Key workers in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

This study analyses the experience of key workers in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic. It analyses their working conditions prior to the pandemic, and then assesses how the pandemic heightened their job demands. In addition, it assesses the extent to which the State and private employers provided the requisite job resources to enable them to cope with the increased demands caused by the crisis. The study finds that some frontline workers have had an increase in work pressure, while other categories of workers, particularly in the informal economy, experienced a decrease in work pressure as demand for their services fell off given the general declines

Introduction

Since its onset in early 2020, the coronavirus pandemic has been a daunting challenge for governments, who have had to struggle to contain the health crisis while at the same time, keeping the economy afloat. The balance

In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the ILO (2020) found that the pandemic has had a harmful effect on 83 per cent of its informal workers. In addition, compliance with COVID-19 health and sanitation protocols was difficult, particularly in countries with pre-existing weak socioeconomic structures. Nonetheless, many countries in the global South, such as Ghana, adopted and domesticated COVID-19 advisories from global bodies

The pandemic also highlighted the importance of certain categories of workers, whose jobs previously did not command much respect. The portrayal of some categories of workers as “essential workers” was an acknowledgement of the crucial role that workers in some sectors of the economy play in our daily survival. This category of workers was granted mobility exemptions during the lockdown period and in some jurisdictions received financial support for the risks they faced in performing their jobs during the period. In Ghana, a narrower category of essential workers in the health sector was created and provided additional financial support. These workers known as “frontline workers” were health workers who had been involved in the management of a confirmed case of COVID-19.2

The disruptions wrought by the pandemic have resulted in massive job losses globally and even for those who did not lose their jobs, the traditional workspace has been modified to accommodate the realities of a pandemic. Workers have had to adjust to new ways of working through enhanced digitalization, space readjustments, among others. The ILO (2021) has explored the changing nature of work, its implications for workers and the myriad responses of states, employers, and worker organizations to these changes. This report seeks to add to that body of work. It is a three-pronged effort in understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on “essential” or “key” workers in Ghana. It begins with an understanding of working conditions pre COVID-19, then it provides insights on ways in which the pandemic heightened the job demands of essential workers in Ghana and the extent to which the State and private employers provided the requisite job resources to enable employees to cope with the increased job demands emanating from the crisis, and finally in the third part of the analysis, we explore the hopes these workers have for a post COVID-19 future.

Ghana’s first two cases of COVID-19 were detected on 12 March 2020. The WHO reported that as of 10 December 2021 there were 131,246 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 1,228 deaths in Ghana.3 Although Ghana’s COVID-19 cases were relatively low overall, this could not have been known at the onset of the pandemic. The government thus responded rather swiftly to the first two detected cases and imposed a series of severe containment measures. This included: nine months of school closures; air and land border closures (the land border remained closed while air borders reopened in September 2020); a ban on public gatherings for social activities, such as festivals, workshops, conferences, concerts, political rallies, church activities and rites of passage (weddings and funerals); and the imposition of a rotational system in the country’s many open-air markets. A three-week lockdown was also imposed on Accra and its environs of Tema and Kasoa, as well as in Kumasi, the second largest city.

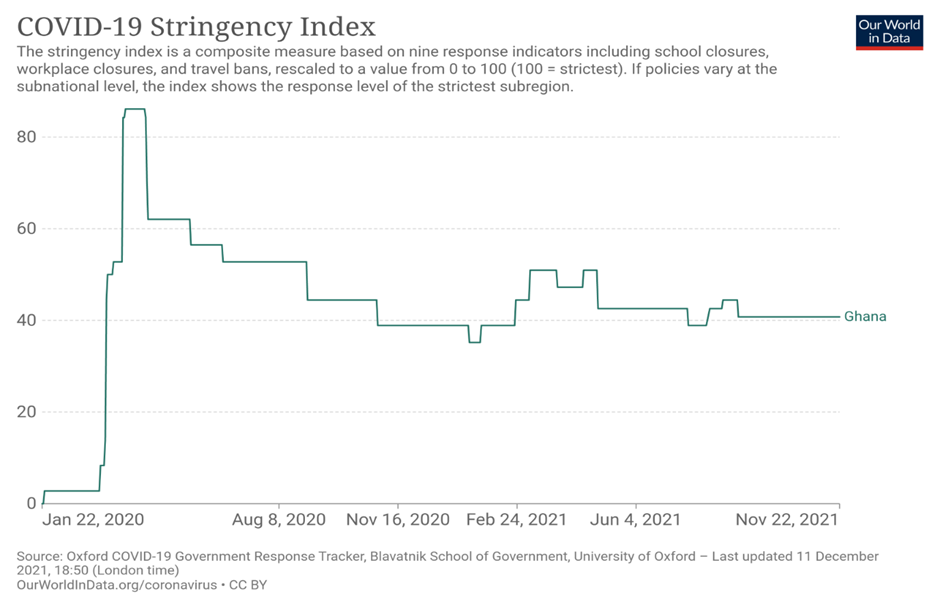

By May 2020 the restrictions were slowly easing, hotels, bars and restaurants were allowed to open with social distancing protocols in place. Churches also reopened with stringent safety protocols, including registration and a limit on the number of people and time spent in church. All other large gatherings that drew more than a hundred people continued to be banned. As evident in Figure 1, in March 2020 Ghana’s COVID-19 Stringency Index was roughly 85 but this eased somewhat two months later and considerably six months later to 45. Soon after the New Year 2021, in the wake of a second wave of the pandemic, the government imposed a new set of restrictions, but this time they were nowhere as severe as those imposed in the first few weeks after the first case was identified. By November 2021, Ghana’s Stringency Index stood at 40.74 which was half of what it was at the beginning of the pandemic.

Figure 1: The stringency of Ghana’s COVID-19 measures from January 2020 to November 2021

The high stringency measures of the first two months of the pandemic in Ghana (March and April 2020) as opposed to the rest of the months since then is detailed in Figure 2. As evident in Figure 2, in the first two weeks after the first case was identified in Ghana, the Ghanaian government instituted six different public health measures designed to curb the spread of the pandemic. By May, however, the public health measures that were introduced eased the restrictions that had been imposed on the population in the previous months. In place of a complete closure or ban on a range of activities, instead they could take place but with guidelines that included social distancing and caps on the number of people or hours that an activity could take place.

By the time the first wave hit in July 2020, most of the restrictions of the first few weeks of the pandemic had been reduced and by January 2021 when the second wave hit, although some new restrictions were put in place, it was clear that the State was seeking to return the populace to life as usual, as fast as possible – witness the fact that all public schools, including universities, were reopened at the height of the second wave of the pandemic.4 The stark difference between the restrictions associated with the immediate arrival of the pandemic and those associated with the second and third wave was evident in the decline in the frequency of presidential statements to the citizenry. This Sunday evening event was so frequent in 2020 that a Ghanaian fabric was designed and named “Fellow Ghanaians”, which was the refrain with which the President of Ghana started each of his COVID-19 updates.5 Between 12 March 2020, when the first case was detected, and 17 January 2021 when the President announced the beginning of the second wave, the President delivered 22 of these updates. Between 17 January and 15 December 2021 only five speeches were delivered.6

Figure 2: Measures implemented by the Ghanaian government in the first four months of the pandemic

Source: Zhang et al. 2020 https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/28/how-well-is-ghana-with-one-of-the-best-testing-capacities-in-africa-responding-to-covid-19/

The pandemic and the attendant state-imposed containment measures have had a disastrous impact on the Ghanaian population. In a survey conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) six months into the pandemic, it was noted that approximately three-quarters (77.7 per cent) of Ghanaian households, representing 22 million Ghanaians, had experienced a decrease in income since mid-March 2020 (GSS 2020a, 1). To survive the negative impact of the pandemic, roughly half (52.1 per cent) of households reduced their food intake (GSS 2020a, 1).

