COVID-19 Among Migrant Farmworkers in Canada: Employment Strain in a Transnational Context

Abstract

This study analyzes the conditions that migrant farmworkers in Canada endured prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic (January 2020-March 2022). It draws on policy analysis and open-ended interviews with workers in Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), as well as non-status migrants employed in agriculture. It evaluates policies and measures adopted by Canadian authorities to address labour shortages in agriculture and protect the health of migrant farmworkers. In recognizing the intersections of precarious employment and insecure residency status, the study advances an expanded employment strain approach to illustrate how longstanding immigration and labour laws, policies and practices, persisting alongside COVID-19 specific public policy interventions, aimed at improving the quality of and access to job resources for migrant farmworkers, serve to reinforce labour market insecurities confronted by this group of transnational workers. The report offers policy recommendations for improving working conditions, accommodations, and residency status.

Introduction1

The 2020-22 global COVID-19 pandemic reinforced inequalities between the global North and South, amplifying pre-existing disparties between migrant and citizen/permanent resident workers in receiving and sending states worldwide. Simultaneously, it revealed that many workers in occupations and sectors deemed “essential” enough to be exempt from stay-at-home orders and other public safety measures implemented in high-income receiving countries are in fact migrants. And those in Canadian agriculture present a case in point. Like many other OECD countries, the security of Canada’s local food supply rests on migrant workers. Consequently, alongside introducing sweeping public health and safety restrictions, during the global health pandemic the Canadian government sought to manage threats of national food shortages by boosting agricultural production and processing capacity in order to address an emerging backlog of produce and ensure that growers maintained access to migrant farmworkers. But while farms and greenhouses were declared essential worksites, justifying exemptions from border restrictions applicable to migrant farmworkers, they proved to be prone to COVID-19 outbreaks.

Drawing on policy analysis and open-ended interviews with workers enrolled in two streams of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) as well as non-status migrants employed in agriculture, this report explores these dynamics, highlighting the importance of migrant farmworkers to the Canadian economy, society, and the world of work alongside the conditions they endured during the pandemic (January 2020-March 2022) with the aim of advancing policy recommendations for improving working conditions, accommodations, and residency status.2 The report proceeds in six parts, beginning with an overview of research methods employed in this study in Part 1, including administrative data, policy and media analysis as well as qualitative interviews with thirty migrant farmworkers in Ontario and Quebec conducted between October 2021 and February 2022. Part 2 presents an overview of COVID-19 in Canada during the pandemic’s first four waves, considering rates, clusters, outbreaks and their drivers, and an examination of broad-based government responses to the pandemic, highlighting Canada’s partial border closures and efforts to activate domestic labour markets in essential industries. Shifting focus to agriculture, a major site of essential migrant work in Canada, Part 3 outlines the federal government’s approach to this sector during the pandemic, exploring admission policies applicable to migrant farmworkers and prevention of on-farm outbreaks, against the backdrop of provincial government policies and measures and practices adopted by regional health authorities to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in an industry long-defined by qualitative labour shortages—that is, characterized by conditions of work and employment undesirable to permanent resident and citizen workers—addressed principally through expansive guestworker programs. Part 4 presents findings that address workers’ experience of working and living conditions on the farms before the COVID-19 pandemic. Part 5 draws on our qualitative interviews to outline experiences of migrant farmworkers during the pandemic. Finally, Part 6 presents lessons learned and recommendations for improving the conditions of migrant farmworkers, including those voiced by the workers we interviewed. On the basis of this analysis, we argue that the migrant farmworkers' experience of their working and living conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic are strongly linked to those established on the farms prior to its emergence and, accordingly, to the terms, conditions, and organization of the migrant work programs in agriculture in which they are enrolled. At the same time, we demonstrate that the global health crisis deepened the structural vulnerabilities these workers experience.

Our analysis draws on insights from the “job strain” approach (e.g. Bakker and Demerouti 2006; Karasek 1979).3 We demonstrate that farmwork is associated with dirty, dangerous and difficult job demands (Bakker & Demerouti 2006), such as exposure to occupational hazards, pressure to maintain high levels of productivity, long weekly hours, and job insecurity. At the same time, we show that job resources (Bakker & Demerouti 2006; Karasek 1979), such as fair remuneration, job security and opportunities for promotion, which can serve as buffers against the impact of job demands on “job strain” (Karasek 1979; Karasek and Theorell 1990) available to farmworkers are deeply limited. Yet, we contend that while notions of “job demands,” “job resources,” and “job strain” advanced by the above-cited authors can be useful in apprehending and analyzing the employment experiences and needs of workers in agriculture, this framework assumes a citizen-worker holding a full-time continuous (i.e., permanent) job complete with a suite of entitlements and a often social wage – a standard employment relationship, so to speak (Vosko 2010). Consequently, the job demands/job strain model does not adequately capture the experiences of migrant farmworkers employed on fixed-term seasonal contracts and holding temporary or undocumented residency status. For this reason, we suggest that the notion of “employment strain” devised and advanced in scholarship on precarious employment, is of greater analytical value to our study. This “employment strain” perspective expands the job strain model to include employment relationships, such as temporary and contract-based employment, and employment relationship support, while attending to the effects of insecure residency status (see especially Lewchuk et al. 2006; Vosko 2006). In recognizing the intersections of precarious employment and insecure residency status, the engagement of an employment strain perspective herein thus seeks to address how longstanding immigration and labour laws, policies and practices, persisting alongside COVID-19 specific public policy interventions aimed at improving the quality of and access to job resources for migrant farmworkers, reinforce labour market insecurities confronted by this group of transnational workers. For instance, migrant farmworkers’ employer-specific work permits foster an ever- present threat of repatriation to one’s country of origin, otherwise known as ‘deportability’ (Basok, Bélanger & Rivas 2014; Vosko 2013 & 2019), heightening levels of employer control (Binford 2009) and impacting workers’ well-being in a multitude of ways.

Attention to employment relationships also points to ways in which employer control shapes workers’ experiences when they are not working. For instance, migrant farmworkers typically live in congregate and employer-provided housing well-documented to be seriously lacking in essential resources like hot running water, kitchen supplies and space, ventiliation, adequate toilets and showers, and laundry; such living conditions can inhibit well-being and, during a pandemic, intensify risks of transmitting COVID 19. Moreover, as non-citizens (both non-status and those holding temporary residency status) in Canada, strains, and workers’ responses to them, are produced through global inequalities in a transnational context, in which migrant workers in Canada are severed from their families and support networks that may serve as essential resources as well as a source of responsibility, often reflected by migrant farmworkers’ investment in their ability to send earnings home on a regular basis. In addressing these components of employment strain, the limits of job resources in buffering their effects are rendered more visible and complex.

Since for migrant farmworkers who reside on farms, the assumed separation between work and leisure is non-existent (Perry 2018; Horgan & Liinamaa 2017), strains associated with isolation, psychological hardships, and the poor living conditions unique to this workforce are vital components of employment strain, factors exacerbated by the conditions of prolonged forced confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, for migrant farmworkers, strain may also arise from prejudice and xenophobia on the part of the wider community. Viewed holistically, strains emanating from work, housing, community, and limited access to social and labour protections, amplified by the pandemic, undermine workers’ collective well-being.

Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-method and team-based methodology to explore the relationship between Canada’s TFWP, migrant farmworkers’ risks to COVID 19, and their experiences working and living in Canada during the pandemic. We combine a hypothetico-deductive approach to public policy with a holistic-inductive (Patton 2015) orientation to in-depth interviews with migrant farmworkers. The insights we offer flow from “active mixing” of critical public policy analysis with insights from migrant farmworkers, a recursive and dialogical strategy, that seeks to produce practical directives towards transformative change (Denzin 2010; Mirchandani et al. 2018). To interrogate public policy and centre worker’s experiences, we bring an employment relations lens to the jobs strains model because, we contend, this lens recognizes and reveals more effectively the structural conditions of the TFWP, the precariousness that characterizes migrant farmworkers’ work and residency status, and the interpretive field through which workers navigate, negotiate, and make sense of the options available to them.

