Growth, economic structure and informality

Abstract

This paper explores the relationship between economic growth and informality and highlights the role of GDP growth and its composition in the level and evolution of informality, using country data from 1991 to 2019. The analysis reveals a weak relationship, although with important differences across regions and income levels. Coefficients are higher in middle-income countries. This means that the same growth rate generates different impacts on informality depending on the country, probably due to pre-existing levels of informality, the economic structure or institutional and other variables. Economic structure appears to be the key determinant of informality, even after controlling for endogeneity, using different proxies of informality or including institutional variables. These results confirm that the economic structure and pattern of growth matters for formalization. This calls for policies that promote changes in the productive structure, including a broader, more diversified base and more economic complexity and technological sophistication, to ensure inclusive growth.

Introduction

A half century after the coining of the concept of informality – first used in the early 1970s, the term remains debated regarding its definition, its measurement and which policy approaches will make the transition to formality. That said, several agreements have reached consensus at the international level.1 The easiest and greatest agreement is on the fact that informality is a widespread phenomenon, which is increasingly evident thanks to the expanding availability of data.2

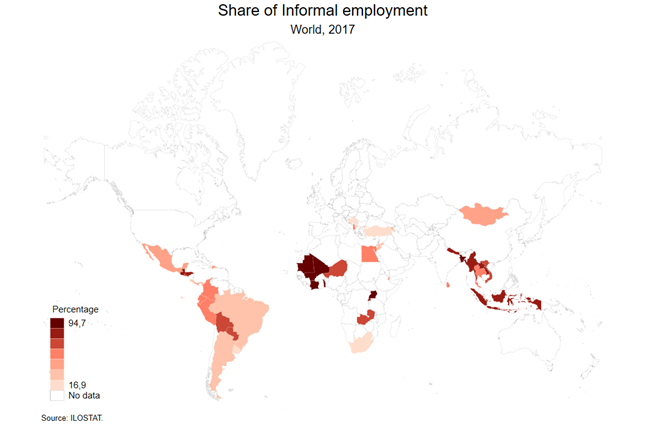

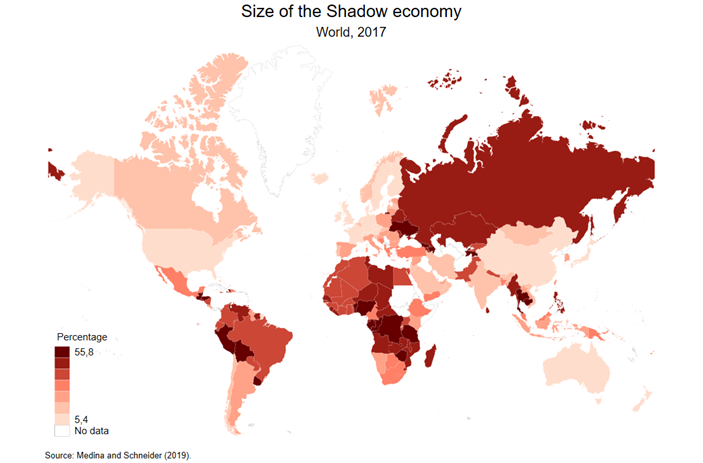

Recent data confirms that informality is a phenomenon of great magnitude. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) (2018a), some 60 per cent of global employment is informal (of which, 85 per cent is in the informal sector). For many years, informality in the labour market – informal employment – had been the sole indicator of informality available on a global and regional basis. However, informality has multiple dimensions, including in product markets. This has become clear more recently as we have learned that informal gross domestic product (GDP) fluctuates between 15 per cent and 35 per cent of total GDP, depending on the region (Ohnsorge and Yu 2021; Deléchat and Medina 2021).3 These two figures also highlight the large productivity differences between the formal and informal economies.

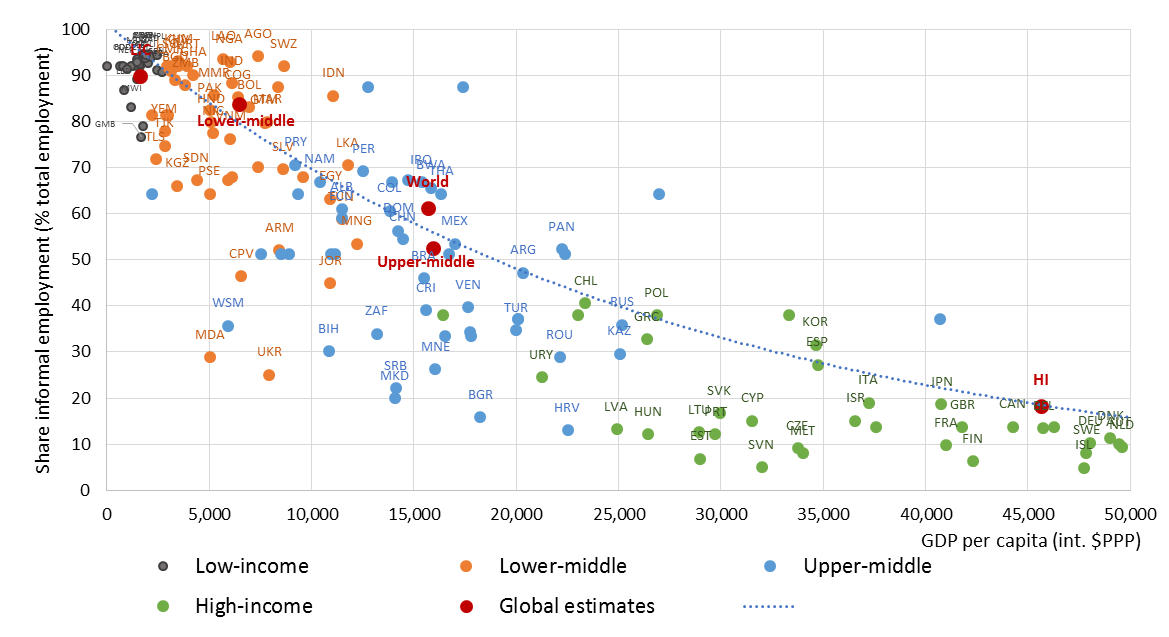

The increasing availability of global or cross-country data allow us to revisit one of the earliest topics on informality: its relationship with economic growth. Figure 1 shows an overall negative relationship between the share of informal employment and GDP per capita, which means that those countries with a high GDP per capita tend to have low informality rates. However, for the same level of GDP, there is large heterogeneity or dispersion: in lower-middle-income countries (GDP per capita between $5,000 and $15,000 purchasing power parity), informality rates range from 20 per cent to more than 90 per cent; and in upper-middle-income countries (GDP per capita between $10,000 and $25,000 purchasing power parity), informality rates range from 15 per cent to more than 80 per cent.

That this relationship has a large dispersion means that GDP per capita is only a necessary condition for formalization, not a sufficient one. In other words, there are other variables affecting this relationship. A major strand of the literature highlights the role of institutions. A less empirically explored angle is the role of economic structure: Not all countries reach the same level of GDP per capita with the same composition of industry sectors. In fact, countries with the same level of GDP per capita may have very different economic structures or patterns of growth.

Figure 1. Global share of informal employment and level of GDP per capita, by country income level, 2016

Source: ILO 2018a.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, to explore the relationship between economic growth and informality.4 Second, to analyse the role of the economic structure (or composition of GDP) on the level and evolution of informality using the most recent data on informality.

Related literature

The relationship between informality and economic growth is one of the oldest debates related to labour markets, especially in developing countries. Many studies have linked the roots of informality with the dualist approach (Lewis 1954). In a dualist society, there exists a “capitalist” sector (intensive in capital) and a “subsistence” sector (intensive in unskilled labour), typically agriculture. In this scenario, the expansion of the capitalist sector is possible by a shift of unskilled workers from subsistence to the capitalist sector. Another two-sector view is the rural–urban migration model of Harris and Todaro (1970), which explains why the number of rural-to-urban migrants could exceed the number of available urban jobs, resulting in open urban unemployment.5

In all these models, a critical element is the type of relationship between the formal and informal economies. Tokman (1978) identified three types of interrelationships. He mentioned a “benign” relation (autonomy or integration) on one hand and, on the other, a relation based on the “subordination” of the informal sector to the formal sector. And he suggested a third type based on the existence of elements of “heterogeneous subordination”: While the informal sector exists with some autonomy, it also has important linkages with the rest of the economy, depending among other things, on the type of specific economic sector or product market characteristics. More recently, Weller (2022) emphasized the individual characteristics of people who move from the informal to the formal economy and the specific phase of the business cycle (growth, low growth, crisis) as determinants of this relationship.

