Investing more in universal social protection

Filling the financing gap through domestic resource mobilization and international support and coordination

Abstract

Large and persistent gaps in social protection coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy are linked to many barriers, including high levels of informality, institutional fragmentation of the social protection system and significant financing gaps for social protection in a context of limited fiscal space. The latter have been further exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19. Against this background, this paper discusses the magnitude and urgency of the challenge of filling social protection financing gaps and the options for achieving this. Options exist even in low-income countries, including by broadening the tax base; tackling tax evasion and building fair and progressive tax systems together with a sustainable macroeconomic framework; duly collecting social security contributions and tackling non-payment or the avoidance of social security contributions; reprioritizing and reallocating public expenditure; and eliminating corruption and illicit financial flows. National social protection systems should be primarily financed from domestic resources; however, for countries with limited domestic fiscal capacities or countries facing increased needs due to crises, natural disasters or climate change, international financial resources, in combination with technical assistance, could complement and support domestic resource mobilization for social protection. Furthermore, more dialogue and coherence need to be achieved between international financial and development institutions to avoid contradictory policy advice on the level and nature of investment in social protection. Finally, international cooperation, such as on tax matters or debt restructuring, is needed to create an environment that facilitates domestic resource mobilization.

JEL classification: I3, H3, H53, H55

Key words: social protection, social security systems, social protection floors, social security contributions, public expenditure, fiscal space, social protection financing, solidarity, domestic resource mobilization, official development assistance (ODA), developing countries, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Key points

-

Today more than 4 billion people are still excluded from social protection. Large and persistent gaps in social protection coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy are linked to many barriers, including high (and sometimes increasing) levels of informality, institutional fragmentation of the social protection system and significant financing gaps for social protection in a context of limited fiscal space. The latter have been further exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased the urgent demand for social protection to protect individuals’ health and income and at the same time has decreased national resources for social protection by diminishing tax and contributory revenue.

-

To realize the right to social security for all by 2030, more investment in social protection is indispensable. Options for sustainably increasing fiscal space for social protection exist even in low-income countries, including by broadening the tax base; tackling tax evasion and building fair and progressive tax systems together with a sustainable macroeconomic framework; duly collecting social security contributions and tackling the avoidance of social security contributions; reprioritizing and reallocating expenditure; and eliminating corruption and illicit financial flows.

-

National social protection systems should be primarily financed from domestic resources, which need to be gradually increased in line with the economic and fiscal capacities of the country and based on national priorities. However, for countries with limited domestic fiscal capacities to invest in social protection or countries facing increased needs due to crises, natural disasters or climate change, international financial resources, in combination with technical assistance, could complement and support domestic resource mobilization for social protection.

-

In additional to technical and financial assistance at the country level, more dialogue and coherence needs to be achieved between international financial and development institutions to avoid contradictory policy advice on the level and nature of investment in social protection. Moreover, international cooperation, such as on tax matters or debt restructuring, is needed to create an environment that facilitates domestic resource mobilization.

Introduction

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic threw the world into turmoil, it was clear that the global community was failing to live up to the commitments it had made in the wake of the last global catastrophe, namely the 2008 global financial crisis. This commitment took concrete shape in the Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202) and was further endorsed by the transformative 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Yet, progress towards building national social protection floors and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on social protection (SDG target 1.3) and universal health coverage (SDG target 3.8) has lagged. Large coverage gaps persist, which deny people’s enjoyment of the right to social security1 that is firmly enshrined in several human rights instruments. As of 2020, 53.1 per cent of the world’s population had no access to social protection benefits at all and 70.4 per cent of the working-age population were not legally covered by comprehensive social security systems (ILO 2021i). At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a massive loss of jobs, amounting to the equivalent of 255 million full-time jobs in 2020 alone

These large and persistent gaps in social protection coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy are linked to barriers that require strong political will to be overcome. These include high (and sometimes increasing) levels of informality, institutional fragmentation of the social protection system and significant financing gaps for social protection in a context of limited fiscal space. These gaps have been further exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased the urgent demand for social protection to guarantee access to required health services, compensate for the loss of income due to lockdowns, physical distancing measures and job losses, while at the same time decreasing national resources for social protection by diminishing tax and contributory revenue.

Whereas in countries with more developed social protection systems pre-existing statutory schemes automatically fulfilled their protective function for large parts of the population, many countries had to urgently fill protection gaps by introducing new measures or extending the coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy of existing social protection schemes

Evidently, mere stopgap measures are not enough to protect people in the current crisis, to support swift and inclusive recovery and to build resilient systems for the future. Whereas these crisis measures have thrown a lifeline to many vulnerable workers and families throughout the world, there is the risk of a “cliff fall” scenario, whereby emergency social protection support ends prematurely and abruptly before the crisis and its material consequences for people have ended and before the economy has fully recovered, leaving people once again without protection. Rather, countries can use the current political momentum and recognition of the importance of social protection to build on or transform such temporary relief measures into rights-based and robust social protection systems, including floors,2 and to ring-fence the resources required to ensure their adequate and sustainable financing. In doing so, they would guarantee access to essential health care and income security over the life cycle – the two main dimensions of social protection – and create and safeguard the necessary fiscal space for social protection

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown once more that social protection is an indispensable tool to protect individuals’ health, incomes and jobs, and productive assets in the case of a shock. Social protection is key to preventing and reducing poverty in all its forms, vulnerability and social exclusion (SDG 1). The case for social protection becomes even more compelling when considering that it is an investment in human development; it plays a pivotal role in promoting social and economic development, more inclusive societies and more effective investments in human capital and human capabilities

Furthermore, social protection stabilizes aggregate demand during economic downturns or crises and supports measures to protect jobs and the productive assets of the self-employed and enterprises and to ensure business stability, as we are currently witnessing. It thereby fosters the resilience of societies to bounce back more quickly after a crisis. In close coordination with other policies, such as economic or employment policies, social protection can contribute to facilitating the structural transformation of economies and societies, notably the formalization of the labour market

Box

Over the past decades, a solid evidence base has been developed that demonstrates the positive impact of social protection on reducing poverty and inequality and promoting positive outcomes related to nutrition, education, health, labour market participation, enterprise performance and social cohesion

More recently, additional studies have investigated the magnitude of returns on investment and multiplier effects, assessing different types of outcomes and time frames and using different methods. One such example is the local economy-wide impact evaluation model. Model estimates for cash transfer programmes in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe showed that for every currency unit invested, a higher amount was created in the local economy – ranging from 1.34 Kenya shillings (K Sh) for every K Sh1 invested in Kenya to as high as 2.52 Ethiopian birr (Br) for every Br1 invested in Ethiopia