In conducting our research, we relied on multiple methods: administrative data analysis; policy and media analysis drawn from the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020 through to March 2022; and semi-structured interviews of workers. Critical public policy analysis focused on federal and provincial laws and policies directed at migrant farmworkers issued principally in response to the COVID-19 crisis and submissions to and minutes of board meetings of local public health units. Informing our profile of Canada’s 2020 migrant workforce, illustrating trends in entry, source country concentration, and rates of COVID-19 transmission, statistical analysis of administrative data drew on customized data requests from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and publicly accessible data. In turn, media analysis entailed an extensive survey of Canadian-based reporting on policy development and on-farm outbreaks, revealing how the life and death implications of poor working conditions in agriculture reached a flashpoint in public discourse with a surge of media attention, particularly in the pandemic’s first and second waves, highlighting the insufficiency of policy interventions in producing meaningful protections for essential migrant farmworkers.

The qualitative component of the study employed purposeful sampling (Patton, 2015) to conduct semi-structured in-depth interviews with thirty migrant farmworkers enrolled in two streams of TFWP as well as non-status migrants employed in agriculture in Quebec and Ontario (Atkinson & Hammersley 1994; Tedlock 2000). Through this method, we were able to capture workers’ perceptions and experiences of their work and residency and explore the nature of the social phenomena under study, instead of setting out to test hypotheses about them (Atkinson and Hammersley 1994, 248). The guide that structured our interviews derives insight from the jobs-strain model as requested in the initial call for studies, but the interviewing strategy we undertook seeks to activate narratives that include the unique dimensions of migrant farmwork (such as employer-provided housing) that transcend the job-strain model. This open-ended approach to interviewing gave migrant farmworkers space to share the meanings and interpretations (Tedlock 200: 470) that they assign to their experiences as agricultural workers in Canada. Our research took place between October 2021 and February 2022 in Quebec and Ontario, Canada’s two most populous provinces and those in which a majority of migrant farmworkers in Canada are employed. In 2020, for instance, 50,126 temporary migrant farmworkers were employed in Canadian agriculture. That year, approximately 22,834 of such workers (or 45.6 per cent of all migrant farmworkers in Canada) worked in Ontario, while 13,094 (or 26 per cent of all migrant farmworkers in Canada) worked in Quebec (Hou, Picot, & Xu 2021). In the province of Quebec, we conducted the interviews in the Capitale-Nationale region and in the Montréal region. In the case of Ontario, we conducted all but one interview in the Leamington area and one interview in the Niagara region.

To recruit participants for this study, we relied on several strategies, including our previous contacts among migrant workers, as well as referrals by migrant support organization in Ontario and Quebec. In Quebec, RATTMAQ (Assistance Networks for Migrant Agricultural Workers in Quebec) played a vital part in our research. Not only did RATTMAQ put us in touch with many migrants, but a staff person from this organization emphasized to the workers the importance of our research project, thus encouraging them to share their stories with us. In addition, we also used snowball sampling to recruit other participants. We offered a small monetary compensation for the time migrant farmworkers spent answering our questions. The interviews were carried out in different places, for example in public spaces, in the homes of workers, on the premises of support organizations, and in the workplace. We also conducted some interviews remotely through the WhatsApp application. The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and subjected to primary and secondary analytic coding using a qualitative coding frame (Schrier 2014). The interviews were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006) a flexible, recursive strategy that lends itself to the dialogical and dynamic approach we take here. While we retain the themes generated from the interview guide, we foreground the way workers narrate their experiences of work and COVID-19 to problematize and render visible linkages, incongruities, perceptions, and silences between policies, practices, and the lived experiences of migrant farmworkers. All names utilized in this study are pseudonyms.

COVID-19 in Canada

2.1 Rates, Clusters, Outbreaks and their Drivers

As of 10 April 2022, when some Canadian provinces’ public health departments declared a sixth wave (on Ontario, see PHO 2022; on Quebec, see INSPQ 2022), Canada had faced five waves of COVID-19 outbreaks4 and reported a total of 3,568,337 cases of COVID-19 and 38,003 deaths resulting from complications related to the virus. Retrospectively, the magnitude of outbreaks varied regionally across the country, with Alberta and Saskatchewan seeing some of the highest rates of infection (pushing above 7,000 cumulative cases per 100,000 people by November 2021), and with the maritime provinces reporting around or below 1,000 cumulative cases per 100,000 people.5 Likewise, Canada’s provinces and territories have taken different approaches to curbing the spread of the virus. For example, in July 2020, the maritime provinces formed a travel bubble where residents of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island were free to travel between the three provinces, whereas residents of all other provinces and territories were required to self-isolate for 14 days upon arrival. Meanwhile, despite documenting the highest rise in case rates in North America in May 2021, Alberta was the first province to drop all COVID-19 related restrictions (in July 2021), ending mask mandates in public transit, taxis, and schools (Assaly 2021). Approaches to school closures also varied regionally; some provinces, such as Ontario, closed public schools and instituted online learning for months on end, whereas others, such as Quebec, facing similar outbreak levels, only instituted mandatory online learning for a few weeks at a time. As of 3 April 2022, the country’s full vaccination rate of those 5 years and older was 86 per cent, with some regional variation (for example, 85 per cent of those 5 years and older were fully vaccinated in Alberta compared to 90 per cent in Quebec).

Rates of infection also varied across industries and among workers, often on account of demands placed on those deemed “essential.” Unsurprisingly, those treating COVID-19 patients were rapidly impacted such that, in July 2020, at the tail end of Canada’s first wave, health care workers with COVID-19 accounted for 19.4 per cent of total cases (namely, 21,842 of 112, 672 total cases nationally). While the number of cases among health care workers grew throughout the pandemic, their share of cases fell as it continued: in June 2021, they accounted for 6.8 per cent of all cases (as of 15 June 2021, 94,873 healthcare workers had contracted COVID-19) (CIHI 2021). Beyond health care, worksite outbreaks occurred early in large meat-processing plants (April 2020), likely on account of the sector’s need for onsite work at specific times under conditions where physical distancing is often impossible. Such outbreaks included a large meat processing plant in High River, Alberta, where more than one-third of Canada’s beef is produced; in this case, more than 900 workers tested positive, and two workers died, among the 2,000 mostly new immigrants employed (Croteau 2020). Other meat processing plants in Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia experienced large-scale outbreaks and were forced to stop or slow production (Blaze Baum, Tait & Grant 2020). By December 2020, The Globe and Mail reported that infections spreading in manufacturing, including food manufacturing, warehouses, and construction worksites had surpassed cases in long-term residential care homes (the primary site of first-wave outbreaks in Canada) and accounted for 15 percent of continuing outbreaks in Ontario and 22 percent in Quebec (Marotta 2020). Oil-sands worksites in Alberta also proved to be particularly prone to extremely large outbreaks, at least two oil-sands worksites reported over 1,300 cases each in May 2021 (Yourex-West 2021), while Public Health Ontario reported that, as of 27 November 2021, farms and food processing plants had high numbers of workplace related transmission, reporting 3,238 and 3,995 cumulative cases, respectively (PHO 2021).

In its first four waves, the pandemic’s effects on workers were also racialized and gendered. Analysis of Statistic Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) data reveals that racialized workers, that is, persons, other than indigenous people, who identify themselves as non-Caucasian or non-White, are overrepresented in the industries accounting for 80 per cent of job losses during the initial waves of the pandemic, that is, between August 2020 and June 2021 (such as accommodation & food services, information, culture, and recreation, and wholesale & retail trade) (Alook et al. 2021). Meanwhile, LFS data also show that 56 per cent of racialized and white women workers employed between August 2020 and June 2021 worked in occupations with the highest risk of infection based on a Canadian adaptation of the O*Net index of physical proximity6 (high risk occupations include child care workers, personal support workers, cashiers, nurse practitioners, meat, poultry, and fish cutters and trimmers, among others), compared to 33 per cent of racialized men workers and 28 per cent of white men workers employed in this category of high risk jobs during this same time period (Alook et al. 2021).

Such variance across industries as well as among workers highlight the need to evaluate whether and the degree to which government policies aiming to secure labour supply for essential industries protected workers, including racialized migrant farm workers on temporary visas, from high rates of infection.