Unfortunately, due to the lack of large time-series data on informality, there is little empirical evidence on its relationship with economic activity. Loayza and Rigolini (2006), using self-employment as a proxy of informality and data for 93 countries, found that in the long run, this variable is larger in countries with a small GDP per capita. Although in the short run, informality is found to be countercyclical in a majority of countries. In particular, Loayza and Rigolini found an elasticity (informal employment to GDP) of -0.07 and of -0.05, when other variables are included. This elasticity seems to be more negative (larger in absolute value) as GDP increases.

Kucera and Xenogiani (2009) correlated GDP and the share of non-agricultural informal employment and concluded that, “at least in the medium term, economic growth does not necessarily lead to a fall in informal employment”. Jutting and de la Iglesia (2009) presented data by region over three decades, from 1975 to 2007, for selected countries in Latin America and South and East Asia and concluded that, over this period, growth was accompanied by increasing – not falling – non-agricultural informal employment.

La Porta and Schleifer (2014) used a panel of 68 countries with data from 1990 to 2012 and found a negative correlation between GDP per capita and self-employment. They concluded that “doubling GDP per capita is associated with a reduction in self-employment of 4.95 points”. At a regional level, Macroconsult (2014) found that in Latin America from 1990 to 2012, the employment-to-GDP elasticity was 0.36, but the formal employment-to-GDP elasticity was 0.17. Thus, the capacity to create formal employment in the region over that period was almost half of the employment generation capacity overall.

More recently and using its own estimates of informal output as well as ILO self-employment data for 179 countries from 1990 to 2018, the World Bank (Ohnsorge and Yu 2021) found that while informal output moves in the same direction as formal output, self-employment does not co-move with the formal economy. Even more, while formal employment is positively and significantly correlated with formal output, informal employment (self-employment) is largely uncorrelated with formal output in emerging and developing economies (Ohnsorge and Yu 2021). Using data from 158 countries for 1996 to 2015, along with estimates of the shadow economy, Wu and Schneider (2019) suggested that the relationship between the shadow economy and GDP is non-linear. They proposed instead a U-shaped relationship.6 The implication of this non-linearity is that the shadow economy is able to coexist with different levels of development and does not disappear in the long term (Deléchat and Medina 2021).

Other variables affecting this relationship

The fact that informality persists despite economic growth has generated different theories, emphasizing the influential role of other variables in this relationship (between informality and economic growth). Some theories highlight the influence of institutional factors. Originally developed by De Soto, Ghersi and Ghibellini (1986), this approach points out that informal economic units (and as result, business owners and workers within those units) are forced to be informal due to the lack of capital, inadequate demand and high costs in money and time of the long and cumbersome procedures involved in setting up a formal enterprise to operate with limited resources and at very low levels of productivity and income. According to this view, informal workers or economic units usually do not have a legal title for their land, property or productive assets. And for this reason, they have limited access to the financial system, and therefore the removal of some legal obstacles is essential for the potential of the informal economy to be released.

A variant of this approach is one that considers informality results from a voluntary decision by a worker or economic unit, characterized as “exiting”: The worker decides to operate outside of the legal rules after comparing benefits and costs of formality in such areas as registration, taxation, wages and social security, among other things (Levi 2008; Perry et al. 2007; Maloney 1999; Fields 1990).

Another approach, also centred on institutions, focuses on the weakness of public administration, with particular emphasis on inspection and enforcement systems. In this perspective, Kanbur (2009) highlighted the need for a theory of “law enforcement” – a subject of great importance in countries where laws are often adopted but not enforced.

Empirically, Loayza (2008) analysed the institutional determinants of informality with data until 2007, taking into account that informality is a complex phenomenon due to the combination of various forces. The dependent variables were the share of non-affiliated workers to the pension system and the share of self-employment. The covariates are the component of rule of law of the International Country Risk Guide and the Economic Freedom Index of the Fraser Institute. He also controlled for education, sociodemographic variables and the share of agriculture in GDP. His results indicated that the relative importance of each factor was differentiated by countries; “for example, in the case of Peru, institutional factors may be more relevant when comparing its level of informality with Chile, but if it is compared to the United States, the structural factors (and especially educational level) are most important.”7

Using data from World Bank surveys, La Porta and Schleifer (2014) indicated that the greatest perceived obstacle to doing business among both formal and informal firms is lack of finance, political instability or access to land. They concluded that it is difficult to read this evidence as pointing to the institutional environment as the central obstacle. Instead, they proposed and tested the role of variables, such as entrepreneurial and management skills, concluding that the main restriction is not the supply of educated workers but the supply of educated entrepreneurs – or people who can run productive business.

Other authors have highlighted the role of the economic structure. Pinto (1970) proposed that the majority of countries have an economic structure whereby different economic units coexist with large differences in the use of technology, which is the main characteristic of the economic structure that in turn generates a differentiation in the labour market in terms of income and working conditions. Productive structures become unequal in part due to the uneven penetration of technology.8 Infante and Sunkel (2012) argued that when this happens, the economic structure is divided into several productive sectors. Sometimes, the high productivity sector is called “modern” and low productivity characterizes the “traditional” sector, in clear reference to the use of modern or traditional technologies. These authors argued that productivity differentials were observed when comparing economic sectors, but more importantly by firm size. The latter was particularly important for developing economies because it allowed for inclusion within the analysis of the coexistence of firms from very heterogeneous productivity within each sector.

The “economic sector” approach attributed a primary role to the manufacturing sector in the economic dynamics and growth processes because it traditionally had been the nucleus of the creation of capacities, knowledge and learning processes that occur together with investment and production.9 While there is discussion on whether this sector has stopped having the relative importance it had in the past, in developing countries, the role of large firms is particular because they have a large and probably increasing influence on multiple sectors due to their increasing horizontal (sectoral) and vertical integration (firm size). The traditional firm that specialized only by sector and vertically integrated from the stages of raw materials to the final products has evolved into a configuration in which activities of these large firms also expand horizontally to other sectors, including production of goods and services (financial, commercialization, communication, information, transport, tourism, etc.). However, within each sector there are large firms that are the leaders of the process of modernization and technological improvements. But also, there are small firms with low productivity where the majority of employment concentrates. Firms with highly different productivity levels within a sector do not necessarily compete in the same product market segments because there are also differentials in the demand for final goods, and usually this differentiation is seen in the quality dimension of the goods produced.

Comprehensive perspectives

An increasing number of studies and policy documents more recently have highlighted the role of multiple variables that influence informality, which thus requires for a comprehensive approach to formalization. Loayza (2018a, 2018b) emphasized that informality does not have one unique determinant but is the result of a combination of drivers, including low productivity, institutional quality (including the capacity to enforce regulations), difficulties doing business and economic structure (the importance of the rural sector, for example).

The multidimensionality of informality is a direct implication of the fact that there are different although interrelated types of informalities. There is formal and informal production, formal and informal economic units and formal and informal workers. There has been an analytical tendency to focus on the latter. Recent research emphasized, for example, that business and labour informality have similar determinants but also specific ones and thus suggested a sequence in the process of formalization: with the formalization of informal enterprises being a requisite for the formalization of workers employed in the informal sector (Diaz et al. 2018).

Added to that point of view, there are different subgroups within what is usually called “informal” due to the high heterogeneity discussed in literature for decades.10 Ulyssea (2018) distinguished three types of informal sector units that correspond to different views of informality. The first view (the legalistic view) argues that the informal sector is a reservoir of potentially productive entrepreneurs who are kept out of formality by high regulatory costs, most notably entry regulation. The second (the parasite view) sees informal firms as “parasite firms” that are productive enough to survive in the formal sector but choose to remain informal to earn greater profit from the cost advantages of not complying with taxes and regulations. The third (the survival view) argues that informality is a survival strategy for low-skilled individuals who are too unproductive to ever become formal.