Based on dynamic microsimulation models, another strand of the literature investigated the returns on social protection investment in terms of income, child health and education. A study conducted in Cambodia found positive effects on household consumption, health, education and labour market participation. After 12 years, there were positive returns on investment; that is, the difference in total household consumption between policy and baseline scenarios exceeded the investment

Finally, based on a structural model and simulations, research in Brazil investigated the multiplier effects of different components of federal government expenditure on gross domestic product (GDP). Social benefits and public investments created the largest multiplier effects, with an accumulated effect of social benefits on GDP of 2.9 after 25 months

Barriers to effectively extending social protection are manifold and depend on specific country contexts. Political economy factors, such as the capture of decision-making by economic elites, are often a major obstacle. But also, even when governments have the political will to achieve SDG 1.3 and SDG 3.8, the lack of resources to design, finance and implement rights-based social protection systems remains a crucial challenge. Nonetheless, many low- and middle-income countries, sometimes with the support of development partners, have come a long way in strengthening their social protection systems, including social protection floors that guarantee at least a basic level of social security to all

Despite national and international efforts to strengthen and scale up social protection systems and increase domestic resource mobilization, investments in social protection remain insufficient in most cases. In addition, there is a need to protect social security financing against disproportionate austerity measures that constrain public social expenditure, weaken aggregate demand and make crises worse, as happened in many developing countries after the global financial crisis in 2008

Considering persistent social protection coverage and financing gaps, the international community seems to agree that (see also

-

more investment in social protection is needed to close the financing gap, which should come primarily from innovative and diversified sources of domestic financing; these resources need to be gradually increased in line with the economic and fiscal capacities of the country and based on national priorities;

-

for countries with limited fiscal capacities to invest in social protection or facing increased needs due to crises (such as in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic), natural disasters or climate change, additional international financial resources in combination with technical assistance could temporarily complement national resources and support domestic resource mobilization for sustainable financing of social protection; and

-

national policymakers, social partners and bilateral and multilateral partners should align and increase synergies towards extending the fiscal space for social protection and explore ways (such as through an international financing mechanism or intensified cooperation on tax matters or debt restructuring) to create an environment that facilitates domestic resource mobilization.

Against this background, this paper discusses the magnitude and urgency of the challenge in terms of financing social protection and options to fill existing gaps. It first summarizes the coverage and financing challenge faced in particular by low- and middle-income countries, already taking into account the preliminary effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The second part of the paper discusses options that countries have at their disposal to increase fiscal space for social protection at the national level. It provides an initial review of how the international community could support and complement national efforts following a coordinated, sustainable and country-owned process. This includes the provision of both technical support to increase domestic resource mobilization and additional financial assistance from international sources to fill financing gaps, notably in countries with limited domestic fiscal capacities and other countries that face exceptional challenges.

A complementary paper on investing better in social protection outlines the guidance that international social security standards provide to inform social protection policy and financing decisions; when systematically applied by all actors, such standards could ensure that the mobilization and allocation of resources for social protection are well coordinated at all levels, thereby accelerating progress towards achieving universal social protection by 2030

Box

To accelerate the implementation of the SDGs and build a better world for the future generations, the United Nations Secretary-General’s report

The Secretary-General also launched the Global Accelerator for Jobs and Social Protection at a high-level event on Jobs and Social Protection that he convened with the Prime Minister of Jamaica and the Director-General of the ILO on 28 September 2021. The Global Accelerator for Jobs and Social Protection aims to support a recovery from the crisis that is fast, inclusive, sustainable and resilient. It will promote and support additional investments in low- and middle-income countries, through domestic resource mobilization and temporary international financial support to complement national efforts aimed at job creation, social protection system-building, green transition and formalization. It will be backed by more effective and enhanced multilateral cooperation.

The Accelerator is organized around three complementary and mutually supportive pillars for accelerating action:

-

pillar 1: to bring greater policy coherence at the national level through integrated and costed national policies and strategies by combining job creation, universal social protection and just transition; -

pillar 2: to build a comprehensive financial architecture based on domestic resources and international finances, as well as measures to leverage investment from the private sector; and -

pillar 3: to enhance multilateral cooperation by strengthening engagement and collaboration among multilateral institutions, bilateral donor agencies, developing country governments, social partners, philanthropic foundations and experts.

A transversal Technical Support Facility will support all three pillars and seek to align financial and technical assistance for a human centred recovery and sustainable development.

Box

In this Resolution and conclusions, the ILO’s 187 Member States, represented by governments and by employers’ and workers’ organizations, reaffirm the full relevance of the guiding principles contained in Recommendation No. 202 and the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) and the need to implement them in a holistic manner, since neglecting one of them risks jeopardizing the solidity of social protection systems. They request the ILO to take into consideration the principles laid out in relevant social security standards when supporting Member States in ensuring sustainable and adequate financing for social protection policies. They also request the ILO to use and promote the principles established in ILO social security standards when engaging with IFIs (including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)) on options to increase and secure adequate and sustainable financing for social protection.

Financing gaps to achieve SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 during COVID-19 and beyond

Social security, an adequate standard of living and health are human rights, but a reality for far too few people. The COVID-19 pandemic has once again demonstrated the dramatic consequences of these unacceptably high coverage gaps, which lead to suffering, destitution and even death, exacerbate economic and social inequalities, and undermine social cohesion in many countries. At the start of the pandemic, only 46.9 per cent of the global population were effectively covered by at least one social protection benefit (such as child or family benefits, maternity benefits, unemployment benefits, employment injury benefits, disability benefits, old-age pensions, survivors’ pensions or social assistance), while the remaining population, as many as 4.1 billion people, were completely unprotected when the crisis hit.

