How corporate social responsibility and sustainable development functions impact the workplace: A review of the literature

Executive Summary

This report sets out to analyse the emergence and distinctive impact of corporate social responsibility and sustainable development (CSR/SD) functions and professionals within organizations. By evaluating the literature on this topic, it seeks to clarify how leveraging the already established CSR/SD functions and professionals across organizations can contribute to the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) objective of achieving a future of work that provides decent and sustainable work opportunities for all. An extensive and integrative review of the academic literature was undertaken and an interview with a panel of academic experts conducted in order to highlight various aspects of CSR/SD functions and professionals. The focus was on three core topics: the embedding of CSR/SD functions and professionals (Topic #1); their role in managing stakeholder relations (Topic #2); and, more specifically, their contribution to the shaping of interactions with employees and trade unions (Topic #3).

While CSR and SD have different historical roots, the two concepts overlap significantly. The umbrella term “CSR/SD” is therefore used throughout the report. “CSR/SD” itself is defined as encompassing corporate interactions with society and in particular with the multiple stakeholder groups from the corporate environment. “CSR/SD professionals” are defined as organizational actors either working within CSR/SD functions or whose role and activities at least have to do with managing CSR/SD issues. These functions are not a new phenomenon: a first wave emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Renewed managerial interest in CSR/SD matters triggered the second wave in the 1990s, which was, paradoxically perhaps, strengthened by the 2008 financial crisis.

Introduction

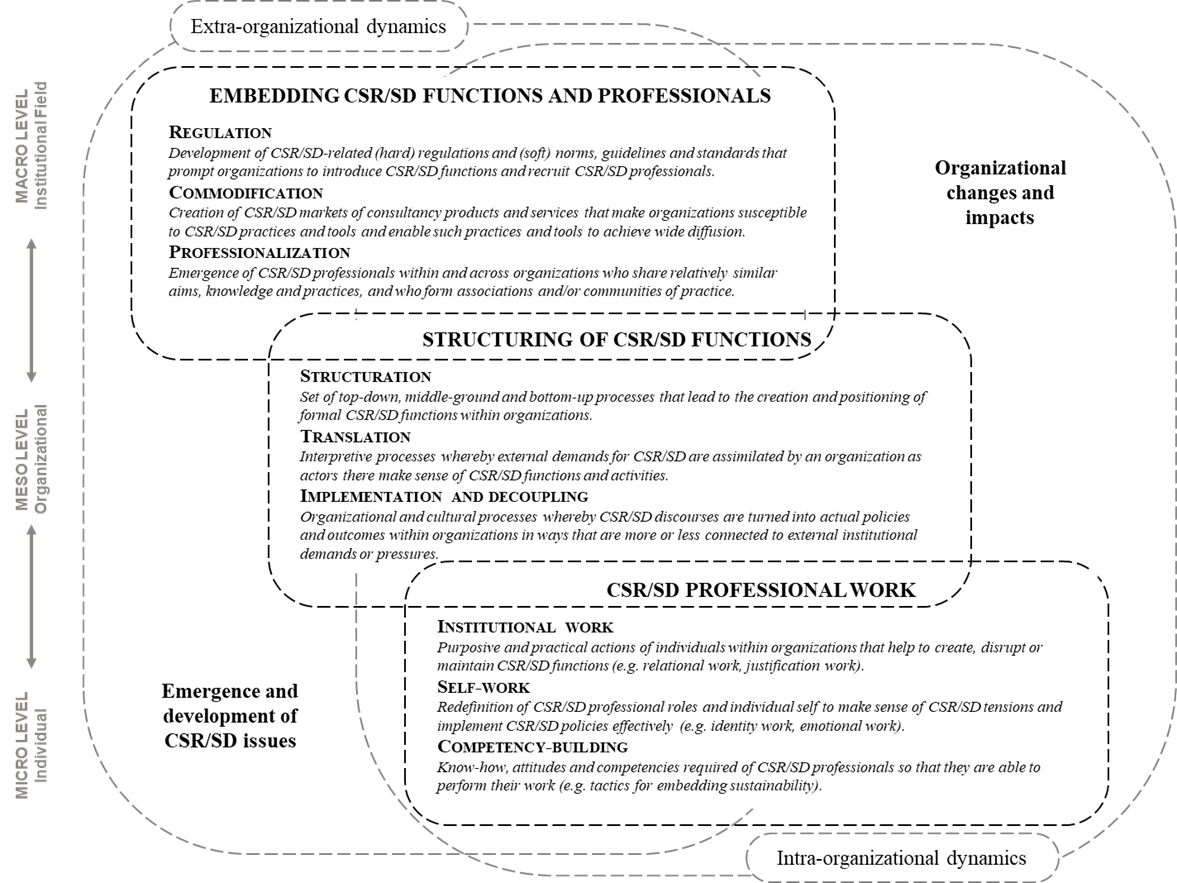

What do we know? A boundary-process framework

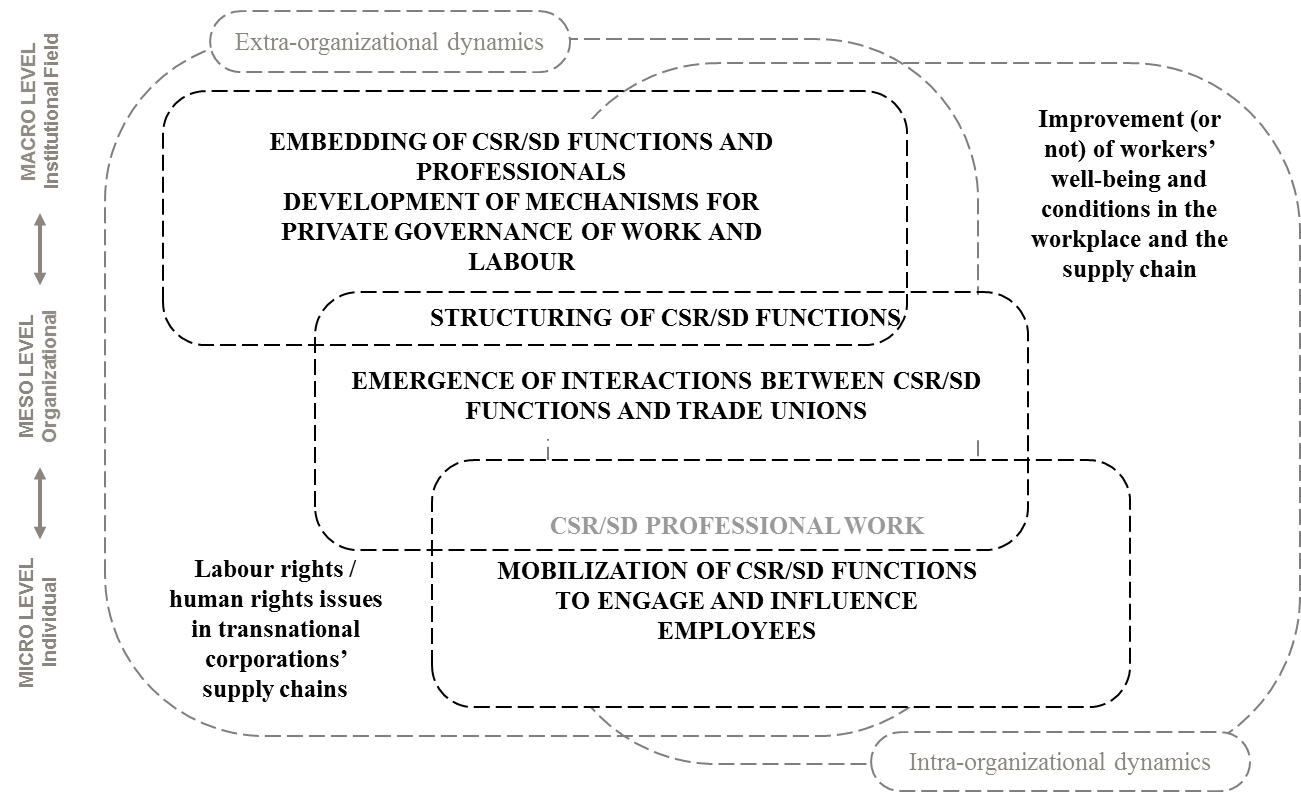

Recognizing that a core characteristic of CSR/SD functions and professionals is their location at the interface of organizations and their environments, this report adopts the notion of a “boundary process” – that is, a process linking internal and external political dynamics – in order to survey the academic literature and organize it into a coherent framework (as presented in Figure 1). This framework integrates analysis at the individual, organizational and institutional field levels. An institutional field is defined as sets of organizations that together constitute an institutional domain (in our case, the CSR/SD domain); these may involve not only corporations, but also their suppliers, consumer associations, labour unions, consultancy organizations and multiple types of regulatory agencies (see DiMaggio and Powell 1983).