Workers in Ghana’s formal economy, representing 28.7 per cent of the working population according to the Ghana Living Standards Survey of 2016/2017 (GSS 2019, 74), were the ones most likely to have been able to withstand the economic shocks wrought by the pandemic. Those working in the private, formal economy, who were able to adopt online tools for work purposes, transitioned relatively smoothly to an online working environment during the period. Workers in the public sector were also likely to retain their jobs. For example, although schools were closed for nine months, teachers in public schools continued to receive their salaries. However, teachers who worked in private schools were not so lucky. Some lost their jobs while others had to cope with slashed incomes. The government announced a 50 million Ghanaian cedi (GH¢) relief package for private schools in September 2020,7 some of which was hopefully spent on paying the salaries of these teachers. Workers in other sectors, such as the hospitality and tourism industries,

Workers in the informal economy comprising own account workers, workers in informal enterprises, informal workers in formal enterprises and informal work and production for household consumption (Schwettmann 2020) have been hit hard by the pandemic (ILO, 2020). While Ghana’s Labour Act is encompassing and excludes few dependent workers from coverage of its labour protections, in practice, the rights and benefits of labour law in Ghana are not applied. In addition, a large percentage of the labour force is self-employed and thus without the legal rights and benefits that come from an employment relationship. As such, these “informal” workers were without necessary protections when the pandemic hit, and their plight is illustrative of the ways in which the pandemic affected the vulnerable in society.

While the vulnerability of most informal workers has worsened as a result of the pandemic, a small segment of workers in the formal economy, specifically trained nurses, have seen a relative improvement in their circumstances during the pandemic. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many trained nurses had difficulty securing stable employment. Many had been unemployed for years, prompting demonstrations. Indeed, the situation was so dire that a Graduate Unemployed Nurses and Midwives Association with a membership of over 40,000 individuals was created.8 The pandemic changed that situation. To boost the low patient-health worker ratio in the country to tackle the COVID-19 threat, 65,000 health personnel, considered essential workers, were employed to help address the pandemic.9 The exact terms and conditions of their employment were, however, unclear. Although it was in the news that contact tracers were to be paid a daily rate of roughly US$25, other news reports suggested that this was not paid regularly. A second issue was whether their temporary jobs would be converted into permanent jobs in the health sector once the pandemic was over.

For manufacturers of healthcare items such as medicines, hand sanitizers and personal protective equipment (PPE), the pandemic provided a unique opportunity to expand their business, with some even getting state support for that purpose.10 Four such companies received a grant sum of US$10 million from the Ghanaian government in April 2020 to produce PPE.11 In fact, even small scale entrepreneurs who had the requisite training and skills turned to this sector to be able to make a living during the pandemic. The well-known entrepreneur, Mabel Simpson, known for her beautiful Afrocentric handcrafted bags and laptops, started making face masks during this period. Some scholars, such as Mugisha (2020), have gone as far as to suggest that the numerous companies who rose to the challenge during the pandemic to produce the many items the country would otherwise have imported, would be the fulcrum around which Ghana’s industrialization drive might revolve. While it is true that some local companies produced an impressive range of items over the last eighteen months, it was very doubtful that this would fundamentally shift Ghana’s dependence on imports.

The workers hardest hit by the pandemic were those in the informal economy who represent the largest proportion of workers in Ghana. Ghana’s Living Standards Survey 2016/2017 showed that 71.3 per cent of economically active people were in the informal economy (GSS 2019: 74). Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) conducted some surveys that provided insight into the impact of the

Other surveys also provided insight into the ways in which the world of work in Ghana in general has changed over the course of the pandemic. One such representative survey was conducted by Ghana’s Statistical Service with financial support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank. That survey of 4,311 firms between 26 May and 17 June 2020 indicated that 25.7 per cent of the workforce (about 770,000 workers) had their wages reduced while 1.4 per cent (about 42,000 employees) lost their jobs. Firm owners predicted that if the economic conditions did not improve, 15 per cent of workers could eventually lose their jobs (GSS 2020b, 1). In November 2020, the second wave of the same survey in the agribusiness sector was conducted. The evidence showed that 16,091 agribusiness firms representing 11.6 per cent of all such firms remained closed even though the lockdown had been lifted for more than six months at that point (GSS 2021, 4).

In recognition of the economic difficulties facing the country, the government expanded some of the pre-existing social protection programmes targeted at specific segments of the population and introduced some subsidies targeted at the entire population. Since 2008, the State has been running a social security programme for poorer households, known as the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) programme. The programme covers selected households with social groups such as Orphaned and Vulnerable Children (OVC), persons with severe disability without any productive capacity, extremely poor pregnant women, and elderly persons who are 65 years and above. In 2016, 213,044 households across the country benefitted from the programme. It provided cash transfers and health insurance to the beneficiary households. Before the onset of the pandemic, the beneficiaries received between GH¢32 (approximately US$5.50) and GH¢54 (US$9) monthly which was disbursed quarterly. To cushion the beneficiary households against the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic, the payment process was quickened, and households received payments in advance. The beneficiaries also received an additional sum of money to enable them to purchase PPE.12 In addition, to reduce the face-to-face contact with beneficiaries, an E-zwich electronic platform, was introduced to transfer the money directly to the beneficiaries.13

There were universal subsidies for water and electricity. For the months of April, May and June 2020, the government provided rebates on these two services. Free electricity was provided for those described as “lifeline consumers”, that is those who consume less than 50kwh per month while those who consume more than 50kwh received a 50 per cent rebate. Water was provided free to all citizens to ensure that there were no financial disincentives to adhering to the hand washing safety protocols. The free access to water offer was eventually extended to December 202014 while electricity was extended to September 2020.

However, the lack of universal access to basic services, such as pipe borne water and electricity, undermined the effectiveness of these State subsidies. Oduro and Tsikata (2020, 31) pointed out that 50 per cent of Ghana’s population did not have access to pipe borne water, a situation that was more acute in rural Ghana. Even in urban Ghana, wealthier homes are more likely to have access to pipe borne water than poorer homes. Thus, the benefits of the State subsidy on water accrued much more to the rich than to the poor. A similar story can be told for the electricity subsidy. Given that access to electricity was much better than access to water, data from the Ghana Statistical Service shows that while only 22 per cent of Ghanaians benefitted from the subsidies on water, 75 per cent benefitted from the electricity subsidies (GSS 2020c, 1).

The State also announced a number of tax waivers in 2020 to help ease the financial burden caused by the pandemic. The communication tax was reduced from 9 per cent to 5 per cent and workers were allowed to withdraw from their provident funds without paying a penalty. In 2021, however, to reclaim some of the losses the State incurred the previous year, a new set of taxes was introduced even as the waivers of 2020 reached their expiration. As at the end of 2021, citizens were paying GH¢0.20 per litre of petroleum/diesel and GH¢0.18 per kilogram of Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) as part of the Energy Sector Levy (Amendment) Act 2021, (Act 1064). In addition, the Sanitation and Pollution Levy required citizens to pay GH¢0.10 per litre of petrol and diesel. These two new taxes increased fuel prices and by extension transport costs. Food items which were transported across the country at a higher cost have thus gone up as well.

For the approximately 7,000 healthcare personnel in the public sector designated as frontline workers, that is those likely to manage an identified COVID-19 patient, the State introduced a few financial incentives soon after the onset of the pandemic. This included the provision of insurance coverage amounting to GH¢350,000 (approximately US$60,000) per person, tax exemptions for three months as well as a 50 per cent increase in their basic salary for a period of four months.15 During the three-week lockdown, the State also provided free transportation for these frontline workers.