More generally, Kanbur (2021) argued that faced with government intervention or regulation, economic actors can be classified in four categories: (i) those covered by regulation and in compliance; (ii) those covered by regulation and not in compliance; (iii) those covered by regulation initially but then adjust their behaviour in a way that puts them out of coverage; and (iv) those not covered by regulation. Informality is not uniform, and each type of informality has its own specific causes.11

The policy discussion has also evolved in this perspective. ILO Recommendation No. 204 concerning the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy (2015) advocates for an integrated and comprehensive approach to formalization. This entails recognition that not all informal workers and economic units are informal for the same reason and that the causes of informality are many and operate in multiple dimensions. Thus, formalization policies need to take a multidimensional approach involving multiple initiatives and actors, including an important level of coordination and monitoring. Single or isolated initiatives or policies (the silver bullet approach) will hardly succeed in the transition to formality.

These recommendations are consistent with lessons from real formalization episodes. Salazar and Chacaltana (2018) analysed 11 episodes of formalization to explain the 5 percentage points of reduction in informality in Latin American countries between 2005 and 2015. They found that these countries used four main pathways to formalization: productivity, regulations, incentives and enforcement. They highlighted the role of the context of high and sustained economic growth as an important enabler of the process. Infante (2018), analysing the same region from 2012 to 2015, found that economic variables explained 60 per cent of the reduction and institutional variables explained the remaining 40 per cent. Of course, these proportions are probably different in other regions because the ultimate determinants of informality (or formality) in a specific country or region must be established empirically, and not theoretically, and according to the circumstances in each case.

Evidence from recent meta-analysis also points in the same direction. After their systematic review of studies, Jessen and Kluve (2021) found that despite the great discussion on policies for the transition to formality, there are few studies that empirically evaluate the impact of interventions to reduce informality. And the majority of those few studies are in Latin America. They also found that the effect of the interventions tends to be better in a favourable labour market context; that tax incentives and information – in combination with other instruments – tend to have a positive impact; that initiatives on labour formalization tend to be more effective than the ones that aim to formalize firms; that larger programmes are more effective than limited interventions; and that the long-term effect may be more positive than the impact in the short term.

Floridi, Demena and Wagner (2020) also found few impact studies on business formalization. What they did discover indicates that these types of interventions have positive and significant effects but they also tend to be small in magnitude and that long-term effects tend to be more positive than the immediate impact. Importantly, effects are more likely to be positive in small and medium-sized enterprises than in microenterprises.

Despite all the discussion on informality, that there are few impact studies underlines the need to further expand the evidence base for policy recommendations. However, even the scarce evidence demonstrates that, because most individual interventions exhibit small impacts that tend to disappear in time, an integrated approach based on multiple, coordinated and sustained in-time interventions is needed, just as Recommendation No. 204 suggests.

Informal economy – An update

The original discussion on informality was essentially multidimensional and linked to the world of work and the world of production.12 In time, however, more emphasis was directed to measuring informality in the world of work.

The first international statistical standard on informality was on the “informal sector” – an enterprise-based concept that, by extension, allowed the measurement of “employment in the informal sector” via households or labour force surveys. That concept then evolved into “informal employment”, which includes informal employment in the informal sector, in the formal sector and in households (ILO 2021a; ILO 2003).13 More and more countries now include questions in their national surveys to assess informal employment, and many apply the recommended criteria for their national estimates. To arrive at harmonized comparable estimates of informal employment, the ILO in recent years systematically applied recommended criteria based on the characteristics of economic units for independent workers and on access to labour and contributory social protection for employees (see box 2 in ILO 2018a). Those criteria directly link to the notion of coverage and compliance by formal arrangements with obvious policy implications when interpreting the situation of different groups of workers but still focusing on the employment and, to some extent, the enterprise dimensions.

Progressively, the policy discussion on informality is evolving towards the “informal economy”, as suggested by ILO Recommendation No. 204. The emphasis on the “economy” highlights the fact that there are not only workers and enterprises but also activities, production processes and transactions that can be formal or informal. Several estimations of informal production have been made available. Table 1 shows some of them. The simple average of their estimations situates informal production in the world at around 27–29 per cent of total GDP. Note that this indicator would be lower if we used a weighted average rather than a simple average because economies with large GDP have a small share of informal production.

In any case, the ILO (forthcoming) has estimated that 60 per cent of global employment was informal in 2019.14 Due to the considerable methodological differences with both figures, if we used a global informal production share in the range of 27–29 per cent and a share of informal employment of 60.5 per cent, then these figures imply a formal to informal productivity differential of more than four times the global level, which rises to more than 16 times in developing countries.

Table 1. Informal output and informal employment, by country income level

|

Advanced economies |

Emerging economies |

Low-income developing economies |

World |

|

|

Informal production estimates |

||||

|

World Bank (Ohnsorge and Yu 2021) 2010–2018 a/ |

17.6 |

32.8 |

29.2* |

|

|

IMF (Deléchat and Medina 2021) 2010–2015 b/ |

15.0 |

27.6 |

38.8 |

n.a. |

|

Medina and Schneider (2019) 2010–2017 b/ |

14.2 |

27.9 |

36.3 |

27.4* |

|

Informal employment estimates |

||||

|

ILO 2018a (circa 2016) |

20.9 |

67.3 |

89.1 |

60.5** |

Note: *=simple average; **=weighted average. a/= dynamic general equilibrium model; b/= multiple indicators, multiple causes model.

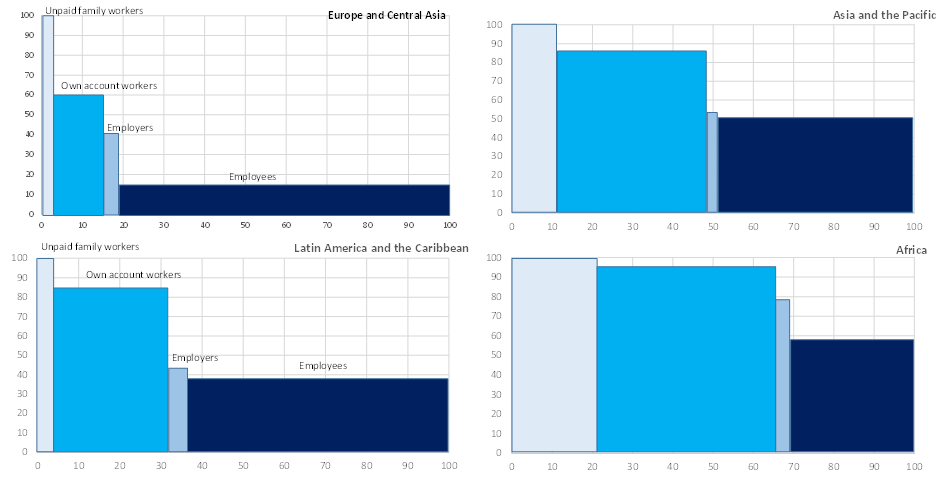

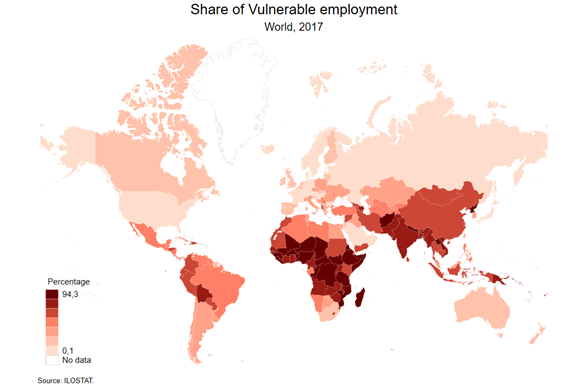

As discussed in the literature review section, productivity differentials have been linked to the existence of different labour market conditions, including informality, for workers. Figure 2 highlights this fact, using a simple economic status disaggregation, although it can also be done using a sectoral or firm size disaggregation.15 For unpaid family workers, for example, informality is by definition 100 per cent. The difference between regions of the world is the share of workers in this category, being the lowest in Europe and Central Asia and in Latin America and the largest in Africa. Informality rates for employers are similar across regions, as is their share in total employment.