Embedding CSR/SD functions and professionals

This framework was first used to study the mechanisms responsible for the embedding of CSR/SD functions and professionals across the different levels considered in this report. At the macro level, broad regulatory, market and professionalization dynamics foster the development of CSR/SD functions and create a need for CSR/SD professionals within organizations. Three trends may be identified in that respect:

-

Regulation: A global increase in legislation contributes to the expansion of CSR/SD functions and to the professionalization of this institutional field. This is supported by non‑governmental standards, which encourage a culture of self-reflection within organizations and thus promote CSR/SD.

-

Commodification: Environmental and social issues have been turned into commodities sold by consultancy firms on the CSR/SD market. Consultancies across the world raise awareness of and “translate” regulations and standards, often bringing together companies from different industries to share best practices. These consultancies reshape the meaning of CSR/SD and reinforce a business case rhetoric when it comes to the adoption of CSR/SD practices by organizations.

-

Professionalization: The increasing professionalization of CSR/SD involves the establishment of informal and formal communities of practice, which may sometimes take the form of professional associations. In addition to serving as a platform for CSR/SD practitioners, these also draw up standards and provide certification for their members. Such networks of practitioners equip their members with shared knowledge and a common identity and purpose; they are largely characterized by passion for their work. However, the professionalization of the CSR/SD institutional field raises certain questions, such as the lack of a clearly defined CSR knowledge base, the multiple meanings attached to CSR, the absence of clear boundaries in the institutional field, and the marginalization of the work of CSR/SD practitioners.

At the meso level of analysis, it has been pointed out that the organizational‑level deployment of CSR/SD functions takes place through structuring, translation and implementation/decoupling. Scholars are divided as to whether CSR/SD functions are condemned to marginalization or are a necessary step in the transition towards a sustainable future. The focus of research has been on:

-

Structuring: A number of studies have looked at the structuring of CSR/SD functions from “top‑down”, “bottom‑up” or “middle-focused” perspectives. A top-down approach concentrates on how CSR/SD positions in senior management influence CSR/SD performance depending on the regulatory environment, previous performance, and an organization’s choice of chief sustainability officer, where efforts are more substantive than symbolic. The bottom-up approach investigates employees’ involvement in the successful implementation of CSR/SD across the organization. It is the middle manager who is often tasked with implementing CSR/SD strategies, despite not having sufficient authority or discretion and being in the midst of “turf wars” with other areas of the organization, such as human resources.

-

Translation: CSR/SD functions are not a passive audience of social and environmental issues but actively interpret and translate these issues, as a result of which they also neutralize them. This may lead to routine solutions that are unlikely to address the issues successfully.

-

Implementation and decoupling: How CSR/SD is implemented within an organization is also related to CSR/SD functions. Different stages of organizational “maturity” about CSR/SD will influence the size and expertise of these functions, as well as their relationships with other functions. The legitimacy of the functions is reflective of the ability of practitioners to achieve further maturity within their organization. CSR/SD functions play a role in managing potential gaps between organizational policies and discourses on the one hand, and practices on the other (as in the case of “greenwashing”). Studies have found that companies go through cycles of wider and narrower gaps, and that an initially wide gap can lead to discourses and practices that are more aligned. This is confirmed by studies which suggest that corporate hypocrisy can be helpful in triggering further action through aspirational talk, behind‑the-scenes work and irony. Nowadays, studies documenting gaps are gradually being replaced by examinations of the actual impact achieved by CSR practices.

Lastly, at the micro level of analysis, research has documented how individuals shape CSR/SD functions through their roles and everyday tasks, as played out through:

-

Institutional work: The purposive actions undertaken by individuals within organizations to sustain CSR/SD-related institutions, such as activities aimed at making CSR or SD part of corporate strategy.

-

Self-work: The reflexive work of CSR/SD employees to define their new professional identities and deal with the emotionally loaded aspects of their roles.

-

Competency-building: The acquisition of the requisite skills, know-how and forms of behaviour that can help ensure that CSR/SD is implemented successfully within organizations.

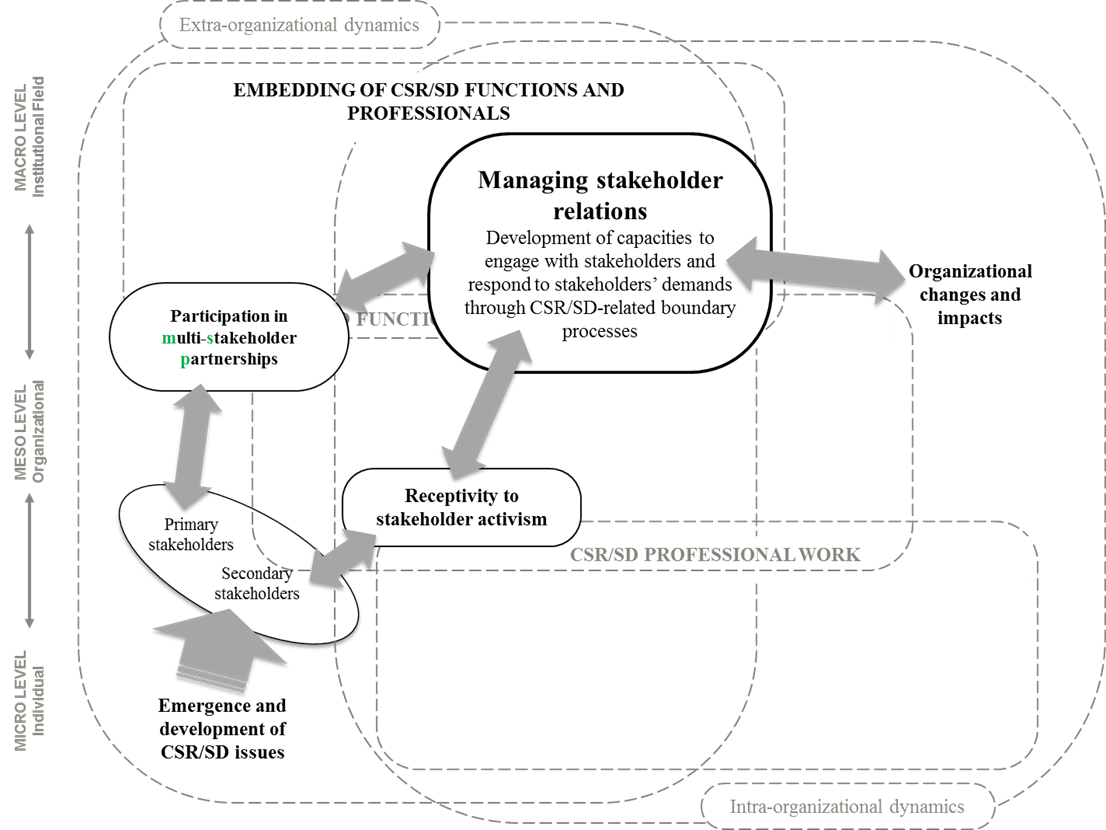

Managing stakeholder relations through CSR/SD boundary processes

The boundary-process framework was next used to analyse the external stakeholder pressures on CSR/SD functions and the various relationships that these functions create with stakeholders. The present literature review suggests that both confrontation (activist targeting) and collaboration (partnership) are effective processes for CSR/SD adoption and change:

-

Confrontation – Dealing with external stakeholder pressure: Research shows that companies are more likely to adopt CSR/SD structures and practices if they are targeted by activist shareholders. Companies tend to be influenced more by their primary stakeholders (employees, investors, customers and governments) than by their secondary ones (such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the media). Activist campaigns by secondary stakeholders tend to be more successful if they are stigmatizing and reputationally threatening, especially if the company has made previous CSR commitments and claims. This may lead to companies hiding sustainability credentials to avoid being labelled as hypocritical. However, research also suggests that, even if companies make only a small initial commitment, this can grow into more substantive change as they become more responsive to activist targeting.

-

Collaboration – Managing stakeholder relations through multi-stakeholder partnerships: Studies have found that the involvement of third parties substantially improves the relationship between business and civil society in partnerships. Effectiveness is further improved by distributed decision-making, conflict resolution procedures and controlling the size of partnerships. However, as companies mature in their engagement and move towards a proactive sustainability strategy, they may become less responsive to issues that they deem to fall outside the scope of that strategy.

Shaping interactions with employees and trade unions through CSR/SD boundary processes

Lastly, the boundary-process framework was used to analyse the relationships between labour issues and employees and CSR/SD functions at the macro, meso and micro levels. At the macro level, research has highlighted the rise of private governance of work- and labour-specific CSR/SD and soft regulations initiated by transnational companies or transnational multi‑stakeholder platforms, focusing in particular on:

-

The institutionalization of private governance throughout companies’ supply chain networks and through the development of codes of conduct, international framework agreements and supplier programmes.

-

The conditions shaping the effectiveness and social impact of soft regulations on companies’ supply chains: Studies dealing with this aspect suggest that the social impact of soft regulations remains limited, owing to the competitive environment, the pressure to deliver, the lack of union and worker involvement in the development and implementation of standards, vague measurement indicators, and national constraints on democratic unionism. Nevertheless, studies have highlighted a few examples of trade unions being successfully involved in global production networks and the local implementation of standards.