These average global coverage rates mask extensive regional disparities, ranging from only 17.4 per cent of people in Africa having access to some form of social protection to 83.9 per cent of people in the Europe and Central Asia region

These coverage gaps are linked to significant financing gaps that have been further exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to provide an overview of the additional resources needed in low- and middle-income countries for achieving SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8,

2.1 Global estimates of financing gaps to achieve SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 in 2020

Table

|

Population (millions) |

Gap in achieving SDG target 1.3 (billions of US$) |

Gap in achieving SDG target 1.3 (percentage of GDP) |

Gap in achieving SDG target 3.8 (billions of US$) |

Gap in achieving SDG target 3.8 (percentage of GDP) |

Total gap (billions of US$) |

Total gap (percentage of GDP) |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

All low- and middle-income countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low-income countries |

711.2 |

36.2 |

7.4 |

41.8 |

8.5 |

77.9 |

15.9 |

|

Lower-middle-income countries |

3 105.3 |

173.8 |

2.4 |

189.1 |

2.6 |

362.9 |

5.1 |

|

Upper-middle-income countries |

2 706.2 |

497.4 |

2.1 |

253.4 |

1.1 |

750.8 |

3.1 |

|

|

|||||||

|

Arab States |

110.3 |

15.1 |

4.5 |

10.2 |

3.0 |

25.2 |

7.5 |

|

Central and Western Asia |

212.6 |

86.6 |

7.9 |

15.2 |

1.4 |

101.8 |

9.3 |

|

Eastern Asia |

1 427.8 |

58.1 |

0.4 |

132.9 |

0.9 |

190.9 |

1.3 |

|

Eastern Europe |

227.1 |

32.8 |

1.6 |

21.8 |

1.1 |

54.6 |

2.7 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

619.1 |

272.1 |

6.1 |

61.1 |

1.4 |

333.2 |

7.5 |

|

Northern Africa |

245.5 |

31.5 |

4.7 |

24.1 |

3.6 |

55.6 |

8.3 |

|

Northern, Southern and Western Europe |

19.7 |

5.0 |

5.7 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

6.9 |

7.8 |

|

Oceania |

11.2 |

1.5 |

4.5 |

0.9 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

7.2 |

|

South-East Asia |

662.6 |

48.2 |

1.8 |

46.3 |

1.7 |

94.5 |

3.5 |

|

Southern Asia |

1 897.6 |

94.8 |

2.3 |

94.8 |

2.3 |

189.6 |

4.6 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

1 089.2 |

61.8 |

3.7 |

75.1 |

4.5 |

136.9 |

8.2 |

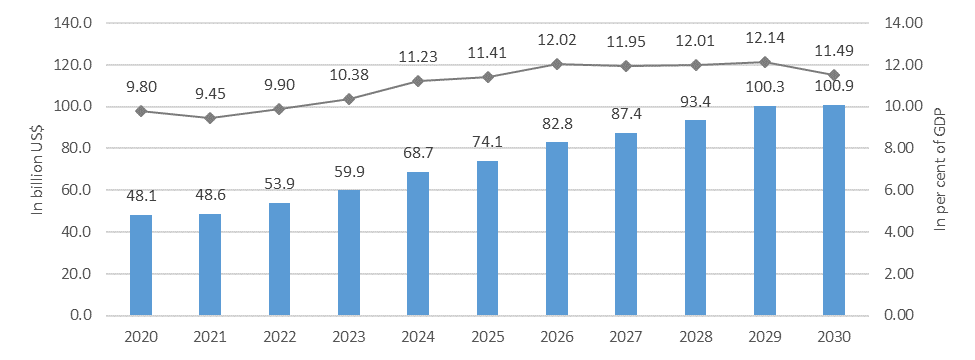

Even if low- and middle-income countries were able to mobilize the necessary resources to cover the financing gap, SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 could not be achieved immediately. Building social protection systems takes time, as it encompasses the development and adoption of national social protection strategies, the design of social protection schemes, the preparation and adoption of legal frameworks, the implementation of the schemes and monitoring progress, all based on tripartite social dialogue. It may also require the creation of institutions at the national and subnational levels. The study therefore assumes that financing gaps will be progressively filled over the 11-year period from 2020 to 2030, which is in line with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to achieve SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 by 2030. The financing needs to progressively achieve SDGs 1.3 and 3.8 by 2030 in low-income countries are illustrated in

Figure

Several other studies have assessed the (additional) costs of achieving the SDGs or different sets of goals, as well as the costs of closing social protection gaps, taking different approaches and perspectives. A detailed comparison of commonalities and differences is beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, what has become clear is that all these studies show that achieving the SDGs is affordable from a global point of view, yet exceeds the present economic capacities of low-income countries. For instance, based on IMF and World Bank research and International Centre for Tax and Development data,

The Social Protection Floor Index, conceptually based on Recommendation No. 202, provides an indication of the minimum resources that a country would need to invest or reallocate to close existing income and/or health protection gaps. Using the international poverty line of $1.9 in 2011 purchasing power parity (PPP) as the minimum level of income, the 25 low-income countries included in the study would have to invest on average additional 13.0 per cent of their GDP to close social protection gaps in 2018

Taking a broader perspective and including the achievement of more SDGs,

2.2 Developing and costing a shared national vision of social protection

The global and regional ILO estimates presented above are based on calculating the costs and remaining gaps of introducing a set of universal benefits that cover childhood, maternity, disability, old age and health – that is, all the components of social protection floors except for unemployment and sickness benefits. This benefit package was used to ensure comparability across countries and provides an overview of the approximate resource needs to achieve SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8. However, countries may choose other ways of achieving their nationally defined social protection floor. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, many countries have indeed prioritized access to health care (182 measures were reported in 84 countries as of 10 May 2021; see

Hence, these global and regional estimates cannot replace detailed costing studies of national social protection floors that are in line with a shared national vision of social protection, based on an in-depth assessment of the current state in a country and defined through effective tripartite social dialogue. This can be achieved through a so-called assessment-based national dialogue (ABND) (see

Such a dialogue is not only essential to identify policy gaps, reach agreement on priority policy options and cost them, but is also essential to devise and discuss possible financing options (see next section). Furthermore, it is essential that the results of national dialogues on social protection (and, if applicable, national social protection policies and strategies) are reflected in countries’ national development plans, integrated national financing frameworks

Box

Based on the experience of conducting ABNDs in 14 countries in Africa and Asia, the ILO prepared a global guide

An ABND provides a sound basis for identifying and costing policy scenarios based on national dialogue, as well as for discussing the creation of fiscal space by bringing all stakeholders to the table. Its success hinges on the participation of all stakeholders from the outset, including line ministries (finance and planning, health, labour, social affairs and so on), social security institutions and social protection programmes, local government bodies, employers’ and workers’ organizations, civil society organizations, academics, development partners or IFIs.

Timor-Leste, for instance, conducted such an ABND between 2016 and 2018. Its explicit goal was to inform its national social protection strategy. Throughout the process, representatives of the institutions listed above and many more were involved. Such an ABND comprises three steps, as described below.