2.2 Canada’s Partial Border Closures and Efforts to Activate Domestic Labour Markets in Essential Industries

In early March 2020, the beginning of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, as daily cases began to rise, the government of Canada made overarching recommendations for work-from-home policies (10 March) and, eventually, usage of masks (7 April), published guidance on self-isolation (11 March), and began to issue travel restrictions. On 18 March, Canada closed its border to non-citizens for non-essential travel, and on 24 March, the federal government announced a mandatory 14-day self-isolation period for those returning from foreign travel. With respect to the travel ban, however, exemptions were made for international students and migrant farmworkers in an effort, as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) (2020b) proclaimed, “to safeguard the continuity of trade, commerce, health and food security for all.” Meanwhile, on 6 April 2020, the federal government launched the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), a $2,000 CAD monthly income support, for workers who lost income as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Complementing these efforts was a rapidly-implemented suite of government interventions to ensure labour force participation in essential industries. On 8 April 2020, in an effort to activate a growing portion of the domestic workforce experiencing unemployment related to social distancing requirements and mass layoffs in sectors such as food services and accommodations, the federal government expanded the Canada Summer Jobs Program, raising wage subsidies from 50 per cent to 100 per cent of the provincial minimum wage for public and private sector employers in need of workers to deliver essential services (PMO 2020). To further activate labour in essential services, immigration officials expedited hiring processes to move unemployed migrant workers, already present in Canada on closed work permit, threatened with a loss of residency status, into essential jobs, approving those who had secured jobs to start working even before a work permit was issued (IRCC 2020a). Additionally, on 23 April 2020, the federal government lifted the restriction limiting international students to a maximum of 20 hours of paid work per week, provided they were employed in an essential service or function, such as health care, critical infrastructure, or the supply of food (IRCC 2020b). Because international students were excluded from the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, which provided financial support to post-secondary students unable to find employment due to the pandemic, and travel to their country of origin was either impossible or very difficult, many international students were left with no other option but to work in essential and often front-line industries, including in agriculture, during the first and second wave.

Meanwhile, some jurisdictions implemented industry-specific measures to recruit workers into essential work; for example, starting 15 April 2020, Quebec implemented a $45-million program to recruit residents into farm work with a $100 weekly bonus (Government of Quebec 2020). Indeed, Canada’s early decision to keep borders open to migrant farmworkers, alongside efforts to activate local workers in essential industries and jobs, such as agriculture and farmwork (for example, harvesting) respectively, reflects the country’s deep reliance on this group for its local food supply.

2.3 Agriculture in Canada: An Essential Industry and Major Site of COVID-19 Outbreaks

In 2019, Canada issued 56,710 temporary work permits in agriculture under its Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). The possibility of temporary labour migration being interrupted by emergency public health measures in 2020, particularly international travel restrictions, thus posed potentially devastating consequences for growers dependent on migrant farmworkers who labour season-to-season in jobs undesirable to citizens or permanent residents. Under pressure from agricultural producers (Powell 2020; Grant 2020), the federal government lifted travel restrictions for agricultural workers and issued 52,040 temporary work permits in agriculture (a number comparable to previous years (IRCC 2022)). Unfortunately, these worksites proved to be prone to COVID-19 outbreaks. Although estimates vary by source, in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province and home to the majority of migrant farmworkers, alone, over 1,000 migrant farmworkers tested positive for COVID-19 between April and July 2020.7 Thus, while Ontario documented 36,594 cases by July 2020 (namely, 250 per 100,000) (Detsky & Bogoch 2020), the rate of infection among migrant farmworkers, 20,015 of whom entered Ontario during the spring and summer growing season, was approximately 4,996 cases per 100,000 people. Three workers from Mexico died from the virus in Ontario during 2020 raising questions prompting a death review panel by Ontario’s Deputy Chief Coroner on which one of the authors of this report served (Jhirad 2021). Bonifacio Eugenio-Romero, a 31-year-old migrant farmworker, died of COVID-19 complications in Windsor-Essex on 30 May 2020, following significant delays in receiving medical treatment. Twenty-four year-old Rogelio Muñoz died in an Essex County hospital in early June. And Juan Lopez Chaparro, a 55-year-old father of four, died on 18 June 2020 in a London, Ontario hospital after fighting COVID-19 for three weeks.8 While Public Health Ontario (2020) documented 49 outbreaks on farm worksites in 2020, the scale of outbreaks on individual Ontario farms was significant: data from Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board reveal that the farms with the largest outbreaks filed between 100 and 200 lost time claims related to COVID-19 in 2020 (WSIB 2021).9 Outbreaks on farms continued throughout the shoulder and into the 2021 season such that by 27 November 2021, Public Health Ontario (2021) documented 3,238 positive COVID-19 cases associated with 253 reported on-farm outbreaks (cumulative from April 2020). Moreover, between March and June 2021, five workers died during the mandatory quarantine period upon arrival in Ontario, at least one of which, Fausto Ramirez Plazas, from Mexico, from complications arising from COVID-19, which he contracted while quarantining upon arrival in Canada (Caxaj et al. 2022; MWAC 2021).10 Outbreaks likewise occurred on Quebec farms, although the Quebec INSPQ does not provide cumulative data of the order of its Ontario counterpart.11 High infection rates and mortality among migrant farmworkers are rooted in systemic gaps in protections and limited access to rights among migrant farmworkers before and during the pandemic; in other words, this lack of adequate protections and rights contribute to employment strains for migrant farmworkers. Before identifying these protection gaps and discussing their impact on employment strains among migrant farmworkers in Canada, however, we describe the temporary migration programs that enable Canada’s food industry to recruit and engage migrant labour. Next, we outline measures adopted by the federal government to secure labour for agricultural production while providing some income replacement supports for workers. We also review some provincial, and regional policies and practices to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 virus among agricultural workers, demonstrating that these measures resulted in limited resources to mitigate against the additional employment strains that the pandemic imposed on the migrant farm workers.