Another group of workers considered as key workers during the lockdown were the market traders and street traders. Given that they were mostly providing food and other essentials, they were technically supposed to be allowed to work during the lockdown. Studies showed, however, that this was not always the case and that they were subjected to harassment from security personnel during the period of the lockdown (WIEGO 2021).

This report builds on these studies and provides insight into the experiences of key workers in Ghana during the period of the lockdown. Our categorization of key workers drew on the Ghanaian State’s definition and includes healthcare workers, street traders, as well as transport workers. For our purposes, we also include workers in educational institutions, specifically nursery teachers who were exempted from the categorization of key workers.16 To make sense of the data, we drew on Bakker and Demerouti’s (2007) job demands-resources model as an analytic framework. In this model, Bakker and Demerouti (2007) argue that in an ideal world, there would be a positive relationship between job demands and job resources. In other words, a work environment that makes huge demands on employees would provide the equivalent job resources to make it possible for the workers to deliver on these demands. However, as is often the case in low-income environments, there are situations where high job demands are not matched with high job resources. Using this framework, we interrogated the extent to which the pandemic placed higher job demands on employees, exploring how this was or was not matched with the requisite job resources, as well as exploring what hopes workers hold for a post COVID-19 world. In exploring job demands, we drew on Bakker and Demerouti’s (2007, 312) examples of “work pressure, an unfavourable physical environment, and emotional interactions with clients” as a guide. We defined work pressure in two ways; the pressure at work as well as work-life balance. Similarly, in assessing job resources, we turned to Bakker and Demerouti (2007, 312, 313) and looked:

at the level of the organization at large (e.g., pay, career opportunities, job security), the interpersonal and social relations (e.g. supervisor and co-worker support, team climate), the organization of work (e.g. role clarity, participation in decision making), and at the level of the task (e.g. skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, performance feedback).

The job demands-resources framework shares similarities with the ILO’s concept of decent work.17 However, they are distinct in a significant way. While the job demands-resources framework concerns the immediate work environment, the ILO’s concept of decent work encompasses societal level concerns, such as the abolition of forced labour and child labour and the rights of non-discrimination and freedom of association and collective bargaining rights. Nevertheless, there is some overlap. The component of job resources at the level of the organization, specifically pay, shares similarities with the decent work indicator of adequate earnings. Similarly, job demands such as an unfavourable physical environment shares much in common with the decent work indicator of a safe work environment. We use this framework fully cognizant of its limitations. First, this framework takes certain resources for granted, specifically the State resources, be it law or social protection schemes that enable workers to interact with clients, particularly low-income clients with a certain level of assurance that they are not constrained by the lack of financial resources. In countries of the global North, where a welfare state can be taken for granted, an employee in a health institution for example can go out of their way to provide services for an otherwise impoverished client, knowing full well that once the requisite paperwork has been filled out, there would be state resources to cover the cost, for example, of a hospital stay including medication. Health personnel in Ghana did not work with such an assurance. We, thus, explore the implications of the lack of such resources for the work environment. Secondly, the framework was designed for understanding firms functioning with some sense of normality. It did not make room for the kind of shocks to the world of work that COVID-19 wrought. To account for this, we included an extra dimension to job resources at the organizational level that focused on what we called safety protocols and asked to what extent the work environment was reconfigured (through the provision of PPE, adherence to hand washing and social distancing rules) to accommodate the pandemic.

Research methodology and workers/small business owners interviewed

A qualitative methodological approach was adopted for this research project because of the interest in understanding individual’s experiences with COVID-19. In-depth interviews were conducted between 9 July and 28 August 2021. Most of the interviews were conducted in the language the interviewee was most comfortable (Twi and Ewe) with a few of them conducted in English. The recorded interviews were then translated into English if necessary and all interviews transcribed and analysed using the computer assisted data analysis software Nvivo. A total of 50 individuals were interviewed (37 were employees, nine were employers and four were own account workers) and to ensure confidentiality and anonymity, we used pseudonyms instead of the real names of participants. All interviewees worked in areas that have been classified as essential services either in Ghana18 or elsewhere in the world, specifically education, health, food services and transportation (see Table 1).

In sampling, we used our personal contacts to reach some teachers, nurses, traders, and dispatch riders, later this expanded to reach more workers in these sectors. Tro-tro mates19 were, however, selected from the main tro-tro station at Madina Market. We selected tro-tro mates who travelled on long distance journeys and those who worked within Accra. We also took into consideration the two groups of commercial tro-tros in the country - those who belong to the transport union (the Ghana Private Road Transport Union) and had a fixed station and those who did not have a fixed station and are often referred to as “floaters”. These groups, although engaged in the same activity, experienced the pandemic differently. Similarly, traders were selected based on the items they sold. Thus, we focused on traders who sold food and other essential household items.

Table 1: Occupations and employment status of interviewees

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education |

Nursery/Kindergarten school Teachers |

Employee |

5 Females |

|

Food and other household essentials |

Food Vendors |

Employee |

1 Female; 1 Male |

|

Business owner |

5 Females |

||

|

Street Traders |

Employees |

1 Female; 1 Male |

|

|

Business owner |

4 Females; 1 Male |

||

|

Health |

Environmental Health Officer |

Employee |

1 Male |

|

Mortuary Attendants |

5 Males |

||

|

Nurses |

5 Females |

||

|

Orderlies |

4 Females; 1 Male |

||

|

Medical Counter Assistants |

3 Females; 2 Males |

||

|

Transport and dispatch riders |

Dispatch riders |

Employee |

2 Males |

|

Business owner |

3 Male |

||

|

Tro-tro mates |

Employee |

5 Males |

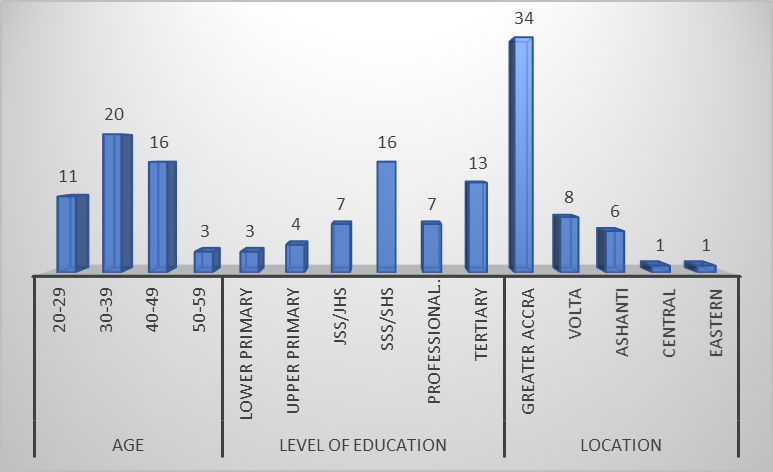

The Greater Accra Region of Ghana, in which the capital city is located, has been the region hardest hit by the pandemic. It recorded two-thirds of the total number of Covid cases in the country.20 As the epicentre, it was the only region that experienced the lockdown along with its neighbouring city of Kasoa and the second largest city, Kumasi. Residents in the other regions were not spared the ravages of the pandemic nor the ripple effects of the government’s containment measures. For example, the restrictions on gatherings in the two largest cities, with the largest populations and income earners, affected food system businesses and workers (farmers, transporters, traders) far removed from these cities. A decrease in gatherings meant fewer purchases of the food items supplied from Ghana’s hinterland. Although most of our respondents were drawn from the Greater Accra Region and the two locations included in the lockdown restrictions (six from Kumasi in the Ashanti Region and one from Kasoa in the Central Region), we also included one respondent from a town in the Eastern Region and eight from other towns in the Volta Region. Of the 50 respondents: one was Nigerian (the only non-Ghanaian); their ages ranged from 20 to 59 years; 23 were married and 24 were single; three respondents were cohabiting, widowed, or divorced. In terms of education, one third had completed primary education, one third secondary education and one third tertiary education (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Socio-demographic characteristics of research participants

Source: Author based on interviews.