(1)

(2)

(3)

Finally, it is necessary to follow up the implementation of the national social protection strategy and progress made in domestic resource mobilization for social protection. Mozambique, for instance, has been monitoring fiscal space for social protection for several years now and has demonstrated steady progress (see

Box

The Social Action Budget Brief in Mozambique is a joint initiative by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and ILO that aims to promote national debate around domestic fiscal space dedicated to basic (non-contributory) social protection in Mozambique. Since its first edition in 2013, it has been launched every year at a dedicated event during a Social Protection Week attended by representatives of the Ministries of Gender, Children and Social Action, Health, Education and Human Development, Economy and Finance, as well as by representatives of the Parliament, workers’ organizations, political parties, academia, journalists and international development partners. It is disseminated nationwide with the support of civil society organizations.

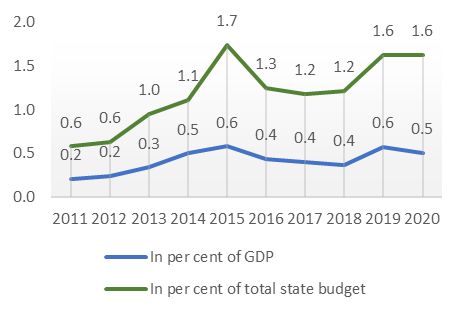

The Social Action Budget Brief monitors the budget allocation to social protection and financing sources, points out trends, reviews them in relation to the strategic objectives defined in the country’s National Basic Social Security Strategy (ENSSB) and provides key recommendations. In 2020, for example, 0.5 per cent of GDP or 1.6 per cent of the total state budget was allocated to social protection programmes, showing a positive trend over the past ten years (see

Between 2011 and 2020, the coverage of INAS programmes increased from 287,000 households to 608,724 households (see

The Social Action Budget Brief has been an effective tool to promote debate around the fiscal envelope dedicated to social protection, monitor progress and advocate for an expanded fiscal space for the sector. It also provides the basis for an evidence-based discussion with representatives of the Ministry of Finance and is an effective way to promote active engagement of employers’ and workers’ as well as civil society organizations during the preparation of the National Budget Law, as well as to track political commitments on social protection.

|

Figure |

Figure |

|

|

|

Enhancing domestic resource mobilization for social protection

This section discusses options to meet the financing needs identified at country level through domestic resource mobilization, with a view to securing “with due regard for the objectives of social justice and equity, a solid and sustainable economic, fiscal and financial base for the extension and operation of universal social protection systems over the medium to long term, without compromising the adequacy and coverage of benefits”

This shows that options to increase fiscal space, which is defined by the ILO, UNICEF and UN Women as “the resources available as a result of the active exploration and utilization of all possible revenue sources by a government”

Broadly, countries can consider eight different strategies for creating fiscal space for social protection

-

expanding social security coverage and contributory revenues;

-

increasing tax revenues;5

-

reallocating public expenditures and increasing the effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of policies;

-

eliminating illicit financial flows;

-

using fiscal and central bank foreign exchange reserves;

-

managing debt: borrowing or restructuring sovereign debt;

-

adopting a more accommodating macroeconomic framework; and

-

increasing official development assistance (ODA) and transfers.

For a comprehensive description and country examples, readers may wish to refer to

3.1 Increasing tax revenues and expanding coverage and revenues of contributory social security

Social protection systems are typically organized through a combination of tax-financed non-contributory schemes and social insurance schemes. It is estimated that contributory schemes finance more than 70 per cent of the social protection expenditure in low- and middle-income countries.

Increasing tax revenues is one of the options used to increase domestic resources for social protection

There are other ways to increase tax revenues. The Plurinational State of Bolivia, Botswana, Mongolia and Zambia have introduced taxes on their natural resources to finance their social protection programmes

Social security contributions, in turn, are usually funded by employers’ and workers’ contributions, which should be fairly divided between employers and workers. To strengthen the contribution base, countries need to increase the legal and effective coverage of existing schemes. First, countries can extent the legal coverage of existing schemes or create new schemes for previously uncovered groups with contributory capacity, such as workers in the informal economy; workers in small and medium-sized enterprises; domestic, construction or agriculture workers; or self-employed workers

Second, depending on the national context, different options to increase effective coverage through administrative, financial or institutional measures are possible

Social security contributions currently amount to 0.4 per cent of GDP in low-income countries, 2.5 per cent of GDP in lower-middle-income countries and 5.8 per cent of GDP in upper-middle-income countries, with an average of 5.1 per cent of GDP across all low- and middle-income countries

Countries that do not yet have contributory social protection systems in place or whose systems provide only protection for a limited number of risks should prioritize the development of such schemes to cover workers in formal sector enterprises; countries that have developed comprehensive contributory schemes for the formal sector should prioritize both their implementation through greater compliance with the social security law and their progressive extension to workers in all forms of employment (such as part-time workers, self-employed workers, domestic workers, informal economy workers and enterprises). Contributory schemes are usually self-financed from workers and employers’ contributions and as such do not put any strain on governments’ budgets.

Both options – increasing tax revenues and increasing social security contributions – require strong governance, administration, accountability and compliance mechanisms that work effectively and efficiently and are transparent. This ensures sound financial management, enforces compliance and prevents corruption and fraud, while also ensuring that the distribution of benefits is fair and efficient. In addition, extending the tax and contribution base also necessitates an integrated approach of social, economic and employment policies that work together to facilitate the transition of workers and enterprises to the formal economy, in line with the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204)

Furthermore, minimum wage policies and measures to boost productivity can help to ensure that salaried workers and the self-employed have adequate resources to live on and can contribute their share of contributions to social security. A “race to the bottom” may otherwise lead to a situation in which workers and employers resist the creation or further development of the national social protection system because they cannot afford paying their shares of social security contributions. Similarly, governments may be hesitant to expand social protection coverage for fear that it may disincentivize foreign investors. Trade agreements between countries and contractual agreements between buyers and suppliers in global and national supply chains can contribute to increasing both the political will, tripartite support and financial feasibility of introducing new social protection schemes.

Box

The Simples scheme is a Monotax (simplified tax collection/payment) mechanism for small contributors in Brazil, which unifies several taxes and contributions in a unique payment. Micro-entrepreneurs who join the scheme, as well as their employees, are automatically entitled to the benefits of the contributory social security system. It has proven to be an effective tool to formalize micro and small enterprises and to extend social security coverage to self-employed workers. Between 2008, when individual company owners were included, and 2016, the number of total registered firms covered by the scheme increased from about 3 million to about 12 million. The process works in a simple way. The Simples scheme divides companies into three levels according to their size. Individual micro company owners (smallest category, with one employee) pay a fixed monthly contribution. Micro companies (intermediate category) and small companies (larger category) pay progressive contribution percentages based on their classification. Simples contributions are collected by the central fiscal administration and the share corresponding to social security payments is transferred to the Social Security Institute to finance social security. Other countries in Latin America such as Argentina, Ecuador and Uruguay have already successfully implemented similar schemes.

