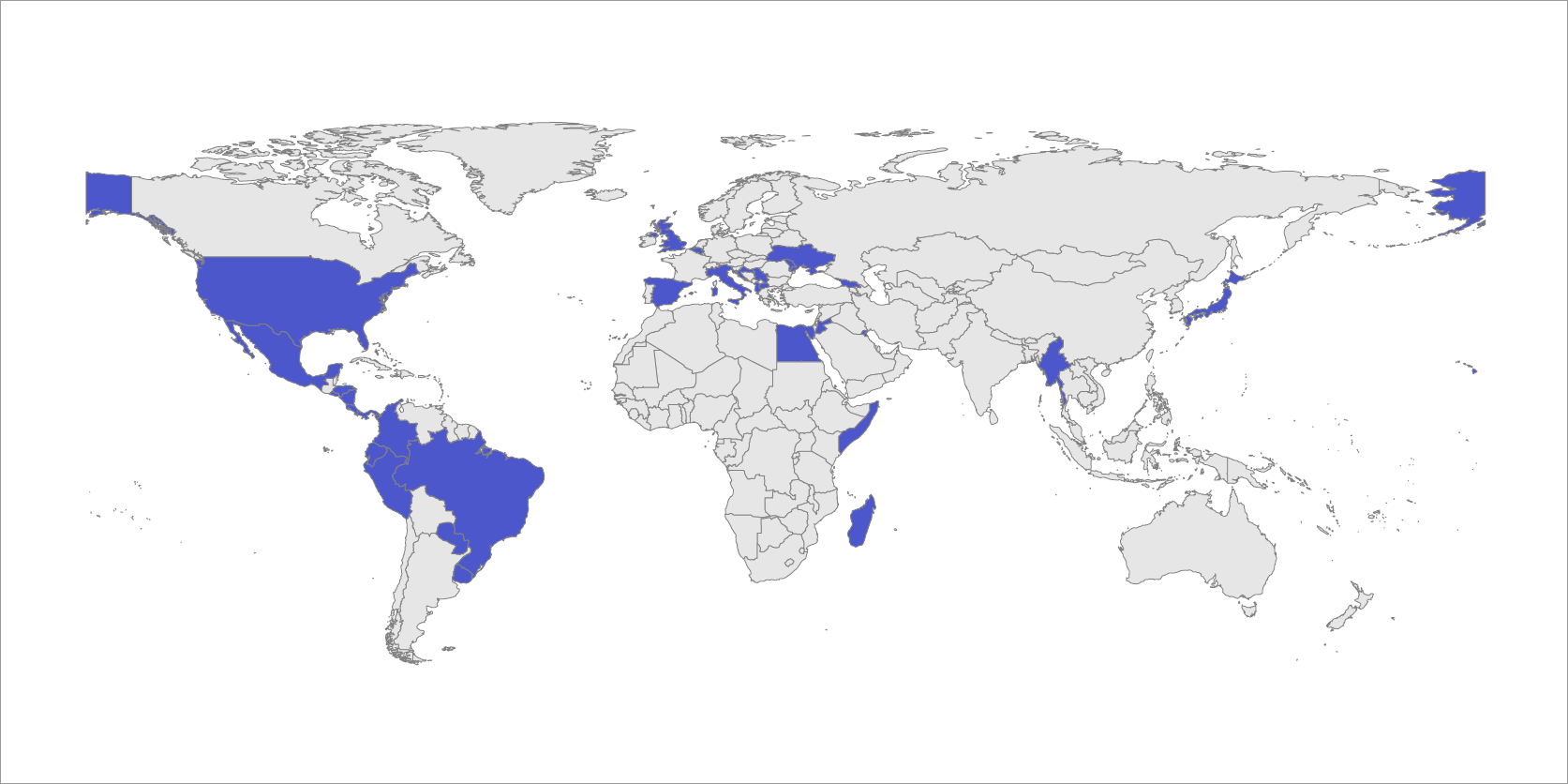

Figure 7 shows the distribution of IMF recommendations on health-care expenditure by country. The countries shaded blue are countries in which the IMF recommended increasing health-care expenditure; the countries shaded in red are those in which the IMF recommended decreasing health-care expenditure; and the countries shaded in yellow are those for which the IMF recommended increasing some health-care expenditures and reducing others.

Figure 7: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation on health-care expenditure in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020

Insufficient funding is a key determinant of persistent health-care deficits. It results in increased risk of financial hardship and lack of effective access to adequate health-care services. Hence, what most countries need is not only a temporary increase in health-care expenditure but also sustained investments to support effective access to quality health-care for all.

Cash benefits

When the COVID-19 crisis hit the world in early 2020, only 46.9 per cent of the global population was effectively covered by at least one social protection benefit (Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 1.3.1), while the remaining 53.1 per cent – as many as 4.1 billion people – were wholly unprotected. Behind this global average, there are significant inequalities across and within regions, with coverage rates in Europe and Central Asia (83.9 per cent) and the Americas (64.3 per cent) standing well above the global average, while Asia and the Pacific (44.1 per cent), the Arab States (40.0 per cent) and Africa (17.4 per cent) have far more pronounced coverage gaps (ILO 2021a).

The crisis led to a vigorous yet uneven global social protection response, with many countries introducing, scaling up or adapting their social protection measures to protect hitherto uncovered or inadequately covered population groups. The measures adopted covered all functions of social protection (from income and job protection to health coverage and child and family benefits). Approximately three quarters of these measures comprised non-contributory responses (including social assistance), while the remainder were delivered through contributory schemes (ILO 2021b).

Higher-income countries were in a stronger position to mobilize their existing social protection systems — including both contributory social insurance and non-contributory tax-financed schemes — or introduce new emergency measures to contain the impact of the crisis on health, jobs and incomes. Mounting a response was more challenging in lower-income contexts, which had more fragmented social protection systems and less room for policy manoeuvres, especially in terms of macroeconomic policy.