Results

2.1 Job quality of workers prior to the pandemic

Workers across the sectors studied expressed various ways in which their work was precarious prior to COVID-19. Drawing on Bakker and Demerouti (2007), we began with an exploration of the three dimensions of job demands prior to the pandemic: emotional interactions with clients; unfavourable physical environment; and, finally, work pressure. Then we turned to an analysis of these issues during the pandemic.

2.1.1 Job Demands prior to the pandemic

In describing job demands respondents focused largely on work pressure, making only a few references to the emotional interactions with clients and an unfavourable physical environment.

With respect to emotional interactions with clients, a few respondents pointed out that this was sometimes difficult because clients disrespected them. Nancy, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Physician Assistantship but worked as a medical counter assistant, was the one respondent who best highlighted the disrespect employees encountered. In her case, she believed she was disrespected because she was female. She noted:

-

-

Sometimes it is annoying, the way some of them talk to us alone, it is something else. And then, especially with me, they do not know my qualifications. Some people will come, and they will talk as if I am a nobody and I am like ‘Ok, wow.’…. They undermine me because I am a woman. They talk to me anyhow they please because -- because I have realized instances where I have been there with a male colleague and customers come in and then the way they talk to him -- because he is a man, the way they talk to him is different from when I am alone, and I am a woman and then they are talking to me. Some people want to look down on me because I am a woman. They think I do not have enough knowledge and all that.

-

Other medical counter assistants described their emotional interactions with clients not in terms of the disrespect they endured, but in terms of the demands it made on them financially. Here, the lack of social protection services for low-income individuals in Ghana became abundantly clear. In the absence of state support, citizens were by default the state, sometimes at great financial cost. Some of these relationships were episodic, others more permanent. Nadia, a medical counter assistant, described her episodic acts of Good Samaritanism casually as follows, “Some are abused by their husbands, and they come and do not even have money to buy medicine. Sometimes, we give medication to clients for free and pay from our own pockets.” Phillip, another medical counter assistant, described his more permanent relationship with several indigent, older clients in the following words:

-

-

At times when the aged come with their prescriptions, they lament they don’t have money, and no one is taking care of them, so emotionally, I get touched. Currently I am taking care of the medical bills of two aged patients with my own earnings and even to the extent of feeding them.

-

Interestingly, although food vendors were yet another category of worker providing the basics for survival, none of those interviewed discussed having a set of customers they routinely served for free. This kind of emotional interaction with clients was only found among the medical counter assistants we interviewed.

With regards to the second dimension of job demands, the nature of the work environment, of the traders and health workers interviewed, it was the former more so than the latter who complained about the safety and health hazards of their working environments. Both employers and employees who worked as traders complained about the nature of the work environment. This included Mabel, an employer who complained about the extreme heat in her kitchen and in the case of Akoto, an employee, the lack of equipment to carry goods had led to his back problems. Julie, a self-employed food vendor, also noted “I do not often fall sick but the problem I have is that I mostly feel aches in my legs due to me standing for long periods of time. It makes the muscles in my legs tense.” Akua, a street trader with two employees, complained about the stench in her shop which emanated from the gutter right in front of her shop that carried all manner of liquid waste from the market. Among the group of health workers interviewed, the complaint about the work environment came from the mortuary attendants who talked about the strong stench of the chemicals they used in their line of work, especially the formalin.

By far the most common theme that ran through our interviews with respondents in terms of job demands was the pressure at work as well as the pressure of the daily grind. In some workspaces there were too few employees which meant they worked without a break. Nancy, a medical counter assistant, who singlehandedly managed a pharmacy shop, described a typical workday in the following words “because I am there alone, sometimes I even go hungry. Because when I get there in the pharmacy, once I step out, someone will come so I do not have to leave for management to lose that money. So sometimes I go hungry.” Eli, a hospital orderly opined,

-

-

The workload in our ward shouldn’t be for one person or two and the worst is that if the superiors come around and see a little dirt somewhere, they would be questioning my effectiveness as an orderly. There are times that I get dizzy when I am working due to the workload. It is not easy at all.

-

The tro-tro mates reported having a break routinely during the day. Dan explained,

-

-

We always go on break each day. It is often in the afternoon when business is a bit slow because children are in school, traders are in the market and people are at work …. we can relax for about two to three hours

-

In terms of the third dimension of work pressure which we defined as the extent to which the long hours at work or lack of control over hours affected work-life balance, only the teachers interviewed did not seem to have much of a complaint. They worked a forty-hour week and had weekends off. For the most part they had a good work-life balance; they could attend social events if they so desired, many of which were organised on weekends in Ghana. Emefa, a nursery teacher said, “Yes I am able to attend social gatherings.” However, that depended on whether work activities had not worn them out during the week. Yaa, another nursery teacher pointed out, “If I am tired, I don’t make it at all.” For other nursery teachers, the weekends were reserved for house chores – shopping, cooking, cleaning and could not be spent at social gatherings. Enyonam said, “during the weekends, there are a lot of things for me to do at home. So, I can’t leave what I want to do and then attend that programme [a wedding or funeral] as well…. So, I don’t get the chance to go out, join friends and have fun. No.”

The other workers were not so lucky. Many of them spoke about not having a good work-life balance. Nadia, a medical counter assistant in a private pharmacy, had not been able to visit her parents for two years. Kojo, a mortuary attendant, described his lack of control over his work hours which made it difficult for him to attend family gatherings, here is what he said:

-

-

I don’t get the time to attend such social gatherings and commitments. I have already explained to them the nature of my work and so they are aware of it. So, what I usually do is to send money to be used for those commitments…. I am responsible for burying all the dead bodies of Otumfuo Osei Tutu II [the King of the Ashanti Kingdom] and so no matter where I am, when they have a funeral, I must show up.

-

The self-employed delivery servicemen21 in particular, had a personal dilemma. Their hours were not fixed but depended on whether they had an order or not. When an order came through, they risked losing a client if they refused to honour it on account of needing a break. Emmanuel explained,

-

-

Ok there is an order coming in, I have to go and pick it up immediately, I will earn this much. If I don’t do it, I will lose the customer. Then, if I lose the customer, he or she is not going to call me again. You know, that is one thing that pushes us to keep working.

-

The employees also risked losing income if they took time off for family events. Akoto, who worked for a food vendor, explained as follows,

-

-

You see, I am not paid monthly like other employees in other sectors and so I can attend whatever event I please. I just inform my boss and leave for that event. But I will not be paid for the days that I will be absent.

-

Employers with multiple employees such as Adwoa, a food vendor, were the ones who had an easier time managing their work-life balance; they could delegate to a responsible employee and take time off. As she put it,

-

-

when I must attend a funeral, I come here early in the morning to cook the food that will be sold for the day, and I leave it for my girls to manage the place while I attend the funeral. I then come back here after the funeral.

-

Similarly, Oye, a food vendor with ten employees, said,

-

-

But when I have an event such as a wedding to attend on a Saturday, I will still come to work and supervise the preparation of the food and ensure that everything is in order before I leave.

-

This requires a certain level of trust that employees would do right by the employer in the absence of the employer. Fred, the owner of a street shop, hinted at this in the following remarks:

-

-

Oh, you see, we have systems in place to monitor everything that goes on in here. We have CCTV cameras in the shop, and it captures everything that goes on in the shop. So, I can go wherever for as long as I want to. All I must do when I get back is just to take the CCTV footage, play back and I will be abreast with whatever happened in my absence. Moreover, we have computerized everything so I can just check the system and know how much was sold in my absence. So, it is not a problem for me to leave the shop and attend to personal emergencies.