The most important divide, however, is among persons working as employees (salaried work) and persons working as own-account workers. Figure 2 shows that employees have small shares of informality in all regions of the world, while own-account workers have shares greater than 60 per cent even in Europe and Central Asia. Again, the difference between regions is the proportion of employment in each category. Of course, there is room for policy to try to facilitate the transition of every specific subgroup (working in the vertical axis). But figure 2 makes it very clear that another pathway to formality is to work on the horizontal axis, such as the relative proportions of each category of workers in total employment. That is notably related to the structure of the economy and the labour market.

Figure 2. Informal employment, by economic status and region, 2019

Note: Y axis= informality rate. X axis= cumulative share of employment.

Source: ILO forthcoming.

Similar conclusions were reached when we looked at the data by size of economic units, which indicates a negative correlation with informality (table A1 in the annex). In all the regions analysed and for the world, informality rates for economic units of one worker are the same as those provided here for own-account workers. The proportion of informal employment is still large in economic units, with two to nine workers (78.7 per cent), and is slightly more than 40 per cent in economic units with 10–49 workers. For firms with more than 50 workers, informality rates are less than 30 per cent on average. Again, what really differentiates the income groups of countries is the structure of the labour market by size of economic units. Establishments with fewer than ten workers account for about 57 per cent of total employment globally, but this figure increases to more than 80 per cent in lower-middle- and low-income countries (at 82.9 per cent and 86.5 per cent, respectively). Moreover, the proportion of employment in enterprises with more than 50 workers, which globally stands at 28.7 per cent, falls to 12.9 per cent in lower-middle-income countries and to 8.2 per cent in low-income countries. By contrast, the proportion of employment in firms with more than 50 workers accounts for 46 per cent of total employment in high-income countries.

Therefore, the first policy implication here is that the labour market composition – in terms of employment status as employees or own-account workers, for example; or economic sector of high or low productivity, for example; or enterprise size – is a determinant of the overall informality rate in a country or region. This is consistent with the structuralist view of the labour market and supports the idea that it would be difficult to reduce informality levels in a sustained way without changing production and labour market structures, which mainly relate to the level and patterns of development.

Methodology

To analyse the relationship between economic growth and informality, our methodological approach was to run a series of cross-country regressions. We focused on the relationship using variations – rather than levels – of these two variables because we are interested in explaining what determines formalization or informalization processes.

To assess the role of the economic structure on informality, we followed the methodological strategy used by Ravallion and Chen (2007) and Loayza and Raddatz (2010), who linked the composition of growth to the evolution of poverty.16 Essentially, we used an equation linking changes in informality to the changes in the sectoral composition of growth across countries. For this, note that GDP can be decomposed as:

Where = GDP per capita in time t, GDP per capita in sector s in time t and is the proportion of GDP in sector s in time t in total GDP. This decomposition also holds for the standardized variable GDP per worker, calculated by dividing global GDP and sectoral GDP by the total number of workers in each country. Using this decomposition, then the variations in the informality rate can be estimated as

As several authors have noted,17 if all coefficients are equal () in this specification, then this equation becomes an ordinary aggregate regression between the change in the informality rate and changes in GDP. Thus, the hypothesis to test here would be (H0: ), if all coefficients are equal. If that hypothesis cannot be rejected, then only aggregate growth matters and not its composition. On the contrary, if H0 is rejected, the composition of growth matters for the reduction of informality.

Data

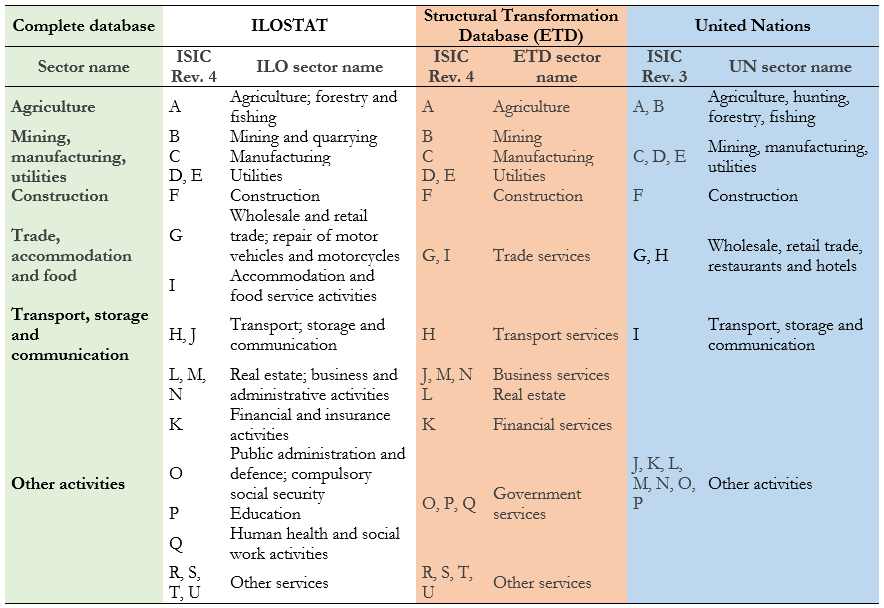

For the sectoral decomposition of GDP, we used two data source alternatives. First, the information on sectoral composition of GDP comes from the United Nations Statistics Division’s National Accounts data (UNdata) in seven economic sectors.18 This data set includes time series for a broad number of countries and time (since 1970). Then, to confirm our results, we used a ten-sector disaggregation from the Economic Transformation Database constructed by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research and the Groningen Growth and Development Centre of the University of Groningen (the Netherlands). The GDP data are at constant 2015 prices in local currency.

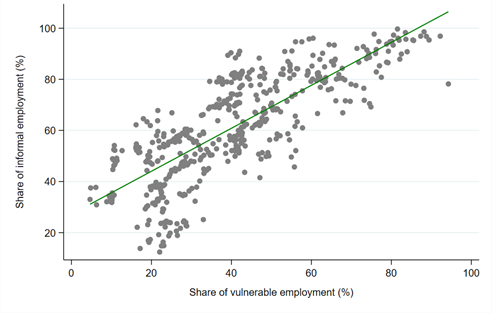

In the case of informality, we tested two variables. The first one is the share of informal employment in total employment following the ILO harmonized definition.19 This data set has time series for 94 countries of different sizes from 1997 to 2020. The second indicator, which is not about informality but is highly correlated, is the vulnerable employment, which is the sum of own-account workers20 and contributing family workers. This data set, from ILOSTAT, contains time series for 189 countries from 1991 to 2020. Both series show an important correlation, as depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3. Correlation between informal employment and vulnerable employment, 1997–2019

Source: ILOSTAT.

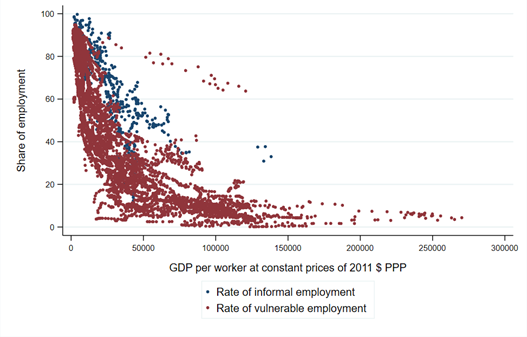

The information on informal employment, however, is small and particularly concentrated in some regions of the world. Figure 4 shows this clearly. The dots in blue correspond to the observations available for informal employment, and the red dots correspond to the information available for vulnerable employment. It is clear that the series of informal employment do not cover the high-income countries and is more concentrated in middle-income countries. Latin American and Caribbean countries, in particular, represent 36.4 per cent of the total number of countries in both series for 2019.

Figure 4. Informal employment and vulnerable employment compared with GDP per worker, 1997–2019

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

Results

We present the most important results of our analysis for the two indicators available, informal employment and vulnerable employment.21

Informal employment

The informal employment and sectoral GDP series includes 43 countries and nearly an average of eight observations per country for the period 2000–2019, which provides 331 observations in variations. The main results are shown in table 2.

We tested several econometric specifications for the estimation of the overall relationship in percentual changes between GDP and informality and for the relationship between the composition of GDP and informality: pooled data regression using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), the random effects model and the fixed effects model. In each case, we present the overall coefficient (B) for GDP and also the sectoral coefficients (Bs) for the sectoral composition of GDP. The Hausman test indicates that the preferred model is the fixed effects model, with a probability of error at less than 10 per cent. For this reason, we used this model for the remainder of the analysis.