-

The outcome of private governance processes: Research shows that codes of conduct for supply chains increase demand for transparency and enhance global coordination across an industry. The impact of private governance is also influenced by the interdependence of stakeholders and the development of shared norms.

At the meso level, the present review shows that studies have focused on trade unions and, in particular, on:

-

The participation of workers and unions in the development of private governance: Although this participation is assumed to be limited, studies have showcased a number of relevant best practices. Unions could play a key role in developing these standards and monitoring their implementation.

-

The interactions of trade unions with CSR/SD functions and professionals: There is evidence of trade unions driving the adoption of CSR/SD functions and practices through either collaboration or increased pressure. The degree of unionization influences the orientation of corporate CSR/SD policies. Unions may partner with NGOs to maximize their impact.

-

The social responsibility of unions themselves: Some studies have focused on the positive impact of social responsibility on employees’ engagement with trade unions. This impact is analysed in the context of the multi-stakeholder interactions between local governments, NGOs, companies and other unions.

Lastly, at the micro level of analysis, the literature reflects the following trends:

-

Studies tend to focus on employee perceptions of CSR/SD, rather than on employees’ level of engagement with CSR/SD programmes. Where they focus on employee engagement, this process is described as encompassing transactional, relational and developmental components.

-

A large number of boundary conditions which shape employees’ reactions to CSR/SD have been identified, such as the ethical climate, the culture, the prevalent type of leadership and job-related factors (for example, job security).

-

Studies have pointed to numerous employee-level outcomes of CSR/SD, showing, in particular, the positive behavioural, attitudinal and cognitive changes arising from enhanced perceptions of CSR/SD. However, some authors have also warned that more research needs to be undertaken on the potential dark side of CSR/SD policies and programmes, which could be turned into mechanisms of ideological control.

Where should we go from here? Four challenges and a research agenda

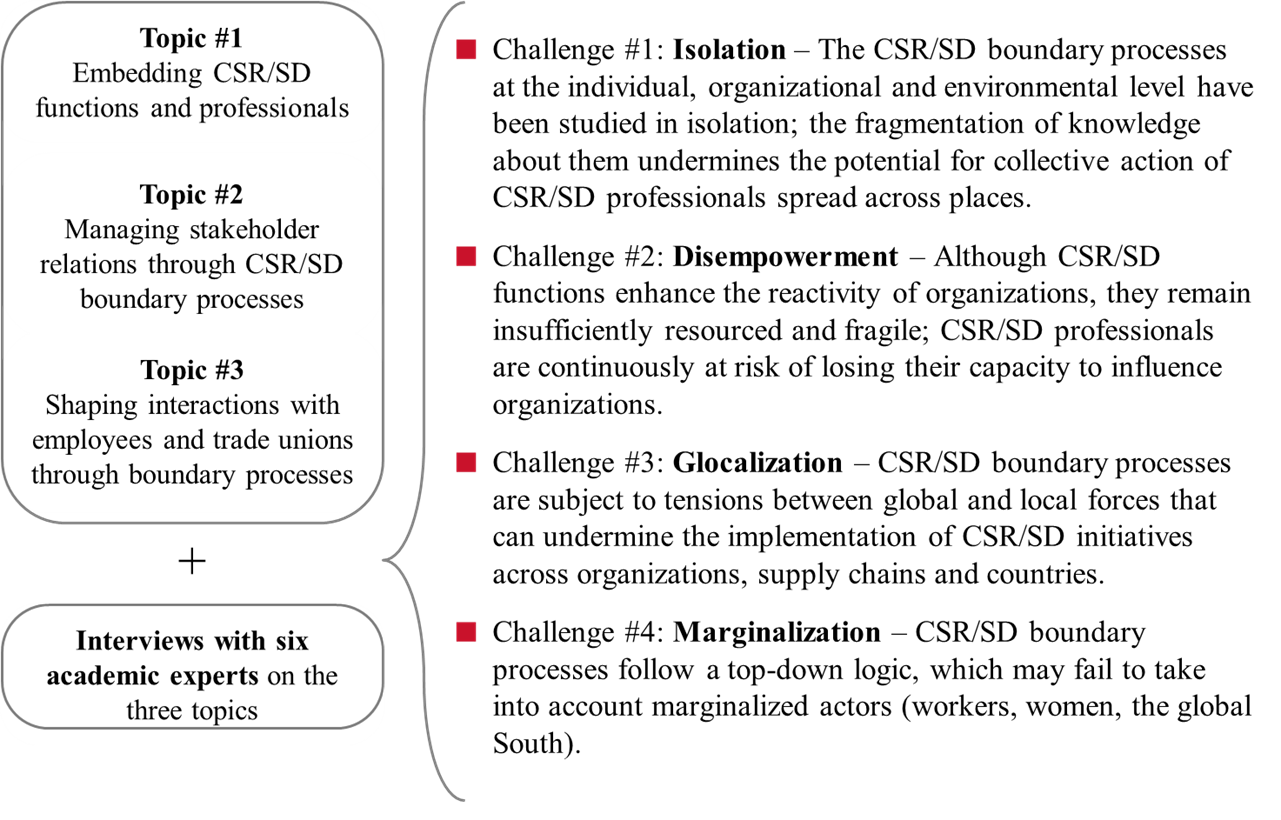

Using the insights gained from a systematic review of the literature based on the boundary‑process framework, together with interviews with a panel of six academic experts about the key topics covered, this report identifies four current challenges:

-

Isolation: The CSR/SD boundary processes at the individual, organizational and institutional field levels have been studied in isolation; the fragmentation of knowledge about them undermines the collective action of CSR/SD professionals.

-

Disempowerment: Although CSR/SD functions and the related boundary processes enhance the reactivity of organizations, they remain insufficiently resourced and fragile; CSR/SD professionals are continuously at risk of losing their capacity to influence organizations.

-

Glocalization: CSR/SD boundary processes are subject to tensions between global and local forces that can undermine the implementation of CSR/SD initiatives across organizations, supply chains and countries.

-

Marginalization: CSR/SD boundary processes follow a top-down logic, which may fail to take into account marginalized actors (such as workers, women and the global South).

To tackle these challenges, a research agenda is proposed with four key priorities:

-

Research direction #1: Bridging CSR/SD boundary processes vertically – to clarify how CSR/SD functions and professionals operate at the institutional field (macro), organizational (meso) and individual (micro) levels of analysis – and horizontally – by clarifying how processes such as professionalization and the emergence of communities of practice interact. This could help consolidate and expand current knowledge. Specifying and leveraging these connections could make CSR/SD functions and professionals much more effective at helping organizations tackle CSR/SD issues.

-

Research direction #2: Reconsidering temporal dynamics in the analysis of how CSR/SD boundary processes are formed within organizations and operate across multiple organizations. This could help make these processes better able to shape CSR/SD‑related outcomes.

-

Research direction #3: Exploring and harnessing the regulatory potential of CSR/SD boundary processes. Future research could focus on dynamics for mobilizing, empowering and/or developing the vast networks of CSR/SD experts and professionals with a view to regulating CSR/SD indirectly. Such studies could help evaluate the effectiveness of various forms of soft and hard regulation related to CSR/SD functions and experts.

-

Research direction #4: Redesigning CSR/SD boundary processes to take better account of marginalized voices, for instance by developing research methodologies that are able to reach workers in long supply chains who may struggle to make their concerns heard. This also calls for attention to be refocused on the global South and on hidden aspects of supply chains.

Implementing such a research agenda will require multi-methods designs (for example, combining ethnography and quantitative analyses) and novel empirical methods (such as fuzzy‑set qualitative comparative analysis). This endeavour is likely to benefit from innovative forms of cooperation between researchers and a variety of stakeholders, such as governments, private corporations, standard-setting organizations and trade unions.

|

To conclude, CSR/SD functions and professionals have considerable potential for resocializing organizations into their political, social and ecological environment, but this potential is far from fully realized. The research directions offered in this report seek to maximize the contribution of CSR/SD functions and professionals to the development of organizations’ capacity to tackle major challenges such as climate change, the loss of biodiversity, and the protection of labour and human rights along extended transnational supply chains. |

Research background, definitions and methodology

After presenting the background to the research (1.1), the definitions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development (SD) used in this report are specified and the research undertaken is put into context (1.2). Finally, the methodology underlying the literature review is outlined (1.3).