3.2 Reallocating public expenditure and increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of social protection systems

The reallocation of public expenditure is another option that is commonly used in many countries. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, for example, Albania reallocated 2 billion leks (about US$19 million) of defence spending towards humanitarian relief for the most vulnerable. Similar examples of reallocating public expenditures to social protection can be found in Belize, Cabo Verde, the Dominican Republic, Eswatini, Hungary, Saudi Arabia and Ukraine.

In “normal times”, public expenditure reviews, social budgeting and other types of budget analysis can be used to assess the current spending structure and, when politically feasible, provide advice to replace high-cost, low-impact investments with investments that result in more substantial socio-economic impacts and redistribution. Egypt, for instance, removed its energy subsidies and planned to reallocate 1 per cent of GDP to social protection expenditure (even though this target was not achieved by 2019) in the form of additional food subsidies, cash transfers to older persons and low-income families and other targeted social programmes, including more free school meals

Significantly, social protection spending should not be seen as competing with other important social and structural spending, such as spending on health, education and basic infrastructures. Through synergies between social protection and other sectors such as health and education, parts of the fiscal space created for social protection can also benefit those other sectors, thereby enhancing spending effectiveness (for example higher enrolments in schools thanks to family allowances or school feeding programmes). Social health insurance contributes to the sustainable financing of the health sector by creating a solvent demand for quality health care services. These synergies need to be reflected in countries’ national development plans, integrated national financing frameworks and medium-term fiscal frameworks, as outlined in section

Enhancing spending effectiveness also refers to making improvements in the design and performance of social protection schemes and programmes to achieve intended development outcomes, such as poverty reduction, redistribution or lower maternal and child mortality rates. For example, Costa Rica introduced a new health care model that strengthened prevention and health promotion, leading to substantial improvements in spending effectiveness in terms of health outcomes. The introduction of categorical social protection schemes (that is, identifying beneficiaries based on simple criteria such as age) instead of (proxy-)means-tested programmes increases efficiency since such schemes typically have lower administration costs and can be implemented more rapidly. They also entail fewer of the targeting errors that can be detrimental to creating trust in the system.

3.3 Managing debt through borrowing or restructuring debt

Managing sovereign debt through borrowing and debt restructuring involves actively exploring domestic and foreign borrowing options at low cost, including concessional loans, following careful assessment of debt sustainability and in line with the national circumstances. For example, South Africa issued municipal bonds to finance basic services and urban infrastructure

Adopting a more accommodating macroeconomic framework creates an enabling macroeconomic condition for exploring domestic and foreign borrowing options. It may also entail allowing for higher budget deficit paths and higher levels of inflation without jeopardizing macroeconomic stability. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, regional unions, such as the European Union and the Africa Economic and Monetary Union, have relaxed their fiscal deficit rules to allow countries in their respective regions more flexibility to respond to the urgent needs arising from the pandemic. Finally, the argument in favour of a debt moratorium – delaying the payment of debts or obligations – and debt cancellation has gained strength during the COVID-19 pandemic. International coordination on debt, for instance in the form of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, will be critical.

The role of international technical and financial support and coordination

Nonetheless, given the significant gaps in social protection coverage and unmet financing needs, in particular in low-income countries, and also given that increasing domestic resource mobilization might take some time, national resources are not sufficient to achieve SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 by 2030 in particular and the SDGs in general

Box

Recommendation No. 202 states that countries whose economic and fiscal capacities are insufficient may need to seek international support, at least in the short-to-medium term. This is also called for by SDG target 1.a, which urges countries to “ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions”.

The importance of development cooperation was further highlighted in the Conclusions concerning the second recurrent discussion on social protection (social security) adopted by the International Labour Conference at its 109th Session in 2021 (ILO 2021f). In line with its constitutional mandate to set international social security standards, its tripartite structure and its technical expertise, para. 21 (c) states that the ILO should:

“explore options for mobilizing international financing for social protection, including increased official development assistance, to complement the individual efforts of countries with limited domestic fiscal capacities to invest in social protection or facing increased needs due to crises, natural disasters or climate change, based on international solidarity, and initiate and engage in discussions on concrete proposals for a new international financing mechanism, such as a Global Social Protection Fund, which could complement and support domestic resource mobilization efforts in order to achieve universal social protection

International support is not only a matter of global solidarity but also an issue of political and legal responsibility. In its general comment No. 19: The right to social security (art.9), adopted in 2008, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights emphasized that the right to social security also includes extraterritorial obligations and that:

“(d)epending on the availability of resources, States parties should facilitate the realization of the right to social security in other countries, for example through provision of economic and technical assistance. … Economically developed States parties have a special responsibility for … assisting the developing countries in this regard”.7

4.1 Technical support

The need to assist domestic resource mobilization for social protection through technical support has been recognized before and was most recently confirmed at the 109th Session of the International Labour Conference in 2021. Since 2009, UN agencies have joined efforts to support the development of national social protection strategies and systems, including a solid national social protection floor that leaves no one behind. This was reflected in UN development assistance frameworks in many countries and led in 2019 to the development of 35 joint Sustainable Development Goals Fund programmes on integrated policy solutions for social protection to Leave No One Behind

In a similar vein and in line with ILO’s constitutional mandate to support Member States’ development of their social security systems, notably through the Global Flagship Programme on Building Social Protection Floors for All (2016–2030) (ILO 2021k; 2021l), the ILO supports the design and implementation of national social protection systems including floors through in-country support; cross-country technical advice; the development of practical tools and knowledge exchanges; and forging strategic partnerships, including with UN agencies

While these initiatives have contributed to increasing coordinated support for countries in building national social protection systems, the need to link policy advice to feasible financing options has become more prominent. An ongoing European Union (EU) action implemented jointly by the ILO, UNICEF and the Global Coalition for Social Protection Floors

4.2 Financial support

Considering their significant unmet social protection financing needs, the individual efforts of countries could be complemented and supported by international financing for social protection, based on international solidarity. This might apply to countries with limited domestic fiscal capacities to invest in social protection or countries that face increased needs because of a crisis, a natural disaster or climate change. Such financial support could, for example, complement national budgets to finance non-contributory social protection or support the development of adapted (for example temporarily subsidized) social insurance for workers and enterprises in the informal economy.