Migrant Farmworkers and Public Policy Interventions in Canada

3.1 Migrant Farmworkers’ Situation in Canada: The Nexus of Employment Strain and Insecure Residency Status

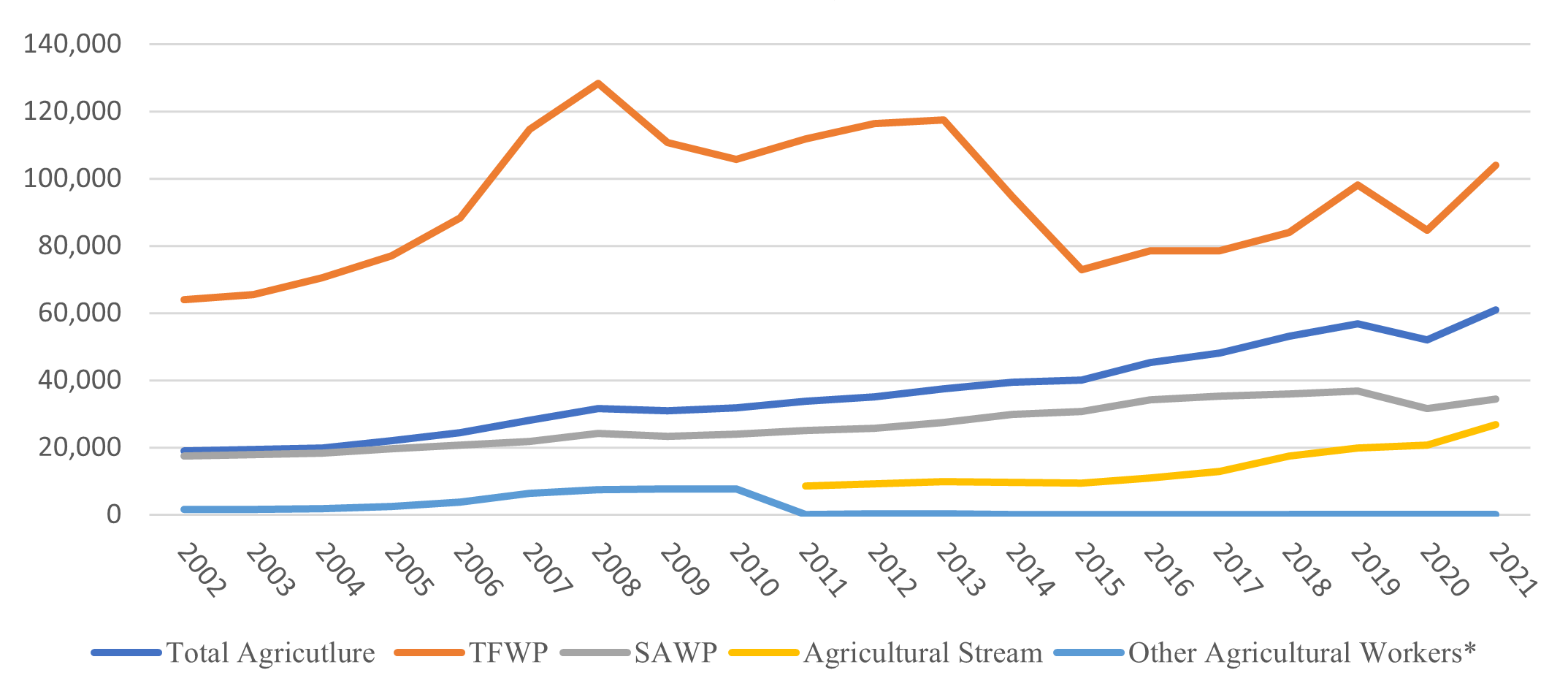

Migrant farmworkers in Canada include both legally-authorized migrants entering under temporary labour migration programs designed to manage migration, as well as migrants labouring without a valid work permit. While data on workers without legal status in Canadian agriculture is limited (Goldring & Landolt 2021), there are thousands of migrants working without work permits across the country; some estimates claim that up to 2,000 “undocumented” workers are located Ontario farming region Windsor-Essex alone (Gatehouse 2020). A majority of migrant farm workers in agriculture, are, however, legally-authorized and enter Canada principally through two subprograms of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) -- the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) and the Agricultural Stream. The TFWP allows Canadian employers, who claim that they cannot fill positions domestically, to hire migrant workers for temporary employment in Canada. With origins in bilateral agreements negotiated with specific states, the TFWP model is based on labour market tests, known contemporaneously as Labour Market Impact Assessments (LMIAs), questioned for the prioritization of meeting employer demands for labour over worker protection (Marsden, Tucker & Vosko 2021a), and justified on the basis of discourses of so-called labour scarcities or shortages (Sassen 1980; Sharma 2006; Hennebry & Preibisch 2012). LMIAs are used by Canada’s national labour ministries (namely, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and Service Canada), to evaluate whether hiring foreign nationals will negatively impact their labour markets. This determination is required for the issuance of a work permit by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). Although the TFWP was the predominant temporary migrant work program in Canada in the early-2000s, since the mid-2010s the number of TFWP work permit holders have declined on account principally of concerns related to worker protection, on the one hand, and protectionism on the other hand (Marsden, Tucker & Vosko 2021a)12. However, on account of the still significant employer demand, as Figure 1 shows, even though the TFWP as a whole contracted during this period, its most restrictive subprograms - the SAWP and the Agriculture Stream - grew slightly. Simultaneously, they came to represent a significant proportion of its TFWP; for instance, Agriculture Stream and SAWP participants accounted for 62 per cent of all TFWPs in 2020.

Figure 1 : Work Permit Holders in Canada by Year in which the Permits Became Effective, 2002-2021

Source: Vosko and Spring 2021 utilizing IRCC 2022 data.

*The “Other Agricultural Workers” stream includes high and low-wage agricultural workers working in production that is not included on the National Commodity List; the participation rate in this program has steadily declined since 2011 (when the Agricultural Stream was first introduced) and has sat at zero since 2018.

Canada’s largest and most longstanding program under the TFWP, the SAWP, has operated to meet agricultural employers’ need for low-wage, flexible labour on a seasonal basis without interruption since 1966. It enables circular migration and functions through agreements between the governments of Canada and Mexico and Canada and Caribbean states; as Table 1 shows, Mexico and Jamaica are the predominant source countries of origin for SAWP participants. Bilateral agreements set out the terms and conditions under which migrant farmworkers drawn from participating countries migrate to Canada temporarily.

Table 1: Work permit holders under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) of the TFWP, by Country of Citizenship (All 10 Participating Countries), 2011-2021*

|

Source Country |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mexico |

16,675 |

17,815 |

18,560 |

20,285 |

21,425 |

23,910 |

24,675 |

25,100 |

25,940 |

22,180 |

24,295 |

|

Jamaica |

6,655 |

6,370 |

7,150 |

7,705 |

7,730 |

8,580 |

8,745 |

9,050 |

9,175 |

8,020 |

8,830 |

|

Trinidad and Tobago, Republic of |

1,000 |

880 |

1,035 |

1,025 |

775 |

795 |

795 |

780 |

835 |

450 |

490 |

|

St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

190 |

170 |

210 |

210 |

225 |

240 |

285 |

285 |

320 |

310 |

245 |

|

St. Lucia |

140 |

145 |

180 |

200 |

230 |

210 |

270 |

185 |

150 |

170 |

130 |

|

Barbados |

185 |

175 |

140 |

165 |

170 |

175 |

165 |

180 |

165 |

120 |

100 |

|

Dominica |

110 |

100 |

130 |

115 |

110 |

125 |

130 |

105 |

125 |

100 |

105 |

|

Grenada |

65 |

45 |

65 |

60 |

45 |

65 |

90 |

120 |

110 |

110 |

60 |

|

St. Kitts-Nevis |

25 |

20 |

45 |

30 |

25 |

25 |

20 |

15 |

-- |

-- |

|

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

-- |

-- |

0 |

0 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

0 |

-- |

|

|

SAWP Total |

25,045 |

25,720 |

27,515 |

29,795 |

30,735 |

34,130 |

35,175 |

35,820 |

36,820 |

31,460 |

34,270 |

Source: IRCC 2022.

*"--" denotes values between 0 and 5, which are withheld by IRCC for privacy reasons.

Migrant farmworkers’ conditions of entry under the SAWP produce precarious migration statuses (Goldring & Landolt 2011). Temporary work permits provided under the SAWP allow for a maximum 8-month stay. They are also employer-tied, and permit growers to terminate and effectively repatriate workers prior to the expiration of their work permits if insufficient work is available or for other reasons (for example, illness or injury) (Satzewich 2007; Binford 2013; Basok, Bélanger & Rivas 2014; Vosko 2019). At the same time, the SAWP permits circularity or rotation; that is, SAWP participants that do not confront these obstacles are enabled to return year-after-year and many, including many in our sample, take part in the program longterm. Quite uniquely, unlike other many other international mobility and temporary migrant work programs, SAWP does not allow for spousal or family accompaniment, even though its recruitment policies prioritize workers with dependents (Rajkumar et al.2012); paradoxically, as some scholars have noted, this recruitment strategy works to ensure participants’’ annual return to countries of origin (McLaughlin, 2010; Wells et al., 2014; McLaughlin et al. 2017).

In addition to SAWP, Canadian growers may recruit migrant labour through the Agricultural Stream (AS). An outgrowth of The Pilot Project for Occupations Requiring Lower Levels of Formal Training (NOC C and D) (HRSDC 2011), which originated in 2002 and extended to agricultural workers in 2011,13 the younger (but rapidly growing) AS, like the SAWP, only encompasses primary agricultural work (namely, anything on the National Commodities List) (ESDC 2021a). Under the auspices of the AS, employers must also obtain a favourable LMIA to secure work permits. Unlike the SAWP, however, bilateral agreements between Canada and sending countries do not underpin the AS; consequently, the more highly de-regulated AS involves less mediation on the part of government, including in the recruitment of migrant labour and thus private recruiters play a central role. In this context, AS participants face unique challenges that can heighten precariousness; for example, private recruitment agencies may engage in questionable and illegal activities, including the sale of fake visas, charging workers’ recruitment fees, and the misrepresentation of jobs (see for e.g., Gesualdi-Fecteau et al. 2017; Gabriel & Macdonald 2018). The AS provides work permits for a maximum of 24 months (also with no option for spousal family accompaniment), and while participants may apply for a new permit if they wish to continue working in Canada and secure a job offer, circularity is not built into the design of the program as it is for a stay that does not exceed eight months. Despite this longer maximum duration of their stay (recall that the SAWP only allows for a max 8-month stay), work permits issued to migrant workers under the AS are, akin to the SAWP, tied to specific employers. Thus, while they reside in Canada, under both the SAWP and the AS, migrant farmworkers are not permitted to circulate freely in the labour force and even face constraints in transferring between agricultural employers (see for e.g., ESDC 2021b, XV 1-3); in this way, producing considerable “strains” beyond the job and even the employment relationship (for example, pertaining to residency status), conditions attached to work permits serve to undermine worker voice, and to inhibit any behaviour that might characterize migrant farmworkers as "trouble-makers" (Binford 2009).