1.1. The continuous rise of interest in corporate social responsibility and sustainable development in the light of contemporary challenges

Although the notion that businesses should treat their constituents responsibly and show some consideration for the ecological environment on which they rely is probably as old as the capitalist system itself (Bowen 1953), over the past 30 years there has been an unprecedented upsurge in interest in CSR and SD across managerial and political spheres at local, national and transnational levels. Both concepts have to do with organizations’ relationships with their key stakeholders and point to “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” (Aguinis 2011, 855). Several factors have driven the continuous rise of interest in CSR and SD, often referred to as the “mainstreaming” of these two concepts, in particular the following four trends:

-

CSR and SD “strategifying” (Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian 2018*)1, that is, the progressive recognition, in the academic field of strategy and in the managerial world, that CSR and SD should and do form an integral part of organizations’ strategies. This trend is related to the embracing of CSR by influential scholars such as Michael Porter (Porter and Kramer 2006; 2011) and the emergence of a vast “business case” literature (Carroll and Shabana 2010) focused on establishing how CSR and SD initiatives can pay off for corporate actors by strengthening their competitiveness or reshaping the attitudes and behaviours of their stakeholders (for a meta-analysis, see Vishwanathan et al. 2020). The fact that CSR and SD have become frequent topics of discussion in boardrooms and are raised by institutional investors at general assemblies testifies to the strategic mainstreaming of these two concepts.

-

CSR and SD materialization, that is, the emergence and development of an extensive material infrastructure of standards, metrics, reporting, insurance procedures and business frameworks designed to support practitioners working in the domains of CSR and SD (Gond and Nyberg 2017; Waddock 2008). This material infrastructure is underpinned by regulations and by the institutionalization of CSR and SD as markets – the “markets for virtue” (Vogel 2005) that have been resilient to shocks as severe as the global financial crisis of 2007–08 and the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic of 2020.

-

CSR and SD globalization, which reflects the increased and continuous flows of workers and goods across borders and the outsourcing of multinational corporations’ (MNCs) activities across long supply-chains that cut across geographical borders – at least until the COVID-19 pandemic. CSR and SD globalization is also related to financialization, as a growing number of institutional investors export CSR and SD standards from developed (mainly Western) countries to other parts of the globe through the pressure they exercise on their investee companies across multiple financial markets.

-

CSR and SD politicization, which is captured by frameworks such as Matten and Moon’s (2008) distinction between “implicit” and “explicit” CSR, or Matten and Crane’s (2005) analysis of “corporate citizenship”. These frameworks show how institutional contexts shape local and political understanding of CSR. They also highlight the blurring of boundaries between the roles of governments and MNCs, turning de facto private organizations into political actors (Scherer and Palazzo 2011). CSR politicization has turned into a research field in its own right – referred to as “political CSR” – and has led to studies looking at the role of governments in relation to CSR and SD (see, for example, Knudsen and Moon 2017; Kourula et al. 2019).

All these trends have contributed to CSR and SD becoming firmly embedded within organizations. One of the most salient illustrations of this is the enduring institutionalization of CSR and SD functions and the sustained growth in the number of CSR and SD professionals. Tellingly, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an explosion in CSR/SD initiatives by leading economic players and corporations all over the world with the aim of supporting local communities and hospitals, facilitating the production of essential products such as masks or hydroalcoholic gels, reconverting production lines and designing new components to help to manufacture ventilators, and protecting the health and safety of workers (Aguinis, Villamor and Gabriel 2020). Organizations have leveraged earlier CSR/SD initiatives or designed new ones from scratch in an attempt “to do the right thing”. Admittedly, some of these initiatives have backfired; for example, Amazon’s expansion of its online grocery delivery platform to provide people living in confinement with essential services and the donation of US$100 million to food banks in the United States of America by its chief executive (Amazon 2020) could not prevent criticism of the poor safety conditions provided for the company’s logistics workers (Aguinis, Villamor and Gabriel 2020).

The example of Amazon illustrates the complexities, potentialities and limitations of the roles that CSR and SD functions and professionals are able to play. It serves as a reminder that the rise of CSR/SD functions and professionals also triggers legitimate questions about their actual impact in the workplace and within the broader environmental and social context of organizations. This report sets out, accordingly, to review studies of what impact CSR and SD functions and professionals have on the workplace.

1.2. Defining CSR/SD functions and contextualizing their emergence

The review undertaken for this report focuses on the development, within organizations, of functions and professionals dedicated to the management of CSR and SD, and on the impact of these functions and the associated practices on employees and working conditions. Although the concepts of CSR and SD have distinct historical roots,2 they overlap significantly since they may both be defined broadly as encompassing corporate interactions with society and the ecological environment, channelled through multiple stakeholders. Table 1 provides a selection of academic and practice-based definitions of CSR and SD that illustrates the overlaps between the two concepts.

Table 1. Academic and practice-based definitions of CSR and SD

|

Corporate social responsibility |

Sustainable development |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Academic definitions |

Hillman and Keim (2001) |

A broad construct comprised of stakeholder management and social issue management. |

Hart (1995) |

A sustainable development strategy, however, also requires that efforts be made to counter the negative effects of economic activity on the environment in the developing countries of the global South. |

|

McWilliams and Siegel (2001) |

Actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law. |

Russo (2003) |

An ecologically sustainable industry is a collection of organizations with a commitment to economic and environmental goals, whose members can exist and flourish (either unchanged or in adapted forms) for lengthy periods of time such that the existence and flourishing of other groups of entities can take place at related levels and in related systems. |

|

|

Flammer (2013) |

While the original focus of CSR was on “social” responsibility (e.g. paying fair wages to employees, community-based programmes), a recent development is its expansion to cover environmental responsibility (e.g. the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions). |

Bansal (2005) |

Three conditions need to be fulfilled in order to achieve sustainable development: environmental integrity, economic prosperity and social equity. |

|

|

Practice-based definitions |

BSR (2003) |

Achieving commercial success in ways that uphold ethical values and respect people, communities and the natural environment. CSR also means addressing the legal, ethical, commercial and other expectations that society has of businesses, and making decisions that fairly balance the claims of all key stakeholders. |

WCED (1987) |

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. |

|

ILO (n.d.) |

CSR is a way in which enterprises take into consideration the impact of their operations on society and affirm their principles and values both in their own internal methods and processes and in their interaction with other actors. CSR is a voluntary, enterprise-driven process and refers to activities that are considered to go beyond mere compliance with the law. |

ISO (2012) |

The notion of sustainable development is based on the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992), and it encompasses the concepts of intergenerational equity, social cohesion, human well-being and international responsibility; its implementation is intended to lead to sustainability. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) uses the definition from the Brundtland Report (WCED 1987): “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” |

|

|

European Commission (2019) |

The responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society. To fully meet their social responsibility, companies should have in place a process to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders, with the aim of maximizing the creation of shared value for their owners/shareholders and civil society at large and identifying, preventing and mitigating possible adverse impacts. |

European Commission (n.d.) |

Sustainable development means meeting the needs of the present while ensuring that future generations can meet their own needs. It has three pillars: economic, environmental and social. To achieve sustainable development, policies in these three areas have to work together and support one another. |

By means of a systematic review of articles published in mainstream journals between 1995 and 2014, Bansal and Song (2017) provide evidence of the considerable blurring of boundaries between CSR and SD research, at both the conceptual and measurement levels, and also in relation to the analysis of the antecedents and impacts of CSR and SD. Practitioner-focused journals such as Harvard Business Review, California Management Review or MIT Sloan Management Review refer alternatively, and sometimes interchangeably, to one or the other of the two concepts, suggesting a similar blurring of their definitions in practice. In the case of corporate reporting on non-financial information, it can be seen how these labels are used interchangeably (as in Royal Dutch Shell’s Sustainability Report or JP Morgan’s Corporate Responsibility Report). This report therefore adopts the umbrella term “CSR/SD” to refer to the functions and professionals in question, and considers articles published in both CSR-focused journals (such as Business & Society) and sustainability-focused journals (such as Organization & Environment), where authors may refer to one or the other notion.

The definition of CSR/SD functions used here is broad and includes any formal organizational unit in charge of CSR- and SD-related domains and/or responsible for more specific social and environmental issues. CSR/SD functions may involve only one actor, and their degree of formalization and structuring may vary widely, as may their prerogatives, levels of empowerment and authority, and positioning within organizations (for example, direct reporting to the board, or dedicated CSR/SD board members). Prior research has found that CSR/SD functions can arise from already established functions, such as public relations or human resource departments, and can contribute to the emergence of new coordination challenges by reshaping functional boundaries (Gond, Igalens, Swaen and El-Akremi 2011*). A similarly broad approach is taken in this report when defining CSR/SD professionals: these are considered to be any organizational actors working within such functions, or whose role and daily activities are at least partly taken up with the handling of CSR/SD issues. As with CSR/SD functions, these roles are subject to potential conflicts of task ownership and authority, since CSR/SD activities may significantly overlap with other occupations and professional jurisdictions (Abbott 1988).

Although the focus in this report is on the literature published in the past 20 years, the emergence of CSR/SD functions in organizations began considerably earlier. Howard R. Bowen (1953, 155) could already foresee such a development in the early 1950s:

-

[…] perhaps, some day, a new official known as the “manager of the department of social responsibility” might be created to coordinate the activities of the various officials who represent various aspects of the public interest.