The coefficient of overall economic growth on informality indicates that the effect of an increase of 1 per cent in GDP per capita is associated with a reduction of the share of informal employment in total employment, at around -0.32 to -0.38 per cent. The latter was observed in the fixed effects model.

We then ran the same regression for the composition of GDP to test the hypothesis that all coefficients are equal. In this case, this hypothesis was rejected with the panel data models. The tests of equality of coefficients indicated that with the pooled data model, the hypothesis that all coefficients are equal could not be rejected, at 90 per cent confidence. However, with the random effects model and with the fixed effects model, this hypothesis was rejected with more than 90 per cent confidence.22

Table 2. Regression: Share of informal employment in total employment and composition of growth using annual growth rates, 2000–2019

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pooled |

Pooled |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

|

|

Variables |

Linear regression (OLS) – overall |

Linear regression (OLS) – sectoral |

Random effects – overall |

Random effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.319*** |

-0.337*** |

-0.378*** |

|||

|

(0.066) |

(0.062) |

(0.069) |

||||

|

Agriculture |

0.235 |

0.112 |

-0.035 |

|||

|

(0.398) |

(0.316) |

(0.346) |

||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.738*** |

-0.711*** |

-0.736*** |

|||

|

(0.249) |

(0.241) |

(0.261) |

||||

|

Construction |

-0.334 |

-0.457* |

-0.605** |

|||

|

(0.219) |

(0.239) |

(0.253) |

||||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

0.191 |

0.379 |

0.633* |

|||

|

(0.399) |

(0.314) |

(0.331) |

||||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.489 |

-0.677 |

-1.036 |

|||

|

(0.682) |

(0.601) |

(0.669) |

||||

|

Other activities |

-0.455* |

-0.529** |

-0.636*** |

|||

|

(0.244) |

(0.210) |

(0.243) |

||||

|

Constant |

-0.004** |

-0.004* |

-0.003 |

-0.003 |

-0.003 |

-0.002 |

|

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.002) |

(0.003) |

|

|

Observations |

331 |

331 |

331 |

331 |

331 |

331 |

|

Number of countries |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

|

R-squared |

0.077 |

0.095 |

0.094 |

0.131 |

||

|

RMSE |

0.0374 |

0.0373 |

0.0358 |

0.0356 |

0.0360 |

0.0356 |

|

F/Chi 2-test |

23.13 |

5.163 |

29.37 |

38.15 |

29.77 |

7.087 |

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 |

2.31e-06 |

4.36e-05 |

5.98e-08 |

1.05e-06 |

1.05e-07 |

4.80e-07 |

|

F/Chi 2-test – equal coefficients, all |

1.509 |

8.114 |

2.849 |

|||

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 – equal coefficients, all |

0.199 |

0.0875 |

0.0243 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

These results indicate that differences exist in the effect of growth in different sectors on informality. This also implies that not only overall economic growth but a particular type or pattern of growth is what matters. In particular, there are some sectors with large negative coefficients, such as mining, manufacturing and utilities, construction and other activities, that could be seen as modern sectors, in contrast to traditional sectors, such as agriculture.23 However, this does not mean that other sectors are not relevant for a comprehensive strategy on informality because they could be supporting the transition to formality in a broader sense. The idea of “transition to formality” refers to a gradual process, including policies to support the “formalization” of workers and enterprises that have the greater potential to formalize and also policies to address decent work deficits of workers and economic units in the informal economy.24

The data set is small and does not allow detailed disaggregation. Yet, tables A3 and A4 in the annex decompose the results by income level and geographical regions. Due to the small number of observations, the focus is on a decomposition between low-income and lower-middle-income versus upper-middle-income and high-income countries. In the first two columns of table A3, we reproduce the results of the fixed effects model in the previous table. In the case of low- and lower-middle-income countries, we observed that the effect of overall economic growth is largely lower (at -0.06) and turns statistically non-significant. And in the case of upper-middle-income and high-income countries, the coefficient remains significant and is larger (at -0.48) than the coefficient found for the complete sample (at -0.37). The non-significant effect of overall growth in lower-income groups of countries could also be influenced by the small number of countries in this sample.

When we analysed the results by ten economic sectors (table A5 in the annex), we found that the sectors where economic growth results in the largest declines in informality in lower-income countries are mining, manufacturing and utilities. In the case of high-income countries, the sectors that have more negative coefficients on informality are construction and other activities.

Vulnerable employment

To verify our results with a larger data set, we then used the second indicator as a proxy of informality: the share of vulnerable workers in total employment.25 In this case, the matched data set includes information for 182 countries from 1991 to 2019, which provides information for nearly 4,800 observations (in variations).

When this indicator was used in the six-sectors specification, the results from the previous regression were confirmed (table 3). The Breusch–Pagan test indicates that it is preferable to use a model of panel data rather than a model of pooled data. However, in this case, the Hausman test indicates that there is no difference between a model of random effects and a model of fixed effects.26

In any event, the results are similar in the three models. The overall effect of GDP growth on the reduction in the share of vulnerable employment is confirmed, although the magnitude of this effect is notably lower (at -15.7 per cent) than in the previous analysis because this data set contains information for the majority of low-income countries. In general, a reduction of 1 per cent in the rate of vulnerable employment requires 6 per cent in overall economic growth.

Table 3. Regression: Share of vulnerable employment and composition of growth using annual growth rates, 1991–2019

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|

Pooled |

Pooled |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

|

|

VARIABLES |

Linear regression (OLS) – overall |

Linear regression (OLS) – sectoral |

Random effects –overall |

Random effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.140*** |

-0.150*** |

-0.157*** |

|||

|

(0.009) |

(0.010) |

(0.013) |

||||

|

Agriculture |

-0.074*** |

-0.079*** |

-0.082*** |

|||

|

(0.021) |

(0.024) |

(0.021) |

||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.144*** |

-0.153*** |

-0.157*** |

|||

|

(0.017) |

(0.018) |

(0.015) |

||||

|

Construction |

-0.259*** |

-0.263*** |

-0.265*** |

|||

|

(0.038) |

(0.039) |

(0.041) |

||||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.122*** |

-0.143*** |

-0.155*** |

|||

|

(0.033) |

(0.034) |

(0.041) |

||||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.280*** |

-0.279*** |

-0.280*** |

|||

|

(0.058) |

(0.066) |

(0.064) |

||||

|

Other activities |

-0.112*** |

-0.123*** |

-0.129*** |

|||

|

(0.024) |

(0.025) |

(0.027) |

||||

|

Constant |

-0.004*** |

-0.004*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.004*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.003*** |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Observations |

4 796 |

4 792 |

4 796 |

4 792 |

4 796 |

4 792 |

|

Number of countries |

182 |

182 |

182 |

182 |

182 |

182 |

|

R-squared |

0.044 |

0.052 |

0.,052 |

0.060 |

||

|

RMSE |

0.0285 |

0.0284 |

0.0274 |

0.0273 |

0.0269 |

0.0267 |

|

F/Chi 2-test |

245.4 |

49.38 |

246.9 |

290 |

147.2 |

33.53 |

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

F/Chi 2-test – equal coefficients |

5.417 |

18.20 |

4.397 |

|||

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 – equal coefficients |

0.000238 |

0.00113 |

0.00204 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

In addition, this regression also confirmed the rejection of the null hypothesis that all coefficients are equal, and here again, the composition of growth matters for the reduction of the share of vulnerable employment. There is a statistically significant negative coefficient of several specific sectors, in particular, construction and transport, storage and communication. Agriculture has a smaller negative coefficient, probably due to its higher labour intensity – and especially in lower-income countries with concentrations of low-productivity activities, for which it would need a stronger growth impulse. It also requires a transition from low- to higher-productivity activities (export-oriented agriculture, for example, tends to show higher formality rates). In addition, this seems to be a hard-to-handle sector for development policies from the institutional point of view in those countries. In any event, several studies indicate that due to the high labour intensity, this sector is critical for poverty alleviation (see, for example, Loayza and Raddatz 2010).27 In general, it also would be important to reflect on the role of the services sector in reducing informality because many developing countries rely on services.