-

Fred’s use of technology showed how it could ease the pressure of work. It is important to point out though that Fred was the only one we interviewed who talked about the use of surveillance technology in his workplace. These are expensive items that not many of these employers could afford. In the case of Akua, an employer with two employees, her distrust meant that she operated much like an own account worker; she could only attend a social event if one of her children in the university could mind the stall in her absence.

Overall, prior to the pandemic, the pressure of work, particularly the difficulties in establishing a good work-life balance, was the paramount issue of concern for all the workers. The only group of workers interviewed who were relatively spared this were the nursery school teachers.

2.1.2 Job resources prior to the pandemic

Given such heavy demands of work then, Bakker and Demerouti (2007, 312, 313) argued that the right amount of job resources was important to motivate workers. Our respondents highlighted three key elements of job resources: interpersonal social relations (such as supervisor and co-worker support), organization of work (such as role clarity and participation in decision-making) as well as organizational level resources (such as pay, career opportunities and job security).

In the health setting in particular, the orderlies highlighted the educational disparities among the hospital staff and the extent to which it undermined interpersonal and social relations in the hospital.

-

-

some orderlies are even smarter than these people who harass us, but we didn’t get the opportunity that they had. They got good opportunities and that is why they are occupying the positions they have today, but they don’t consider that. An orderly and someone who wears white [doctors], are they the same? No, they are not equal. They talk to us in a demeaning manner but what can we do about it?

-

In other work environments where most individuals, both employers and employees, were not likely to have tertiary education, there was much more of a cordial relationship between staff. Fred, the owner of a street shop, described the work atmosphere in his shop in the following manner, “It is difficult to differentiate between the owner and the employees as all hands are on deck when it is time to off load goods from the truck into the warehouse or arrange items on the shelf.”

Another element of interpersonal and social relations was the support supervisors gave to co-workers. This was a much more common theme for the health-sector workers, some of whom worked long hours, such as the medical counter assistants, or worked on weekends, such as hospital orderlies. In some cases, there was a formal system of swapping, where supervisors made it possible for their co-workers to shift their schedules around when necessary. When such a formal system of swapping was lacking, the workers devised informal mechanisms to address the situation. As Afriyie, a hospital orderly, explained, “I can only attend such events if I pay someone to do my work for me while I am away. For instance, I have funerals to attend today in my hometown, so I paid someone to do my job for me.” Others such as Kojo, the mortuary attendant who was personally responsible for burying anybody who died in the Ashanti king’s palace, had no such luxury. He forfeited a social event if it clashed with his work demands.

One mortuary attendant spoke about job resources with respect to the organization of work. Bright pointed out the lack of role clarity at his place of work in the following words:

-

-

There are mortuary workers but because the orderlies are not many, they use us to do the cleaning instead of getting more orderlies to do the job. They said they don’t want to employ a lot of people, but they need to…if there are more orderlies available, we the mortuary staff will also do our work without any interruptions and not this mortuary/cleaning appointment.

-

In discussing the job resources that motivated workers to give their best despite the demands of the job, it soon became clear that for many respondents, job resources at the organizational level, particularly with respect to pay, was poor. Income levels in Ghana are indeed low and the refrain ‘we are managing’ was a common one heard particularly from the health sector workers. Aboagye, a mortuary attendant, described the low earnings of workers vis-à-vis their skills in the following words:

-

-

Hmm, it's an issue. The salary and the skills are not equal. To be honest and fair with you, the salary isn't enough, but it is difficult to find another job, so we just accept this one as it is. The salary we are supposed to be earning is not what we are being paid. Although the payment is from the government, it is not enough. We are just managing the situation.

-

Kojo, yet another mortuary attendant, shared a similar opinion. He opined, “If we are to consider the work I do in this facility to the salary I receive, you’d agree it is an insult to me.”

-

-

For the salary, let's not talk about it because the government just added 4 per cent to our salary. Compare that to the increases in fuel, water bill, light bill, and school fees…. I'm left with about 10 years to go on retirement, I’m thinking about my retirement plan, I need to get a place like a house for my family, but things are not going as expected. Sometimes, it can affect our mental health.22

-

The nurses’ situation was no different. Rejoice, who worked as a public nurse, said, “even if I go on leave, the money I am receiving is not enough to cater for my responsibilities much less plan for a vacation or anything.” The nursery school teachers’ opinions were no different from that of the health professionals. Given their qualifications, two of the five nursery school teachers we spoke to believed they should be paid GH¢1500 (roughly US$250) a month. Neither of them received anything close to this amount. Emefa, who taught in a public nursery school but was not on the government payroll, received GH¢200 a month and Yaa, who taught in a private facility, received GH¢650 a month.

The traders in particular described not just earnings but other allowances they got at work. Mabel, a food vendor with employees, in describing the earnings of her employee said, “aside their daily allowance, I also provide them with accommodation, and, in my house, they use water, electricity and everything else for free, even feeding, but then sometimes they feed themselves.” Aisha, an employee for a food vendor, confirmed that she also got a similar range of benefits from her employer. She noted: “Yes, we eat whatever we want to eat, and it is free. She doesn’t stop us from eating the food we sell here. We eat 3 times in a day. We also have accommodation, water, and light for free. She provides all of that to us for free.”

In terms of earnings, the traders and transporters seemed better off than in particular the nursery school teachers. In fact, Nat, a tro-tro mate, summarized the situation as follows: “I am of the view that daily wage work is better compared to monthly salaried work,” Joyce, a street trader, said of her earnings, “The demand of the job matches the salary I get. My boss sees to it that she gives me a salary that will cater for the stress that comes with the job. So, I will say my salary is okay.” A comparison of earnings supports Nat and Joyce’s views. Nat said:

-

-

A mason is given a daily wage of GH¢90 and compared to a teacher or a banker, the mason would earn more than them at the end of the month. Initially we were paid a daily wage of GH¢25 but now it has been increased; it is on our worst days that we receive GH¢25. Now I receive GH¢30 per day aside the money I am given GH¢5 for food and so comparing that to someone who is a salaried worker earning GH¢600 per month, I think I earn more. So, I would say when it comes to wages, our work is slightly better.

-

Nat, the tro-tro mate, earned almost as much as Yaa and three times more than Emefa, both of whom earned monthly salaries as nursery school teachers.23

2.2 Experience of workers/small business owners during the pandemic

In exploring the world of work during COVID-19, we began with an exploration of workers in the health and teaching sectors, we explored the ways in which their job demands increased, if any, as well as the extent to which job resources matched job demands. In particular, in keeping with our expansion of the job resources at the organizational level to account for the shock of COVID-19, we explored the ways in which the work environment in these institutions were reconfigured to accommodate the pandemic. Given that workers in the health institutions were more at risk than those in the educational institutions, we focused first on the educational institutions and then the health institutions.

2.2.1 Teachers’ experiences during COVID-19

As part of the containment measures, schools were closed for nine months. In discussing job demands and job resources then, we considered the different contexts within which teachers carried out their jobs and segmented where necessary, their experiences during the period of the school closures and afterward.

2.2.1.1 Teachers’ job demands during the pandemic

During the nine-month period of school closures, teachers in private schools had to pivot to online tuition for the children, using a combination of Zoom and WhatsApp, a process that required much effort on the part of teachers. When schools reopened in late January 2021, the work pressure increased. For instance,

-

-

There were eighteen children in my class before COVID-19, but we are now thirty. What happened was that most parents like our school because of [the] good environment and infrastructure. Due to that, they sought admission in our school for their children. This increased the number in the class and the workload.

-

Coping with the increased numbers in a time of COVID-19 required rearrangements. Enyonam continued, “Yes, at first, we had five children per table but now we have two per table so there is spacing between them.”