In fact, when synthetizing the findings of a two-year research project conducted at Harvard Business School (1972–74) that included case studies of how 40 US corporations were dealing with social issues, Ackerman and Bauer (1976) pointed to the emergence of new functional departments and professionals in charge of such issues. They identified some of the tensions inherent in corporate appropriation of this new domain and in the design of relevant functions (Ackerman 1973). Acquier (2016) interprets this first wave of institutionalization of CSR/SD functions as resulting from a dual inter- and intra-organizational movement of rationalization through the development of new management techniques to respond to external pressures on companies to take social and environmental issues into account (for example, life-cycle models of social issue management) and internal efforts to reconcile these techniques with other managerial objectives (such as profit maximization). In this regard, current research on CSR/SD functions is, to a large extent, linking up with discussions from the late 1960s and early 1970s about the management of social issues (Ackerman 1975; Ackerman and Bauer 1976), revitalizing the stream of research usually referred to as being focused on “corporate social responsiveness” (Frederick 1978).

Although this initial approach to CSR/SD functions has largely vanished over time (Acquier, Daudigeos and Valiorgue 2011*), there has been renewed managerial interest in the concepts of CSR and SD. This first occurred in the late 1990s with the development of a “business case” for CSR/SD and was subsequently further advanced by ideas such as “markets for virtue” (Vogel 2005). The maintenance of corporate focus on CSR and/or SD continued despite the global financial crisis of 2007–08. This institutionalization of CSR/SD functions and the expansion of the role of dedicated CSR/SD professionals has created an upsurge in both academic and managerial interest in understanding the structuring of CSR/SD functions, the work performed by CSR/SD professionals within organizations, and the influence of CSR/SD functions and professionals on organizations’ ability to tackle CSR/SD-related challenges. Accordingly, focusing on the institutional dynamics underlying CSR/SD functions, the practice of CSR/SD professionals and their impact within and beyond their organizations is an ideal approach for a literature review that is based on a partnership between academics and practitioners (Sharma and Bansal 2020).

1.3. Scope and methodology of the review

Given the profusion of CSR/SD literature in recent years – Lu and Liu (2014) found more than 400 papers published annually between 2009 and 2014 in the Web of Science database alone – and the lack of studies specifically focused on the functional and professional aspects of CSR/SD, a relatively broad scope was adopted for this review. This made it possible to include studies from various subfields and to begin to consolidate the growing yet fragmented body of research on the role of CSR/SD functions and professionals.

Although this report seeks to follow a distinctive approach and takes into account both academic and managerial interests (Sharma and Bansal 2020), its focus on the emergence of CSR/SD functions and professionals does mean that there are areas of overlap with earlier literature reviews, such as those dealing with the literature on CSR/SD embedding and implementation (see, for example, Bertels, Papania and Papania 2010*; Maon, Lindgreen and Swaen 2010*) and reviews of individual-level studies of CSR, that is, of “micro-CSR research” (such as Gond et al. 2017*; Jones and Rupp 2018). The present review also overlaps with a few higher-level reviews of the entire CSR and SD research fields (such as Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Bansal and Song 2017). Table 2 presents the key takeaways and features of related reviews, indicating whether and how these overlap with the approach taken here.

Table 2. Related reviews: Areas of overlap and differences

|

Authors |

Focus and type of review* |

Key takeaways |

Areas of overlap with the present review and differences |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Maon, Lindgreen and Swaen (2010) |

CSR development and culture. Consolidative and integrative review. |

Integrative framework summarizing the key organizational stages and cultural phases of CSR implementation. |

Overlapping areas: Covers extensively the process of CSR implementation (see the section 2.1.2.3. on “Implementation and/or (de)coupling” in the present review). Differences: Because of its organizational focus, their review does not take into account the fact that implementing CSR usually involves CSR/SD functions and professionals. |

|

Bertels, Papania and Papania (2010) |

Embedding sustainability in organizational culture. SLR with the involvement of practitioners. |

Development of a framework showing all the practices required to embed sustainability (the “culture wheel”). |

Overlaps: Focus on “how-to” for individual professionals (competencies) and practice-based research. Differences: Intra-organizational focus means that the authors neglect, to some extent, the boundary processes that connect actors to their environment. |

|

Gond et al. (2017) |

Psychological micro-foundations of CSR. SLR. |

Behavioural framework covering the individual drivers of CSR engagement and employees’ perceptions of and reactions to CSR. Research agenda. |

Overlaps: Partial overlap in relation to how employees can become engaged in CSR. Differences: Does not consider how CSR/SD functions and professionals operate as an interface between employees and external stakeholders; does not take organizational dynamics into account. |

|

Jones and Rupp (2018) |

Psychological micro-foundations of CSR. Consolidative review. |

Notion that engagement in CSR is motivated by care-based, self-based and relationship-based concerns. Consolidative framework to explain employees’ reactions to CSR. |

Overlaps: Partial overlap in relation to how employees can become engaged in CSR. Differences: Focus on employees rather than CSR/SD professionals; organizational and extra-organizational dynamics are not taken into account in the analysis. |

|

Aguinis and Glavas (2012) |

CSR field as a whole. SLR. |

Integrative behavioural framework spanning micro, meso and macro levels. Research agenda focused on micro‑CSR and multilevel approaches. |

Overlaps: Similar willingness to embrace institutional, organizational and individual-level dynamics. Differences: Lack of studies of CSR/SD professionals at the time; lack of multilevel frameworks; no consideration of boundaries between an organization and its environment. |

|

Bansal and Song (2017) |

Corporate responsibility and corporate sustainability. SLR and historical genealogy. |

Account of the overlapping approaches of CSR and SD. Call for studies that differentiate between CSR and SD. |

Overlaps: Similar willingness to embrace institutional, organizational and individual-level dynamics. Differences: Differentiates between CSR and SD (in contrast to the present review’s approach); no specific interest in understanding the organizational structuring of CSR/SD functions. |

* CSR = Corporate social responsibility; SD = Sustainable Development; SLR = systematic literature review

A formal literature review process was adopted for this report, because defining boundaries and offering new categorizations can help to establish emerging fields of research (Gond, Mena and Mosonyi 2020) and to consolidate fragmented areas (Jones and Gatrell 2014; Mosonyi, Empson and Gond 2020). The key steps involved in the production of systematic literature reviews (see, for example, Denyer and Tranfield 2009; Rousseau, Manning and Denyer 2008) have generally been followed. The practical relevance and potential managerial impact of the review have been enhanced by working together with the ILO to better understand the review’s key parameters, as recommended by Bansal et al. (2012) and Sharma and Bansal (2020). This was complemented by interviews with a panel of academic experts working in the field of CSR/SD studies, which helped to make sense of the current challenges faced by researchers and to refine the report’s research agenda.

1.3.1. Defining the research context and formulating questions

In line with its Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work, published in 2019, and the blueprint contained therein for the promotion of a more human-centred world of work, the ILO called for a literature review focusing on the role played by CSR/SD functions and the impact of these functions within the workplace (that is, on employees), on the workplace (that is, on organizations’ business models) and through the workplace (that is, on external stakeholders). Once this context was defined, the authors of the present review engaged in discussions with ILO staff with a view to formulating a set of research questions that would address the ILO’s specific areas of interest. It was determined that the review should focus on whether and how CSR/SD functions and professionals can transform workplaces (and on the relevant political dynamics and considerations) and should strive to advance organizations’ knowledge of CSR/SD matters. Three topics were identified as being central to this literature review: Topic #1: Embedding CSR/SD functions and professionals; Topic #2: Managing stakeholder relations through CSR/SD boundary processes; and Topic #3: Shaping interactions with employees and trade unions through CSR/SD boundary processes.

1.3.2. Locating and selecting studies

the following key areas were identified: organization and management theory, CSR, governance studies, organizational behaviour and human resource management. The members of the research team discussed the temporal and disciplinary scope of the review with their ILO contacts. Timewise, it was decided to review articles published from 2000 onwards so as to better understand current thinking and findings. A list of prospective journals falling within the scope of the review was collectively drawn up and subsequently revised to include, notably, some journals from proximate disciplines in management (such as accounting) and in the social sciences (such as industrial relations, development studies and sociology), as well as some non-English‑language journals (from France). Reflecting the research team’s determination to combine rigour and relevance, the review covers practitioner-focused journals as well as academic journals.3

A similar set of keywords was used as a filter to identify all the relevant articles in the chosen journals. Slightly different keyword strategies were deployed to identify articles within generalist journals (such as Academy of Management Journal) on the one hand, and specialist journals (such as Journal of Business Ethics) on the other. The title, abstract and keywords of each prospective article were examined by one of the co-authors before a decision was taken on whether to include it in the review or not. The article’s relevance to one or more of the three core topics was rated on a three-point scale by the research team, with the review focusing on the most relevant articles (rated 2 or 3) for each topic.

1.3.3. Analysing, synthesizing and reporting

The next step was to identify the key characteristics of each article, including the type (empirical study, literature review and so on), methodological orientation (qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods), theoretical focus (for example, reliance on institutional theory) and various other elements that could help address the three core topics. As a result of this process, the level of analysis (individual, organizational, and institutional field) was also identified – a useful characteristic to record. The distinction made by Gond and Moser (2021) between different micro levels proved valuable in distinguishing CSR/SD functional dynamics from the work of CSR/SD professionals. However, a conceptual framework was required to make sense of the organizational and institutional dynamics that underlie CSR/SD functions and their institutionalization and to organize the review more effectively. The following subsection describes how a framework concentrating on “boundary processes” was developed to support the analysis.

