(Un)Employment and skills formation in Chile: An exploration of the effects of training in labour market transitions

Abstract

Labour markets are currently undergoing tremendous challenges. Automation, skilled-biased technological change, or offshoring are transforming challenges and opportunities for workers. In this context, international organizations have highlighted the crucial role of labour market policies and institutions, particularly but not exclusively re-training and skills formation policies, to cope with the said transformations and allow individuals to better adapt and benefit from them (for example

Introduction

Labour markets are currently undergoing tremendous challenges due to the combined effects of the knowledge economy and associated technical change. Processes like automation, skilled-biased technological change and offshoring are expected to have dramatic social, economic and political consequen

Existing research on the effects of these transformations, including on skills formation, has concentrated on advanced economies; there is still a large gap in understanding what happens in less advanced economies, where there is a higher prevalence of underemployment, informality and routine jobs

In this paper, we analyse the effects of training on labour market transitions in Chile, using available longitudinal data. We focus on the transitions from unemployment to employment and between different types of employment. The case of Chile is particularly interesting owing to the constant portrayal of this country as a successful case in terms of educational achievement and employment in the Latin American context, as well as its characteristic pro-market labour training system, which has come under increasing criticism (see Bogliaccini and Madariaga 2021; Sehnbruch 2006). Using individual-level panel data spanning seven years of individuals’ work trajectories and training instances, we estimate the average effect of attending training courses while unemployed on individuals' yearly ratio of unemployment. In addition to this, we explore whether training improves the probability of workers changing occupational categories. Our results suggest that there is a small but still significantly positive effect of training, of about 4.3 to 4.5 percentage points, in reducing post-training unemployment events. The baseline – pre-treatment – yearly average unemployment for individuals with at least one month of unemployment during the period between 2009 and 2015 is 3.3 months. Post-training yearly unemployment among individuals attending training while unemployed is, on average, reduced by half a month. For employed workers, results show how training occurs mostly between highly educated workers or workers in very specific occupations.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we review the literature on the relationship between skills formation/training and labour market outcomes, focusing on the effect of training on employment transitions. Second, we describe our case, data and model specifications. Third, we present and discuss the results of the model estimations. Finally, we provide an assessment of the results of this study considering contemporary labour market challenges.

Skills and labour markets

Since the seminal contributions of Jacob Mincer, Thomas Schultz and Gary Becker in the 1960s, the study of the relationship between human capital and labour markets has gained wide notoriety. Studies have evolved from general assessments of the labour market outcomes of huma

There is a widespread idea that more years of schooling are related to better labour market outcomes, including employment and earnings. The literature considers education and the skills acquired in educational environments to be the key to understanding differentiated labour market performance, higher overall productivity an

There are many definitions of training in the literature because concrete training experiences and modalities vary widely (Wilson 2013; Fitzenberger

Although training is closely related to the adaptation to highly demanding international markets and new technologies, training is also commonly used to improve the labour market chances (employment, formality, earnings) of populations that are affected by different kinds of vulnerabilities. These include people with low formal education, those too young or too old, minorities facing discrimination in the labour market, or those with high family and care responsibilities (Wilson 2013, 10; Kallberg 2009, 10; Crépon et al. 2007, 2; Kallberg 2009, 10). Importantly, labour market vulnerabilities often intersect, that is, those with lower or no qualifications tend to accumulate other barriers to work such as disability, caring responsibilities, or belonging to ethnic minorities (Wilson 2013, 17). What is more, labour market vulnerabilities may not only affect people who directly suffer from them but can also be passed on to their offspring, producing cumulative disadvantages across generations (Lindemann and Gangl 2019). Research suggests that training probabilities are strongly related to these vulnerabilities. In fact, having experienced longer unemployment spells decreases the probability of entering training (Crépon

In sum, due to existing labour market vulnerabilities, cumulative disadvantage and widespread labour disparities, several authors highlight the key role of training to improve labour market chances and outcomes (Wilson 2013, 17; Dixon and Crichton 2006, 1; Acemoglu and Pischke 1999, 112–113). In fact, active labour market policies, where training is a key component, are increasingly designed to help these more disadvantaged workers (Wilson 2013, 5).

Existing evaluations of training policies have found mixed results at best, or no results at worst, in relation to their effect on employment outcomes (Wilson 2013, 5). As we will see, the range of possible design features of training programmes affecting different outcomes is a crucial source for this. Regarding the outcome of interest, most evaluations concentrate on unemployment-to-employment transitions, distinguishing between how rapid the re-entry into the labour market is. However, other possible dependent variables include the duration of future employment, the quality of future employment and the duration of current and future unemployment spells. Some studies even concentrate on the probability of entering employment programmes. The least covered, albeit no less important, is the cost-effectiveness of programmes (Wilson 2013, 24). The latter is even more important if we consider what authors call deadweight effects, that is, that often results may have happened even in the absence of an intervention (ILO 2016, 103).