The increased numbers of students also came with an increased responsibility to keep the children safe from COVID-19, a task made more difficult by the fact that children found it difficult to adhere to instructions. Mansah explained her cleanliness routine with her class as follows:

-

-

I always make sure that I sanitize their hands often because, sometimes if I tell them to go and wash their hands, they will not wash it well [properly]. So, I always have the sanitizer on my table, and I call them maybe five minutes, ten minutes’ time I will call them,

“come and sanitize” They are happy too to do it. “Aunty I want sanitizer ”, they are just happy.

-

In Yaa’s class, she described the following routine:

-

-

What we have been doing immediately [since] we resumed from COVID-19 is that every 30 minutes we let them wash their hands and we sanitize their hands and when they come back from break, we sanitize their hands before they get into the classroom and when we close, we will sanitize the tables and chairs before using it the following morning.

-

Enyonam described her stress with the nose mask in her nursery class as follows, “It is very tough, this nose mask thing. We need to talk about it the whole day. I sometimes tell them, “

-

-

Even in the class, when they are playing together, I must pay attention to them always and it is like I am always actively doing something because of COVID-19 making sure things are right. When a child touches something, I make sure he or she washes his or her hands or uses the sanitizer.

-

2.2.1.2 Teachers’ job resources during the pandemic

In discussing job resources, pay was important to our respondents. Although teachers working in private schools continued to teach online during the nine months of school closures, our interviews with some of these teachers indicated that not all of them were rewarded for it. Parents had to be constantly reminded to pay for the online tuition but not all of them did. Private school teachers therefore experienced income losses during that period even though they were teaching online.

A second element of job resources was interpersonal and social relations. This must be considered beyond the confines of the workplace to be able to make sense of the range of job resources available to workers during the pandemic. To enable teachers cope better with the increased job demands of ensuring that children obey COVID-19 safety protocols, the government instituted a new policy that nursery schools would close at noon, but the reality was far from that. As Yaa explained, “Per the government’s policy, schools should close at 12:00 noon, but we are not closing at 12. We close at 3:00 because when we close at 12, parents won’t be at home to pick their children.” The teachers’ social relations with parents had thus made it impossible to adhere to the government directive.

One element of job resources adopted to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the work environment was safety protocols which we defined as the extent to which the work environment had been reconfigured to accommodate COVID-19. While working hours had not been decreased in practice, employers had clearly made efforts to provide this second element of organizational level job resources; PPE, specifically sanitizers were provided, and social distancing rules were being obeyed in the classroom setting.

The reconfiguration of the work environment since COVID-19 was made possible not only by employers, but unions, non-governmental organizations, and the State as well. In the public school where Akos taught, the Ghana National Association of Teachers brought them sanitizers and nose masks.

2.2.2 Health Personnel’s Experiences during COVID-19

Health personnel were considered essential workers and granted mobility exemptions during the three-week lockdown in Ghana. In this section, we explored their experiences at work over the entire period of the pandemic.

2.2.2.1 Job Demands on health personnel during the pandemic

Health service professionals who worked in non-hospital settings found that their work responsibilities had expanded once the pandemic hit. People were afraid to go to hospital for fear of catching COVID-19 there and took instead to showing up in pharmacies and child welfare centres for their health needs. Cynthia, a community health nurse, pointed out:

-

-

Hmmm nowadays patients don’t really go to the hospital anymore because they are afraid …. whenever we go to the child weighing centres, the mothers too will come with their problems instead of going to the hospital. They will start complaining of headaches and other things when they see us in the community.

-

The medical counter assistants we interviewed made similar observations. “The pressure has increased since COVID-19. People no longer go to the hospital because they are afraid getting infected with COVID-19….so, the pharmacy has been busy,” said Nadia. Mortuary attendants’ workload increased dramatically because as part of the measures to contain COVID-19, the government prohibited families from taking their deceased home to dress for burial. Kojo noted that all bodies were to be dressed in a mortuary and the mortuary attendants were to supervise this process while keeping social distancing rules in mind and attending to their other tasks as well. Mary, an orderly, also pointed out that the frequency in which general cleaning took place in hospitals increased from monthly to fortnightly, in essence doubling the workload of hospital orderlies. In Mary’s workplace, the situation had been made worse by the fact that some of the orderlies stopped working for the hospital at the onset of the pandemic, afraid that they would be infected with the disease. Those who did not quit therefore had to take on the additional work responsibilities. They, thus, went from running a 3-shift system to a 2-shift system; the former provided a bit of respite from work on the days when an employee was expected to work a 6-hour shift.24 She noted, “The truth is that the 2-shift system has really doubled our workload.”

The pandemic had not only increased the physical workload of health workers but also added additional psychological stresses associated with the thought of catching COVID-19. Afriyie, a hospital orderly, was anxious prior to getting the vaccine because she had high blood pressure and was worried about the consequences if she caught COVID-19. Cecilia, a nurse, captured her stresses best as follows:

-

-

I start shivering when I see one or two signs. So, I will just go to the laboratory, and they will take my sample; they will take the swap, then I will know the results later. If the result is negative, then I know I am ok, but psychologically, I am traumatised while waiting for the results.

-

A second element of job demands in the time of COVID-19 were the new dimensions that it brought to emotional interactions with clients. Cynthia, a community health nurse, did not interact with clients who refused to wear a nose mask or disobeyed social distancing rules. For those health officials working on the wards, there was an additional dimension to their strained emotional interactions with clients. There simply was not enough resources to ensure that each patient in a public hospital took a COVID-19 test prior to admission. Health personnel were thus working in a stressful environment, unsure of whether they were coming into contact with patients who had COVID-19. Eli, a hospital orderly, explained how this changed their interactions with clients as follows:

-

-

So indeed, there were changes in the environment in the ward. Now we were cautious approaching patients in the ward because we didn’t know who had COVID-19 and who didn’t. If someone coughs in the ward, then there is tension, nobody wants to stay around.

-

Nortey, a medical counter assistant, also noted, “Where I work right now, we still maintain a 6 meters distance rule. Before COVID-19, we came closer to our clients and talked to them because we were not scared of contracting anything from them … but for now the normal interaction with patients has reduced.”

2.2.2.2 Job resources for health personnel during the pandemic

Although job demands had changed dramatically for the worse for all the health service personnel we spoke to, not all of them reported having been adequately motivated at the organizational level with the provision of pay, career opportunities or job security. Among the respondents, the organizational-level job resource of most interest to them was pay. In this regard, given the COVID crisis, it was important to note that the State had announced some incentives such as tax waivers for all health workers and an additional set of incentives for those classified as frontline workers, that is those who worked with COVID-19 patients. Cecilia, a nurse, said, “the government gave us a tax relief for let me say about six or seven months.” Other nurses affirmed this. It was unclear though if orderlies received the benefits or not. Both Afriyie and Eli worked as orderlies in public facilities in the Greater Accra Region. While Afriyie said she did not receive any of these benefits, Eli, noted “The only financial thing that changed in relation to COVID-19 and my salary was the tax waiver. As for that, it reflected in my salary.” It was quite clear though that the benefits extended to health workers only applied to those in the public sector. Kojo, a mortuary attendant, explained as follows, “We are a private facility and so we didn’t receive any of the government’s allowances…. However, our boss was giving weekly allowances to the staff of our facility as well aside their usual salary prior to COVID-19.”

Secondly, given the pandemic, as noted earlier, we expanded Bakker and Demerouti’s organizational level responses to include a category we defined as safety protocols. This allowed us to interrogate the extent to which the work environment was modified to enable workers feel secure and motivated to come into the workspace daily with the full knowledge that their safety was guaranteed. This was a major theme of concern for the health workers in particular, hence the importance of capturing the extent to which workspaces were modified during COVID-19. Three elements were of concern here: reconfiguring the spaces to ensure social distancing; providing PPE; and offering training to be able to work safely.