1.3.4. Framing the review: An overarching framework of boundary processes

Central to the development of CSR/SD functions within organizations and the concomitant rise of new professional actors responsible for CSR/SD matters are dynamics that connect forces operating outside organizations (such as institutional, market and legal forces) to intra-organizational functional processes and to individual practices and reactions (Acquier 2016). Accordingly, the present review focuses on the environment–organization interface and relies on the notion of “organization as open polity” (Weber and Waeger 2017, 890), which emphasizes how the external and internal political environments of organizations are connected in ways that give rise to new occupational roles and organizational units and have the potential to transform organizational as well as environmental dynamics (Waeger and Weber 2019). The concept of a “boundary process” – defined as a process “through which an organizational polity interacts with and is thus coupled to its external environment” (Weber and Waeger 2017, 889) – is used to explore how an organization interacts with its political environment in ways that give rise to CSR/SD functions and that make these activities and the staff engaged in them potentially influential and impactful.

This concept is extended here to capture a broader variety of mechanisms whereby CSR/SD functions are shaped by and shape organizations’ capacity to deliver on the CSR/SD agenda. The ultimate impact of CSR/SD functions, policies and programmes on organizational outcomes and stakeholders’ welfare depends on boundary processes, where political forces from the environment interact with organizational and individual dynamics. By mapping these boundary processes, this report sought to identify the channels through which norms and standards, such as the ones developed by the ILO, influence whether and how CSR/SD functions can achieve their ultimate goals.

Figure 1 provides an overview of all the processes identified through the literature review. In Chapter 2 of the report, these processes are outlined and the main findings for each one presented. The tensions and debates emerging from the juxtaposition of all these studies are also discussed. Lastly, Chapter 3 provides a critical synthesis of the current state of knowledge.

Figure 1. Embedding CSR/SD functions and professionals: A boundary‑process framework

1.3.5. Developing a research agenda: Interviewing experts in the CSR/SD field

The research team interviewed a panel of six academic experts who have contributed to the literature on CSR/SD functions and professionals. These experts were selected on the basis of their publications, with each having published at least two articles in top-tier journals from among those identified during the review.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each expert, the average duration of the interviews being 54 minutes. The interview grid was designed to stimulate a conversation with purpose and broadly covered the three core topics mentioned in subsection 1.3.1. The questions were tailored to each interviewee’s publications in order to ensure that their specific expertise could be fully tapped. The main ideas arising from each interview were then synthetized with reference to the three core topics. This empirical material was used, together with the results of the review, to inform analysis of the current challenges in this research field and to develop the research agenda proposed in Chapter 3.

How CSR/SD functions emerge and interact with stakeholders: Reviewing the literature from the perspective of boundary processes

This part of the report describes the full range of boundary processes that were identified through the review. First of all, the findings on the boundary processes that underlie the embedding of CSR/SD functions and professionals within organizations are presented (section 2.1). The report then “zooms in” on how CSR/SD boundary processes shape organizations’ capacity to interact with their stakeholders (section 2.2) and on how these processes influence organizations’ interactions with employees and trade unions (section 2.3).

2.1. Embedding CSR/SD functions and professionals

The unprecedented adoption of CSR discourse and practice at the corporate level over the past 20 years has been accompanied by the emergence of new organizational functions devoted to the management of CSR/SD and of new professionals operating within these functions with dedicated occupational roles, such as “Chief Sustainability Officer”, “Climate Change Manager” or “CSR Manager”. In analysing these trends the research team was guided by three overarching questions:

-

How have CSR/SD functions been institutionalized and professionalized within organizations?

-

Who are the new CSR/SD professionals performing these functions?

-

How do professionals with CSR/SD functions operate?

The review undertaken for this report suggests that these trends have been the subject of highly disparate studies, which have relied on a variety of theoretical approaches (such as institutional theory and sense‑making theory) and have dealt with specific aspects of the embedding of CSR/SD functions (for example, the structuring of CSR/SD functions, or the impact of newly created occupational roles) and of the development of CSR/SD-related professional roles (for instance, the struggles faced by CSR/SD managers, or the competencies required to support the implementation of CSR/SD policies). Adapting the concept of a boundary process (see Figure 1), this report considers CSR/SD functions and professionals as boundary‑spanning entities that connect extra- and intra-organizational forces, and analyses how they may draw on or shift boundaries within organizations – for instance, between the departments dedicated to public relations, human resource management and communications – and between organizational actors. The boundary processes identified through the review are classified into three broad categories: (a) processes triggered at the macro level by an organization’s environment (such as regulation), which also include processes that play out at the environment–organization interface (such as professionalization); (b) processes involved in the structuring and deployment of CSR/SD functions (such as structuration and translation); and, lastly, (c) processes occurring at the level of individual CSR/SD professionals (such as institutional work and self-work). Table 3 provides definitions and illustrations of these three categories of boundary processes, which, in the following subsections, are presented in detail from the macro to the micro level of analysis.

Table 3. Boundary processes driving the emergence of CSR/SD functions and professionals

|

Boundary process |

Definition |

Key concepts and illustrative studies |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

Regulation |

Development of CSR/SD‑related (hard) regulations and (soft) norms, guidelines and standards that prompt organizations to introduce CSR/SD functions and recruit CSR/SD professionals. |

|

|

Commodification |

Creation of CSR/SD markets of consultancy products and services that make organizations susceptible to CSR/SD practices and tools and enable such practices and tools to achieve wide diffusion. |

|

|

Professionalization |

Emergence of CSR/SD professionals within and across organizations who share relatively similar aims, knowledge and practices and who form associations and/or communities of practice. |

|

|

|

||

|

Structuration |

Set of top-down, middle-ground and bottom-up processes that lead to the creation and positioning of formal CSR/SD functions within organizations. |

|

|

Translation |

Interpretive processes whereby external demands for CSR/SD are assimilated by an organization as actors there make sense of CSR/SD functions and activities. |

|

|

Implementation and decoupling |

Organizational and cultural processes whereby CSR/SD discourses are turned into actual policies and outcomes within organizations in ways that are more or less connected to external demands or pressures (from an organization’s institutional environment). |

|

|

|

||

|

Institutional work |

Purposive and practical actions of individuals within organizations that help to create, disrupt or maintain CSR/SD functions. |

|

|

Self-work |

Redefinition of CSR/SD professional roles and individual self to make sense of CSR/SD tensions and implement CSR/SD policies effectively. |

|

|

Competency-building |

Know-how, attitudes and competencies required of CSR/SD professionals so that they are able to perform their work. |

|

2.1.1. Macro-level boundary processes: Embedding of CSR/SD functions and professionals

The emergence of CSR/SD functions and professionals can be linked to “outside‑in” boundary processes, whereby the institutional and market environment of an organization leads to its adoption of a formal CSR/SD organizational structure. Three dynamics are of particular relevance in this respect: regulation, commodification and professionalization.

2.1.1.1. Regulation

Although CSR/SD has traditionally been defined by North American scholars as a set of voluntary corporate actions that go beyond legal requirements (Gatti et al. 2019*; McWilliams and Siegel 2001), several burgeoning streams of research have highlighted the growing and proactive role played by governments and supranational institutions (such as the European Union and the United Nations) in the CSR/SD space (Dentchev, Haezendonck and van Balen 2017*; Moon and Vogel 2008; Scherer, Palazzo and Matten 2014*), and also the blurring between the role of the State and that of corporations as a result of trends such as globalization (Scherer and Palazzo 2011*; Scherer, Palazzo and Matten 2014*). Gond, Kang and Moon (2011*), for instance, identified various configurations of corporate–government CSR/SD relationships along a spectrum ranging from both entities operating alongside each other, through partnerships and incentivizing, to corporations actually playing the role of a government (see also Albareda, Lozano and Ysa 2007*; Midttun et al. 2015*).

Concepts such as “corporate citizenship” (Matten and Crane 2005*) or “political CSR” (Scherer and Palazzo 2011*) have been coined precisely to capture the processes whereby private actors have taken over the role of governments, through their delivery of services traditionally offered by a government or through the participation of MNCs in deliberative democratic forums and emerging global governance platforms that seek to tackle social and/or environmental issues, such as human rights or global warming. Such a “retreat of the State” to the advantage of private actors suggests that the development of CSR/SD functions and professionals is related to macro-trends such as globalization (Scherer, Palazzo and Matten 2014*).