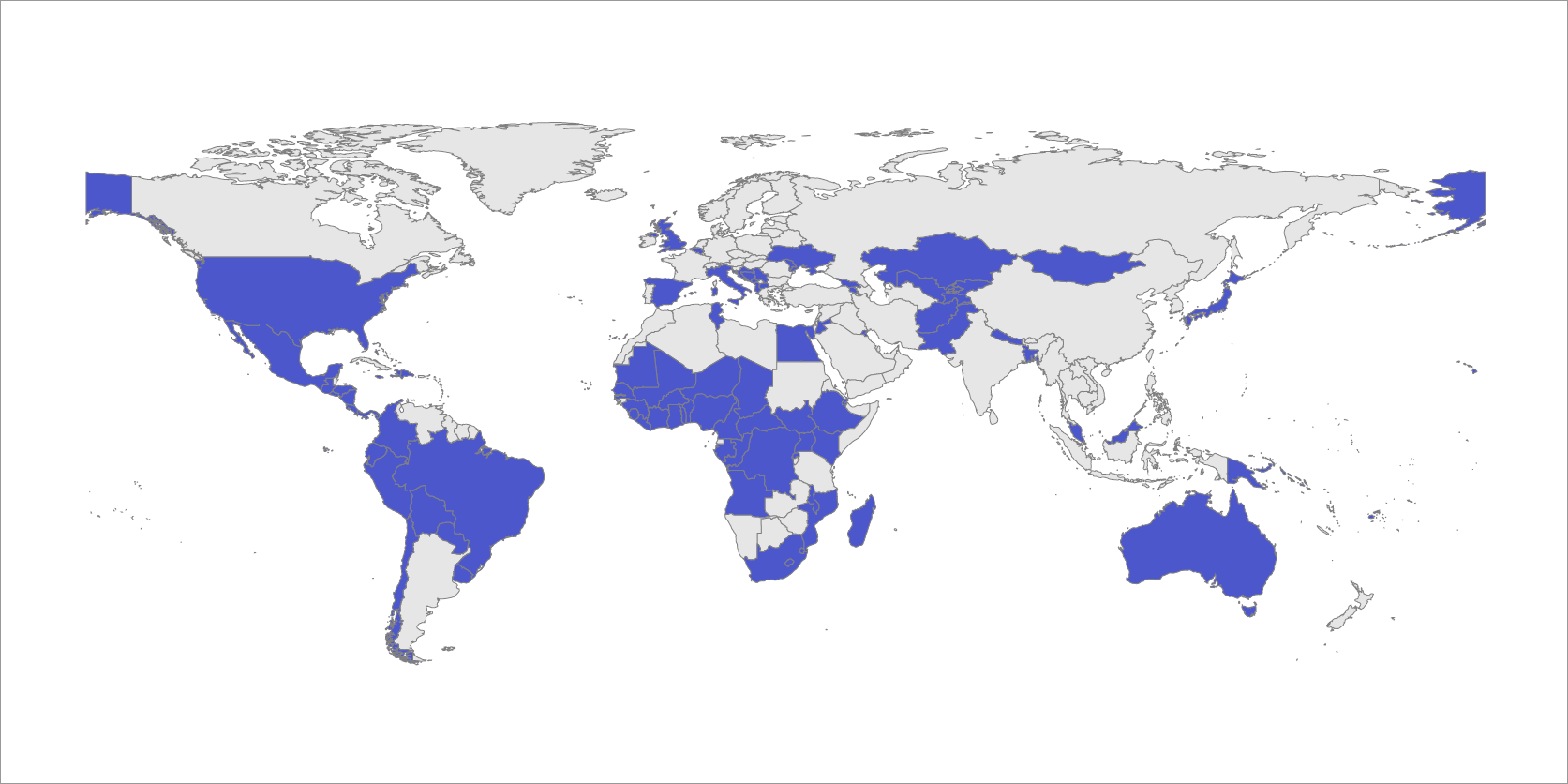

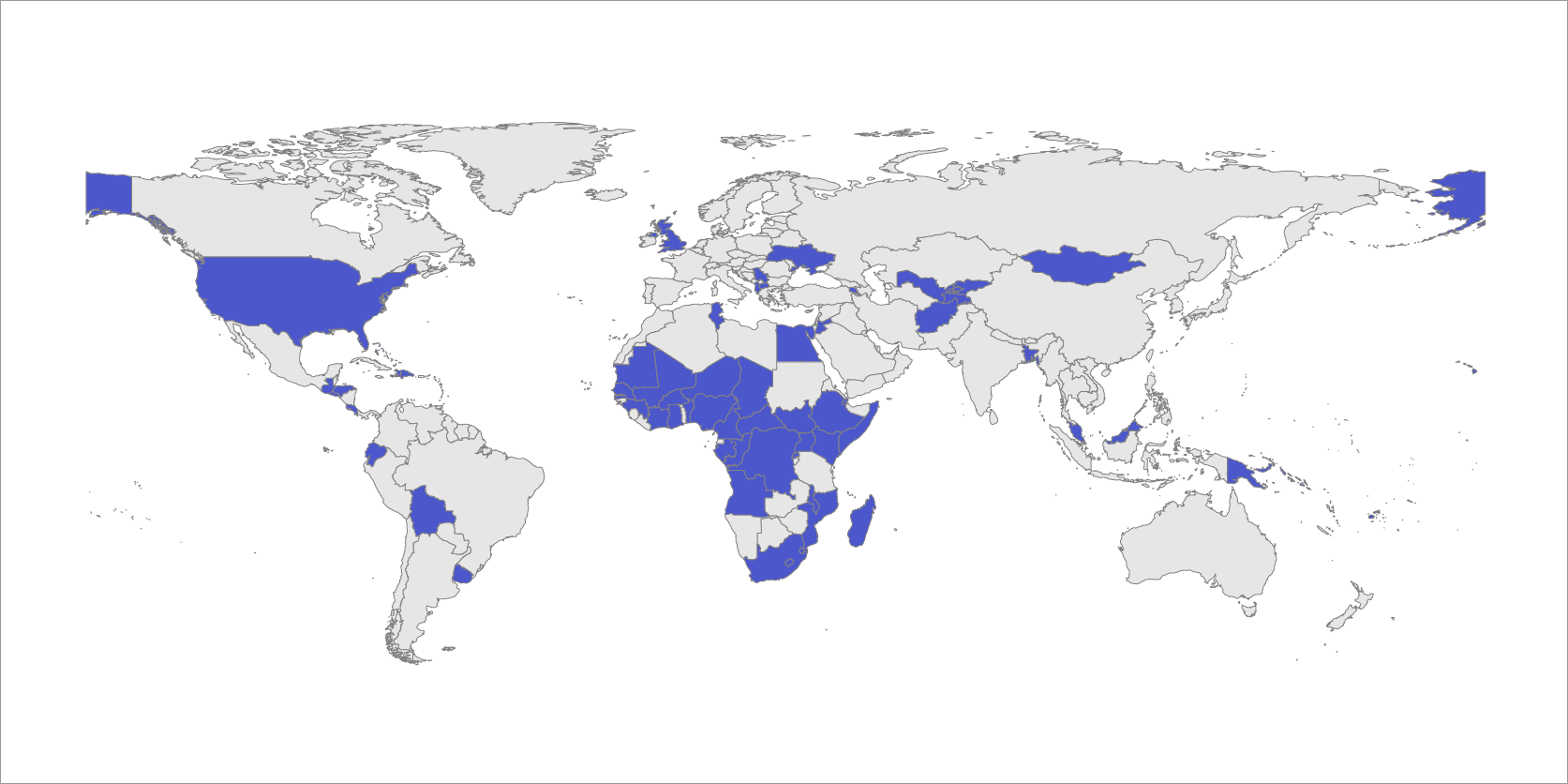

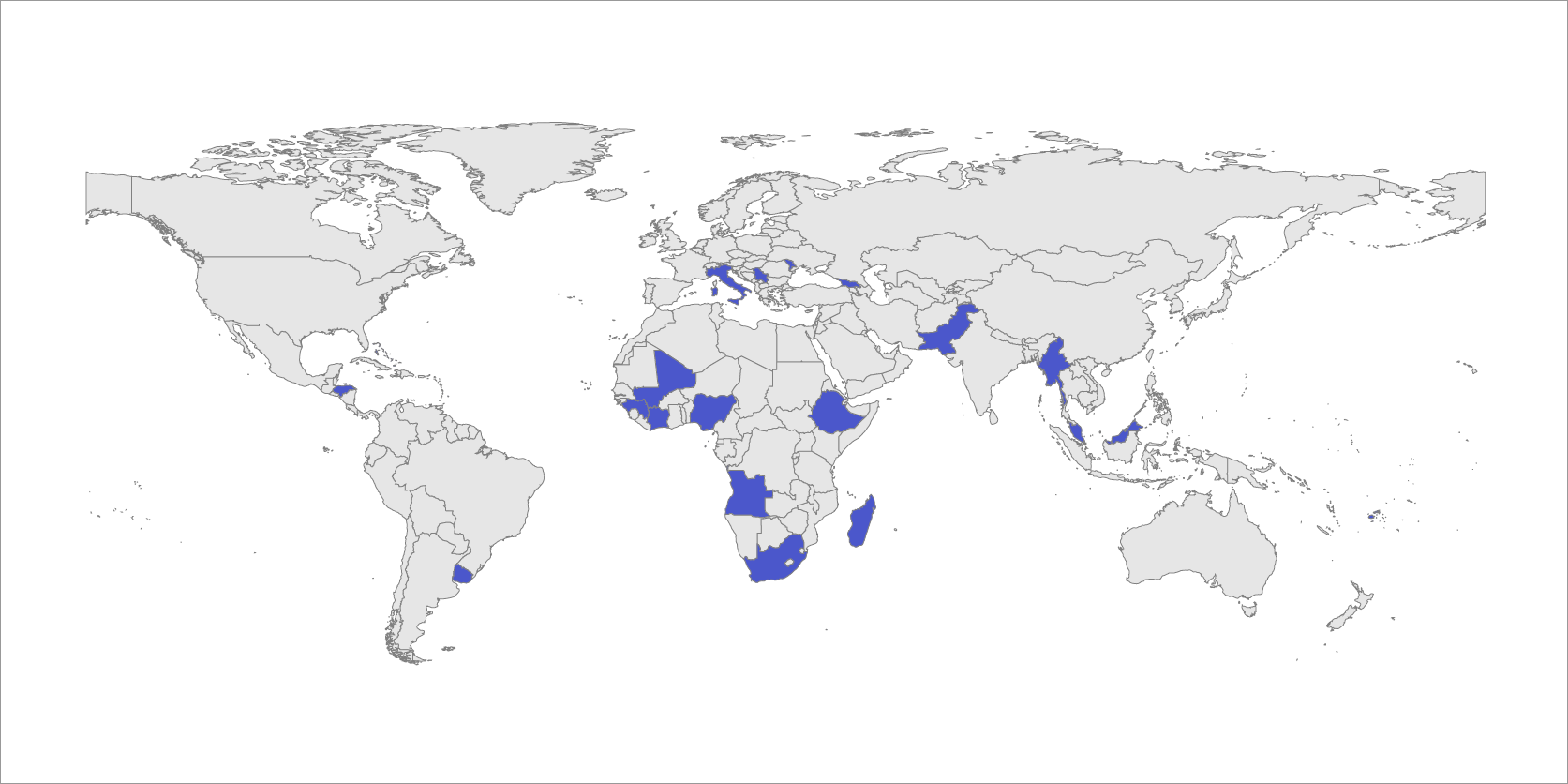

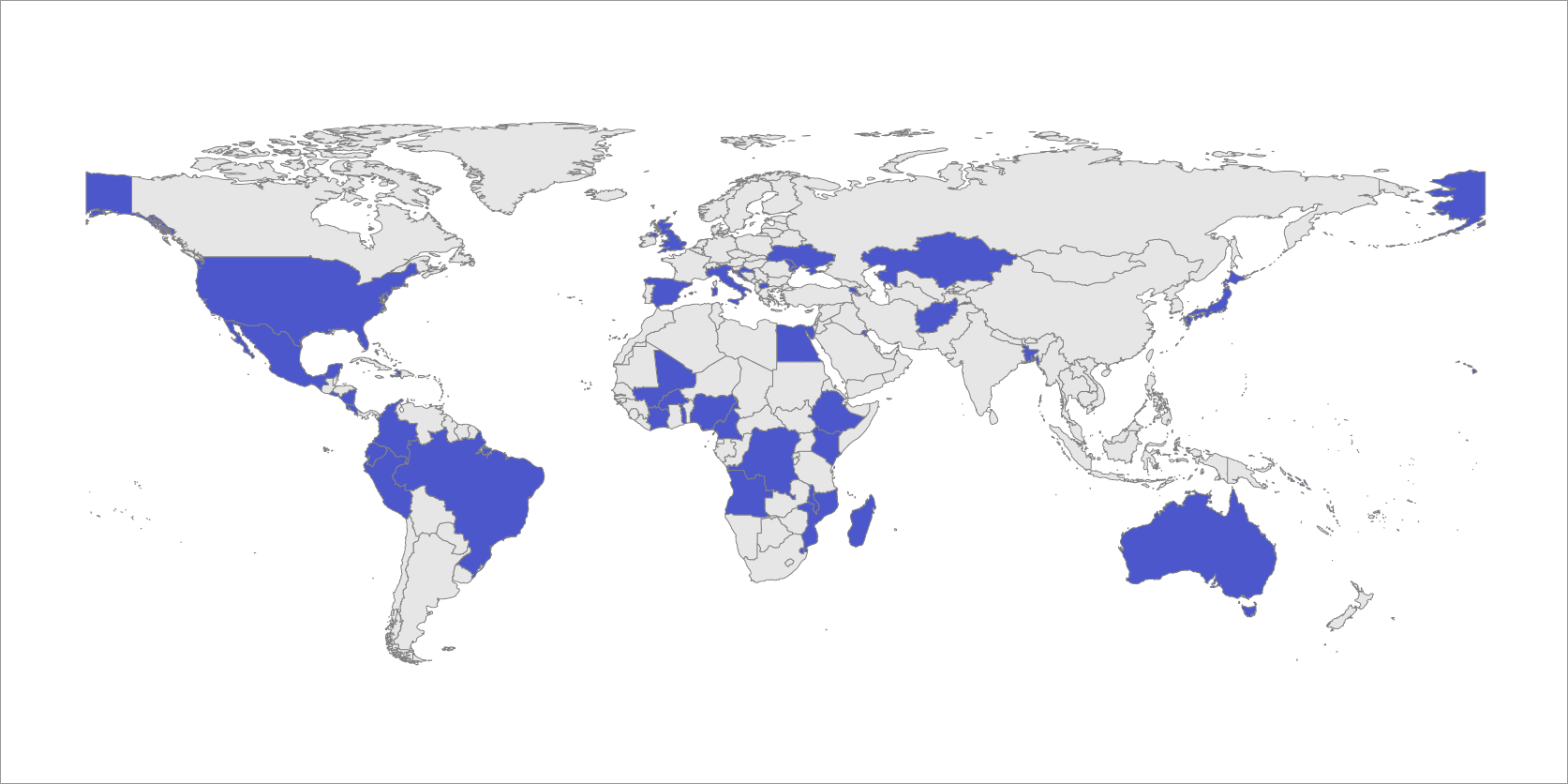

As noted above, in response to the pandemic, many governments instituted or expanded the level of social assistance schemes or programmes to households (sometimes referred to as cash transfers) and IMF staff in their reports supported such measures or actively recommended them. In fact, 6/15 reports on high-income countries, 17/39 reports on upper-middle-income countries, 27/49 reports on lower-middle-income countries and 29/44 reports on low-income countries contained a recommendation to expand cash transfer programmes. Figure 8 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended increasing the level or scope of cash transfers.

Figure 8: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to Increase spending on cash transfers in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Below are a few examples of IMF recommendations regarding cash transfers.

-

Article IV consultation for Brazil (report 20/311) :Despite already high public debt, Brazil’s fiscal support was among the largest for G20 countries and twice the EM average. An important element of the government support was in the form of cash transfers (Auxílio Emergencial or Emergency Aid) to informal workers and poor households. The authorities also increased health spending, provided financial support to subnational governments, extended government-backed credit lines to small businesses, and introduced employment retention schemes. -

Request for disbursement under the Rapid Credit Facility for Senegal (report 20/108): On the expenditure side, expenditure reallocation and savings on fuel subsidies will allow to support particularly hard-hit sectors of the economy and households, including through food aid and cash transfers to vulnerable households, and expediting payments of unmet obligations. On cash transfers, the authorities plan to leverage the existing “bourses familiales” program by first extending support beyond the current 300,000 beneficiary households to the full 580,000 households registered as vulnerable, and, with World Bank support, to further extend this support to a total of 1 million households including those newly affected by the pandemic.

While extending the coverage and increasing the benefit levels of cash transfers, the IMF often recommended that the “safety net” should be both temporary and better targeted to generate fiscal savings. With regard to the temporary nature of these measures, if recipients know that such support is temporary, the incentive to save at least some of the transfer in order to smooth consumption may mean that the impact of the economic stimulus (to help retain jobs) will be muted. Moreover, given the extensive coverage gaps in social protection, without continued support for social protection expenditure, many countries could face the possibility of a “cliff fall” scenario, whereby emergency social protection support ends prematurely and abruptly before a full jobs-rich recovery. Interestingly, this “cliff fall” scenario was recognized in the above-mentioned IMF report on Brazil (2020 Art. IV consultations), which cautioned that

