Realizing the opportunities of the platform economy through freedom of association and collective bargaining

Abstract

This study provides empirical evidence from different regions of the world to identify avenues for platform economy workers to access freedom of association and collective bargaining. It shows that collective protests, the establishment of new organizations of workers and platforms, social dialogue and, to a limited extent, collective bargaining are taking place in the platform economy. The experiences from the ground described in this study indicate ways and a demand to create an even more enabling environment for freedom of association and collective bargaining in order to realize the opportunities of the platform economy for workers and employers.

Introduction

The study’s focus: Freedom of association and collective bargaining in the platform economy

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated digital transformations that were already under way in the world of work. Therefore, realizing the opportunities of the platform economy for workers and businesses is currently on the political agenda of many ILO Member States.1

This study analyses access to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining in the emerging platform economy. The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work of 1998 states that as fundamental principles and rights at work, freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining are essential elements in “maintain[ing] the link between social progress and economic growth ... enabl[ing] the persons concerned, to claim freely and on the basis of equality of opportunity their fair share of the wealth which they have helped to generate, and to achieve fully their human potential”. The ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work of 2019 reaffirms that freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining are enabling rights and a key element for the attainment of inclusive and sustainable growth.2 The guarantee of these rights can help to ensure that the opportunities of the platform economy are realized for both employers and workers.

Freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining are fundamental principles and rights recognized in the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87) and the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98). These fundamental principles and rights apply to all employers and workers,3 with very limited and restricted exceptions.4

Box

-

Freedom of association: “Workers and employers, without distinction whatsoever, shall have the right to establish and, subject only to the rules of the organisation concerned, to join organisations of their own choosing without previous authorisation.” (Convention No. 87, Article 2)

-

Effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining: “Measures appropriate to national conditions shall be taken, where necessary, to encourage and promote the full development and utilisation of machinery for voluntary negotiation between employers or employers' organisations and workers' organisations, with a view to the regulation of terms and conditions of employment by means of collective agreements.” (Convention No. 98, Article 4)

Box

In line with two International Labour Conference resolutions,5 the revised plan of action on social dialogue and tripartism for the period 2019–23 to give effect to the conclusions adopted by the International Labour Conference in June 2018,6 which was approved by the Governing Body in 2019, and decisions by the Governing Body on the agenda of future sessions of the International Labour Conference,7 this study provides empirical evidence from different regions of the world to identify avenues for platform economy workers to access freedom of association and collective bargaining.

This study responds specifically to Appendix I, component 2(e) of the revised plan of action, which mandates the output to “continue research on access to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining of digital platform and gig economy workers”. The study also responds specifically to para. 13.a.v of the ILO’s Global call to action for a human-centred recovery from the COVID-19 crisis that is inclusive, sustainable and resilient, under which the ILO will strengthen its support of Member States’ efforts to “harness the fullest potential of technological progress and digitalization, including platform work, to create decent jobs and sustainable enterprises … including by reducing the digital divide between people and countries”. In addition, the study considers the guidance of the ILO Centenary Declaration, the Resolution concerning Inequalities and the World of Work 8 and the Conclusions of the Meeting of Experts on Non-Standard Forms of Employment.9

Diversity of the emerging platform economy

The exact size of the labour force in the platform economy is unknown as reliable data is still scarce (ILO 2022a). However, it is widely expected that the number of platform workers will rise in the coming years – potentially to about 90 million job opportunities in India alone (Augustinraj and Bajaj 2021).10

The number of digital labour platforms is rising and the emerging platform economy is transforming parts of the world of work

Work in the platform economy can take a multiplicity of forms. In general, digital labour platforms are classified into two broad categories: online web-based platforms and location-based platforms

Digital labour platforms offer benefits for workers and businesses and more broadly for consumers and society at large. For workers, digital labour platforms can create new income-generating and employment opportunities, while increasing their ability to combine their working hours with their daily lives. In particular, the platform economy can provide employment opportunities for groups of workers who are traditionally disadvantaged and face barriers in obtaining access to the labour market, including women, people with disabilities, young people, refugees, migrants, and workers with minority racial and ethnic backgrounds

In recent years, the growing popularity of the platform economy has increasingly been accompanied by coordinated group actions of platform workers including wildcat strikes, collective log-offs, and demonstrations in different parts of the world. Grievances are mainly related to pay, working conditions, employment classification and occupational safety and health (Bessa et al. 2022).

While the platform economy creates income-generating opportunities by facilitating access to labour markets for workers around the world, there are warnings that access to decent work may sometimes be difficult. Among others, this may relate to challenges in the exercise of fundamental principles and rights at work, an insufficient amount of work to sustain a living, inadequate social protection, low remuneration, long working hours, occupational health and safety issues, discriminatory practices, unfair termination, lack of access to dispute settlement mechanisms and skills underutilization (ILO 2022a; ILO 2021a; ILO 2021d; Wood et al. 2019; Berg et al. 2018).

In the G20 countries, “about 90% of the respondents on taxi and delivery platforms reported that work through platforms was their main source of income and these proportions were quite similar across countries” (ILO 2021a).