However, more recent studies of political CSR (Kourula et al. 2019*; Scherer et al. 2016*) have diagnosed a “return of the State” in the CSR realm, with governments playing the role of a strategic actor in the CSR/SD space that can intervene purposively and in various ways to mobilize and potentially capture private initiatives (Schrempf-Stirling 2018*), or even fully regulate them through a traditional command‑and‑control process. Schneider and Scherer (2019*) have clarified the multiple mechanisms underlying such governmental CSR interventions, which combine the design of incentives with the provision of expertise, knowledge and legitimacy to key actors in order to support the corporate adoption of CSR/SD. Particular attention has been paid to India, as its Government was one of the first – together with that of Mauritius in 2007 – to pass a law (the Companies Act 2013, Section 135) making it mandatory for companies to spend a certain amount of their profit on CSR/SD activities, in a move that radically calls into question the voluntary nature of CSR/SD (Gatti et al. 2019*). A subfield of study dedicated to “CSR and government” (Knudsen and Moon 2017) investigates the various mechanisms of governmental CSR intervention within and beyond national borders. Focusing on France, Giamporcaro, Gond and O’Sullivan (2020*) identify a series of hard, softer and indirect CSR/SD governmental interventions in the realm of responsible investment that have catalysed the growth of the asset management industry over the past 15 years. The regulation of CSR/SD information disclosure by corporations (New Economic Regulations Act), together with the creation of state-owned pension funds with a CSR/SD focus (Fonds de Réserve pour les Retraites, Établissement de Retraite Additionnelle de la Fonction Publique) and stronger regulation of institutional investors, has fostered the expansion of CSR/SD functions at asset management companies and in publicly held corporations in France.4

However, the CSR/SD regulatory sphere is far from being dominated solely by governments. A growing number of studies have analysed the role of private governance and non‑governmental standards as key drivers of CSR/SD adoption, even though their impact may be limited by their redundancies and overlapping nature. Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock (2011) have pointed to a proliferation of “international accountability standards” that constitute a new regulatory infrastructure for CSR/SD at the global level and encompass standards issued by organizations as diverse as the Global Reporting Initiative, the ILO or the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Researchers have investigated the complex regulative effects inherent in this multiplication of CSR/SD standards generally (Wijen 2014*) and in specific industries (Reinecke, Manning and von Hagen 2012*) and have studied the development and impact of standards such as ISO 26000 (Helms, Oliver and Webb 2012*). Although earlier discussions focused on whether these standards should be strict or loose, more recent studies have concentrated on how standards can enable CSR/SD professionals to act as voices of dissent within organizations, fostering “a culture devoted to (self)-reflection and discussion about basic assumptions, shared values, ideals and practices” (Christensen, Morsing and Thyssen 2013*) that can advance the achievement of CSR/SD objectives.

In general, there has been a continuous expansion of public and private regulations in the CSR/SD realm, which may be ascribed to trends such as globalization and pressures from civil society and investors and is driven by national governments and supranational institutions, as well as by private organizations and NGOs. This push for greater organizational accountability has fostered the development of dedicated CSR/SD functions in organizations and promoted CSR/SD professionalization by creating a common set of norms that make up the knowledge base of CSR/SD experts. Researchers have only just begun to explore how these multiple layers of regulation interact and shape the behaviour of organizations.

2.1.1.2. Commodification

Regulatory developments do not take place in a market vacuum: several studies have noted how a new professional category of CSR/SD consultants have acted as an “outside-in” pressure, leading to the embedding of CSR/SD functions in organizations. Such consultants have actively contributed to a process of “commodification” (Brès and Gond 2014*; Gond and Brès 2020*; Shamir 2005*), whereby social and environmental issues are turned into commodities and the size of the “market for virtue” is continuously expanded (Vogel 2005). There are several aspects to this process. First, by “furthering awareness and advancing CSR standards” (Molina 2008*, 31), consultants contribute to the boundary process of regulation, whereby hard and soft regulations are translated into CSR/SD concepts and practices for businesses, reducing the ambiguity inherent in such regulations (Edelman 1990; 1992). For example, Brès and Gond (2014*) show that “responsible purchasing” practices were diffused among leading corporations in Quebec through a forum designed by consultants to exchange best practices.5 Through commodification, consultants play an active role in enacting “responsive regulations” by mobilizing, promoting and translating CSR/SD regulations.

Second, earlier studies note how consultants have reshaped the meaning of CSR/SD discourses in ways that are directly compatible with business interests (Gond and Brès 2020*; Molina 2008*; Shamir 2005*), especially by advancing a “business case” rhetoric focused on the benefits of adopting CSR/SD (Skouloudis and Evangelinos 2014*). Shamir (2005*, 240), for instance, in his ethnographic study of how actors from “market-based NGOs” imported CSR into Israel, observed that consultants:

-

[…] typically invok[ed] a nonconfrontational rhetoric, typically abstain[ed] from highlighting potential tensions between profit-making imperatives and social commitments, and, on ground level, typically invoke[ed] a business-grounded rationale for the need to develop CSR.

However, other studies of CSR/SD consultants suggest that this focus on a business case rhetoric is only one of the many narratives that such consultants are juggling in order to make sense of their activities, as they must also balance the search for profit with more socially and environmentally meaningful practices (Ghadiri, Gond and Brès 2015*; Iatridis, Gond and Kesidou 2021*; Molina 2008*).6

Third, a recent study has shown how CSR/SD consultants construct the material infrastructure underlying the development of corporate CSR/SD functions and practices through their active role in designing and adapting management tools, such as life-cycle assessment methods, auditing tools or Deming’s inspired “Plan–Do–Check–Act” frameworks, to the specific needs of CSR/SD professionals (Gond and Brès 2020*). These tools are often a key resource for smaller CSR/SD functional units, which, without them, would not be able to devise or implement CSR/SD strategies. There is clearly an exchange of personnel and, hence, expertise between consultancies and CSR/SD units within organizations.

To sum up, the boundary process of commodification, which is largely driven by consultants, can augment, replace, anticipate and sidestep the influence of regulations. Consultants help to operationalize and rationalize new CSR/SD-focused business practices and tools that are then adopted by CSR/SD professionals; they may themselves also shape such regulations, which are usually aligned with their business interests (Brès and Gond 2014*). Through commodification, they continuously extend the reach of CSR/SD ideas, tools and practices to new organizations.

2.1.1.3. Professionalization

The emergence of CSR/SD consultants in the “market for virtue” reflects a more general boundary process in the institutional environment, namely the professionalization of CSR/SD activities and the endeavour to turn CSR/SD into a “profession” (Brès et al. 2019*). A profession can be loosely defined, following Abbott (1988), as an occupational group leveraging abstract expertise and proprietary techniques to establish exclusive control over an area of work (jurisdiction) within and across organizations. Professionalization involves translating these resources into social and economic rewards, thereby drawing (and redrawing) boundaries within organizations to create dedicated functional units, while establishing new professional organizations at the institutional field level. Institutional analysis has shown that the emergence of new occupational or professional groups within organizations is driven by regulation (Edelman 1990; 1992) and by the efforts made by social movements to normalize new organizational responsibilities (Augustine 2021*).

The professionalization of CSR/SD is indicative of the massive impact that corporate transition towards sustainability is expected to have on the workforce (ILO 2019b). It manifests itself not only in the emergence of in-house CSR/SD managers, dedicated CSR/SD consultants and environmental, social and governance analysts in financial markets, but also in the networking of nascent CSR/SD professionals that occurs through professional associations, which in turn foster the establishment of “communities of practice”. This networking usually involves CSR/SD professionals from various organizations within the same industry, but it may also occur across multiple industries and markets. Weller (2017*) looks at the emergence of CSR/SD professional associations in the United States – in particular the creation of Business for Social Responsibility in 1992 and the Corporate Responsibility Officer Association in 2005, which subsequently became the Corporate Responsibility Association – and discusses the competing role of ethics and compliance as a related professional domain (albeit one that is more concerned with the development of regulations). Associations of CSR/SD professionals have also mushroomed in Europe in recent years.7 Efforts have been made by industry associations to codify shared knowledge and establish standards. For example, the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, which was set up in 2005 and is focused on North America, has designed a voluntary sustainability standard that is currently used by sustainability professionals at over 1,000 colleges and universities to report on their work. Members of the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Management Education initiative, launched in 2007, sign up to six principles guiding management-related higher education. Moreover, professional associations such as the International Society of Sustainability Professionals and the Institute of Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability have developed certification programmes based on a set of qualifications that reflect a shared body of knowledge and expertise among those working in CSR/SD.

Weller (2017*; 2020*) has found that CSR/SD associations facilitate the formation of CSR/SD‑focused communities of practice, that is, “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger 2011, 1). This emphasis on shared passion is corroborated by Augustine (2021*), who found that sustainability managers saw themselves as part of a broader “movement for sustainability”. Such managers convene regularly through online forums and in-person conferences (Wright, Nyberg and Grant 2012*). Communities of practice operate within and across organizational boundaries and are characterized by the production and practical application of shared knowledge by their members (Brown and Duguid 1991), who may be said to possess a common identity as a group (Wenger 1998). CSR/SD‑focused communities of practice directly foster the development of CSR/SD functional units in organizations by equipping their members with a common knowledge, identity and purpose. In that sense they constitute a key boundary process connecting the CSR/SD activities of different organizations. Studies of the career paths of CSR/SD professionals indicate that most of them are driven by a quest for societal and ecological purpose across organizations. Other important factors are their alertness to changes in professional CSR/SD landscapes, which help them to orient their careers (Tams and Marshall 2011*), and their perception of the opportunity that such positions offer them to promote their take on “sustainability” (Koistinen et al. 2020*).