As for the recommendation on targeting transfers to the most vulnerable, two sets of issues deserve attention. First, there is a long-standing debate about the paradoxical impact on poverty and inequality of targeting transfers to poor individuals and households. Evidence from a wide range of institutionalized welfare states shows that the more countries target benefits only to poor individuals and households, the less likely they are to reduce poverty and inequality (Korpi and Palme 1998) – the paradox of redistribution. To understand this paradox, it is useful to take note of the fact that arguments in favour of low-income targeting and flat-rate benefits have focused on the distribution of money actually transferred but they have overlooked two basic factors: (a) the size of the redistributive budget, which is not necessarily fixed, and depends on the type of social protection system that is in place; and (b) a political economy logic, which shows that there is a trade-off between the extent of low-income targeting and the size of redistributive budgets. The less likely non-poor individuals and households are to benefit from social protection, the less likely they are to pay both contributions and taxes to sustain it (Mkandawire 2005). In other words, in order to increase the size of the redistributive budget it is imperative to expand the reach of the social protection system. There is also a considerable body of research, largely focused on developing countries, showing that targeting social transfers can lead to considerable exclusion errors (Kidd and Athias 2019; Brown et al. 2016; Ravallion 1999).

Second, with regard to the specific COVID-19 pandemic, while the crisis disproportionately affected certain groups, it also illustrated that without comprehensive and adequate social protection, anyone can fall into poverty and insecurity. The crisis exposed the shortcomings of limited coverage and low benefit levels, with narrow targeting, problematic proxy means tests and behavioural conditions, especially in contexts where large segments of the population are vulnerable and administrative capacity is constrained to an even greater degree than in non-crisis times

Nevertheless, in 2020 IMF staff consistently recommended that all cash transfer programmes and social services extended during the pandemic should be both temporary and targeted, as exemplified below.

-

Request for 42-month arrangement under the Extended Credit Facility for Afghanistan (report 20/300): To protect the level and improve the efficiency of social spending over the medium term, the authorities plan to build a targeted social safety net for which they intend to seek donor technical and financial assistance. The program will aid these efforts by creating fiscal space. -

Request for disbursement under the Rapid Credit Facility and for purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument for the Comoros (report 20/152): In addition to expanding healthcare resources, the authorities could consider giving targeted and temporary support for affected households, particularly among the most vulnerable, through direct cash transfer or other feasible instruments. -

Request for purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument for Jordan (report 20/180): Staff supports the authorities’ fiscal strategy to respond to the shock. The authorities recognize that they have limited fiscal space, and that the measures announced should be temporary and targeted. -

Seventh review under the Extended Fund Facility Arrangement for Georgia (report 20/322): Social assistance will include temporary transfers to workers in the formal and informal sectors and self-employed who lost income, additional direct transfers to vulnerable families with children, and utility subsidies to low energy consumers in January and February 2021; this last measure is expected to reach the informal sector.