On reconfiguring workspaces to ensure adherence to COVID-19 safety protocols, Dela, an orderly, explained as follows:

-

-

Before the outbreak, patients and visitors could enter the yard at any time of their choice but since the outbreak, a waiting area has been created. Whenever people are coming into the hospital, they wait, and their details are taken there. After that, they attend to them one after the other. There is also a unique way of sitting [sic] in the waiting area that has been introduced. Two or three people sit on a long bench, which was not the case [before]. These are the changes at my workplace.

-

Similarly, Cecilia, a nurse, explained:

-

-

Because of COVID-19, the place needs to be spacious; they are not supposed to be in crowded environments. So, what we normally do is, when it is time to check the vitals of the patient, one person will sit and wait until that person’s turn before they are allowed to enter. So, the other person will sit far away so that they don’t come into contact with other patients.

-

On the second element of safety protocols, we found that, curiously, while the unions had rallied to provide a safe working environment for teachers in a COVID-19 era, in the hospital setting where the need for PPE was most important, this did not seem to be the general state of affairs. Only Cynthia, a community health nurse, talked about the assistance from her union, “the union provides it [PPE] to [the] region which will be sent to the district, and it will go to the local and come to the hospitals. Last year they supplied every nurse with nose masks.” Generally, unlike the teachers, the health personnel complained about the lack of PPE. Bright, a mortuary worker, lamented as follows:

-

-

We need PPEs badly but at our place, apron and gloves is all we wear to work. It is not good. We have a big exposure here and should there be an outbreak here, we will all be affected. You see mortuary staff in other countries wear PPEs from head to toe. Consequently, their skin is protected as the water they use in cleaning the bodies doesn’t seep through the PPEs. We don’t have it like that here. At times we enter the cold room without wearing any PPEs,

-

And similarly, Afi, a community health nurse, said:

-

-

During the COVID time, when community health nurses were tasked to be visiting clients, educating people on the measures and all that…we weren’t given any PPEs to go. We were also attending to mothers, weighing babies, immunising, and talking to mothers yet still we weren’t given any PPEs except for face masks.

-

Nancy, a medical counter assistant in a private facility, also confirmed that she had not been provided with PPE for work. In the public health facility that Ekoah worked in, not all units had been given a Veronica Bucket for handwashing.25 Frustrated, Nii described the inadequate supplies in the following words, “So, he is trying to tell me that, that one that he gave me, I should use that one through the whole one year and over. How many does he wear? He brought me one, up till now, he has not brought me another. He said I should wear the same one.” Workers were thus having to provide the PPE themselves or go without it. Nancy explained how her parents gave her money to buy N-95s [filtering face mask respirators] for her job as a medical counter assistant. Interestingly, in one private mortuary in Kumasi, the owner provided PPE as well as vitamin C to boost the employees’ immune systems.

It is important to note that of the different categories of health personnel interviewed, Kwame, the environmental officer, was the only one who had no complaint about resources for work. In fact, he seemed to have it in abundance not just for himself but others as well. He said, “All the area councils have PPEs and [as] for the nose masks, we have so many. We sometimes go to the market and distribute it [for] free. If you need pictorial evidence, we can send you some pictures.”

Finally, we explored the third element of safety protocols, that of training for the new reality of COVID-19. Although there was no consensus on the provision of PPE, there was much more consensus on the provision of training for different categories of workers to ensure that they knew how to protect themselves against COVID-19. Aboagye, a mortuary attendant, noted: “yes, we were trained. We were trained at Ho, Battor and numerous places and we still go for these trainings.” Similarly, Ekoah, a nurse, and Eli, a hospital orderly, had also received training, as did Nadia, a medical counter assistant, and Afi, a community health nurse. Only Kwame, the environmental officer, had not received training. He explained:

-

-

Three officers were selected to go to Cape Coast for training on how to handle COVID cases. But in my own small way, I went to the internet and got some information but it's not like they organized a training for us. But some of the officers were trained because they were heading the disposal of the corpses. They are our bosses; we are the junior officers.

-

Job resources were not limited to the organizational level, it included interpersonal and social relations as well. Bright, a mortuary worker, described the ways in which his supervisor had been extremely understanding of his difficulties with transportation during the three-week lockdown. He lived an hour and a half from his place of work and could simply not afford the increased costs of transportation during that period, especially given his low salary. His supervisor therefore agreed that he could simply take his leave during that period.

2.2.3 The Experiences of Traders and Transporters during COVID-19

During the lockdown period, both traders and transporters were allowed to work but with some restrictions; traders had to rotate their presence at work and transporters had to reduce the number of passengers they took on each trip. In this section, we explored their experiences throughout the period of the pandemic.

2.2.3.1 Job Demands on Traders and Transporters during the pandemic

Compared to the employees in the education and health sectors whose job demands, specifically work pressure, had increased quite substantially during this time of COVID-19, cooked-food vendors had a reduced workload, a point noted by both employers and employees alike. For example, Akoto, an employee noted, “I used to close latest by 6:00pm. That was because business was very good, and the rice always finished on time. This is not the case these days.”

Julie, an own account cooked-food vendor, also described her decreased income in the following words:

-

-

I started very small when I first started selling here, but in about two weeks, I was beginning to use three big ice chests and some smaller ones as well. But I had to reduce the quantity of food I prepared when the pandemic started. So now I just cook half of the 3 smaller ice chests you saw when you came around…

-

Oye, an employer, shared a similar sentiment noting that not only had the numbers of people buying food reduced, but that the amount of food people bought had also decreased. Adwoa, yet another employer, also bemoaned the impact of COVID-19 on the food vending business and the incomes of employees/employers in that sector.

Like the cooked-food vendors, street traders of food items also experienced decreases in sales after the lockdown. Adele, an employee, noted “there are days that we sit here all day and make no sales. You know how big this shop is, at times, I cannot even boast of GH¢200 a day [in sales]. That is how bad it has become.” Nonetheless, they had one advantage over the food vendors. Prior to the lockdown, there was quite a bit of panic buying, especially in the capital city, so those who sold non-perishable items made quite a bit of sales prior to the lockdown. This was especially true for those who sold PPE, specifically masks and hand sanitizers as well as non-perishable food items like gari.26 In the first couple of weeks after the pandemic broke, these commodities were in low supply and high demand so traders selling these items hiked up the prices significantly. Indeed, Emmanuel, a self-employed man who worked as a delivery serviceman took to selling sanitizers on the side as a second source of income during the lockdown and admitted, “when we went on lockdown, I made thousands of cedis [hundreds of dollars].”

Another group of employees who lost money during the height of the state-imposed containment measures, specifically the three-week lockdown, were the long-distance drivers who serviced different towns. They had to comply with the government directive to decrease the number of people on the buses thus their earnings were cut short. To make ends meet, they dispensed with their tro-tro mates and, according to Nat, a tro-tro mate, some of them have since refrained from employing tro-tro mates to assist with making change on the long-distance trips.

Other kinds of transport service providers made quite a bit of money during the three-week lockdown. This was especially the case for those working the inner-city routes who were not afraid to risk their lives in the early days of the pandemic. As Kyei, a tro-tro mate, explained:

-

-

Due to the smaller number of passengers, we were asked to pick, we always had passengers by the roadside looking for cars to board and we were able to make a lot because of that. Also, the number of cars reduced, and we were able to work more and make more money.