Current studies suggest that CSR/SD professionalization remains fragmented and that CSR/SD professions are regarded as still being in a nascent state (Brès et al. 2019*). For example, in the context of South Korea, Shin et al. (2021*) delineate four distinct and competing discourses of CSR professionalism held by CSR/SD practitioners that contribute both to legitimizing, and to fragmenting and undermining, the development of this institutional field. Furthermore, a recent dialogue between scholars from the CSR/SD field and scholars from the sociology of professions highlighted a number of peculiar features of CSR/SD professions, such as the lack of a clear knowledge base, relatively vague boundaries and recurrent questioning of the social and ecological impact of such work. It is debatable whether CSR/SD can ever become fully professionalized: indeed, it has been argued that CSR/SD could be a failed professional project, even though CSR/SD roles have become part of organizations’ structures (Brès et al. 2019*; Risi and Wickert 2017*). This conclusion was reached by Risi and Wickert (2017*) on the basis of 85 interviews with CSR/SD managers from German and Swiss corporations. They found that, over time, these managers were not able to advance their professionalization projects, but rather were marginalized to the organizational periphery. Accordingly, the institutionalization of CSR/SD functions and the professionalization of CSR/SD roles could follow diverging trajectories. Nevertheless, most scholars agree that CSR/SD roles have undergone, and are still undergoing, many of the typical processes involved in professionalization.

Although earlier research has highlighted the conceptual and empirical potential of focusing on CSR/SD professionalization, only a few studies have taken CSR/SD professions as the core unit of analysis. Moreover, knowledge of the many existing CSR/SD associations and communities of practice remains scarce. Future analysis could concentrate on the global–local tensions inherent in CSR/SD professionalization. Looking at settings such as “field-configuring events” (for instance, conferences or standard-setting discussions) and using tools such as network analysis could help to trace the development of various communities of CSR/SD professionals more accurately and to shed further light on how commodification and professionalization interact in the emergence of CSR/SD functions within organizations.

2.1.2. Meso-level boundary processes: Structuring CSR/SD functions

The institutional field-level boundary processes supporting the embedding of CSR/SD functions significantly overlap with the boundary processes at the organizational level that underlie the deployment of these functions. They include structuration, translation and sense‑making, and implementation and decoupling.

2.1.2.1. Structuration

Several loosely connected streams of research investigate the structuring of CSR/SD functions, following a top-down, middle-ground or bottom-up approach. The top-down approach is consistent with earlier analyses of corporate social responsiveness, which insisted on the need for executives to commit to the development of corporate capacities for dealing with social issues (Ackerman and Bauer 1976). Starting from the “upper echelons”, the first set of studies focused exclusively on the development of formal senior managerial positions related to CSR, exploring the various labels and job descriptions used to analyse what today are most commonly referred to as chief sustainability officer (CSO) positions (Strand 2013*; 2014*). This research has led to studies of senior management teams that usually rely on upper echelons theory – an approach that explores whether and how top managers influence their organizations (Hambrick and Mason 1984) – to determine whether and how CSR/SD positions or their holders’ beliefs and characteristics shape subsequent CSR/SD performance. Fu, Tang and Chen (2018*) found that the existence of a CSO position reduces subsequent “corporate social irresponsibility” more than it enhances CSR; Wiengarten, Lo and Lam (2017*) found the effect of having a CSO on corporate social performance to be significant and positive only when the position was filled by someone from inside the organization, the effect being stronger for female CSOs. The findings of Peters, Romi and Sanchez (2019*) are more nuanced, suggesting that the positive impact of a CSO on subsequent CSR-related performance is relatively long‑term (three years) and conditional on earlier CSR performance and on the chief executive officer’s (CEO) knowledge of sustainability. Kanashiro and Rivera (2019*) found the effect of a CSO position on subsequent corporate environmental performance to be stronger in industries with a high level of environmental regulation.

Other studies based on upper echelons theory have explored the influence of CEOs’ ideological orientations, belief in CSR/SD and personality traits on their organization’s CSR profile. For instance, drawing on their analysis of the ideological disposition of 249 CEOs, Chin, Hambrick and Trevino (2013*, 197) found that, in contrast to conservative CEOs, “liberal CEOs exhibit greater advances in CSR”, that “the influence of CEOs’ political liberalism on CSR is amplified when they have more power” and that “liberal CEOs’ CSR initiatives are less contingent on recent performance than are those of conservative CEOs”. Exploring CEOs’ beliefs and business ideologies, Hafenbrädl and Waeger (2017, 1601) came to the conclusion that:

-

[…] even though they believe in the business case for CSR, managers who hold a fair market ideology [that is, a tendency to justify and idealize the market economy system] will not readily engage in CSR because they experience weaker emotional reactions to ethical problems than managers who do not hold a fair market ideology.

On the whole, these results suggest that the organizational design of CSR/SD positions at senior management levels and CEOs’ beliefs may positively impact CSR/SD performance, at least when efforts are substantive rather than purely symbolic, such as in the recruitment of a CSO who is knowledgeable about CSR/SD and the corporate context, or the presence of senior executives who espouse progressive ideologies. However, the analysis by Mun and Jung (2018) of how gender diversity is promoted at Japanese companies suggests that top-level efforts to promote CSR/SD issues may not trickle down and may end up benefiting only the senior ranks of the organization.

The necessary, if not sufficient, motivation provided by senior management’s seal of approval when it comes to deploying and properly supporting CSR/SD functions is consistent with the findings of qualitative studies that have looked at how CSR/SD managers go about developing and expanding their prerogatives within organizations. For example, the study by Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian (2018*) of how CSR/SD was successfully embedded in a British energy company by a freshly appointed Head of CSR/SD highlights this manager’s continuous efforts to secure the support of key board members. The operational deployment of CSR/SD is usually left in the hands of middle managers who do not always have sufficient authority or discretion to implement CSR/SD strategies. Risi and Wickert (2017*, 622), for instance, found that only 10 per cent of the 85 German and Swiss CSR/SD managers whom they interviewed reported directly to the CEO, chairperson and/or the board of directors, and only a few of them had substantive or increasing budgets.

The lack of structural empowerment of CSR/SD managers has been noted recurrently, as has the struggle of such managers to create and/or protect their occupational jurisdictions (see, for example, Acquier 2016*; Augustine 2021*; Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian 2018*; Risi and Wickert 2017*). Studies of the interface between CSR/SD and other functions in an organization have identified coordination problems. In the case of the interface with accounting, the qualitative analysis by Egan and Tweedie (2018*, 1749) of the implementation of CSR/SD reporting at a large Australian corporation revealed that, “while accountants adapted well to early changes aligned to cost efficiency, they struggled to engage with more creative sustainability improvements”. Similar difficulties have been reported in earlier studies of how accountants can contribute to their organization’s CSR/SD agenda (Çalişkan 2014*) – an endeavour that may require specific “hybrid” competencies (Caron and Fortin 2014*). Gond, Igalens, Swaen and El Akremi (2011*) identified “territory battles” over ownership of employee-focused CSR/SD practices between the human resource and CSR/SD areas of a number of MNCs headquartered in France (see also Acosta, Acquier and Gond 2019*). Similar tensions between distinct categories of professionals have been identified for the related domains of ethics and compliance (see, for instance, Ben Khaled and Gond 2020; Chandler 2014). Acquier (2016*) highlighted the contrasting trajectories of CSR/SD functions at two different organizations: one an MNC from the sports industry that successfully embedded CSR/SD in its multiple subsidiaries across different regions; the other a European energy group in which the CSR/SD area became marginalized because of its focus on external reporting and its lack of capacity to inform strategy. Studies following a middle-ground approach indicate that, even when a CSR/SD unit has been established, it may struggle to expand its jurisdiction across the functional areas necessary for CSR/SD changes (Augustine 2021*) and so prove unable to influence other parts of the organization.

There has been less empirical research on the bottom-up boundary processes underlying the emergence and development of CSR/SR functions (Girschik, Svystunova and Lysova 2020), even though most studies focusing on middle management emphasize the importance of securing the support of employees for CSR/SD (Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian 2018*; Haugh and Talwar 2010*). However, in a very robust qualitative study conducted over 18 months at a large biomedical company in the United States, Soderstrom and Weber (2020*) identified bottom-up dynamics that explained why some sustainability concerns were assimilated by organizational structures while others were not. Central to such assimilation is the quality of interactions among the members of an organization; for example, when individuals put forward suggestions, they receive a response and are able to adjust the initial proposal accordingly (Weick 1979). Such interactions can trigger repeated cycles of exchanges, eventually leading to the formal structuring of an organization’s sustainability efforts. According to Soderstrom and Weber (2020*), successful interactions generated attention, motivation, knowledge, relationships and resources that could feed into emergent organizational structures.