Figure 9 shows the regional distribution of countries for which the IMF recommended that new or expanded cash transfers and/or social programmes should be temporary and targeted or that the existing social safety net should be better targeted in order to achieve fiscal consolidation. It is worth underlining that when new programmes are temporary, they are difficult to institutionalize and thus to scale up support during a crisis, which will render countries dependent on ad hoc measures and external support.

Figure 9: Regional distribution of IMF recommendations to increase targeting in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

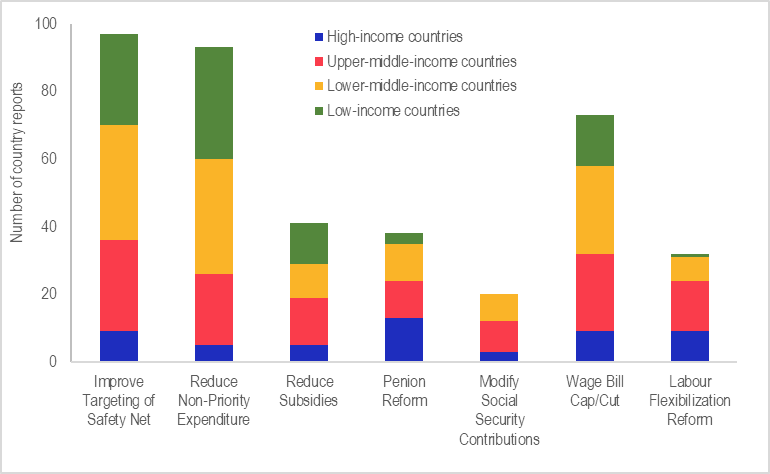

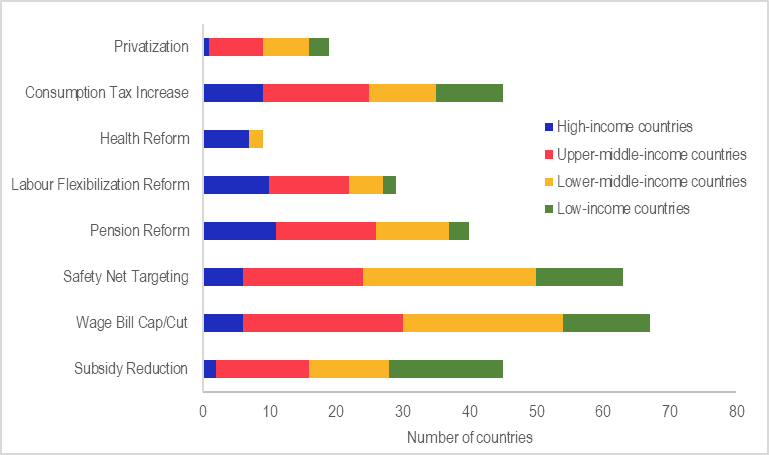

Figure 10 shows the incidence of austerity measures recommended by the IMF in its 2020 country reports. It can be seen that the recommendation to target social programmes and cash transfers was found in 9/15 or 60 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 27/39 or 69.2 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries, 34/49 or 69.4 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries and 28/44 or 63.6 per cent of reports on low-income countries.

Figure 10: Incidence of austerity measures recommended by the IMF in 2020 (Number of country reports)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on 148 IMF country reports in 2020.

Reduction of non-priority expenditures

In several country reports, the policy discussion suggests that, in order to increase fiscal allocations to health care, governments should consider reducing non-priority expenditures. The recommendation to reduce non-priority expenditures also appear when there are recommendations to achieve fiscal consolidation. In order to achieve fiscal consolidation, IMF staff recommended reducing non-priority spending in 93 of 148 reports, involving the reduction of a variety of both current and capital expenditures. In many instances, the reports are not specific about what constitutes non-priority expenditure, whether current or capital. None of the reports recommended reducing military expenditure. Non-priority expenditure (to be reduced or postponed to create fiscal space for additional spending on health and targeted cash transfers) could also be understood to mean social expenditure that is not targeted to the poor — the IMF Strategy on Social Spending Floors (IMF 2019) is supportive of programmes that are narrowly targeted to the most vulnerable, despite accepting that countries might also wish to put in place universal or categorical benefits. Below we cite a few examples of references to reducing specific expenditures.

-

Request for disbursement under the Rapid Credit Facility for the Republic of Mozambique (report 20/141): If the economic situation were to worsen, the government should prepare a contingency plan, including notably (i) further increases as needed of health spending by reallocating non-essential expenditure and limiting public wage increases and hiring of non-essential workers, and (ii) additional tax relief. -

Sixth review under the Extended Credit Facility Arrangement for Benin (report 20/175): If domestic financing at reasonable terms is unavailable, further expenditure rationalization measures could be taken to make space for priority spending. This would entail slowing down further the implementation of capital projects, which may occur anyway if the domestic outbreak halts economic activity.” -

Third review under the Stand-By Arrangement and Modification of Performance Criteria for Armenia (report 20/318): An expenditure review, planned for early 2021, will identify efficiencies in current spending and is intended to feed into the 2022 budget process. The identification of efficiencies should support fiscal consolidation, allow current spending to return to its pre-crisis level, while ensuring space for priority social and investment spending. -

Request for purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument for Bolivia (Plurinational State of) (report 20/182): Debt should start falling over the medium term as the government pursues a medium-term reform plan that will eliminate lower-priority public spending and steadily reduce the primary deficit.”

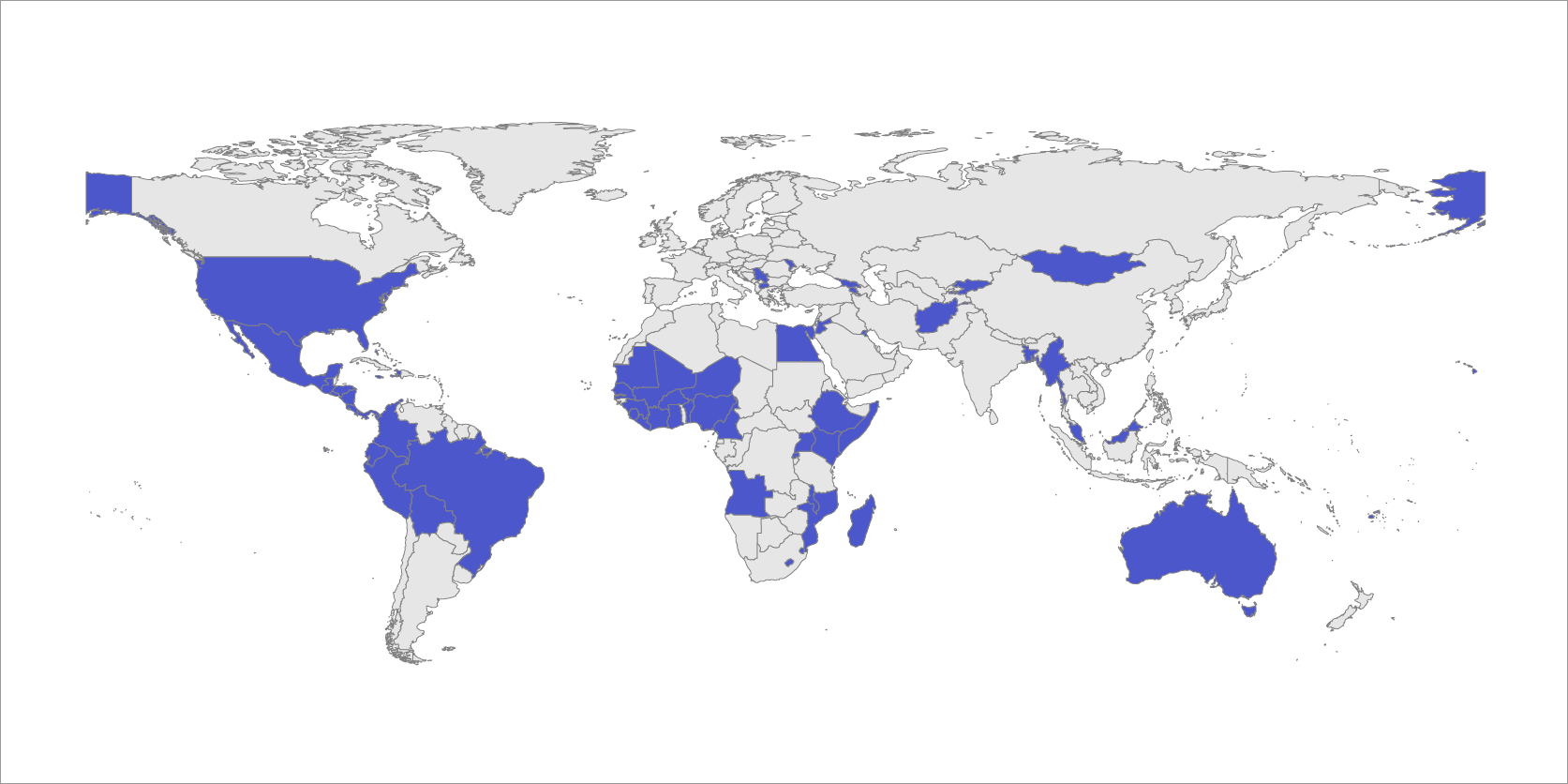

IMF staff recommended a reduction in non-priority spending in 5/15 or 33.3 per cent of reports for high-income countries, 21/39 or 53.8 per cent of reports for upper-middle-income countries, 34/49 or 69.4 per cent of reports for lower-middle-income countries and 33/44 or 75 per cent of reports for low-income countries (figure 10). Figure 11 shows the regional distribution of countries in which the IMF recommended a reduction of non-priority expenditure in 2020.