To some extent, this has already been done in the context of socio-economic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Bangladesh received a grant of €113 million from the EU and Germany’s Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau to co-finance a large emergency package, including a cash transfer programme for unemployed and distressed workers in the ready-made garment, leather goods and footwear industries. Bangladesh also received a concessional loan of €150 million from the French Development Agency for a contingency emergency response for poor and vulnerable populations.

In general, there are several ways to channel international financial support, including ODA, such as through project-, results- or policy-based financing; direct budget support, with a specific focus on improving public finance management and social protection systems performance; dedicated “basket” funds at the national level that pool resources from national and international actors; or a global fund for social protection

Joint financing arrangements at the national level

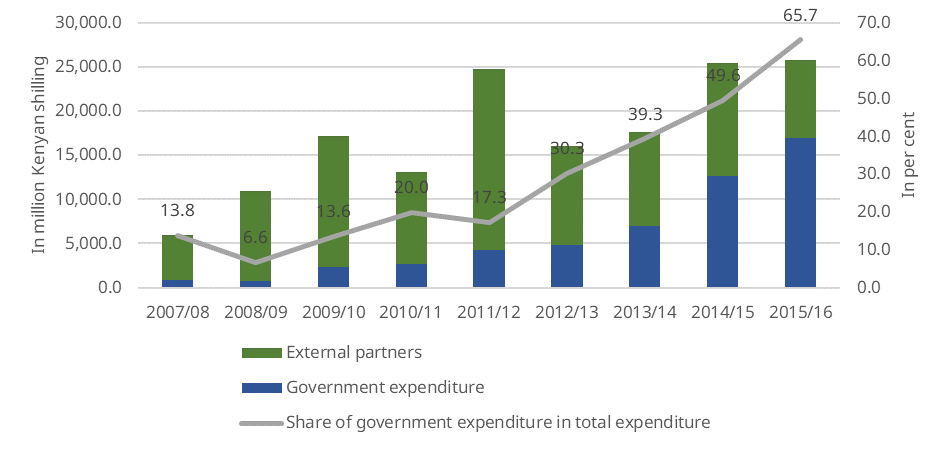

Most low- and lower-middle-income countries are in the process of building national social protection systems. Universal social protection cannot be achieved immediately but only in a progressive manner, as institutional capacities are developed. As a result, financing needs will increase each year as social protection systems mature and cover more people and more risks with higher levels of benefits. At the same time, in line with international social security standards that stress the overall and primary responsibility of the State and the principle of financial, fiscal and economic sustainability of social protection systems

Both factors need to be considered when discussing joint financing arrangements. In the context of an emergency response such as in the case of the COVID-19 crisis, natural disasters or other shocks, temporary support could be extended to assist countries during the months or years needed to cushion immediate shocks or to adopt and implement their domestic resource mobilization strategies.8 In the longer run, countries that progressively build national social protection systems will also be in a better position to respond quickly to future shocks and to use additional financial support to scale up and extend existing schemes and programmes

Moreover, financial support needs to be offered along with technical support – as requested and required – to assist countries in efforts to increase domestic resource mobilization and create a social protection system that is universal, comprehensive, adequate and sustainable

Box

During the COVID-19 crisis, workers in the garment sector have been affected by factory closure and the reduction of working time. The objective of an ILO–Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany (BMZ) project (2020–2022) was to support them during this difficult period.

In the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, which already had a functional unemployment insurance system, the project provided additional unemployment benefits to affected workers. The project could make use of the existing social security infrastructure and the disbursement of the emergency support was very smooth.

In countries without any functional unemployment insurance (Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ethiopia, and Indonesia), the project had only a few months to implement a completely new solution to distribute cash. These solutions had to comply with ILO social security standards, notably the principles of social dialogue and tripartite representation, adequacy of benefits, transparency, and non-discrimination.

The mid-term evaluation of the project, which was conducted in 2021, highlighted that financial assistance to countries (such as the assistance provided by BMZ) can complement and support national efforts to build social protection systems but cannot replace them. Through this project, national constituents with ILO support used the guidance provided by international social security standards to build emergency solutions and achieved institutional changes and advances in the social security system that can today support a more inclusive recovery.

Subsidizing social security contributions through a basket fund to facilitate the extension of coverage to currently unprotected workers in the informal economy is currently being discussed in Jordan in the context of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see

Box

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Jordanian Social Security Corporation, with the technical support of the ILO and other partners, has decided to set up a special fund for employment support and formalization of vulnerable workers, known as the Estidama++ Fund – Extension of Coverage and Formalization.

A first contribution to the fund has been agreed by the Governments of Norway and the Netherlands and it is expected to start operations in the 1st quarter of 2022. Additional donors are expected to join the pooled fund in an anticipated second phase and matching funds from the Government are also under discussion. The fund will therefore allow Jordan to advance its agenda of extension of coverage of the social insurance system to the “missing middle”, while preserving the long-term financial sustainability of the Social Security Corporation for currently insured members. This approach is framed within the Jordanian national social protection strategy (2019–2025) and in line with ILO social security standards, including the principles of financial sustainability; solidarity in financing; sound governance; and coherence with social, economic and employment policies. Lessons from the first phase of the implementation will inform further expansion and consolidation of the fund.

Similarly, Togo has established the Novissi income support programme for workers in the informal economy affected by the socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The confidence generated by the Novissi’s timely provision and the digital enrolment and payment system built in the context of the programme could be used to encourage workers in the informal economy to register under an adapted contributory scheme that is currently being developed by the National Social Security Fund. The lessons learned in the use of digital technology could also inform the rapid enrolment of the categories of people targeted by the medical assistance scheme within the implementation of the universal health insurance law adopted on 9 September 2021.

The duration of the joint financing arrangements would need to match the time needed to undertake the necessary policy and fiscal reforms and to build national institutions and capacities. The annual levels of complementary financing also need to be predictable so that countries have sufficient time to mobilize resources domestically and can ensure that benefits can be paid, in line with the principle that entitlements to benefits should be adequate, predictable and prescribed by national law, establishing rights for beneficiaries

The schedule should also allow for some flexibility should circumstances change unexpectedly, a fact demonstrated dramatically by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, this has also been experienced before, taking the instructive example of cyclone Idai and its devastating impacts in Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe in 2019, as well as many other potential events (for example a global economic recession, a food crisis and so on). These financing arrangements will need to be further elaborated, also taking into account the experience of existing global funds and the solidarity or basket funds established at the national level as in the case of Jordan (see

Figure 4: Share of external and domestic financing for non-contributory social protection schemes, Kenya, 2007–2018

Prerequisites for international financial support and prioritization

International complementary financing arrangements need to be agreed upon in the context of partnership frameworks that foster mutual accountability in achieving shared outcomes

These standards not only define a tangible goal – setting up national social protection floors – but also define principles for guiding countries towards achieving these objectives

Additional prerequisites for financial support may include having at least one national social protection programme or scheme in place that would be available to absorb additional resources and distribute the benefits and could be scaled up, or the political will to establish a new national social protection scheme and progressively increase domestic resources for social protection. For all countries requesting financial support, it would also be necessary to have adopted and costed a strategy for the development of a national social protection floor and conducted a fiscal space analysis that establishes that the economic and fiscal capacities to guarantee the national social protection floor are insufficient and that national efforts need to be complemented with international resources, at least temporarily. Moreover, countries and financial and technical support institutions should agree on a credible, feasible and sustainable medium-term exit strategy from such financial support that is in line with medium-term revenue and expenditure frameworks and/or embedded in integrated national financing frameworks.