Also, in contrast to the SAWP, the AS provides permits to workers from any country, and while Guatemala is the top source country for the AS, the participation of workers from Mexico, India, and Jamaica rose substantially in the late 2010s (see Table 2). In its first five years (2011-2015), annual numbers of AS permit-holders were relatively stable, ranging from a low of 8,490 to a high of 9,800. However, the numbers doubled between 2015 and 2019, reaching nearly 20,000 permit holders, over half of whom were citizens of Guatemala (see Table 2).

Table 2: Work permit holders under Agricultural Stream of the TFWP, by Country of Citizenship (Top 10 only), 2011-2021*

|

Source Country |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Guatemala |

4,430 |

4,805 |

5,255 |

5,370 |

5,645 |

6,465 |

8,115 |

9,575 |

11,470 |

11,945 |

14,975 |

|

Mexico |

390 |

705 |

655 |

445 |

495 |

875 |

995 |

1,755 |

2,030 |

3,180 |

4,645 |

|

India |

50 |

60 |

85 |

175 |

260 |

515 |

1,165 |

2,285 |

2,195 |

1,190 |

1,085 |

|

Philippines |

1,275 |

1,015 |

1,170 |

920 |

600 |

655 |

605 |

575 |

755 |

775 |

1,065 |

|

Thailand |

575 |

635 |

610 |

555 |

490 |

640 |

580 |

710 |

705 |

785 |

850 |

|

Jamaica |

275 |

335 |

375 |

370 |

250 |

285 |

170 |

620 |

575 |

720 |

840 |

|

Vietnam |

25 |

35 |

5 |

0 |

-- |

10 |

80 |

230 |

250 |

370 |

535 |

|

Honduras |

410 |

220 |

345 |

275 |

355 |

280 |

325 |

380 |

360 |

420 |

480 |

|

Nicaragua |

200 |

215 |

235 |

285 |

290 |

295 |

285 |

315 |

350 |

255 |

370 |

|

Ukraine |

65 |

205 |

240 |

280 |

205 |

185 |

110 |

170 |

175 |

165 |

265

|

|

Total Agricultural Stream |

8,490 |

9,120 |

9,800 |

9,565 |

9,305 |

10,915 |

12,875 |

17,310 |

19,890 |

20,710

|

26,730 |

Source: IRCC 2022.

* "--" Denotes values between 0 and 5, which are withheld by IRCC for privacy reasons.

3.2 Protection Gaps, Limited Access to Rights, and Employment Strain

While the TFWP is administered by federal departments and agencies, management of this program is complicated by the jurisdictional complexities of the Canadian federal system. For instance, though the federal government has primacy over immigration and negotiates MOUs and standard employment contracts with sending states, Canada’s provinces have the power to enact and enforce labour laws (except for workers falling in the federal jurisdiction) as well as policies applicable to (im)migrants. The provinces are also responsible for regulating and the provision of health insurance, while housing and public health measures are within the jurisdictional domain of municipalities. This patchwork of protection contributes to gaps in protections for and access to rights among migrant workers. Such gaps are heightened for migrant workers in agriculture in particular: although food production is a national priority, labour regulation falls within provincial jurisdiction and, in order to keep food costs low and farming competitive, many provinces either exempt or partially-exempt farmworkers (citizen and non-citizen alike) from legal protections (Preibisch 2007; Barnetson 2016; Vosko, Casey & Tucker 2019). For instance, Ontario and Alberta deny farmworkers access to statutory collective bargaining rights as well as minimum employment standards on the basis of “farm worker exceptionalism” (Tucker 2012; Vosko, Casey & Tucker 2019). Moreover, while agricultural workers, including those that are migrants, are technically covered by general (namely, not industry-specific) labour relations legislation in every other province in Canada, unionization among agricultural workers in Canada is rare,14 even among those seeking to exercise rights to organize and bargain collectively. Moreover, migrant workers face particular challenges as employer- and time-specific work permitholders (on the particular challenges faced by migrant farmworkers seeking to organize and collectively bargain in British Columbia, see Vosko 2018; Vosko 2019). In contrast, agricultural workers in Ontario are included in the Agricultural Employees Protection Act (AEPA), which technically protects agricultural workers’ right to form “employees’ associations” and requires that employers give employees’ association “reasonable opportunity” to make representations respecting the terms and conditions of employment (Agricultural Employees Protection Act 2002, s.5(1) and listen or read employees’ associations’ representations (Agricultural Employees Protection Act 2002, s. 5(6), but does not include a duty to bargain.15

Migrant farmworkers labouring without valid work permits, do not, on account of their “undocumented” status, have access to either public or private health insurance and are unable to seek recourse if employers violate labour laws or employment standards; in contrast, bilaterally-negotiated SAWP employment agreements provide migrant farmworkers with certain entitlements with respect to their weekly hours, periods of rest, and wages as well as the accommodations, meals, and health insurance (see ESDC 2021b; ESDC 2021c). The AS does not bind employers to terms established under the SAWP employment contract negotiated by sending and receiving governments; before submitting an LMIA under the AS, an employer must nevertheless complete and submit an employment contract (either using a sample employment contract provided by ESDC or another contract that covers the same items for inclusion). This contract must outline provisions on wages and deductions, housing, transportation costs, and must indicate the employer will respect provincial labour laws and employment standards consistent with regulations adopted under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002), starting in 2015 (ESDC 2021d; on changes emanating in 2015, see below; see also Marsden, Tucker & Vosko 2021b). For both SAWP and AS participants, however, these entitlements, or job resources, are limited or ill-enforced. For example, the SAWP requires employers to provide “clean, adequate living accommodations,” free of cost (with the exception of BC), and the template contract for the AS requires that housing be inspected and fulfil the provisions for the National Minimum Standards for Agricultural Accommodations; however, the housing provided is generally “dilapidated, unsanitary, overcrowded and poorly ventilated” (Preibisch & Hennebry 2011, 1035; see also Díaz Mendiburo & McLaughlin 2016; Perry 2018; Preibisch & Otero 2014). Findings of qualitative interviews undertaken for this study, presented in sections to follow align with scholarship documenting such conditions, despite requirements of the program. As discussed in Part 4, several migrants interviewed found their accommodations to be overcrowded, lacking required facilities and appliances, and unsanitary – living conditions that, on account of the blurred boundaries between home and workplace, are central to their experiences of employment strain.