Figure 11: Regional distribution of IMF recommendations to reduce “non-priority expenditures” in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Reduction of subsidies

Since 2010, reducing subsidies on fuel, electricity, food and agriculture has been a prevalent policy, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa region and in sub-Saharan Africa. The reduction of food subsidies in particular is often accompanied by the development of a basic “safety net” as a way of compensating the poorest, who are most likely to be the worst affected. However, in practice this is an insufficient compensatory measure given that these subsidies are universal and benefit all households, while remedial basic safety nets only benefit a few of those most affected. In developing countries, the so-called middle classes have low incomes and are very vulnerable to price increases (ESCWA 2019; Cummins et al. 2013). Not surprisingly, the sudden removal of energy subsidies and consequent increases in prices have sparked protests and violent riots in many countries (ILO 2017; Ortiz and Cummins 2019).

There are several important policy lessons that must be taken into account (ILO 2017). First, the issue of timing is key: while subsidies can be and frequently are removed overnight, developing social protection systems takes a long time, particularly in countries where institutional capacity is weak even in “normal” times. Therefore, there is a high risk that subsidies will be withdrawn and populations will be left unprotected, making food, energy and transport costs unaffordable for many households. Second, targeting the poor excludes other vulnerable groups. As noted above, in most developing countries those who may be hovering above the poverty line or even well above it still have very low incomes and are vulnerable to price increases, so that a policy to remove subsidies that allows only targeted transfers for the poor may punish low-income groups as well as many among the middle classes. Third, although the savings resulting from reductions in energy subsidies may be sizeable and allow countries to make important strides in developing universal social protection systems, in practice only a fraction of the savings that have accrued from the reduction of fuel subsidies has been allocated to the usual minimal compensatory social protection measures (ILO 1997).

The reduction of subsidies is also evident in the recommendations of the reports reviewed for this paper. As figure 10 shows, in 2020 advice on reducing subsidies was included in 5/15 or 33.3 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 14/39 or 35.9 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries, 10/49 or 20.4 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries and 12/44 or 27.3 per cent of reports on low-income countries. This constituted 27.9 per cent of all reports in 2020. The following are some examples of advice to reduce subsidy expenditures given by IMF staff.

-

Fourth review under the Extended Credit Facility Arrangement for Guinea (report 20/111): Achieving the programmed basic fiscal surplus in 2020 will contribute to containing inflation and preserving debt sustainability. Mobilizing additional tax revenues and reducing electricity subsidies will create fiscal space to scale-up growth-supporting public investments and strengthen social safety nets. -

Third review under the Stand-By Arrangement and arrangement under the Stand-By Credit Facility for Honduras (report 20/319): Given uncertainty about the outlook, the authorities are prepared to respond to eventual contingencies and risks. If downside risks materialize, for example, due to a recurrent pandemic wave or another climate-related event, they plan to reprioritize expenditure as needed to reduce non-priority spending—as done in the past, and notably during the pandemic, with a focus on spending that is not included in priority social programs or critical subsidies (e.g., on electricity consumption). -

Request for Purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument for South Africa (report 20/226): Staff recommended a gradual and growth-friendly but sizable reduction of the consolidated government deficit. This consolidation will require implementation of fiscal measures of about 5–5.5 percent of GDP over the next five years, which alongside the impact of the growth recovery would allow the deficit to decline to average levels of about 4.5 percent of GDP in the medium term. Needed measures include limiting increases in recurrent expenditure, mainly compensation, transfers to state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and ill-targeted subsidies, while pursuing a recovery of productive public investment and protecting outlays for health and education and well-targeted social assistance.

Figure 12 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended the reduction of subsidy expenditure.

Figure 12: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to Reduce Subsidies in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Table 4 shows the breakdown of the type of subsidy expenditure that the IMF recommends should be reduced. The most recommended subsidy reduction was the reduction of fuel or energy subsidies, followed by the reduction of electricity subsidies and the reduction of subsidies to state-owned enterprises.

Table 4: Number of country reports with recommendation to reduce subsidy expenditure by subsidy type, 2020

|

Type of subsidy |

Number of country reports |

|---|---|

|

Energy |

22 |

|

Electricity |

7 |

|

State-owned enterprises |

7 |

|

Agriculture |

4 |

|

Water |

2 |

|

Other |

9 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Removing universal subsidies with the promise of making targeted cash transfers available to the poorest entails some risks – especially where transfer programmes are not anchored in law, remain limited in scope and provide low benefit levels that get eroded over time (due to lack of indexation), not to mention their heavy administration costs, arduous application procedures and the risk of exclusion errors. The reduction of energy subsidies, however, may provide an opportunity to develop social protection systems for all, including floors. Fuel subsidies are generally large and should allow governments to develop comprehensive universal social protection systems for all citizens and not just minimal targeted safety nets for the poor.

Public-sector wage bill cuts/freezes

Since 2010, reducing or freezing the salaries and number of public-sector workers have been among the measures commonly considered by the IMF and other international financial institutions to consolidate government budgets (Ortiz and Cummins 2019). The most direct impact of these measures has been on the capacity of governments to hire and retain the millions of front-line workers — teachers, nurses, health aides, social workers and doctors — to deliver education, health, childcare and other essential services to the population. To take one important example, ensuring the availability and quality of health care requires the creation of decent jobs in the health sector, which currently faces a global deficit of 18 million workers that is projected to increase further by 2030 (WHO 2017).

In 2020, IMF economists recommended measures to control or reduce the public-sector wage bill in many instances. In most cases, IMF staff made these recommendations in order to create fiscal savings. However, efforts to bolster health-care delivery and other essential services are highly contingent on the capacity of governments to attract and retain qualified staff in front-line public-sector jobs. In several African countries, the liberalization of private practice alongside the severe deterioration in the funding of the public health sector has led to the stagnation of already low wages for nurses and lower-level health personnel. Other problems behind the shortage of nurses and midwives that currently afflicts the public health sector include the long hours of work; heavy workloads; the lack of basic material for infection control and resulting health risks at work; and the lack of performance-based monetary incentives.

In 2020, the IMF recommended or supported the containment of the public-sector wage bill in 9/15 or 60 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 23/39 or 58.9 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries, 26/49 or 53.1 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries and 15/44 or 34.1 per cent of reports on low-income countries.

Here are some examples of IMF advice on wages.

-

Request for purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument for the Bahamas (report 20/191 ) : Absent additional measures, the fiscal balance is projected to reach the FRL target only in FY2022/23 and the debt ratio will remain above 50 percent of GDP (the Fiscal Responsibility Law target) beyond FY2024/25. Decisive measures are recommended to keep debt on a downward path, while carefully balancing the composition of spending to achieve inclusive growth and invest in natural disaster preparedness...Against this background, staff recommended to contain expenditure growth by further rationalizing the wage bill, advancing the pension reform, and accelerating SOEs reforms. -

Request for disbursement under the Rapid Credit Facility for Lesotho (report 20/228) :Staff and the authorities agree on the need to reduce the wage-to-GDP ratio over the medium term, which can be achieved through a combination of wage restraint, removing ghost workers, and reviewing the number of positions, without undermining service delivery . -

Third review under the Stand-By Arrangement and Arrangement under the Stand-By Credit Facility for Honduras (report 20/186): The consolidation will be supported by higher revenue—mainly 0.8 percent of GDP in terms of tax revenue from the recovery and 0.7 percent of GDP from policy measures under the program—and lower current spending by 0.6 percent of GDP—from the absence of electoral spending and wage containment, facilitated by the recently approved wage bargaining mechanism, which can limit wage increases to expected inflation.