Reported results tend to vary by programme characteristics, participant characteristics, or by the institutional characteristics of the countries where these programmes take place (see Comyn and Brewer 2018, 25). Regarding the first, Wilson (2013, 7) highlights that “it is program design that matters most” for results, and particularly, the size and duration of programmes (Wilson 2013, 22). Authors underscore that, in general, smaller programmes that can be tailored to local labour markets are more effective than larger-scale ones. On the other hand, they point to a trade-off between short-term and longer-term employment gains: while longer programmes reduce short-term employment gains, what the literature calls the “lock-in” effect or the decrease in job search for the duration of the training programme, they increase employment chances and duration in the longer run (Fitzenberger

Conversely, effects can also vary by quality of employment, that is, effects can change if we consider finding a “sustained” job—as opposed to “any job” (Calderón-Madrid 2006, 4; Crépon

Another design feature that affects results is the orientation to labour market demands and the employer's input. The more programmes are oriented to labour market demands as opposed to their supply, the better they integrate the concerns of local employers and the better the results they achieve (Wilson 2013, 20; Comyn and Brewer 2018, 1; Crépon

The second source of consideration for the outcomes of training programmes is the institutional characteristics of the countries in which they take place, such as how regulated labour markets are, the type of welfare/family policy benefits, employment protection and the presence of trade unions. Likewise, the literature has no clear answers to these: while some point to more flexible labour markets and institutional conditions as more conducive to effective training (Wilson 2013), others point to more protective labour markets to increase the probability of training (Arulampalam and Booth 1998, 3–4; Smyth 2018, 8–9; see Acemoglu and Pischke 1999).

Finally, the third type of study concentrates on how the personal characteristics of trainees affect the results of training, including: prior employment experience; education levels, and age (Dixon and Crichton 2006; Veinstein and Sirdey 2016, 8; Crépon

With respect to education and socio-economic status, Veinstein and Sirdey (2016, 8) report that undereducated young people find it harder to obtain stability in their newly acquired jobs after being trained, as opposed to those with better qualifications, but as Arulampalam and Booth (1998, 8–9) find, more precarious workers receive more training than workers in more stable employment. Conversely, Wilson (2013, 17) cites studies that find positive effects on outcomes for young men without qualifications but little effects for those with higher qualifications.

With respect to the probability of being trained, younger individuals have a higher probability of receiving training, but this depends on the flexibility of early retirement arrangements: when more flexible, older workers make higher use of training than in more rigid contexts (Fouarge and Schils 2009, 91). Moreover, having experienced recurrent unemployment spells in the past decreases the probability of participating in training (Crépon

To complicate matters even further, there is no clear evidence that when effects are present, these are attributable to the skills acquired. It may be, for example, that they result from an increase in “self-confidence”, implying that training raises the unemployed person’s perception of his/her own employability (Crépon

Most studies hitherto reviewed concentrate on advanced countries. However, Latin American countries like Chile have a number of differences in terms of institutional characteristics of the labour market and educational/training systems, as well as diverse social structures. These make the functioning of training systems vary. Overall, Latin American labour markets show higher informality, higher labour turnover, higher wage inequality and a lower overall skills level than other regions, including other developing regions (see more on this below). This implies that training in general, and active labour market policies (ALMP) in particular, usually need to aim for a diversity of labour market and social inclusion objectives and comprise multiple interventions and measures (see ILO 2016). In fact, since the 1990s training and ALMP have been increasingly directed to those in chronic unemployment and precarious work.

Two recent works (ILO 2016; Escudero

All in all, these evaluations suggest that training programmes, particularly those that are part of ALMP interventions, have a larger impact in Latin America than they do in OECD countries, and that this may be partly explained by their characteristic multiplicity of objectives and interventions (Escudero

In the case of Chile, against initial evaluations that found positive effects, more recent ones found inconclusive results on employment and small effects on salaries dependent on the characteristics of the programmes such as duration (longer programmes have stronger effects) and the inclusion of some type of apprenticeship or internship (Comisión Nacional de Productividad (CNP), 135–136; 139; Comisión Revisora 2011, 23; 26–9; 43–44). Sehnbruch (2006, 197), however, reports that some of the positive results – for example in the case of the

Case study, data and model specifications

2.1 Case study

Chile is a paradigmatic case of what Schneider and colleagues (Schneider 2013; Schneider and Karcher 2009) have called “hierarchical market economies”. In hierarchical market economies, the most dynamic enterprises form part of a small segment of large, international business groups, which have diversified their activities between retail, protected public service sectors and extractive industries. These sectors demand little product innovation processes and workforce skills. This is reinforced by a strong segmentation between an elite of protected workers and a mass of mostly informal, unprotected and highly rotating labourers. In this context, training is overall scarce and/or is internalized by large, international enterprises.