Taking advantage of the large data set, we then decomposed the results by income level and by geographical regions. Table 4 shows the decomposition by income level for the fixed effects model. The first thing to note is that the overall effect of growth on the share of vulnerable employment (as a proxy of informality) grows with income level. It increases from -0.053 in low-income countries, from -0.136 in lower-middle-income countries, from -0.219 in upper-middle-income countries and from -0.231 in high-income countries.

More importantly, with enough observations for each group of income level in this data set, the null hypothesis of equality of sectoral coefficients is rejected in all income groups of countries, with at least an 85 per cent level of confidence. The coefficients for mining, manufacturing and utilities, and construction are statistically significant in all income groups of countries. However, several sectors that are relevant for each income group of countries varies because the specific characteristics of each sector differ with the level of economic development. For example, the coefficient of the other activities sector is significant in high- and upper-middle-income countries. The coefficient for agriculture is not significant in lower-middle and high-income countries, and the coefficient for trade, accommodation and food is significant in lower-middle and middle-income countries. The coefficient for transport, storage and communication is significant in upper-middle- and high-income countries.

Table 5 shows the results of the sectoral decomposition by geographical region. Here we confirm the most important results. First, the relationship between GDP growth and the reduction in the share of vulnerable employment (proxy for informality) exists but is different depending on region. In particular, the coefficient is small in Africa (at -0.087), but it is even smaller (at -0.31) in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Second, the null hypothesis that all coefficients are equal can be rejected except in Europe and Central Asia. Note, however, the same sectors that matter are not in all geographical regions. Agriculture is not statistically significant in all regions. On the contrary, mining, manufacturing and utilities is statistically significant and negative in all regions, while construction has a relevant negative coefficient, except in Latin America and the Caribbean, where it does not reach 90 per cent of statistical confidence (p-value of 0.117). The coefficient of trade, accommodation and food is significant in Latin America and the Caribbean, East and South Asia and the Pacific.28 Transport, storage and communication is a significant sector in Europe, Central Asia and Africa, while other activities have a lower statistically not-significant coefficient in Latin America and the Caribbean.

These results imply that it is the pattern of growth that matters and confirms that, for a given GDP growth rate, different sectoral patterns of growth could lead to different responses in the share of vulnerable employment (proxy for informality).

Finally, table 6 presents the evolution of this relationship over time. Recall that for the complete period from 1991 to 2019, the estimated coefficient of overall growth on the share of vulnerable employment (proxy of informality) is -0.157 (table 3). When we break down this estimation by subperiods, then we observe that the coefficient is lower from 1991 to 2000, at -0.107. But then it increases to -0.192 from 2001 to 2010, before decreasing again, to -0.146 in 2010–2019. Thus, the effect of growth on the informality rate (as measured by the share of vulnerable employment) is not constant over time. This can be seen clearly in figure A3 in the annex, where we show the estimated coefficients for overall growth over time. Although further research is needed, the specific stage of the business cycle (growth, crisis) in which the estimation is performed could be a key determinant for this finding.

Figure A4 in the annex disaggregates this finding even further using ventiles of income and confirms that the effect of economic growth on informality is not constant across income groups either. Overall, our estimated coefficient for the relationship between GDP and informality is -0.157, which means that GDP would have to grow around 6 per cent to reduce informality by 1 per cent. This relationship becomes more negative (the elasticity increases in absolute value) in middle-income countries and reduces again for high-income countries. This means that the same growth can have different impact on informality depending on the income level, probably due to the pre-existing levels of informality but also to other factors, such as the economic structure and the institutional frameworks.

Table 4. Regression: Share of vulnerable employment and composition of growth, by country group according to income level and using annual growth rates, 1991–2019

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

|

World |

Low income |

Lower-middle income |

Upper-middle income |

High income |

||||||

|

Variables |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects –overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.157*** |

-0.053*** |

-0.136*** |

-0.219*** |

-0.231*** |

|||||

|

(0.013) |

(0.009) |

(0.017) |

(0.020) |

(0.053) |

||||||

|

Agriculture |

-0.082*** |

-0.042*** |

-0.049 |

-0.199*** |

0.020 |

|||||

|

(0.021) |

(0.010) |

(0.040) |

(0.039) |

(0.328) |

||||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.157*** |

-0.076*** |

-0.168*** |

-0.162*** |

-0.223*** |

|||||

|

(0.015) |

(0.011) |

(0.023) |

(0.018) |

(0.057) |

||||||

|

Construction |

-0.265*** |

-0.120*** |

-0.217*** |

-0.325*** |

-0.466*** |

|||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.036) |

(0.053) |

(0.069) |

(0.121) |

||||||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.155*** |

-0.003 |

-0.140** |

-0.306*** |

-0.157 |

|||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.027) |

(0.061) |

(0.074) |

(0.117) |

||||||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.280*** |

-0.006 |

-0.163 |

-0.334*** |

-0.592** |

|||||

|

(0.064) |

(0.078) |

(0.108) |

(0.095) |

(0.237) |

||||||

|

Other activities |

-0.129*** |

-0.057** |

-0.105*** |

-0.171*** |

-0.164* |

|||||

|

(0.027) |

(0.025) |

(0.034) |

(0.043) |

(0.086) |

||||||

|

Constant |

-0.003*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.002*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.004*** |

-0.001*** |

-0.002*** |

-0.005*** |

-0.005*** |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

|

|

Observations |

4 796 |

4 792 |

714 |

713 |

1 309 |

1 309 |

1 324 |

1 324 |

1 449 |

1 446 |

|

Number of countries |

182 |

182 |

28 |

28 |

48 |

48 |

50 |

50 |

56 |

56 |

|

R-squared |

0.052 |

0.060 |

0.086 |

0.098 |

0.066 |

0.075 |

0.110 |

0.125 |

0.030 |

0.037 |

|

RMSE |

0.0269 |

0.0267 |

0.00913 |

0.00894 |

0.0204 |

0.0204 |

0.0282 |

0.0280 |

0.0349 |

0.0348 |

|

F-test |

147.2 |

33.53 |

36.19 |

19.69 |

64.87 |

16.08 |

124.2 |

42.29 |

19.20 |

8.501 |

|

Prob > F |

0 |

0 |

2.03e-06 |

1.06e-08 |

2.11e-10 |

5.98e-10 |

0 |

0 |

5.33e-05 |

1.53e-06 |

|

Test F – equal coefficients, all |

4.397 |

3.633 |

2.710 |

1.879 |

1.768 |

|||||

|

Prob > F – equal coefficients, all |

0.00204 |

0.0171 |

0.0412 |

0.129 |

0.148 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

Table 5. Regression: Share of vulnerable employment and composition of growth, by country group according to geographic region and using annual growth rates, 1991–2019

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

|

World |

Latin America and Caribbean |

East/South Asia and Pacific |

Europe and Central Asia |

Africa |

||||||

|

Variables |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects –sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects –overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.157*** |