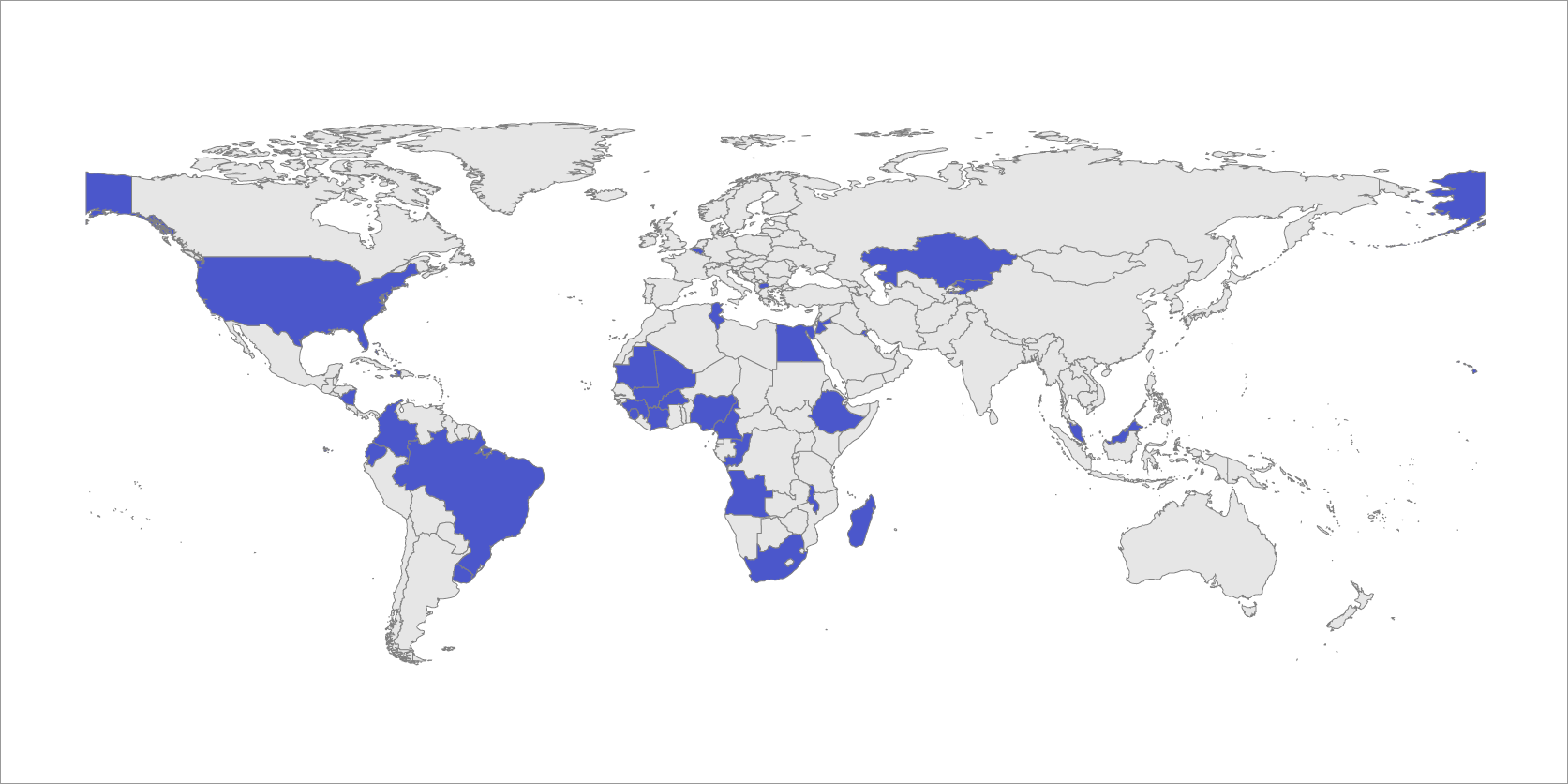

Figure 13 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended limiting or cutting the public-sector wage bill in 2020.

Figure 13: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to reduce the public wage bill in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Fees for public services

Dominant policy trends since the 1980s, in the context of recurrent crises, liberalization and public-sector retrenchment, have moved towards the commercialization of public social services, undermining previous progress towards universal access in many countries, raising out-of-pocket costs, particularly for the poor, and intensifying inequality and exclusion. Systems that are fragmented – with multiple providers, programmes and financing mechanisms aimed at different population groups – have shown limited potential for redistribution and have generally resulted in high costs, poor quality and limited access for the poor. By contrast, integrated systems of social service provision that are grounded in universal principles can be redistributive, act as powerful drivers of solidarity and social inclusion and improve the capabilities of the poor (UNRISD 2010).

To give one example – health services – the commercialization of health services has been more prevalent in lower- than in higher-income countries. Overall, in the health sector, the commercialization of services has been associated with worse access and inferior outcomes, and viewed as “an affliction of the poor” (Mackintosh and Koivusalo 2005). The motivations behind the introduction of user fees and charges and therefore the push towards the commercialization of services have included cost recovery; greater efficiency through competition among providers; and instilling in recipients a greater sense of value for the services obtained. In general, there has been a failure to achieve these aims due to flawed assumptions about how markets work. Nor have complementary targeted forms of assistance or exemption mechanisms, which are designed to improve the access of marginalized groups to services in the context of commercialized provision, been effective in increasing coverage due to supply constraints, inadequate resources, high administrative costs, leakages and stigma.

In order to create fiscal savings, the IMF recommended in some reports to reduce expenditure on the provision of some public services and increase the user fees or tariffs charged to users. Examples include increasing fees on:

-

public transport (for example in Italy: report 20/79; and in Angola: report 20/281); -

electricity (for example in Honduras: report 20/79; Jordan: report (20/101); and Ethiopia: report 20/29); -

health-care services (for example in Malaysia: report 20/57); and -

energy (for example in the Republic of Moldova: report 20/76; and Burkina Faso: report 20/76).

In 2020, 5/15 or 33.3 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 5/39 or 12.8 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries, 8/49 or 16.3 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries and 6/44 or 13.6 per cent of reports on low-income countries contained recommendations to reduce expenditure on the provision of some public services by increasing user fees (figure 14).

The following are examples of IMF advice on user fees for public services contained in reports in 2020.

-

Fourth review under the Extended Arrangement for Barbados (report 20/314) :Reform of State-owned Enterprises is essential to secure medium-term fiscal viability. We have developed a framework to restructure and transform our SOEs based on principles of retooling and empowering, retraining and enfranchising of Barbadians. We have conducted a comprehensive review of all state-owned entities, to identify potential for efficiency gains, cost recoveries, and enfranchisement through divestment of entities and/or activities. SOEs listed in the TMU have now all submitted standardized (according to international acceptable standards) quarterly financial reports. We have increased bus fares, adjusted water rates, and introduced a quarterly’s interim health levy, airline & travel development fee and a garbage and sewage contribution levy. -

Article IV Consultation and Request for Three-Year Arrangement under the Extended Credit Facility and an Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility for Ethiopia (report 20/29) :Improving expenditure efficiency by undertaking a review of explicit and implicit subsidies and rationalizing them, simultaneously with poverty-impact mitigation measures to be determined at that stage. Electricity tariffs should continue to be raised to eventually ensure cost recovery, in line with the reform schedule agreed under the World Bank DPF triggers. -

Third review under the Stand-By Arrangement and Arrangement under the Stand-By Credit Facility for Honduras (report 20/319) :Reforms in the electricity sector and renewed revenue mobilization efforts after the pandemic subsides will also increase fiscal space for much-needed investment and social spending. Renewed efforts in the electricity sector will put ENEE’s financial situation on a sustainable path. These include implementing the electricity sector law approved in 2014, continuing to strengthen the regulatory body and addressing governance issues both in the electricity sector and in ENEE, reducing electricity losses and energy purchase costs, keeping tariffs in line with costs.

Figure 14 shows the regional distribution of the recommendation to increase or impose fees on the provision of public services.

Figure 14: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to Increase Fees on Public Services in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020

Recommendations regarding pension reform and social security contributions

Pension systems, by their nature, require regular adjustments to adapt to societal developments, including demographic changes and labour market transformations, as well as to maintain actuarial and financial sustainability. This explains the need for minor or major legal and administrative reforms that preserve their balance and sustainability. Reforms of pension systems become more frequent as the demographic structure of a country becomes more mature, making such reforms more prominent in upper-middle-income and high-income countries.

However, sustainability is not the only criterion that social security systems (including pension schemes) need to comply with: the level of coverage of the population and the adequacy of benefits are other key dimensions, which are among the very objectives that pension systems were created to meet. The ILO Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) establishes core principles and minimum standards in terms of the design of benefits, financing and governance of social security systems, which become mandatory for ratifying countries. Higher-level Conventions that are specific to each of the branches of social security establish targets that are more ambitious than those of Convention No. 102, which has been ratified by 60 countries as of November 2021, including 33 of the countries whose cases were analysed in this report.