Although Chile is among the countries with the lo

In terms of education, the focus is on academic programmes leading to high school diplomas and tertiary education directed towards academic tracks. The vocational education track (both at secondary and tertiary levels) has grown in importance over time, although it is directed mostly towards the least advantaged pupils and has been highlighted for its detachment from actual skill demands (Bogliaccini and Madariaga 2021; CNP 2018). This educational system is highly segmented and results from standardized tests showing very poor outcomes in terms of educational quality and the skills acquired through formal educational processes, both when measured at the student level (Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)) and at the worker level (Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)) (CNP 2018). Thus, while showing higher attainment rates than the rest of Latin America, and closer to OECD countries, in Chile education quality and inequality issues are more reminiscent of Latin America’s problems (see Bogiaccini and Madariaga 2021).

Chile’s vocational training system was founded in the 1950s to aid the process of import-substituting industrialization but was significantly overhauled during the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1970s when it was privatized and reorganized around free market orientations (see Sehnbruch 2006). Its importance has grown over time, from around 2.6 per cent of the workforce receiving training in the mid-1960s (Sehnbruch 2006, 176) to about 13 per cent in 2016.3 This system is composed of mostly two modalities provided through the

The second modality consists of publicly funded programmes for retraining the population with low education and employability, including active labour market programmes for the unemployed. They tend to provide longer hours of training and higher expenditure per capita (despite lower per hour expenditure) (CNP 2018, 124–5). In this modality, there is a great diversity of programmes that target the same population and have little connection between them and to labour demand (CNP 2018, 123). As of 2016, 15 per cent of those trained participated in this modality.

The SENCE is a public institution in charge of coordinating courses through private or public organizations. Programme provision is made mostly by private institutions or

Several reforms have attempted to strengthen the targeting of both training modalities for lower-earning workers and smaller firms, as well as to improve coordination between employer demands and the supply of training courses, to avoid creaming and deadweight costs. The latest reforms included the implementation of a framework for skills certification (

2.2 Data

The

The EPS is organized into several issue-related modules. The module on employment histories (module B) incorporates all labour histories in the survey period (2009–2016) for each person (folio). It provides information on the occupation, occupational sector and contractual status of the workers, as well as questions about the reasons for inactivity (for example, maternity, studies and illness) and the period of unemployment. The module on training (module G) contains information on the number and other characteristics of training courses in every survey round.

In working with the EPS data we made the following decisions: (i) we excluded from the analysis the labour histories (before 2009) of newly incorporated replacements into the 2015 round; (ii) in the case of people with a labour history that spanned more than one year, we coded the information in that labour history for all the corresponding years; (iii) we excluded the information for 2016 because the data were incomplete (available only until April 2016).4

2.3 A descriptive initial picture

Chile has a low incidence of training in the labour force. This is like other Latin American countries but below OECD levels. According to our data, close to 13 per cent of respondents received some type of training between 2009 and 2015 (1,516 people out of a total of 16,906 respondents). Among the economically active population, 90.5 per cent of training occurs among employed individuals, while 9.5 per cent among the unemployed (table 1). The two groups show several differences in terms of their training patterns. In terms of gender balance regarding those trained by labour force status, those who train while employed are mostly men (53.4 per cent), while those who train while unemployed are mostly women (60.4 per cent). In terms of age, those who train while employed are mainly in their mid-career, that is, between the ages of 31 to 45 with close to 39.5 per cent, followed by late-career (46 to 65), with 32 per cent and finally those in their early career (18-30) with less than 30 per cent. Conversely, training while unemployed is concentrated among those in their early career. In fact, these represent almost three quarters of all trainees in this labour force status, followed by late-career (close to 20 per cent). Only 5.4 per cent of those in their mid-career train while unemployed/inactive. These differences coincide with the profile of training programmes for the employed (

Table 1: Labour force status of participants in training programmes

|

% |

|

|

Employed |

90.5 |

|

Unemployed |

9.5 |

|

|

|

Source: Author's calculations based on the Social Protection Survey 2015.

Note: Employed individuals refer to those not having episodes of unemployment between 2009 and 2015 and who participated in a training instance. The unemployed category is populated by individuals with at least one month of unemployment during the period who participated in a training instance.

Among those employed and taking training courses, a majority (86.4 per cent) had a written contract while only 13.7 per cent did not. Not having a written contract precludes workers from the benefits associated with the social security system and labour-related protection schemes. Individuals participating in training instances are mostly white-collar workers: scientific and intellectual professionals (22.1 per cent of workers in this category), followed by administrative support staff and technicians and mid-level professionals (table 2).

Table 2: Training by occupational category

|

Training (%) |

||

|

ISCO occupational category |

No training |

Training |

|

1. Directors and managers |

92.0 |

8.0 |

|

2. Scientific and intellectual professionals |

77.9 |

22.1 |

|

3. Technicians and mid-level professionals |

80.3 |

19.7 |

|

4. Administrative support staff |

81.3 |

18.7 |

|

5. Service workers and vendors in shops and markets |

88.8 |

11.2 |

|

6. Farmers and skilled agricultural, forestry and fishing workers |

91.4 |

8.6 |

|

7. Officials, operators and craftsmen of mechanical arts and other trades |

88.6 |

11.4 |

|

8. Plant and machine operators and assemblers |

87.7 |

12.3 |

|

9. Elementary occupations |

92.1 |

7.9 |

|

|

|

|

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Social Protection Survey 2015.