In addition to poor housing conditions, farmwork is also characterized by high rates of work-related illness and injury linked to job demands such as long working hours without adequate periods of rest (see for e.g., Hennebry et al. 2012; McLaughlin 2009), exposure to pesticides (Basok 2002), and other dangerous working conditions that contribute high rates of injury on the job within in a “climate of coercion” (Caxaj & Cohen 2019); interviews conducted for this study give credence to these and other job demands that compromise farmworker health and well-being on a daily and long-term basis. In an apparent effort to address well-documented working conditions, the SAWP requires employers to ensure migrant farmworkers are registered for provincial/territorial health insurance, and the template employment contract for the AS indicates that employers are to arrange and pay for private health insurance upon arrival and until workers are eligible for provincial public health insurance. In Ontario, SAWP workers are entitled to provincial health insurance upon arrival (see Ontario Health Insurance Act, Recommendation 522, section 1.3(2)), while AS workers are eligible after a three-month waiting period. In other provinces, such as Quebec, where SAWP workers are not eligible for provincial health insurance immediately upon arrival, private health insurance must be acquired, though it can be paid for through deductions from wages (e.g., ESDC 2021b, V 2.c; VI 9). Private health insurance creates a range of barriers for migrant farmworkers insofar as some clinics do not provide direct billing to private insurers (Caxaj & Cohen 2020), compelling workers to pay out of pocket or neglect health concerns, and private insurers may refuse to cover certain health expenses. More broadly, despite legislative and contractual provisions around ensuring access to private and/or public health insurance, prevailing scholarship shows that workers often delay or neglect to seek the medical attention they require (Hennebry, McLaughlin, & Preibisch 2016). In combination, long working hours, lack of independent modes of transportation (Barnes 2013), limited knowledge of health insurance and/or coverage and how to access it, social isolation (Horgan & Liinamaa 2017), and fear of losing hours of paid work, termination, or medical repatriation (Orkin et al. 2014) create barriers to seeking health care. Here again, data gathered from interviews conducted for this study reinforce prevailing research findings. As some of the workers told us, their employers denied them access to health care. Furthermore, as discussed in Part 5, the fear of medical repatriation was a barrier to reporting COVID-19 symptoms and getting tested.

Job resources available to SAWP and AS participants, then, are circumscribed by: the limited number of workplace and housing inspections and their relative ineffectiveness (owing partly to the fact that farmworkers are excluded from key provisions of workplace laws (on the Ontario case, see Vosko, Tucker & Casey 2019); the application of a compliance model of enforcement of prevailing workplace laws and policies and provisions of standard employment agreements; and, their institutionalized deportability. With regards to receiving state government efforts to improve enforcement, for its part, in 2015, Canada introduced regulations to reduce exploitation and enforce workers' rights under the TFWP via amendments to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002). But despite their protective aims, these measures are limited insofar as they rely on provincial authorities to enforce workplace laws characterized by multiple full and partial exemptions (Marsden, Tucker & Vosko 2021b). As this report reveals, the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly at its height in 2020/21, revealed deficiencies of such protections offered by standard employment agreements and federal regulations. These shortcomings were, moreover, linked to the fact that such interventions sought to balance worker protections with employers’ interest in maintaining access to low-wage temporary labour force disempowered, in particular, by their institutionalized insecure residency or deportability (Vosko 2018). Characterized by the fear of being repatriated (DeGenova 2006) both immediately and from future migration for employment to Canada on account of the rotational character of the country’s primary program in agriculture (Vosko 2019), this institutionalized deportability circumscribes migrant farmworkers’ capacity to voice workplace grievances and/or to demand fair and safe working conditions, both individually and collectively (Basok 2002; Basok, Bélanger & Rivas 2014; Binford 2013; Vosko 2013 & 2019). As evidenced in the testimonies of study participants, it seriously compromises the effectiveness of existing “job resources”.

Moreover, longstanding and more recent efforts to better protect migrant farmworkers and bolster “job resources” are constrained by workers’ conditions of entry and insecurity of presence and their roots in countries have grown dependent on the exportation of labour (André 1990; Satzewich 1993 Chartrand & Vosko 2020). Similar to settler colonial states, such as Australia, New Zealand, and, increasingly, the United States, Canada grants migrant agricultural workers entry as economically necessary workers, available to work in jobs undesirable to citizen workers, but provides them with differential access to rights and entitlements available to citizens and permanent residents - including the ability to freely navigate the labour market without fear of repatriation, access to social supports like employment insurance in case of unemployment, and barrier-free access to publicly insured health care. In this context, migrant farmworkers habitually migrate to perform “essential” work (for example, preparation of fields, application of pesticides, fertilization, irrigation and harvesting, etc.), often at considerable risk to their own health and well-being (Vosko & Spring 2021). While sending states participating in the SAWP work with Canada to negotiate standard employment agreements outlining protections for participants and employ consular representatives in Canada to ensure participants’ access to such critical protections, consular officials’ role in addressing the poor living and working conditions to which migrant workers in agriculture are subject is inevitably complex given that one of the central motivations for these countries is to ensure that workers continue to participate in this program and support their household and communities by sending remittances. Additionally, because migrant farmworkers emigrate from contexts in which social well-being and economic security are circumvented by ongoing processes of land, resource, and labour expropriation, there is significant pressure on workers to join the global labour force (Chartrand &Vosko 2020). The possibility of sending remittances from a wealthier country home is thus both a contributor to employment strain, insofar as it can heighten dependency on the employer, but also a job resource. For most workers interviewed for the study, the vast disparity between economic conditions in their countries of origin (be they in Latin America or the Caribbean) was the main driver for participation in temporary migration programs to Canada.

3.3 Federal Interventions focused on Agriculture

Complementing successful efforts to ensure migrant farmworkers were available and physically present to work during the pandemic via selective border enforcement, Canada set out to introduce new protections and benefits - or so-called job resources - for migrant workers labouring under intensified job demands. In March 2020, ESDC outlined temporary guidelines to which employers of migrant workers were to adhere. One intervention was the decision to mandate and subsidize temporary income replacement during a 14-day quarantine period upon arrival. To support farmers, fish harvesters, and all food production and processing employers engaging migrant workers, the federal government announced that each employer was eligible to receive $1,500 per migrant farmworker subject to self-isolation upon arrival - a subsidy to be used to cover wages or costs of accommodations during this period (AAFC 2020). During their isolation period, employers of migrant farmworkers were to compensate employees for 30 hours a week, at the hourly rate of pay stipulated contractually (ESDC 2020a). The federal guidelines also indicated that employers could not authorize workers to work during the quarantine period, regardless of the nature of the work available (namely, tasks otherwise presumed to be acceptable during self-isolation, such as administrative tasks, were not to be performed). And, in 2021, the guidelines were updated to include a new provision barring employers from “deny[ing] assistance if the foreign worker requires the employer to assist with access to necessities of life” during the mandatory quarantine period (ESDC 2021).16 ESDC also issued guidance for employer-provided housing for migrant farmworkers, including the provision of separate housing for self-isolating and non-self-isolating workers and mandating that shared accommodations must allow for physical distancing, indicating, for example, that beds “must be at least two metres apart” and that common spaces must be cleaned and disinfected on a regular basis (ESDC 2020a, s. 11).

Yet, such interventions quickly proved insufficient in protecting migrant farmworkers during the pandemic. In terms of income support, while the mandatory and paid 14-day quarantine period upon arrival was a significant protective measure for migrant farmworkers, typically excluded from short- and long-term income supports, for workers who typically work a 50-60 hour week, compensation equivalent to 30 hours of work meant a significant loss of income and therefore remittances sent to support their families left behind, as the workers interviewed in our study acknowledged. Furthermore, not only did the government fail to provide income support for migrant farmworkers during mandated periods of return to countries of origin, it neglected to acknowledge many migrant farmworkers’ need for income supports during their seasonal employment contracts. Paradoxically, migrant farmworkers contribute to Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) system, and, as such, they are technically entitled to its suite of special benefits (namely, Sickness, Compassionate/Caregivers’ and Parental Benefits), but requirements for an ongoing work permit and social insurance number (SIN), together with qualifying requirements tied to duration of employment, frequently mean that they are ineligible for such benefits as well as for the regular EI benefits to which they contribute. Meanwhile, though migrant farmworkers were technically entitled to the Canadian Emergency Relief Benefit, prior income requirements and other eligibility criteria that assumed recipients to be citizens made the benefit inaccessible to some.

One situation, exemplifying the effects of such limitations, is found in the case of a group of SAWP workers from Trinidad and Tobago, who were stranded in Canada in December 2020 due to travel restrictions. Initially, on the basis of a qualifying requirement pegged to hours of work for a specified period, shown to make regular EI benefits inaccessible to many temporary and part-time workers, both those residing permanently in Canada and migrating to work therein (Vosko 2012), these workers were unable to access income support via EI; that is, despite being physically present in Canada after their contracts came to an end, their employer-specific work permits, which prevent migrant farmworkers from seeking employment elsewhere, made it impossible for them to be “ready and available for work” - a key requirement for eligibility for income replacement (Keung 2020).17 Climate disasters (both within Canada and sending states) during and beyond the pandemic, further illustrate the need for income support in the form of EI for migrant farmworkers whose work and/or travel might be interrupted. For instance, in 2021, flooding in the Sumas Prairie, an agricultural hub in British Columbia, resulted in the evacuation of flooded farms, prompting repatriation and/or unemployment for hundreds of migrant farmworkers without access to income supports (Xu 2021; Grochowski 2021).