-

Raymond, a self-employed delivery serviceman, also noted the boom in his business during the lockdown. He said, “Yes, when the government came out to announce the restrictions, work increased because many people were afraid to go out. They ordered their things online.” In fact, in response to the decreased interest in mobility during the lockdown and soon thereafter, there was a boom in the delivery service business. Ultimately though, this worked to the disservice of each one of them, as the pool of customers was finite. Fuseini, an employed delivery serviceman explained, “everybody is doing deliveries these days and it is even difficult for us to get more than 10 customers a day. My work is not much, and the hours have reduced.”

Regardless of whether or not the traders or transporters had decreased work pressure because of the pandemic, like some of the nurses, they were also enduring psychological distress. Linda, a street trader, confided, “When people cough in a car, I will get scared and [will] be asking myself if it is COVID-19.” Joyce, a street trader, described her experience as follows:

-

-

I was very scared …. The day after we recorded the first case, I came to work suffering from a headache, and I was convinced I had COVID because a headache is one of the symptoms…. I also sit in a commercial vehicle and get scared [that] I have contracted the virus from the people in the car.

-

She was not alone in her fear. In fact, as another street trader, Akosua, explained, many of the street traders were deathly afraid. In her words:

-

-

Even if you have malaria, a cold with a blocked nose and the loss of sense of smell, the thinking is you have COVID. And that happened to me a lot. Due to the fear, you are unable to tell others about it when you are experiencing those symptoms because you don’t want them to know. But through my conversations with other market women, I got to know that they also experienced the same symptoms I had but we didn’t talk about it when the whole pandemic started. We were afraid of what might happen to us.

-

As with the changes in work pressure due to COVID-19, there were also changes in the emotional interactions with clients, a point noted by both employers and employees. Oye, the owner of a large food vending business with ten employees noted, “Some of the customers will come here, take a seat, buy water and drinks before ordering for their food but they don’t do that anymore because of COVID-19.” Similarly, Fred, the owner of a street shop, opined:

-

-

The way they interacted with us, all of that changed because some customers come and they have only what they

-

And Joyce, who worked as a street trader, explained:

-

-

The customers who had cars were not even coming out of their cars to the shop but will call me to meet them with the items they want in their cars. Some will not even hand over money to me but would rather throw it to me. Some of them were throwing the money on the floor for me to pick it up.

-

Interestingly, on the third dimension of job demands as outlined by Bakker and Demerouti (2007), the physical environment had improved for some not because the environment had changed, but because they had changed. Lizzy, a food vendor, explained:

-

-

The dust is too much to bear but I must say that wearing of the nose mask has really helped me because I used to get a cold and blocked nose because of the dust in the area. I can say I haven’t had a cold or blocked nose since we started using the nose mask. It has made a difference.

-

2.2.3.2 Job Resources of Traders and Transporters during the pandemic

In terms of organizational level job resources, as with the nursery school teachers and health workers, the respondents focused on two elements: safety protocols and pay. Regarding the safety protocols, employees had received training but not from their employers. Training had come from the efforts of the State or clients. As Akosua, a street trader, explained, “we got public education on both TV and radio. Also, some of our customers were cautioning us to be careful each time they came to the market to buy from us.” Similarly, Linda a street trader said, “nobody officially came to my shop to teach me, but I learnt it from the news on the television and radio.” John, the owner of a delivery service business, was getting his education from his daughter, who in turn was getting it from school.

While some of the employees/employers took the pandemic very seriously and used PPE, others did not. Raymond, an own account delivery serviceman, likened the pandemic to a war and thus went out daily prepared to face it. In his words, “so as far as I am a soldier, I need to know that war can come at any time. I am prepared for it. So, when I am going to work, I wear my mask, I wear my gloves; I cover everything. I even wear glass [a face shield] you know.”

Selorm, a tro-tro mate, was also quite firm in his usage of PPE and insisted that clients use it as well. He explained, “The driver and I use the nose mask, and before we set off all the passengers also have to wear their nose masks or else, we tell the passenger to alight from the bus.” Kyei, another tro-tro mate, was adhering to the handwashing protocols. He noted, “After collecting the money then I will sanitize my hands intermittently.” On the other hand, Mabel, the owner of a food vending business, was not wearing her mask at work because in her words, “I am uncomfortable wearing the nose mask because I am asthmatic.” Nonetheless, she was insisting that her employees wore it.

It was not always easy to adhere to the safety protocols. Sometimes, it interfered with customer service. Julie, an own account food vendor’s experiences in this regard were instructive. She said:

-

-

Right now, I have the sanitizer. After I serve about one or two customers, I will use it, but I forget about the sanitizer when there are many customers buying at a time, and I use it only when I am done serving all of them. If I don’t do that, some of them will complain. They will say “Madam, I am in a hurry; madam I am this” so I just attend to them and sanitize my hands when I am done.

-

Others focused on adhering to social distancing rules. Lizzy, who owned a food vending enterprise, explained:

-

-

I used ropes to serve as a barricade to ensure social distancing and my customers were expected to stand behind the rope when they came to buy from me. I also ensured that those who sat down and ate their porridge at my workplace didn’t sit close to each other.

-

Some shop owners such as Fred bore the cost of PPE for employees. In his words, “I also had to provide sanitizers, nose masks, and a whole lot. We also provided face shields to all our employees at the beginning of the pandemic. I remember it was very expensive, but we had to procure them for the employees.” Others relied on the benevolence of outsiders. For example, some of the tro-tro mates and food vendors like Mabel, who worked in bus stations, benefitted from the largesse of the Ghana Private Road Transport Union which provided Veronica Buckets in some stations. In other stations, politicians had shown up with the PPE. Patrick, a tro-tro mate, named both the sitting MP and a former MP in his constituency who provided PPE. However, some employees had provided the PPE themselves because employers failed to provide it. Such was the experience of Akoto who worked as a food vendor. He recalled, “I bought the Veronica Bucket, nose mask and hand sanitizer myself. The owner of the business didn’t provide anything for us. We bought everything from our salary.”

In terms of pay, there had been three responses to the pandemic. One group of employers passed on the decreased business sales to the employees by cutting their incomes. One such employer was Oye, the owner of a food vending business, who acknowledged that she decreased the incomes of her ten employees for two months after the lockdown because of poor sales and only increased it when business started to pick up. Other employers personally bore the costs of decreased business sales but paid the employees as expected. Such was the case with Adele, the owner of a street shop, who paid her one employee but as she put it, “the money is not coming into my pocket as I prefer.” In other words, her profit margin had decreased. In the third case, employers sought to motivate the employees during the COVID-19 period by paying them an additional sum of money. Thus, Fred who owns a street shop, said:

-

-

Oh yes, everyone got their bonuses.

. We did this during COVID because the work we were all doing here became risky and deadly. So, we decided to motivate them a little so that they can continue coming to work. We did this for about two months.

-

Finally, among our 50 respondents, only tro-tro mates noted the changes in interpersonal and social relations to accommodate the realities of COVID-19. Dan and Kyei noted that the owners of the cars they drove demonstrated recognition of the difficult circumstances. As such, the sum of money they were expected to pay daily, known in Ghanaian parlance as daily sales, was decreased.

2.3 Workers’ hopes and aspirations for the future

Several themes were evident in the workers’ hopes and aspirations for the future. While some of the sentiments they expressed bore a semblance to the stresses brought on by COVID-19, the majority did not, a point to which we shall later return. In this section, we discuss these aspirations by focusing first on those centred on COVID-19 and then the more general sentiments.

2.3.1 Aspirations linked to COVID-19

A major theme directly linked to the experience with COVID-19 was continued public education in a COVID-19 era. Fred, the shop owner, noted:

-

-

The government should continue and let us know that these measures helped us a lot so we should continue to observe the safety protocols. The awareness and education should continue. The virus is still with us, and we need to protect ourselves. The talks and discussions about it seem to have reduced and some people think we are back to our normal times but that is not the case.

-