Note: Totals calculated on the total number of workers employed in the survey round, corresponding to 10,764 cases. Omitted cases (8) refer to people who do not have information on the variable of interest.

Most courses were funded by the employer (57 per cent), followed by the Government (22.3 per cent), as shown in table 3. Close to 7.5 per cent of respondents self-financed their training course. This means that the sample contains a comparatively high percentage of people taking government and self-financed courses. As expected, this changes between employed and unemployed, the former taking mostly courses paid by the employer (60.7 per cent), the latter taking mostly government-run programmes (42.5 per cent). As per the institution providing training (table 4), 32 per cent of the courses were taken in specialized OTECs while 26.0 per cent were offered by employers or equipment manufacturers. Another 17 per cent were offered by higher education institutions (universities, professional institutes or tertiary-level technical schools), followed by 7 per cent offered by municipalities and close to 2 per cent by primary or secondary education institutions. For the unemployed, while the OTECs remain the main provider of training (23.6 per cent), the second-most important provider are municipalities (18.1 per cent).

Table 3: Sources of funding for training by labour force status

|

Sources of funding |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Total sample |

|---|---|---|---|

|

% |

% |

% |

|

|

Employer |

60.7 |

19.4 |

56.9 |

|

Government |

22.3 |

42.5 |

24.1 |

|

Person or family |

7.5 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

|

Labour union |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

|

Other |

7.9 |

29.5 |

10.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Social Protection Survey 2015.

Note: The sample size corresponds to the total of those trained in the survey round. Omitted cases refer to people who do not have information on the variable of interest.

Table 4: Institution providing the training, course or workshop, by labour force status.

|

Institution providing the training |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

% |

% |

% |

|

|

Specialized technical training institutions (OTECs) |

32.0 |

23.6 |

31.0 |

|

Employer or manufacturer of equipment |

26.0 |

9.7 |

24.0 |

|

Higher Education Institution |

17.0 |

14.6 |

17.1 |

|

Municipality |

7.0 |

18.1 |

7.6 |

|

Primary/ Secondary education Institution |

2.0 |

11.8 |

2.8 |

|

Other |

17.0 |

22.2 |

17.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Author's calculations based on the Social Protection Survey 2015.

Note: The sample size corresponds to the total of those trained in the survey round. Omitted cases refer to people who do not have information on the variable of interest.

2.4 Empirical strategies

To identify the causal effect of skills formation on unemployment-to-employment transitions, we exploit the panel structure of the EPS data. While some people go through these transitions without investing in skills formation (training), others do invest in skills formation (in other words, receive the treatment). Thus, the identification of the effect of the treatment comes from the comparison of these two groups regarding skills formation.

Our primary estimation strategy is a difference-in-difference design. In our basic estimation, the treatment is binary (0,1) and individuals are assigned to each group depending on their situation regarding skills formation independently of the temporal dimension associated with when the transition occurred. Individuals are assigned to groups only if they have experienced a transition from unemployment to employment.

Our dependent variable is the ratio of unemployed months a year, regardless of the number of individual unemployment spells. For building the variable, we added the total number of unemployed months each year and obtained a proportion by dividing that number by 12. Due to the annual nature of our data, we are unable to correctly measure unemployment or employment spells.

The only sample restriction we imposed is to exclude individuals with more than 11 months of inactivity during the seven-year period (2009–2015). The rationale for this is to analyse individuals who are part of the economically active population and do not become inactive or only do so sporadically. For example, the EPS categorize as inactive a woman during the months after giving birth.5 Other than for substantive reasons, we made this decision to avoid a construct validation issue with our dependent variable, as we are attempting to approximate a ratio of unemployment duration, where lower values in our dependent variable should unequivocally represent more employment. Not excluding inactive individuals would lead to a situation in which lower values in the dependent variable would combine situations of higher levels of employment or higher levels of inactivity. This would highly bias our results.

For the analysis of the transition between unemployment and employment, our control group is composed of individuals, aged 18 to 70 years old, with at least one month of unemployment during the period.

We also model the probability of participating in skills training before and after horizontal mobility between occupational categories. We specifically ask what the probability of participating in skills training is when moving jobs between occupational categories. We run binary logit models to learn such probabilities, interpreting results as discrete changes in the probability of occurrence of a certain outcome.

2.5 Counterfactual assumption for unemployment-to-employment transition: Parallel trends

In the standard difference-in-differences (DiD) model, checking for the absence of pre-trends simply involves comparing trends in the outcome variable in the pre-treatment period across two groups. While the standard DiD model has two periods (pre- and post-treatment) and two groups (treatment and control), we are faced with multiple periods (individuals complete training courses during different years), multiple dosages (since the same subjects can be treated multiple times), and heterogeneous treatment effects (different types of training courses may have different effects).