Additionally, while ESDC’s guidance around accommodating social distancing and providing separate accommodations for infected workers is a potentially significant intervention considering employer-provided housing in Canadian agriculture is notoriously poor, it quickly became clear that such guidelines were insufficient. Despite ESDC’s requirements, the persistence of poor housing conditions came into public view early on during the pandemic. For instance, national news outlets reported on a video taken by a migrant farmworker on June 16, 2020 revealing living conditions in a Windsor-Essex bunkhouse that did not allow for physical distancing: bunkbeds separated by cardboard and bedsheets positioned only a few feet apart (CBC News 2020c; J4MW 2020);18 other workers, upon contracting COVID-19, described to the Globe and Mail “overcrowded living conditions, including small bedrooms with multiple sets of bunk beds” as well as “ill workers living with healthy ones, leaky toilets, and showers that only ran hot water” (Baum & Grant 2020a). Moreover, migrant farmworkers living in employer-provided accommodations reported being required by their employers to remain in crowded bunkhouses, with bicycle riding and grocery shopping prohibited (Mojtehedzadeh 2020; Hennebry et al. 2020). According to the workers interviewed in our study, employer-implemented restrictions on leaving the farm exacerbated their social isolation and feelings of entrapment, given especially that virtually no COVID-19 protections were put in place in their dwellings. Yet, as the Report of the Auditor General Report of Canada, published in December 2021, found ESDC’s 2020 inspections of farms employing migrant farmworkers found almost all employers compliant with the COVID-19 regulatory requirements governing housing (Office of the Auditor General of Canada 2021). The highly critical report of the Auditor General of Canada nevertheless shows that quarantine inspections had little or no evidence to support a determination of compliance and, where employers were documented to be in violation of these requirements, they were still deemed compliant (Office of the Auditor General of Canada 2021) -- an issue that only got worse in the 2021 season. Similarly, outbreak inspections were not conducted in a timely manner and, in a majority of cases, they did not contain evidence on whether or not employers provided sick or symptomatic workers with separate accommodations to self-isolate. These findings are consistent with past scholarly research, hitherto neglected at a policy level, that underscores shortcomings in the pre-pandemic compliance-based federal enforcement and inspection regime for temporary migrant workers, such as migrant farmworkers (Marsden, Tucker, Vosko 2021b; see also Tucker & Vosko 2021).

Throughout the pandemic, migrant farmworkers with closed work permits working and living under unjust and/or unsafe circumstances were eligible to apply for the Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers, a pre-pandemic federal program introduced in June 2019 that aims to provide open work permits to workers deemed to be “experiencing or at risk of abuse” (IRCC 2020c). In fact, one of the workers interviewed in our study, did apply for an open work permit under this program. However, despite the tenor of this policy response, the adjudication of applications is unclear, concerningly as a 2022 study conducted by Vancouver’s Migrant Workers Centre found that as of 31 July 2021, only 57.1 per cent of applications made under the program were granted (Aziz 2022). In reviewing immigration officers’ decisions on applications made under the program, the study found that officers applied a contracted definition of financial abuse and required significant evidence to support allegations of psychological abuse (Aziz 2022). The initiative also does not protect workers not currently in Canada, a limitation affecting migrant farmworkers participating in the SAWP and engaged in circular migration but also AS participants who are able to temporarily travel internationally during their up-to-two-year closed work visa. For instance, one migrant farmworker, interviewed in our study, was on vacation in Mexico and planning to return for his second year of a two-year contract under the AS, when he was fired. This worker felt he was unjustly terminated but was deemed ineligible for an open work permit since he had already returned to Mexico.

3.4 Provincial and Regional Policy Interventions focused on Agriculture

Given the complex jurisdictional framework in which regulation and protection of temporary migrant labour in agriculture takes place, provincial governments and regional health units also made efforts to better protect migrant farmworkers from the spread of COVID-19. For instance, in Ontario, the provincial labour department targeted high-risk workplaces, including farms, with COVID-19 related inspections. By December 2020, Ontario’s Ministry of Labour, Training, and Skills Development conducted 375 proactive and 95 reactive COVID-19 related inspections on farms and had issued 123 COVID-19 related orders to employers in agriculture (Government of Ontario 2021). Yet, despite these efforts, an inspection blitz in Southern Ontario agricultural hub Windsor-Essex in early 2021 still found 1 in 5 farms non-compliant with rules around social distancing and masking. As we learned from interviews with workers in Leamington, Ontario, on many farms social distancing or masking were not strictly enforced, and no additional measures (for example, provision of air filters) were adopted. Existing temporary wage-loss supports, including those provided by Quebec’s Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST) and Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB), were also available to migrant farmworkers at this time. As of December 2021, 2,796 lost-time claims related to COVID-19 in agriculture were allowed by WSIB since the beginning of the pandemic (WSIB 2021), and, while industry-specific data is not available in Quebec at the time of writing, in 2020 CNESST recognized across industry, 11,717 of 16,614 COVID-19 related claims (CNESST 2020). However, among the workers we interviewed only one received temporary wage-loss support via WSIB even though seven other workers were placed in quarantine due to COVID-19.

Adding to ESDC’s guidance, provinces also issued recommendations to employers in agriculture seeking to manage on-farm outbreaks. Ontario Ministry of Heath, for instance, recommended that employers limit or decrease congregate housing, organize workers into cohorts, screen workers for COVID-19 symptoms daily, facilitate physical distancing, among other suggestions (Ministry of Health 2020). In contrast, Quebec’s Public Health Branch of the Ministry of Health and Social Services issued much stronger recommendations and requirements, mandating that, for example, during mandatory quarantine periods upon arrival, temporary foreign workers be isolated in individual rooms with private bathrooms, be provided with means of communication and sources of entertainment (video games, radio, or television), as well as food, laundry services, and hygiene products (INSPQ 2021). The Public Health branch also recommended developing a post-quarantine housing plan that separates contagious and potentially contagious workers from each other as well as from other migrant farmworkers, and asked employers to avoid using dormitories with 3 or more beds and instead ensure workers are housed in single or double occupancy rooms (INSPQ 2021).

Given some of the shortcomings of federal and provincial guidance for employers of migrant farmworkers, some farming regions in Ontario also issued COVID-19 related guidelines targeting migrant farm workers. For instance, as co-authors explore in a previous publication in greater depth (Vosko & Spring 2021), at the beginning of the pandemic, the medical officer of health in Haldimand-Norfolk implemented requirements, through a Sect. 22 Order of the Health Protection and Promotion Act(1990), that no more than three workers could be housed together during mandatory self-isolation periods. However, although this requirement may have helped to protect workers isolating upon arrival, it failed to address the ongoing risks of living in bunkhouses during the pandemic. For instance, after leading an unsuccessful challenge to the Haldimand-Norfolk’s housing requirement (Schuyler Farms Limited v Nesathurai HSARB 2020; Schuyler Farms Limited v. Dr. Nesathurai ONSC, 2020), local employer Schuyler farms experienced an outbreak in November 2020 involving at least 13 migrant farmworkers (HNHU, 2020b). Other solutions to the risks and limitations of employer provided housing included the creation of a 125-room Isolation and Recovery Centre in Windsor, Ontario, operated by the Canadian Red Cross and funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC 2021a) - arguably a bandaid solution that, while providing space for migrant farmworkers to isolate and recover from COVID-19, did nothing to address the sorry state of employer provided housing in agriculture. Forms of xenophobic profiling and policing of visits to grocery stores and other amenities further tethered migrant farmworkers, who typically lack access to safe independent modes of transportation (see for e.g., Reid-Musson 2018), to their crowded bunkhouses during their time off by (Harley 2020); for instance, in May 2020, Haldimand-Norfolk County’s public health unit issued ID cards to TFWs indicating they have completed their 14-day isolation period (Craggs 2020). While short-lived, this ‘carding’ practice ostensibly encouraged local residents to interrogate TFWs and police their social inclusion and/or exclusion on the grounds of protecting the local community, despite the fact that many TFWs contracted COVID-19 after arriving in Canada (Hennebry et al. 2020). Migrant farmworkers interviewed for this study likewise describe the intensification of local residents’ hostilities that they experienced.