The prioritization of countries for financial support (and technical assistance) could take into account existing coverage gaps and financing needs as well as the current income classification, with a focus on low-income or lower-middle-income countries for the financial support component.

International resources to meet countries’ financing needs

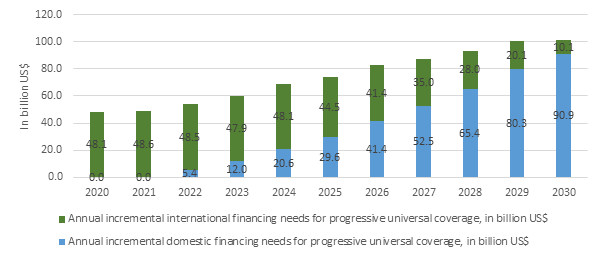

These considerations at the country level – combining progressively increasing total resource needs as social protection systems are established and decreasing international resource needs as domestic resource mobilization is strengthened simultaneously – are the basis for providing the estimate of resource needs from international sources between 2020 and 2030 based on the estimated financing needs presented in

The blue bars indicate the annual incremental domestic financing needs for building social protection floors in low-income countries. The green bars show the corresponding amounts that would need to be financed from international resources, such as Special Drawing Rights or ODA. This assumes that given the strain of the current COVID-19 pandemic, financing needs would need to be covered fully from international resources in 2020 and 2021. From 2022 onwards, it is assumed that the share financed from domestic resources progressively increases by 10 percentage points each year and international partners’ co-financing is continuously phased out accordingly. This means that in 2026 only half of low-income countries’ financing needs would need to be financed from international sources and in 2030 only 10 per cent would need to be financed. Subsequently, international financial support would aim merely at safeguarding investments in the case of covariate shocks.

Figure

To ensure progressive implementation, avoid retrogression and increase credibility and trust in the social protection system, it is crucial that recipient countries can rely on international financial support over a clearly defined and sufficiently long time period that allows for strategic planning and undisrupted support. This follows from the principles that social protection schemes and programmes should be anchored in national legal frameworks and benefits should be predictable. The inability to fulfil legal commitments could lead to legal claims from beneficiaries, lack of trust in the system and social unrest.

While international resource mobilization and debt relief have provided important short-term financial assistance in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, they represent only a small proportion of what is needed to sustainably close the social protection financing gap in low- and middle-income countries. Previous commitments exist as well, yet despite the Addis Ababa Action Agenda’s call for enhanced ODA to support financing for sustainable development (United Nations 2015), many countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)/Development Assistance Committee (DAC) fall woefully short of meeting the agreed target of 0.7 per cent of gross national income (GNI); preliminary figures for 2019 show an average value of 0.3 per cent of the combined GNI of all OECD/DAC countries

Encouraging and supporting the mobilization of international resources for social protection, including through increased ODA, is therefore needed. In reality, the share of disbursed ODA allocated to social protection represented a mere 1 per cent of total bilateral ODA in 2018

To complement regular sources of financing and fill remaining gaps, donor (but also recipient) countries could consider a range of innovative sources of financing, some of which have already been implemented. These include earmarked taxes (financial transaction taxes, taxes on airline tickets, dedicated funds from extractive industries, sin tax on tobacco, alcohol and fast food, billionaires’ tax, inheritance tax, arm trade taxes, levies on mobile phone calls and so on); debt-based borrowing mechanisms (debt conversion linked to social protection, diaspora bonds and so on). Overall, these sources of financing vary in terms of several criteria that should be taken into account for policy considerations, including the objectives of the financing sources, their time frame, whether they are earmarked, the level at which they would be raised, their overall sustainability and the political will to implement them (Durán Valverde et al. 2020, table 9).

4.3 International coordination to increase domestic resources for social protection

Finally, it will be essential that the strategic objective of establishing basic social security guarantees to all and building universal social protection systems is supported by the multilateral system through enhancing the coherence of national and international policies and creating an environment that is conducive to increasing fiscal space at the domestic level. This will require strong political will and the active mobilization of IFIs and development partners. This is also in line with the proposed pillars of the Global Accelerator for Jobs and Social Protection (see

Furthermore, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the argument in favour of a debt moratorium (delaying the payment of debts or obligations) and debt cancellation is gaining strength. In this regard, G20 finance ministers agreed on a debt “standstill” in 2020, which allowed for the postponement of debt repayments from 73 eligible low-income countries. The debt standstill was extended until end-2021 to reduce strain and provide some support to the poorest countries. This measure corresponds to the first phase of a three-pronged approach to debt, as outlined in a report of the UN Secretary-General issued in May 2020

Conclusion

In 2008, a financial and economic crisis hit every region and country in the world. Countries that already had social protection systems in place, covering all or a large part of their populations, were the first to offer an adapted response to individuals and companies affected by the crisis. They were also the first to bounce back and find the path to economic growth. Social protection was rightly seen as an automatic stabilizer in times of crisis. On this promising basis, the UN launched the Social Protection Floor Initiative as one of nine initiatives to address the crisis and accelerate economic recovery. Since then, many countries, convinced of the role that social protection plays in economic and social development, have significantly extended coverage to their populations, whether for health care, children, persons with disabilities, older persons or persons of working age. UN agencies, joined by many development partners, also increased their support for the development of national social protection systems in order to make the right to social security a reality for all. Despite this enthusiasm and these developments, investment in social protection systems, whether through contributory or tax-financed schemes, has remained largely insufficient and partly explains why today one person in two lives without any social protection.