-0.314*** |

-0.158*** |

-0.224*** |

-0.087*** |

|||||

|

(0.013) |

(0.050) |

(0.021) |

(0.023) |

(0.014) |

||||||

|

Agriculture |

-0.082*** |

-0.280* |

-0.049 |

-0.184*** |

-0.043*** |

|||||

|

(0.021) |

(0.155) |

(0.037) |

(0.030) |

(0.012) |

||||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.157*** |

-0.363*** |

-0.160*** |

-0.192*** |

-0.122*** |

|||||

|

(0.015) |

(0.079) |

(0.031) |

(0.023) |

(0.022) |

||||||

|

Construction |

-0.265*** |

-0.238 |

-0.207*** |

-0.319*** |

-0.189*** |

|||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.147) |

(0.042) |

(0.090) |

(0.052) |

||||||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.155*** |

-0.585*** |

-0.167*** |

-0.117 |

-0.041 |

|||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.139) |

(0.042) |

(0.117) |

(0.035) |

||||||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.280*** |

-0.184 |

-0.075 |

-0.482*** |

-0.116** |

|||||

|

(0.064) |

(0.337) |

(0.167) |

(0.138) |

(0.053) |

||||||

|

Other activities |

-0.129*** |

-0.080 |

-0.187*** |

-0.195*** |

-0.064* |

|||||

|

(0.027) |

(0.168) |

(0.057) |

(0.043) |

(0.037) |

||||||

|

Constant |

-0.003*** |

-0.003*** |

0.001* |

-0.000 |

-0.005*** |

-0.005*** |

-0.002*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.004*** |

-0.005*** |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Observations |

4 796 |

4 792 |

815 |

812 |

933 |

933 |

1 225 |

1 224 |

1 768 |

1 768 |

|

Number of countries |

182 |

182 |

30 |

30 |

34 |

34 |

48 |

48 |

68 |

68 |

|

R-squared |

0.052 |

0.060 |

0.097 |

0.110 |

0.070 |

0.076 |

0.057 |

0.069 |

0.044 |

0.053 |

|

RMSE |

0.0269 |

0.0267 |

0.0302 |

0.0300 |

0.0205 |

0.0205 |

0.0364 |

0.0362 |

0.0189 |

0.0188 |

|

F-test |

147.2 |

33.53 |

38.97 |

9.112 |

58.36 |

21.29 |

91.35 |

21.72 |

37.33 |

10.83 |

|

Prob > F |

0 |

0 |

8.21e-07 |

1.24e-05 |

8.56e-09 |

4.75e-10 |

0 |

0 |

5.71e-08 |

2.16e-08 |

|

Test F – equal coefficients, all |

4.397 |

1.941 |

3.310 |

0.519 |

4.791 |

|||||

|

Prob > F – equal coefficients, all |

0.00204 |

0.130 |

0.0219 |

0.722 |

0.00185 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

Table 6. Regression: Share of vulnerable employment and composition of growth, by decade and using annual growth rates, 1991–2019

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

|

|

1991–2019 |

1991–2000 |

2001–2010 |

2011–2019 |

|||||

|

Variables |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.157*** |

-0.107*** |

-0.192*** |

-0.146*** |

||||

|

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.021) |

(0.032) |

|||||

|

Agriculture |

-0.082*** |

-0.055*** |

-0.082*** |

-0.028 |

||||

|

(0.021) |

(0.014) |

(0.028) |

(0.050) |

|||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.157*** |

-0.108*** |

-0.209*** |

-0.107** |

||||

|

(0.015) |

(0.026) |

(0.027) |

(0.051) |

|||||

|

Construction |

-0.265*** |

-0.183*** |

-0.267*** |

-0.235** |

||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.057) |

(0.054) |

(0.094) |

|||||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.155*** |

-0.122** |

-0.189*** |

-0.259*** |

||||

|

(0.041) |

(0.047) |

(0.065) |

(0.085) |

|||||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.280*** |

-0.206*** |

-0.242* |

-0.060 |

||||

|

(0.064) |

(0.068) |

(0.125) |

(0.154) |

|||||

|

Other activities |

-0.129*** |

-0.068** |

-0.178*** |

-0.178** |

||||

|

(0.027) |

(0.031) |

(0.050) |

(0.074) |

|||||

|

Constant |

-0.003*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.001*** |

-0.002*** |

-0.003*** |

-0.004*** |

-0.005*** |

-0.005*** |

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

|

|

Observations |

4 796 |

4 792 |

1 511 |

1 510 |

1 721 |

1 718 |

1 564 |

1 564 |

|

R-squared |

182 |

182 |

179 |

179 |

181 |

181 |

181 |

181 |

|

Number of countries |

0.052 |

0.060 |

0.048 |

0.056 |

0.063 |

0.067 |

0.025 |

0.031 |

|

RMSE |

0.0269 |

0.0267 |

0.0206 |

0.0205 |

0.0257 |

0.0257 |

0.0264 |

0.0264 |

|

F-test |

147.2 |

33.53 |

65.53 |

15.86 |

83.62 |

18.05 |

20.86 |

4.567 |

|

Prob > F |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9.16e-06 |

0.000244 |

|

Test F – equal coefficients, all |

4.397 |

1.998 |

4.645 |

2.085 |

||||

|

Prob > F – equal coefficients, all |

0.00204 |

0.0968 |

0.00136 |

0.0847 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

Note that according to Anderton et al. (2014), the coefficients βs only represent the informality rate (here proxied by vulnerable employment) responsiveness of sector s to growth in a specific sector. To determine the full effect of a specific sector on GDP, we need also to include the relative weight of that sector in total GDP (λs = average share of GDP in sector s in time t). So, βs.λs represents the proportional responsiveness of informality (proxied by vulnerable employment) to changes in each sectoral component of GDP (component elasticities), and the sum of all these elasticities (∑βs.λst) should be roughly equivalent to the overall informal responsiveness to GDP. Therefore, using the estimated sectoral coefficient , we can estimate the elasticity of the impact of a 1 percentage-point increase in sector s as , where is average participation of sector s in time.

The result of this decomposition on vulnerable employment is shown in table 7. In this case, all sectors have statistically significant coefficients and negatively affect vulnerable employment. However, each sector contributes with different magnitudes. The largest contributor to the reduction of the share of vulnerable employment is other activities, which has an estimated coefficient of -0.129 and a higher relative weight in total GDP of 33.8 per cent. For this reason, its individual contribution to the overall effect is 27.7 per cent (-0.044/0.157). The second-most significant sector is mining, manufacturing and utilities, which has an intensity of 0.157 (similar to that corresponding to the total GDP), and its relative weight in total GDP is 22.6 per cent, so its contribution is also 22.6 per cent (-0.036/-0.157). Note that construction and transport, storage and communication have the highest estimated coefficients but their relative weights are smaller, with their contribution to the overall effect at 10.3 per cent and 15.3 per cent, respectively.

Table 7. Sectoral decomposition of the effect of GDP growth on share of vulnerable employment, 1991–2019

|

Intensity |

Sig. |

Average weight |

Component elasticity |

Estimated percentage contribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Agriculture |

-0.082 |

*** |

0.141 |

-0.012 |

7.4% |

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.157 |

*** |

0.226 |

-0.036 |

22.6% |

|

Construction |

-0.265 |

*** |

0.061 |

-0.016 |

10.3% |

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.155 |

*** |

0.155 |

-0.024 |

15.3% |

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.280 |

*** |

0.079 |

-0.022 |

14.1% |

|

Other activities |

-0.129 |

*** |

0.338 |

-0.044 |

27.7% |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.157 |

*** |

1.000 |

-0.157 |

100.0% |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Robustness checks

We next performed robustness checks to explore if our results persist using different methodological alternatives.

Testing for endogeneity

The first check was to control for possible endogeneity because production and employment are determined at the same time, and both variables could be influenced by similar factors not included in the estimated model. Although this model is reduced in our case because we controlled for fixed effects, we followed Anderton et al. (2014), and we performed a generalized method of moments approach in two stages. In particular, we used as instruments the lagged variables of the explanatory variables, which are not contemporaneous and therefore are not correlated with the dependent variable and are independent of the error in the regression. We used three lags for the overall growth regression and two lags for the sectoral growth specification – due to the more complex calculations in this case. And we followed Blundell and Bond’s (1998) suggestion to use as instruments only those values available in each moment to avoid losing degrees of freedom.

The results in table 8 indicate that the sectoral composition of growth is still statistically significant. All coefficients are significant, and the negative signs indicate that the coefficients are significantly different from each other. Therefore, the null hypothesis that all coefficients are equal is again rejected where we have used instruments. Also, the Hansen test – the J statistic and its p-value – indicate that this model is well specified and that the instruments are adequate.

Table 8. Generalized method of moments (GMM) model regression: Share of vulnerable employment and composition of growth using annual growth rates, 1991–2019

|

Variables |

GMM – overall |

GMM – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.190*** |

|

|

(0.016) |

||

|

Agriculture |

-0.062*** |

|

|

(0.005) |

||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.098*** |

|

|

(0.004) |

||

|

Construction |

-0.207*** |

|

|

(0.010) |

||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.210*** |

|

|

(0.017) |

||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.686*** |

|

|

(0.032) |

||

|

Other activities |

-0.122*** |

|

|

(0.010) |

||

|

Constant |

-0.002*** |

-0.002*** |

|

(0.001) |

(0.000) |

|

|

Observations |

4 796 |

4 792 |

|

Hansen J statistic |

87.43 |

177 |

|

P-value (Hansen test) |

0.195 |

0.443 |

|

RMSE |

0.0287 |

0.0287 |

|

Chi 2-test – equal coefficients, all |

193.2 |

|

|

Prob > Chi 2 – equal coefficients, all |

0 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT and UNdata.