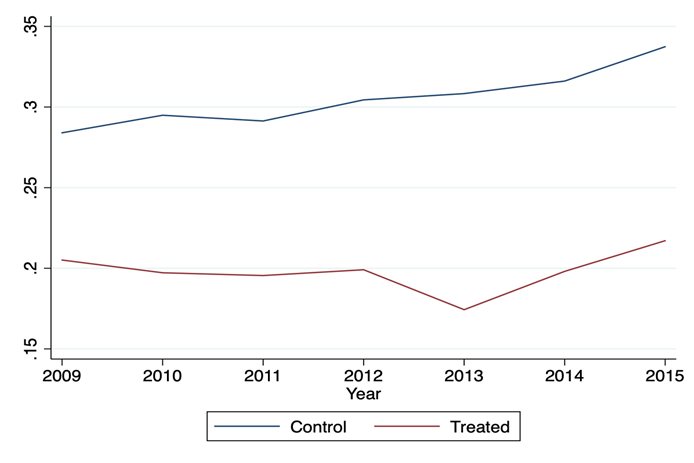

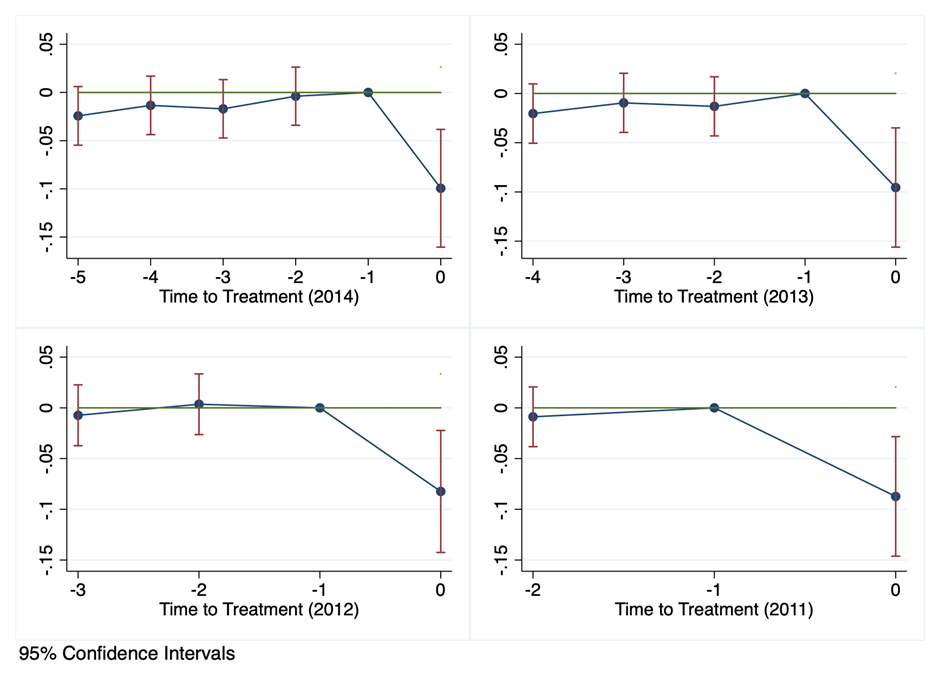

One way to visualize possible pre-trends is to aggregate all training episodes and plot the average months of unemployment per year for the treatment and control groups across windows of before and after training exposure (figure 1). However, a more methodologically appropriate approach, the standard graphical representation in event-study designs, would be to normalize all treatments to a period “0” and compare outcomes before and after that period across groups. We present this in figure 2, which shows the control group having similar average unemployment ratios as the treatment group prior to training exposure in our analyses.

Figure 1: Average proportion of yearly unemployment, treated and control groups

Notes: Average proportion of yearly unemployment is the average of individual records on the ratio of yearly months unemployed for each group.

The graphical analysis suggests that the parallel trend assumption may hold in our unemployment-to-employment transition framework. However, a more nuanced analysis of the parallel trends assumption is in order. Following Roth (2019), we account for the parallel "pre-trend" condition using an event-study methodology. We provide an event-study type of analysis for comparing the two trends. In this analysis, shown in figure 2, we provide evidence of parallel trends for each period of treatment. For each year, the control group is compared only with the group of treated individuals receiving treatment during that period.

In the case of our analysis of skills formation in contexts of unemployment, the event study set up in figure 2 confirms the existence of parallel trends. Unemployed people with and without instances of skills formation are on similar trends during the skills formation period. Given that the parallel trend assumption holds, the DiD identification strategy does not require the groups with and without training instances to be balanced in terms of observable characteristics. However, in our framework, the comparison of the control variables between these groups might help clarify whether the two groups are similar with respect to a set of observable characteristics. Table 8 below compares the average pre-formation values of our control variables for individuals in the two groups.

Figure 2: Parallel trends assumption evaluation

Notes: Each figure shows an event-study analysis comparing the treated and untreated groups for the years 2011 to 2014. Zero represents the year when the treatment occurs. The X-axis represents the time to treatment in each group, measured in years. The estimates (dots) and the confidence intervals (vertical lines) allow us to assess the group's differences with respect to the dependent variable (horizontal line at 0 in the Y-axis). Our database begins in 2009 and we allow for two years as a minimum trend for the analysis in 2011 (lower-right quadrant).