Achieving SDG targets 1.3 and 3.8 by 2030 would require developing countries to invest between 1.9 and 2.4 per cent of GDP per year over and above what they already invest

For low-income countries, the situation is quite different. Closing financing gaps would require a much larger effort, in the range of 9.8 to 12.1 per cent of GDP. This does not seem feasible by 2030 without significant support from the international community. Such support would be financial as well as technical to enable countries not just to distribute aid but also to build robust systems with legal entitlements and strengthen the national capacity to collect more taxes and contributions in order to provide a social protection floor for all. This is where technical and financial support must be sufficiently coordinated to promote a shared, national vision of social protection development. This coordinated approach can only work if all actors, national and international, systematically apply international social security standards and demonstrate a strong commitment to building universal, comprehensive, adequate and sustainable social protection systems.

Investing more in social protection would build a more stable, just and sustainable world, in which everyone has access to health care and protection of their livelihoods in the event of job loss, illness, maternity or disability and during childhood and old age. Social protection systems, including social protection floors, prevent and reduce poverty, inequalities and insecurity. Building social protection systems, including strong floors, not only changes people's lives and gives them peace of mind but also increases domestic demand for goods and services and creates an investment in worker productivity. It contributes to inclusive economic recovery and further economic development. By putting solidarity into practice, social protection recreates the social fabric that has been strained by large-scale global transformations and also recently by COVID-19 lockdown measures.

Annex

Table A.1: Incremental financing needs for progressively closing the social protection floor coverage gap in low-income countries, 2020–2030 (billions of US$ and percentage of GDP)

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

2030 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Low-income countries |

In billion US$ |

48.1 |

48.6 |

53.9 |

59.9 |

68.7 |

74.1 |

82.8 |

87.4 |

93.4 |

100.3 |

100.9 |

|

In per cent of GDP |

9.80 |

9.45 |

9.90 |

10.38 |

11.23 |

11.41 |

12.02 |

11.95 |

12.01 |

12.14 |

11.49 |

|

|

Lower-middle-income countries |

In billion US$ |

203.2 |

209.3 |

219.7 |

240.0 |

268.4 |

296.1 |

326.3 |

351.7 |

379.4 |

406.7 |

413.4 |

|

In per cent of GDP |

2.83 |

2.74 |

2.72 |

2.80 |

2.96 |

3.08 |

3.20 |

3.25 |

3.31 |

3.35 |

3.21 |

|

|

Upper-middle-income countries |

In billion US$ |

517.6 |

523.2 |

409.4 |

443.3 |

479.1 |

518.0 |

551.1 |

586.2 |

620.9 |

657.9 |

686.3 |

|

In per cent of GDP |

2.17 |

2.04 |

1.52 |

1.56 |

1.61 |

1.65 |

1.66 |

1.68 |

.1.69 |

1.69 |

1.68 |

|

|

Low- and middle-income countries |

In billion US$ |

769.0 |

781.0 |

683.0 |

743.2 |

816.2 |

888.3 |

960.2 |

1025.3 |

1093.7 |

1164.9 |

1200.7 |

|

In per cent of GDP |

2.44 |

2.31 |

1.92 |

1.98 |

2.07 |

2.13 |

2.18 |

2.21 |

2.23 |

2.25 |

2.19 |

References

———. 2021k. “ILO Global Flagship Programme on Building Social Protection Floors for All: Report of the First Phase 2016-2020.” Geneva: International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/secsoc/information-resources/publications-and-tools/TCreports/WCMS_822164/lang--en/index.htm.

———. 2021l. “ILO Global Flagship Programme on Building Social Protection Floors for All: Strategy for the Second Phase 2021–2025.” Geneva: International Labour Office. https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/RessourcePDF.action?id=57506.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws heavily from a study on financings gaps for targets 1.3 and 3.8 of the Sustainable Development Goals by Durán Valverde et al. (2020) and a summary of it in the form of a policy brief (ILO 2020a), as well as the Resolution and conclusions concerning the second recurrent discussion on social protection (social security) adopted at the 109th Session of the International Labour Conference (ILO 2021g).

The authors are grateful for the inputs and comments received by their colleagues in the ILO (in alphabetical order): Sandra Patricia Alves Lopes Silva (Social Protection Coordinator and EUESF Manager), Christina Behrendt (Head, Social Policy Unit), Andre Felipe Bongestabs (Project Officer), Fabio Durán-Valverde (Specialist, Social Protection and Economic Development, former Head, Public Finance, Actuarial and Statistic Unit), Abalo Essodina (National Project Coordinator), Claire Harasty (Special Advisor to the DDG/P on Economic and Social Issues), Aurelie Klein (Social Protection Officer), Ursula Kulke (Specialist in Workers’ Activities, ACTRAV), Kroum Markov (Social Protection Policy Specialist), Karuna Pal (Head, Programming, Partnership and Knowledge-Sharing Unit), Luca Pellerano (Senior Specialist, Social Security), Celine Peyron Bista (Chief Technical Adviser on Social Protection), André Picard (Head, Actuarial Services Unit), Alvaro Roberto Ramos Chaves (Technical Expert, Social Protection Financing), Shahra Razavi (Director, SOCPRO), Helmut Schwarzer (Head, Public Finance, Actuarial and Statistic Unit), Carlos André da Silva Gama Nogueira (Social Protection Programme Manager), Maya Stern-Plaza (Social Protection Legal and Standards Officer), Lou Tessier (Health Protection Specialist), Stefan Urban (Social Protection Officer), Ruben Vicente Andrés (Social Protection Programme Manager).

Special thanks are due to numerous colleagues from other organizations (in alphabetical order): Doerte Bosse (EC), David Bradbury (OECD), David Coady (IMF), Michael Cichon (Actuarial economist, former advisor of the GCSPF, former Director of ILO Social Protection Department), Quentin Comet (Global Sovereign Advisory), Jürgen Hohmann (former EC), Markus Kaltenborn (GCSPF), Anne-Laure Kiechel (Global Sovereign Advisory), Thibault van Langenhove (formerly AFD, Expertise France), Benedikt Madl (EC), Marcus Manuel (ODI), Dennis Pfutterer (KfW), Ana Rachael Powell (Executive Office of the UN Secretary-General), Delphine Juliette Prady (IMF), Oliver de Schutter (Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights), Alison Tate (ITUC), Nicola Wiebe (Brot für die Welt/GCSPF), Bettina Zoch-Oezel (KfW).

The paper also benefited greatly from exchanges with Anousheh Karvar (Delegate of the French Government to the ILO’s Governing Body, as well as the Labour & Employment Task Officer to the G7 and G20) and Martin Denis (French Ministry of Labour) and many other policymakers and technical experts.