An alternative definition: Informal GDP

A second check explored if our results hold even if we use another indicator of informality. So far, we have explored two indicators: the share of informal employment and the share of vulnerable employment. The employment dimension is important but it is only one dimension of this concept. For this reason, we explored another dimension of informality related to informal productive activities, or informal production, as a proxy of this contribution.

We ran the same regressions as before, and the results are presented in table 9. The dependent variable is the proportion of GDP that is informal, as measured by the size of the shadow economy, which Medina and Schneider (2019) estimated using an indirect approach based on the multiple indicator–multiple cause.29 We observed that the overall GDP effect is statistically significant and negative around -0.28 and -0.33. In the regression on sectoral composition of GDP, again we found negative significant coefficients (except in the case of other activities). The Hausman test indicates that the fixed effects model is preferred. More importantly, the test of equality of parameters is rejected again, confirming that our results still hold even when we use an alternative measure of informality.30

Table 9. Regression: Size of the shadow economy and composition of growth using annual growth rates, 1991–2017

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

|

|

Variables |

Random effects – overall |

Random effects – sectoral |

Fixed effects – overall |

Fixed effects – sectoral |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.279*** |

-0.337*** |

||

|

(0.018) |

(0.020) |

|||

|

Agriculture |

-0.116*** |

-0.145*** |

||

|

(0.045) |

(0.047) |

|||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.322*** |

-0.378*** |

||

|

(0.035) |

(0.037) |

|||

|

Construction |

-0.545*** |

-0.611*** |

||

|

(0.081) |

(0.085) |

|||

|

Trade, accommodation and food |

-0.518*** |

-0.564*** |

||

|

(0.059) |

(0.062) |

|||

|

Transport, storage and communication |

-0.789*** |

-0.917*** |

||

|

(0.131) |

(0.137) |

|||

|

Other activities |

0.110** |

0.072 |

||

|

(0.045) |

(0.048) |

|||

|

Constant |

-0.006*** |

-0.007*** |

-0.005*** |

-0.006*** |

|

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

|

|

Observations |

3 828 |

3 823 |

3 828 |

3 823 |

|

Number of countries |

156 |

156 |

156 |

156 |

|

R-squared |

0.071 |

0.098 |

||

|

RMSE |

0.0395 |

0.0390 |

0.0398 |

0.0393 |

|

F/Chi 2-test |

249.9 |

367.1 |

281.5 |

66.57 |

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

F/Chi 2-test – equal coefficients, all |

104.3 |

26.07 |

||

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 – equal coefficients, all |

0 |

0 |

||

|

F/Chi 2-test – equal coefficients, agriculture and trade |

28.59 |

28.94 |

||

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 – equal coefficients, agriculture and trade. |

8.95e-08 |

7.93e-08 |

||

|

F/Chi 2-test – equal coefficients, other sectors |

79.50 |

39.67 |

||

|

Prob > F/Chi 2 – equal coefficients, other sectors |

0 |

0 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***=p<0.01, **=p<0.05, *=p<0.1.

Source: ILOSTAT, UNdata and Medina and Schneider database.

Taking into account institutional variables

Finally, there is also a possibility that our results could be influenced by other variables affecting the relationship between informality and growth. As mentioned in the literature review section, the literature has given important attention to the role of institutional variables. Thus, we ran our estimates again, controlling for variables associated with the legal or institutional settings.

The results of this exercise are shown in table 10, for the case of vulnerable employment as a dependent variable.31 For the institutional variables, we included the following variables that were used in the related literature previously reviewed:

-

The ILO Employment Protection Legislation Index (EPLex), which is a weighted average of nine indicators in five areas: substantive requirements for dismissal, maximum probationary period, procedural requirements for dismissals, severance and redundancy pay, and avenues for redress.32 Annual data are available for 103 countries from 2000 to 2020.

-

The components of hiring and firing practices and wage flexibility within the Global Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum (Schwab 2019). Annual data are available for 152 countries from 2007 to 2019.

-

The Economic Freedom of the World Index by the Fraser Institute (2019), which combines measures in five areas: size of government, system and property rights, sound money legal, freedom to trade internationally and regulation. Annual data are available for 165 countries for 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995 and from 2000 to 2019.

-

The Index of Economic Freedom estimated by The Heritage Foundation using four categories: rule of law, government size, regulatory efficiency and open markets. Annual data are available for 184 countries from 1995 to 2019.

-

The law and order component of the Political Risk Index of the International Country Risk Guide by the Political Risk Services Group. To assess the “law” element, the strength and impartiality of the legal system were considered, while the “order” element is an assessment of popular observance of the law. Annual data are available since 1984 until 2020 for 145 countries.

-

The corruption within the political system component of the Political Risk Index of the International Country Risk Guide by the Political Risk Services Group.

First, we included variables associated with labour market regulations – employment protection, hiring and firing and flexibility in wage determination. Those variables did not affect our estimated results and turned out to be statistically non-significant.

We then included the variable associated with economic freedom, and this inclusion does not affect our results either, except for a small decrease in the magnitude of the coefficients of economic growth. The coefficients of the Heritage Foundation index are positive and statistically significant at 5 per cent and the positive coefficient of the Fraser Institute index turns out to be statistically significant at 10 per cent but only for the sectoral growth regression and not for the overall growth specification. We did not find the respective coefficients statistically significant in the regressions using informal employment and, in that case, they have a negative sign. Because both indicators relate more to regulations in the product markets, these results could mean that the type of regulation of economic activities has a role in the evolution of informality – measured as vulnerable employment. But this specific topic requires further research.

Then we included the index of law and order, which measures the ability of states to implement regulations. Here again our results hold, and this variable turn out to be non-significant. Finally, we also included an indicator of corruption as measured by the component of corruption of the International Country Risk Guide. Again, our results hold, and this variable turns out to be statistically non-significant.

To sum up, our results remained valid after including different institutional variables, and most of them turned out to be statistically non-significant when we correlated variations in informality with variations in economic and institutional variables. The exception is the Economic Freedom Index for the vulnerable employment, although it was not statistically significant when we used the informal employment definition. These results could differ from other studies regarding institutional variables in the sense that our analysis used variations while most studies run their econometric estimations using levels of the variables. Typically, institutional variables do not have much variation as informality has, which can help explain these results. Another important difference is that – by definition – our estimation also controlled for sectoral growth. In any case, this exercise allows us to confirm that our findings on the importance of the economic structure on the evolution of informality was not altered after the introduction of institutional variables.

Table 10. Regression controlling for institutional factors: Share of vulnerable employment and composition using annual growth rates

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

(12) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

Panel |

|

|

Variables |

Fixed effects – global growth and employment protection legislation |

Fixed effects – sectoral growth and employment protection legislation |

Fixed effects – global growth and labour flexibility |

Fixed effects – sectoral growth and labour flexibility |

Fixed effects – global growth and economic freedom – Fraser Institute |

Fixed effects –sectoral growth and economic freedom – Fraser Institute |

Fixed effects –global growth and economic freedom–Heritage Foundation |

Fixed effects – sectoral growth and economic freedom– Heritage Foundation |

Fixed effects – global growth and law and order |

Fixed effects – sectoral growth and law and order |

Fixed effects – global growth and corruption |

Fixed effects – sectoral growth and corruption |

|

Total gross value added |

-0.204*** |

-0.224*** |

-0.177*** |

-0.179*** |

-0.141*** |

-0.140*** |

||||||

|

(0.054) |

(0.033) |

(0.023) |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

|||||||

|

Agriculture |

-0.025 |

-0.108 |

-0.053 |

-0.064** |

-0.013 |

-0.014 |

||||||

|

(0.093) |

(0.066) |

(0.039) |

(0.028) |

(0.023) |

(0.023) |

|||||||

|

Mining, manufacturing and utilities |

-0.159** |

-0.186*** |

-0.161*** |

-0.177*** |

-0.145*** |

-0.144*** |

||||||

|

(0.073) |

(0.041) |

(0.032) |

(0.023) |

(0.024) |

(0.024) |

|||||||

|

Construction |

-0.263 |

-0.326*** |

-0.266*** |

-0.323*** |

-0.292*** |

-0.292*** |

||||||

|

(0.169) |

(0.091) |