2.6 Estimation for the unemployment-to-employment transition

How does having participated in skills formation affect unemployed individuals? We attempt to measure such an effect using a DiD estimation. Given that we do not have a well-defined level of aggregation in which the treatment occurs because instances of skills formation happen all over the place, we form several treated groups by clustering the treated individuals by year. This design allows treatment in multiple periods. We use two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects, following Chaisemartin and D'Haultfoeuille (2020). The baseline econometric specification is the following:

where

We present two model specifications for dealing with the heteroskedastic distribution of error, after a Breusch-Pagan test (𝝌2=17.03 (0.000)). The widely used robust standard error is calculated as a baseline approach. We also estimate bootstrapped confidence intervals as a robustness check for two reasons: First, the Breusch-Pagan test suggests high levels of heteroskedasticity, under which condition bootstrapped errors might do better. Second, we have a relatively small sample of treated individuals (around 1,500 individuals), for which bootstrapping is a useful robustness check.

2.7. Estimation for training before/after moving jobs between occupational categories

What is the probability of training around the period of moving jobs between occupational categories? We estimate logit models to learn discrete probability choices and for understanding which categories demand more training. We interpret the model results as discrete changes in the probability of occurrence of a certain outcome.

Results and discussion

3.1. The unemployment-to-employment transition

Our results across four main specifications are shown in table 5. We present average results across all periods in the first row. The other rows present fixed effects for each year in the sample. Standard errors are robust in models 1 and 3 and bootstrapped in models 2 and 4.6

Table 5. Average effect of skills formation in transition from unemployment to employment (robust standard errors and bootstrapped confidence intervals)

|

Model (1) Robust Std. Err. |

Model (2) Bootstrapped Conf. Int. |

Model (3) Robust Std. Err. |

Model (4) Bootstrapped Conf. Int. |

|

|

Under Treatment=1 |

-0.0454* |

-0.0454** |

-0.0437* |

-0.0437** |

|

(0.053) |

(0.039) |

(0.060) |

(0.042) |

|

|

Age |

0.00690*** |

0.00690*** |

||

|

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

|||

|

Constant |

0.276*** |

0.276*** |

0.005 |

0.005 |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.954) |

(0.941) |

|

|

Year-fixed effects |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Observations |

11,349 |

11,349 |

11,012 |

11,012 |

*

Our results show that, on average, the treatment effect of participating in a skills formation course while unemployed reduces the ratio of unemployed months by around 4.3 to 4.5 percentage points the following years. This difference is statistically significant and stable across specifications. As a benchmark, the average ratio of yearly unemployment in the sample is 0.3, or 3.5 months.7 Models 3 and 4 include age as a covariate, which is significantly associated with the outcome. At a higher age, there is a higher ratio of yearly unemployment. Our main results are robust to the inclusion of age in the models.

These results speak to works such as Calderón (2006), Crépon, Ferracci and Fougère (2007), or Hirshleifer

Our output measure does not allow us to evaluate the duration of employment or unemployment spells, but provides a year-based estimate of success in being employed. In line with the above-mentioned research pieces, we find a mild but positive effect in the months during a year when trained individuals are employed with respect to their past trends. We also show that these trends are comparable between treated and control groups.

3.2 Training when moving jobs between sectors

The incidence of skills training on job transitioners is almost nil. For the universe of individuals transitioning jobs between occupational categories, we observe which arrival (model 2) or departing (model 1) categories have a significantly different training incidence than the baseline category for arriving at it or departing from it. We defined this baseline category to be “service workers and vendors in shops and markets” (see table 5 for a list of occupational categories) because it is usually a large category demanding general skills, with limited formal training.

The model proposed for this analysis is a binomial logit model. The results are interpreted based on the analysis of the probability of change in the dependent variable (between 0 = non-trained and 1 = trained) given a change of one unit in the independent variable, with all other variables remaining constant at their mean values: Pr (Y = 1|x) (Gelman and Hill, 2007). A first analysis conducted at the centre of the data, the point at which the slope of the logistic curve is most pronounced, reveals the maximum magnitude of the effect of each independent variable on the occurrence of training. At the centre of the data, the probability of occurrence of training when transitioning, in comparison to baseline category, is estimated as the beta coefficient shown in the model divided by 4.8 For example, for model 1 in table 9, the probability of training of “technicians and mid-level professionals” before transition is 18.5 per cent higher than in "elementary occupations”. This difference is statistically significant. We analyse the results below.

The meaning of training before leaving an occupational category or after arriving at an occupational category has very different meanings that need to be laid out. When training after arriving in a new category, this training can usually be assumed to be paid by the new employer. These types of training tend to occur in highly skilled categories where investments in skills could be protected from intra-sector firm competition for talent. It is less likely to occur where sector or industry-specific skills prevail, and more likely to occur when firm-specific skills prevail. Consistently, training after transition is statistically significant – compared to transitioning into the baseline category – when transitioning into the category of scientific and intellectual professionals, or the category of officers, operators and craftsmen of mechanical arts and other trades, where specific skills are often needed (model 2).