More recently, the Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202) defines a set of guarantees that should be extended to all persons and recommends that countries establish national strategies to universalize their social protection systems, including floors. Relevant tripartite instruments, especially the recently adopted Conclusions concerning the second recurrent discussion on social protection (social security) (ILO 2021c), have been adopted by governments, employers and workers at the International Labour Conference. Such instruments establish the importance of achieving universal social protection by on the one hand combining rights-based and adequately financed social security systems and on the other hand promoting decent work and formalization.

Social security reforms (including pension reforms) that aim to balance public finances but fail to take into consideration other key principles and minimum criteria – including adequacy of benefits, solidarity in financing and tripartite governance – do not adequately align with the normative criteria established by ILO constituents. This includes reforms that restrict coverage, sometimes by shifting from universal to targeted schemes, with the stated objective of “efficiency” in social spending. On the other hand, reforms that are based on actuarial evaluations, with due regard for the internationally recognized normative framework, and are legitimized by social dialogue that involves the key actors of the social security regime, are clearly necessary to keep social security regimes functioning for all.

Such reforms would combine measures that progressively adapt the parameters of contributory regimes according to demographic and social developments, in tandem with labour market policies that expand opportunities for decent work; reduce discrimination; foster the transition from informality to formality; extend the obligation to affiliate beyond the dependent worker group; and promote administrative reforms of social security schemes to facilitate affiliation, contribution payment, collection, inspection, investment of reserves and payment of benefits to newly insured groups. In an ILO multi-pillar model, contributory social insurance schemes (the “first pillar”) should be well coordinated with non-contributory universal pensions (the “zero pillar”) and a possible “second pillar” of contributory complementary pensions, whether employer-based or based on mechanisms such as individual savings accounts.

Public pension schemes that are based on solidarity and collective financing, in line with ILO social security standards, remain by far the most widespread pillar of old-age protection globally (ILO 2021a). Many countries are introducing parametric reforms to their contributory pension systems in order to adapt them to changing conditions and ensure their long-term sustainability. While important, these parametric reforms can only go so far in the face of macro phenomena such as wage suppression; frozen contribution rates; growing inequalities; and last but not least, the falling labour share of income.

During 2020, the IMF recommended or supported country proposals for pension reform either immediately or after the pandemic abates. Figure 10 shows that the IMF recommended that governments reform their pension systems in 13/15 or 86.7 per cent of high-income countries, 11/39 or 28.2 per cent of upper-middle-income countries, 11/49 or 22.4 per cent of lower-middle-income countries and 3/44 or 6.8 per cent of low-income countries in 2020.

More background information is needed to understand whether the recommendations made in 2020 are part of the expected efforts to adapt social security systems to societal developments, including population ageing, and whether additional recommendations are needed to improve not only the sustainability of the systems but also their coverage and the adequacy of their benefits. It is also worth noting that a number of countries that have adopted structural pension reforms (that is pension privatization) since the 1980s, in line with policy advice from the World Bank, have had to confront high (and often still rising) fiscal transition costs in cases where public pension schemes have been partially or totally replaced by individual accounts.

Some of the recommendations made by the IMF during 2020 are set out below.

-

Article IV consultation for Albania (report 20/29) :Staff also supported the development of a second pillar of the pension system, to strengthen the social safety net and deepen capital markets through new savings instruments. -

Article IV consultation for Brazil 2020 (report 20/311): Subnational pensions should be reformed in line with the new provisions for federal government employees. State and local governments were left out of the 2019 federal pension reform. Private sector estimates indicate the reform of subnational pension schemes could save up to 5 percent of GDP over 10 years. -

Seventh review under the Extended Fund Facility Arrangement for Georgia (report 20/322) :Despite the challenging environment, the authorities performed well under the EFF program. They implemented all structural benchmarks, including the adoption of a rule-based pension system, to contain long term fiscal risks and support inclusive growth. (…) In addition, with one of the highest population ageing rates, Georgia’s health and pension spending is expected to increase substantially in the medium-to-long term (albeit from currently low levels). The recent increase in basic pensions and newly instated pension indexation rule, much needed to protect elderly people’s real incomes and safeguard against ad-hoc discretionary increases, also adds to the pension bill. In order to maintain current net worth, fiscal adjustments will be needed through reducing spending and/or increasing revenues. The authorities’ medium-term fiscal strategy proposes reforms to address these issues. -

Third review under the Stand-By Arrangement for Honduras (report 20/319) :The pension funds have to issue investment policies that aim at aligning the maturity of their assets and liabilities and optimizing its risk-return strategy. -

Article IV consultation for Italy (report 20/79) :Consolidation should be underpinned by pro-growth and inclusive measures, including lower tax rates on labor, base broadening, and lower current spending (especially on the pension bill). (…) Staff advises preserving the indexation of retirement age to life expectancy, ensuring actuarial fairness including for options to retire early (i.e., closely linking lifetime benefits with lifetime contributions), and adjusting pension parameters to secure affordability. -

Article IV consultation for North Macedonia (report 20/24) :Pensions are in general more generous than in peer countries. Full implementation of the CPI indexation of pension benefits approved in 2019 would save about 0.6 percent of GDP by 2022, compared to staff’s baseline which assumes that pension benefits will increase by CPI inflation plus a third of nominal GDP growth. -

Article IV consultation for Panama (report 20/124) :The pension system needs to be strengthened. Faced with slowing population growth, the authorities need to gradually align pension contributions with expected payouts, to avoid creating an undue burden to the public finances in the long run.

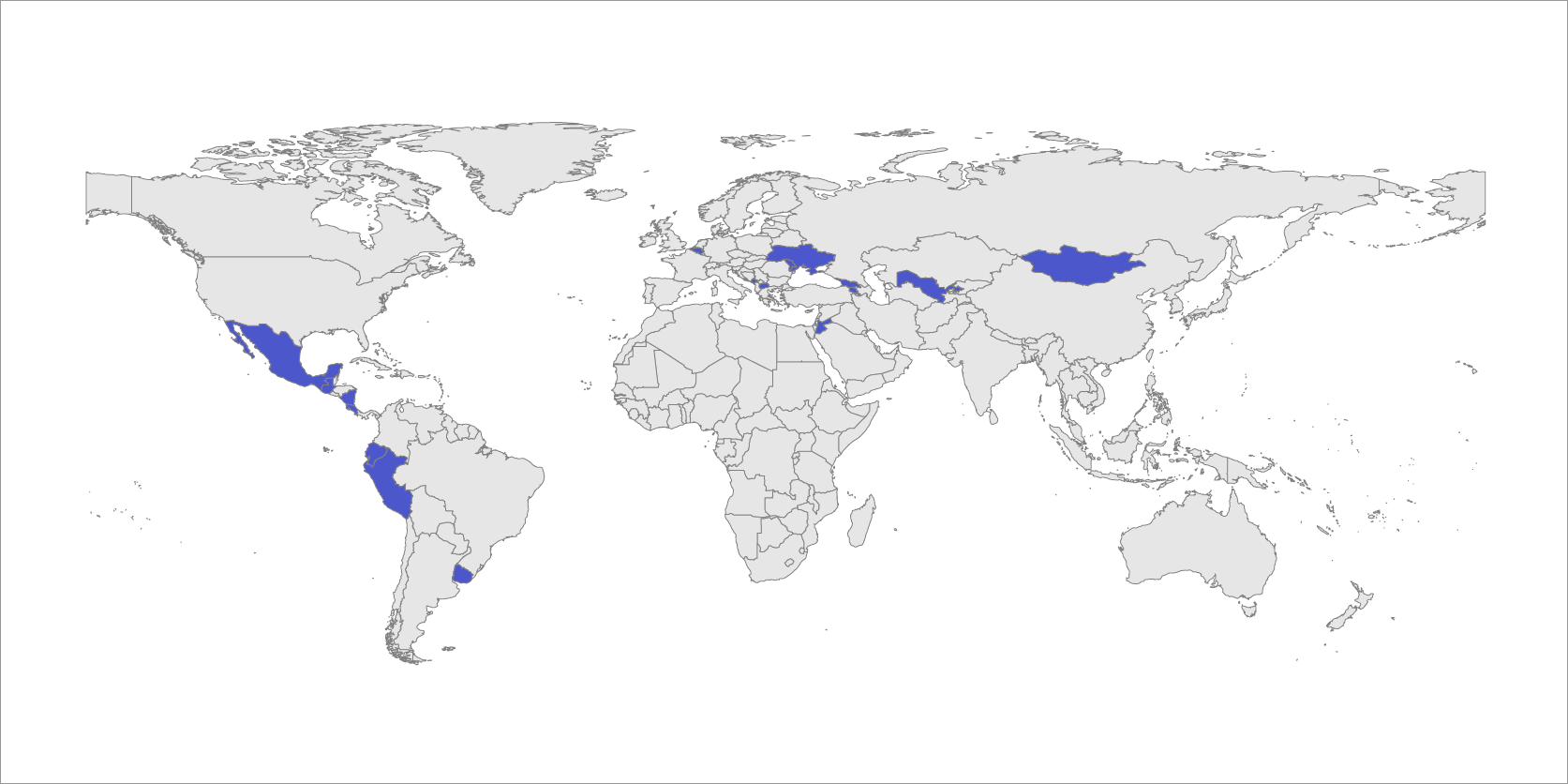

Figure 15 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended the reform of pension systems in 2020.