Meanwhile, in the wake of large outbreaks and two COVID-19 related deaths in Windsor-Essex county in June 2020, Leamington hospital Erie Shores Healthcare opened an assessment centre to test migrant farm workers (CBC News 2020a). It was expected that the workers would arrive on a bus to have their temperature checked and get swabbed for the virus. Yet, nine days later, only 750 of the expected 8,000 workers had been tested, and it was decided to close down the centre (CBC News 2020b). Also, in 2021, Windsor-Essex County Health Unit issued detailed requirements around physical distancing as well as the provision of personal protective equipment, cleaning products, and nutritious meals to ensure workers’ well-being during the mandatory self-isolation period; the section 22 order also detailed requirements to help limit the potential spread of COVID-19 on the worksite and in employer-provided housing after the mandatory isolation period (WECHU 2021). However, as discussed in Part 5, some of these regulations (for example, the provision of nutritious meals or physical distancing), were ignored on the farms where the workers we interviewed were employed.

As the foregoing discussion suggests, although some COVID-19 related public policy interventions aimed to increase job resources for migrant farmworkers, in light of pre-existing immigration and labour laws, policies and practices largely unaltered during the pandemic, long-established and new job resources actually diminished among this group. According to the employment strain model, a reduction in job resources in an occupation with high job demands is expected to contribute to greater strains on already strained workers. As illustrated above, there are limited employment resources, such as income support, available to migrant farmworkers to buffer these strains and, while those social benefits available via certain streams of the TFWP (such as access to healthcare services) have the potential to alleviate strain and support well-being, they are not readily accessible. Moreover, because migrant farmworkers are excluded from settlement services afforded to immigrant newcomers, including language training (Hennebry & Preibisch, 2012; Rajkumar et al., 2012; Roberts, 2020), there is no system of support enabling workers to access the care that their entitlement to health insurance implies. Supports needed for workers to access care in cases of workplace-injury, illness, and mental health (such as language translation, transportation, and healthcare access) are poorly funded, limited, ad hoc, uneven, and absent (Caxaj & Cohen, 2020; Caxaj et al., 2020; Colindres et al., 2021). For the most part, the protections provided via federal and provincial interventions to address COVID 19 reproduced these pre-existing gaps. Migrant farmworkers, as our findings show, thus negotiate these barriers through a complex set of expectations. The findings from our interviews, to which we now turn, further illustrate how workers’ experiences during COVD 19 were shaped by pre-existing working conditions, precarious status in Canada contingent upon compliance with job demands, and the transnational context in which they are situated, resulting in employment strains that available resources cannot buffer. Their accounts, presented in Part 4, foreground the ways in which workers negotiate and challenge these strains within a transnational space that transcends the presumed spatial configurations of the job strain model.

Pre-pandemic Employment Strains and their Impact on Migrant Farmworkers

4.1 Analyzing Interview Data through an Expanded Notion of Employment Strain

The employment strain framework we employ in this study draws on, yet departs from the notions of job strain, understood as a balance between job demands and job resources (Bakker & Demerouti 2006). Job demands, understood as “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (cognitive and emotional) effort or skills” are present in all occupations and as such they can be linked to certain physiological and psychological costs (Bakker & Demerouti 2006: 312). Examples of job demands include an unfavourable work environment, a requirement to work extended hours, high work pressure, and tense interactions with others, whether clients, co-workers, or supervisors. As we discuss below, these demands are well recognized by migrant farmworkers employed on farms in Ontario and Quebec. These job demands produce job strains, unless balanced by certain job resources, such as control over one’s work environment, participation in decision-making, fair renumeration, job security, opportunity for promotion, or co-worker support (Bakker & Demerouti 2006). For most farmworkers, such resources, linked narrowly to the workplace, are limited. As discussed below and in Part 3, migrant farm workers lack control over their working environment and do not contribute to decision-making. Their jobs are insecure and do not offer any possibilities of advancement. Furthermore, their wages are low by Canadian standards.

Although the job strain model elaborated by Bakker and Demerouti (2006) sheds light on the experiences of migrant farm workers, as indicated in Part 1, it has two limitations: first, it ignores employment relationships, and second, it understands job demands, resources and strains exclusively in national (rather than transnational).

With respect to the first criticism, the notion of job demands and job strains are of limited value in the context of precarious forms of employment, characterized by seasonality and a lack of permanency. By contrast, the notion of employment strain encompasses employment relationships, such as temporary and contract-based employment, employment support and household insecurity (see especially Lewchuk et al. 2005; Vosko 2005). In the case of migrant farmworkers, these employment relationships operate alongside insecure residency status. Utilizing the notion of “employment strain” alongside that of insecure or precarious residence status can thereby better attend to uncertainty over future job prospects, earnings, and location characteristic of precarious employment, such as employer-tied temporary employment among migrant farmworkers who either lack legal status in Canada or are admitted to Canada on employer-tied temporary work visas without opportunities to transition to permanent residency. This perspective draws attention to sharp disparities in power between employers and workers linked to the workers’ precarious legal status (Vosko 2005). The analysis presented below expands on the job strain perspective by including both transnational and employment relationships.

With respect to the second criticism, migrants live transnational lives, and therefore their experiences need to reflect transnational responsibilities and relationships. For instance, if renumeration is understood in transnational terms, which is including wage levels in source countries, and not just destination countries, Canadian-earned income can be seen as a valuable resource that, in many instances, makes job demands acceptable for the migrant farmworkers. Many of the workers interviewed acknowledge that the wide gap between what they can earn in their home countries and Canada is the reason they choose to come to work in Canada. This gap can be attributed to land, resource and labour expropriations in the workers’ countries of origin, as discussed in Part 3. The poverty and underemployment many workers face in their home countries propel them to seek jobs elsewhere, including Canada (Basok 2002; Binford 2013). The fact that migrant farmworkers improve their families’ standards of living through remittances (Basok 2003; Latapí 2012; Itzigsohn 1995) can thus be understood as the major psychic and material “resource” that, to a certain degree, provides a buffer against excessive job demands, albeit at the cost of long-term separation from their families and the impact this separation has on the migrants’ emotional and psychological health (Preibisch & Encalada Gretz 2013; McLaughlin et al. 2017). Furthermore, dependent on a continuous supply of remittances, migrant farmworkers often accept extreme subordination while in Canada. In other words, migrant farmworkers’ transnational belonging is both a “resource” that helps migrants to normalize superfluous job demands and a source of additional strain.

Also stemming from their transnational lives, most migrant farmworkers live in employer provided housing while in Canada, congregate housing that is typically located on the farms at which they work. This “physical compression of home and work into a singular geographic site” (Perry 2018) implies that their employment strain cannot be adequately understood without considering their living conditions. The strain characteristic of employer-provided housing may include overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and tensions in relations with other workers, as illustrated below. Tensions over resources that arise in the context of shared and overcrowded housing undermine workers’ solidarity and make it easier for employers to “segment and divide” their labour force (Perry 2018; Bélanger & Candiz 2015). Confinement to employer-provided housing during the COVID-19 pandemic intensified tensions with co-workers. It also deprived migrant farmworkers of an important job resource; namely, the ability to seek distraction from work and relieve some employment strain while engaging in religious, cultural, or social activities or sports and entertainment in nearby towns in the company of friends and relatives from the migrants’ hometowns or new friends made in Canada. Finally, for migrant farmworkers, admitted residing in Canada on a temporary basis, other sources of strain include their marginalization by the receiving community. All these strains, already present prior to the COVID-19 crisis, were amplified during the pandemic, impacting the well-being of some migrant farmworkers. Even though some adopted creative coping strategies, many of them still found that the working and living conditions they experienced during the pandemic further compromised their mental and physical health and well-being.

4.1.1 A Profile of Migrant Farmworker Participants