Training before changing categories has more of an individual strategic component. This type of training is less likely to have been paid by firms. It may be part of a strategy oriented to self-employment. Consistently, table 6 shows the only transition that is associated with a training instance before changing jobs that is statistically significantly different from transitioning into the baseline category is transitioning into the category of technicians and mid-level professionals (model 1).

Significantly, from a substantive standpoint, for most categories, workers transitioning to a new category do not participate in training more often than workers transitioning to the category “elementary occupations”, a general skills-based category. This is consistent with the overall character of the labour market in Chile (and Latin America), where, except for a few categories, the labour force is low-skilled, and the labour market mostly requires general and soft skills. This is also consistent with the previously found small but positive effect of training in finding a job when unemployed.

Table 6: Training before and after moving jobs between occupations

|

Training before transition (1) |

Training after transition (2) |

|

|

Managers and directors |

-0.185 |

1.023 |

|

(-0.29) |

(1.29) |

|

|

Scientific and intellectual professionals |

0.630 |

1.154* |

|

(1.79) |

(2.31) |

|

|

Technicians and mid-level professionals |

0.739* |

0.297 |

|

(2.50) |

(0.81) |

|

|

Administrative support staff |

-0.242 |

0.325 |

|

(-0.68) |

(1.04) |

|

|

Farmers and skilled agricultural, forestry and fishing workers |

0.236 |

|

|

(0.35) |

||

|

Officers, operators and craftsmen of mechanical arts and other trades |

0.236 |

0.677* |

|

(0.65) |

(2.09) |

|

|

Plant and machine operators and assemblers |

0.591 |

0.330 |

|

(1.72) |

(0.86) |

|

|

Elementary occupations |

0.0869 |

|

|

(0.31) |

||

|

Age |

-0.00834 |

-0.0160 |

|

(-1.06) |

(-1.45) |

|

|

Female |

-0.0224 |

-0.124 |

|

(-0.13) |

(-0.54) |

|

|

Contract |

0.597* |

0.591 |

|

(2.15) |

(1.61) |

|

|

Mother's education: Primary |

-0.0875 |

1.147 |

|

(-0.20) |

(1.11) |

|

|

Mother's education: General secondary |

0.0366 |

1.255 |

|

(0.08) |

(1.21) |

|

|

Mother's education: Technical secondary |

-0.210 |

0.920 |

|

(-0.39) |

(0.82) |

|

|

Mother's education: Technical tertiary |

0.432 |

1.134 |

|

(0.79) |

(0.98) |

|

|

Mother's education: Tertiary university |

-0.637 |

1.950 |

|

(-0.94) |

(1.77) |

|

|

Constant |

-2.394*** |

-4.131*** |

|

(-3.64) |

(-3.43) |

|

|

Observations |

1,487 |

1,529 |

*

Conclusion

This article primarily explores the effect of training among the unemployed on their ability to achieve greater retention in jobs after returning to the labour market. We find there is a small but still significant positive effect of training, of about 4.3 to 4.5 percentage points, in reducing post-training unemployment events: roughly half a month by year. Then, for employed workers, we describe the incidence of training when workers change jobs between occupational categories. In line with the previous analysis, the picture portrayed suggests training occurs mostly among highly educated workers (professionals) or workers in occupations with high demand for specific skills (machine operators), which are hardly abundant in the Chilean or Latin American labour markets.

This overall picture is in line with previous knowledge of the region in terms of the scarcity of training, mostly because of a lack in demand for training. However, the moderate but positive results support the argument about the importance of lifelong learning and the need to focus on policy that increases the incidence of training in the labour market. While the likes of the labour market in Chile (and Latin America) suggests there are few incentives for firms to invest in training, there is also evidence about the importance of this kind of social investment for boosting not only job tenure but, in the medium term, productivity as well. This strengthens previous results in terms of active labour market policy highlighting the need to establish programmes with multiple objectives and interventions in order to improve the chances of success and avoid problems such as deadweight costs and/or creaming because of problems with targeting interventions (see ILO 2016). At the same time, it reinforced the need to take programme design into consideration, particularly the duration of training programmes, the input from employers to enhance matching between supply and demand of skills, as well as the importance of labour intermediation to overcome social capital problems among those most vulnerable.

Results are consistent with initial expectations drawn from the specialized literature, which tend to find moderate and short-term effects of training on employment indicators. Finding results that are consistent with the literature in a context of the low incidence of training could be seen as an important result speaking to state efforts in improving training policies oriented not only to employed individuals, where most of the training efforts are undertaken nowadays in Chile, but also for the unemployed (only 10 per cent of all training instances in our sample). Digitalization and the expansion of the internet network and technology should be identified by governments as powerful allies in expanding training opportunities for the unemployed. In markets such as in Chile, where long-term unemployment – and thus low levels of dynamism in the labour market – is moderately high, efficacy in training for the unemployed is an encouraging result. It suggests a growing importance of training policies in the future, particularly in the context of technological transformations that will bring additional challenges for long-standing social ills.