Figure 15: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to reform pension systems in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Social security contributions

In its 2020 reports, IMF staff generally supported the relief provided by governments to employers and individuals with regard to their contributions to social security funds, supporting the deferral or temporary suspension of social security contributions made by firms in 1 lower-middle-income country report, 6 upper-middle-income country reports and 1 high-income country report. In 3 country reports, the IMF also recommended or supported the reduction of social security contributions in order to encourage formalization in the labour market. Despite the good intentions underlying those measures, it is important to keep in mind that social security contributions are earmarked to finance social security benefits and therefore compel social security institutions to consume reserves beyond the usual emergency or fluctuation reserves. If these buffers, made up of funds that belong to the members of social insurance schemes, are not rebuilt to compensate any losses caused by a political decision, future benefits can be put in peril. This is valid not only for the reserves that back up collectively financed schemes, but also for savings that are withdrawn from individual accounts due to the absence or insufficiency of unemployment benefits.7

In addition, it is important to add that such temporary decreases of social contributions should not be taken as a precedent to arbitrarily reduce social security contributions in the future to accommodate other political or fiscal pressures. It is worth recalling that Convention No.102 requests countries to run and present actuarial projections whenever a change of benefit and contribution rules is proposed, thereby seeking to ensure the sustainability of the respective schemes.

However, the IMF generally placed emphasis on raising social security contributions. In 2020, 2/15 or 13.3 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 2/39 or 5.1 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries and 5/49 or 10.2 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries contained recommendations to increase contributions to the social security fund. These recommendations to increase contributions were made with a view to increasing the sustainability of social security funds and reducing the contributions of the government to these funds.

It is important to note that social security contributions are different from taxes, since they create the right to future benefits. Also, there is no empirical evidence to show that social security contributions are the main explanation for labour market informality, given that informality is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon that has several drivers. Furthermore, social security contributions are the single most important source of financing for social protection throughout the world. Recent ILO estimates show that developing countries would on average need to invest 3.8 per cent of their GDP per year in order to close the financing gap for a universal social protection floor for all, including health care, already taking into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Social security contributions could be the source of an estimated 1.2 per cent of GDP – almost one third of the resources needed (ILO 2020b).

Table 5 summarizes the IMF recommendations on changing social security contributions. Figure 16 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended or supported government measures related to modifying the level of social security contributions in 2020.

Table 5: Number of reports with recommended changes to social security contributions by country income groups in 2020

|

Recommendation |

Lower-middle-income countries |

Upper-middle-income countries |

High-income countries |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Increase |

5 |

2 |

2 |

9 |

|

Deferral |

1 |

6 |

1 |

8 |

|

Decrease |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

In section IV on pensions, a quote from the Article IV consultation for Italy (report 20/79) already contained a recommendation to reduce tax rates on labour as a “growth-friendly measure”. A second example is cited below from a report on Jordan that includes support for measures relating to social security contributions, as well as other related topics.

-

Article IV consultation and request for an Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility for Jordan (report 20/101): In addition, pro-employment reforms are critical for inclusive growth and stability. Much has already been done. The authorities have amended the Social Security law, which now allows for: (i) a temporary reduction in contribution rates for small startups employing young workers; (ii) cash support for nurseries in areas with low female labor force participation; (iii) access to individual unemployment insurance savings to support higher education and medical expenses; and (iv) parametric reforms for social security (increasing the early-retirement age and the associated deduction rate, and allowing part-time workers to contribute to the scheme). The authorities have also recently approved a series of incentives to directly boost job creation for targeted groups (youth and women) through conditional direct cash support to businesses.

Figure 16: Regional distribution of IMF recommendations to modify social security systems in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Labour market flexibilization reforms

In many cases, the IMF also recommended or supported the implementation of labour market reforms, or their continuation, to make them “more flexible”. This was the case in 9/15 or 60 per cent of reports on high-income countries, 15/39 or 38.5 per cent of reports on upper-middle-income countries, 7/49 or 14.3 per cent of reports on lower-middle-income countries and 1/44 or 2.3 per cent of reports on low-income countries.

Labour market reforms that make the employment relationship “more flexible” generally include relaxing dismissal regulations; restraining minimum wages; limiting salary adjustments; decentralizing collective bargaining; and making it easier to hire workers on temporary and non-standard contracts. Such reforms are supposed to increase competitiveness and support businesses. However, there is limited evidence to show that labour market flexibilization generates jobs, particularly during recessions, while women workers are particularly hard hit by such measures. In fact, evidence from 110 countries suggests that no direct link can be found between the “stringency of employment protection legislation” and the aggregate employment rate, and that its deregulation in a context of economic contraction is likely to generate “precarization” and vulnerable employment, and to depress incomes, and therefore aggregate demand, ultimately hindering crisis recovery efforts (Adascalitei and Pignatti Morano 2016; ILO 2016).

Instead, a virtuous combination of factors that includes a number of labour market institutions and policies, including well-designed employment protection legislation, can create the envisaged positive effects, while factors beyond the labour market often strongly influence the possibility of creating new employment opportunities. It is concerning that many countries have been experiencing persistent wage stagnation, since wage increases have not kept pace with productivity, while wage inequality is also increasing steeply (G20–L20 2018). Not surprisingly, a Global Poll by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) (2018) shows that 84 per cent of the world’s workers say that the minimum wage is not enough to live on.

With regard to labour market flexibilization reforms, it is encouraging that the IMF (2019) has identified the need to promote consultations with trade unions and civil society organizations in its new Social Spending Strategy. The ILO promotes “decent work” for all, a concept that comprises, in its four dimensions, compliance with (1) fundamental norms and rights at work; (2) productive and adequately paid decent employment; (3) social protection; and (4) tripartite social dialogue. Importantly, the ILO’s first role since its inception in 1919 was to develop a framework of international norms that establishes minimum labour and social security standards, based on the diagnostic that the absence of such standards contributed to the high levels of poverty and social distress that set the stage for the First World War.

Two fundamental Conventions related to the freedom of association, the right to organize and to promote collective negotiations are the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No.87) and the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No.98), which have been ratified by 157 and 162 countries, respectively. Among the countries included in the present report that signed agreements with the IMF in 2020, 90 had ratified Convention No. 87 and 96 had ratified Convention No. 98. Another very relevant “governance” Convention refers to the commitment of countries to discuss with the social partners the developments and modifications of all policies related to ILO matters, namely Tripartite Consultation (International Labour Standards) Convention, 1976 (No.144). To date, this Convention has been ratified by 156 countries, 86 of them among the signatories of agreements with the IMF in 2020. The Employment Policy Convention, 1964 (No.122) is another of the eight “governance” Conventions and refers to the commitment of the 115 ratifying countries (58 of them mentioned in this study) to pursue “full, productive and freely chosen employment” for all (Article 1). Countries that have ratified these Conventions (and others, such as those on work conditions) should ensure respect for these principles in their public policies when negotiating agreements with other international organizations, including the IMF.

Some examples of IMF advice regarding the labour market made in reports in 2020 are set out below.

-

2020 Article IV consultation for Nepal (report 20/96): Amendments to the Labor Bill and Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act (FITTA) are needed which enhance labor and product-market flexibility. -

2020 Article IV consultation for Italy (report 20/79): Further liberalize product and service markets; decentralize wage bargaining to realign wages with labor productivity at the firm level; enhance public sector efficiency; and deploy the new insolvency code. -

2020 Article IV consultation for North Macedonia (report 20/24): Reforms to address key labor market and institutional weaknesses will help lift medium-term growth and speed up income convergence (with the EU). (…) This should be complemented by efforts to build physical capital given infrastructure gaps and to boost human capital to address skills shortages and mismatches, including through vocational education and training and more use of skill-enhancing active labor market policies. Reforms to tackle informality would help improve the business climate and protect workers, with potential large revenue gains. -

2020 Article IV consultation for Brazil (report 20/311): Further changes in labor market regulation are currently being considered to reduce labor costs for the private sector and improve the ease of doing business.

Figure 17 shows the countries in which the IMF recommended the implementation of labour flexibilization reforms.

Figure 17: Regional distribution of IMF recommendation to implement labour flexibilization reforms in 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IMF country reports in 2020.

Recommendations regarding government revenues