Annex

Table A1. Average effect of skills formation in transition from unemployment to employment, no year-fixed effects (robust standard errors and bootstrapped confidence intervals)

|

Model (5) Robust Std. Err. |

Model (6) Bootstrapped Conf. Int. |

|

|

Under treatment=1 |

-0.0488** |

-0.0488** |

|

(0.029) |

(0.019) |

|

|

Age |

0.035*** |

0.035*** |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Constant |

0.138 |

0.138 |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Year-fixed effects |

NO |

NO |

|

Observations |

11,012 |

11,012 |

*

References

Arulampalam, W. and Booth, A. L. 1998.

Baldwin, R. 2019.

Barro, R.J. and Lee, J. 2015.

Bogliaccini, J. A. and Madariaga, A. 2020. “Varieties of Skills Profiles in Latin America: A Reassessment of the Hierarchical Model of Capitalism”. Journal of Latin American Studies 52(3): 601–631.

Calderón-Madrid, A. 2006. Revisiting the Employability Effects of Training Programs for the Unemployed in Developing Countries (Working Paper No. R-522). Inter-American Development Bank.

CNP (Comisión Nacional de Productividad). 2018. Formación de competencias para el trabajo en Chile. Santiago: CNP.

Comisión Revisora del Sistema de Capacitación e Intermediación Laboral. 2011. Informe Final - Comisión Revisora del Sistema de Capacitación e Intermediación Laboral. Available at: https://www.cl.undp.org/content/chile/es/home/library/poverty/informes_de_comisiones/informe-final-comision-revisora-del-sistema-de-capacitacion-e-in.html

Comyn, P. and Brewer, L. 2018.

Contreras, D

Crépon, B., Ferracci, M. and Fougère, D. 2007.

de Chaisemartin, C. and D’Haultfœuille, X. 2020. “Two-Way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects”.

Dixon, S. and Crichton, S. 2006.

Egaña del Sol, P. and Joyce, C. 2020. “The Future of Work in Developing Economies”.

Estevez-Abe, M. 2005. “Gender Bias in Skills and Social Policies: The Varieties of Capitalism Perspective on Sex Segregation”.

Estevez-Abe, M. 2009. “Gender, Inequality, and Capitalism: The “Varieties of Capitalism” and Women”.

Fitzenberger, B., Osikominu, A. and Paul, M. 2010.

Fouarge, D. and Schils, T. 2009. The Effect of Early Retirement Incentives on the Training Participation of Older Workers.

Frey, C.B. 2020.

Gelman, A. and J. Hill. 2007.

Goldin, C. D. and Katz, L. F. 2008.

Hanushek E.A. and Woessmann, L. 2015.

Hirshleifer, S.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2015.

—. 2016.

—. 2017.

Iversen, T. and Soskice, D. 2001. “An Asset Theory of Social Policy Preferences”.

James, L., Guile, D. and Unwin, L. 2013. “Learning and innovation in the knowledge-based economy: beyond clusters and qualifications”.

Kalleberg, A. L. 2009. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition”.

Leuven, E. 2005. “The Economics of Private Sector Training: A Survey of the Literature”.

Lindemann, K. and Gangl, M. 2019. “Parental Unemployment and the Transition to Vocational Training in Germany: Interaction of Household and Regional Sources of Disadvantage”.

Livingstone, D. W. 1999. “Lifelong Learning and Underemployment in the Knowledge Society: A North American perspective”.

Long, J. S. 1997. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables (Vol. 7). Sage Publications.

Richardson, K. and van den Berg, G. J. 2002. “The Effects of Vocational Employment Training on the Individual Transition Rate from Unemployment to Work”. Swedish Economic Policy Review 8(2): 175–213.

Roth, J. 2019. Pre-test with Caution: Event-study Estimates After Testing for Parallel Trends. Department of Economics, Harvard University (unpublished manuscript).

Smyth, E. 2018. “Gender and school‐to‐work transitions research”, in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. John Wiley & Sons: 1–14.

Taylor, B. 2011. “Hire for Attitude, Train for Skill”. Harvard Business Review, February 2011.

Veinstein, M. and Sirdey, I. 2016. “Vocational training: a transition towards the employment of young job seekers in Brussels with limited education?” Brussels Studies (96): 1–11.

Wilson, T. 2013. Youth unemployment: Review of training for young people with low qualifications. Government of the United Kingdom, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

World Bank. 2019. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Acknowledgements

We thank Janine Berg, Hannah Liepmann and Emiliano Tealde for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on the preliminary versions of the models and paper. We also thank Pizarro Schkolnik for his incredible help in transforming the original dataset into a workable panel structure. Finally, we also thank two kind anonymous reviewers at the ILO for their comments. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this article rests solely with its authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in it.