The large variety of opportunities and challenges also relates to the diverging characteristics, capabilities and needs of the workers active in the platform economy (ILO 2022a; ILO 2021a). A significant difference is the question whether a worker uses the platform economy as a permanent main source of income or as a supplementary income for a limited period

Access to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining

Workers and employers have the right to establish and join organizations of their choice in order to promote and defend their respective interests, as well as the right to negotiate collectively with the other party. Many regulations in the labour market are based, among other things, on the assumption of the existence of an imbalance of bargaining power between individuals and their employers when negotiating pay and conditions of work (Freedland and Davies 1983). The rationale behind collective bargaining is to counter the lack of individual bargaining power and strengthen the unequal and therefore vulnerable position of an individual supplier of labour vis-à-vis the employer. The right to freedom of association is a precondition for collective bargaining to flourish.

During the emergence of the platform economy, there have been widespread assumptions that legal and practical difficulties would make it almost impossible for platform workers to participate in organizations of workers, coordinated group actions (such as protests, demonstrations or collectively logging out of the app) and collective bargaining

Practical and legal challenges related to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining in the platform economy

The practical obstacles to organizing and bargaining collectively on behalf of workers in the platform economy that are cited in the lliterature include the geographic dispersion of these workers in disconnected workplace locations such as their own vehicles or their own or customers’ private homes; the difficulties this creates for generating collective consciousness, compounded by the platforms’ encouragement of an individualistic, entrepreneurial image of platform work; the frequent turnover among workers; and the prospect of retribution against those who attempt to unionize without effective protections (Rodríguez Fernández 2020;

Most relevant international labour standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining:

The legal challenges often relate to an incorrect classification of platform workers as self-employed or independent contractors

At the ILO, the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) (2020) recalled that “the full range of fundamental principles and rights at work are applicable to platform workers in the same way as to all other workers, irrespective of their employment classification”.14

Box

-

In 2019, in a direct request relating specifically to the platform economy the CEACR invited a Government “to hold consultations with the parties concerned with a view to ensuring that all platform workers covered by the Convention [No. 98], irrespective of their contractual status, are authorized to participate in free and voluntary collective bargaining. Considering that such consultations are intended to enable the Government and the social partners concerned to identify the appropriate adjustments to make to the collective bargaining mechanisms to facilitate their application to the various categories of platform workers, the Committee requests the Government to provide information on any progress achieved in this regard.”16

-

In 2017, the CEACR recalled that Article 4 of Convention No. 98 “establishes the principle of free and voluntary collective bargaining and the autonomy of the bargaining parties with respect to all workers and employers covered by the Convention. As regards the self-employed, the Committee [recalled], in its 2012 General Survey on the fundamental Conventions, paragraph 209, that the right to collective bargaining should also cover organizations representing self-employed workers”.17

-

In 2016, the CAS had a diverse and rich discussion on the collective bargaining rights of self-employed workers in the context of a case concerning Ireland under Convention No. 98. In its consensual conclusion, reflecting on the divergent views held by the ILO constituents, the “Committee noted that this case related to issues of EU and Irish competition law … [and] suggested that the Government and the social partners identify the types of contractual arrangements that would have a bearing on collective bargaining mechanisms”.18

-

In two cases, the CFA requested the Governments concerned “to hold consultations … with all the parties involved with the aim of finding a mutually acceptable solution so as to ensure that workers who are self-employed could fully enjoy trade union rights for the purpose of furthering and defending their interest, including by the means of collective bargaining; and … in consultation with the social partners concerned, to identify the particularities of self-employed workers that have a bearing on collective bargaining so as to develop specific collective bargaining mechanisms relevant to self-employed workers, if appropriate”.19

Research approach and main findings

This study provides empirical evidence from different regions of the world to identify avenues for platform economy workers to access freedom of association and collective bargaining. It shows that collective protests, the establishment of new organizations of workers and platforms, social dialogue and (to a limited extent) collective bargaining are taking place in the platform economy. The experiences from the ground described in this study indicate ways and a demand to create an even more enabling environment for freedom of association and collective bargaining in order to realize the opportunities of the platform economy for employers and workers.

In the preparatory phase of this research project, initial interviews with about 15 experts, such as representatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations and experts from academia, were conducted to identify important developments and potential case studies in different regions of the world (initial interviews were conducted between February and April 2021). It is important to note that the case studies in this working paper are limited to describing developments regarding access to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; they do not analyse in depth the working conditions of platform workers.

Chapter 1 provides a quantitative analysis of country surveys that were conducted among app-based and traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers. The surveys were conducted in Argentina, Chile, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco and Ukraine, with a total of 6,739 respondents who were app-based or traditional taxi drivers or delivery workers. This chapter shows the motivation of location-based platform workers to engage with each other and join different types of groups for the exchange of experience on issues of common interest or to collectively improve their working conditions. Most of the surveyed app-based delivery workers and taxi drivers were not aware of a trade union organization of which they could become a member. Instead, they mostly organized in informal groups of workers, for example on Facebook or WhatsApp or in other social media groups.

Chapter 2 calls attention to the situation “on the ground” by documenting concrete examples of organizing and bargaining collectively in the platform economy. Case studies were commissioned in Australia, Chile, India, Nigeria, Ukraine and Spain. The case studies were developed by local experts, who conducted about 20 interviews with national informants (ranging from workers and representatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations to academic researchers). The country examples describe efforts by employers’ and workers’ organizations to reach out to workers on digital labour platforms and how these workers self-organize with a view to influencing their terms and conditions of work. It also shows the potential contributions that social dialogue and collective bargaining can make to resolving labour conflicts in the platform economy.

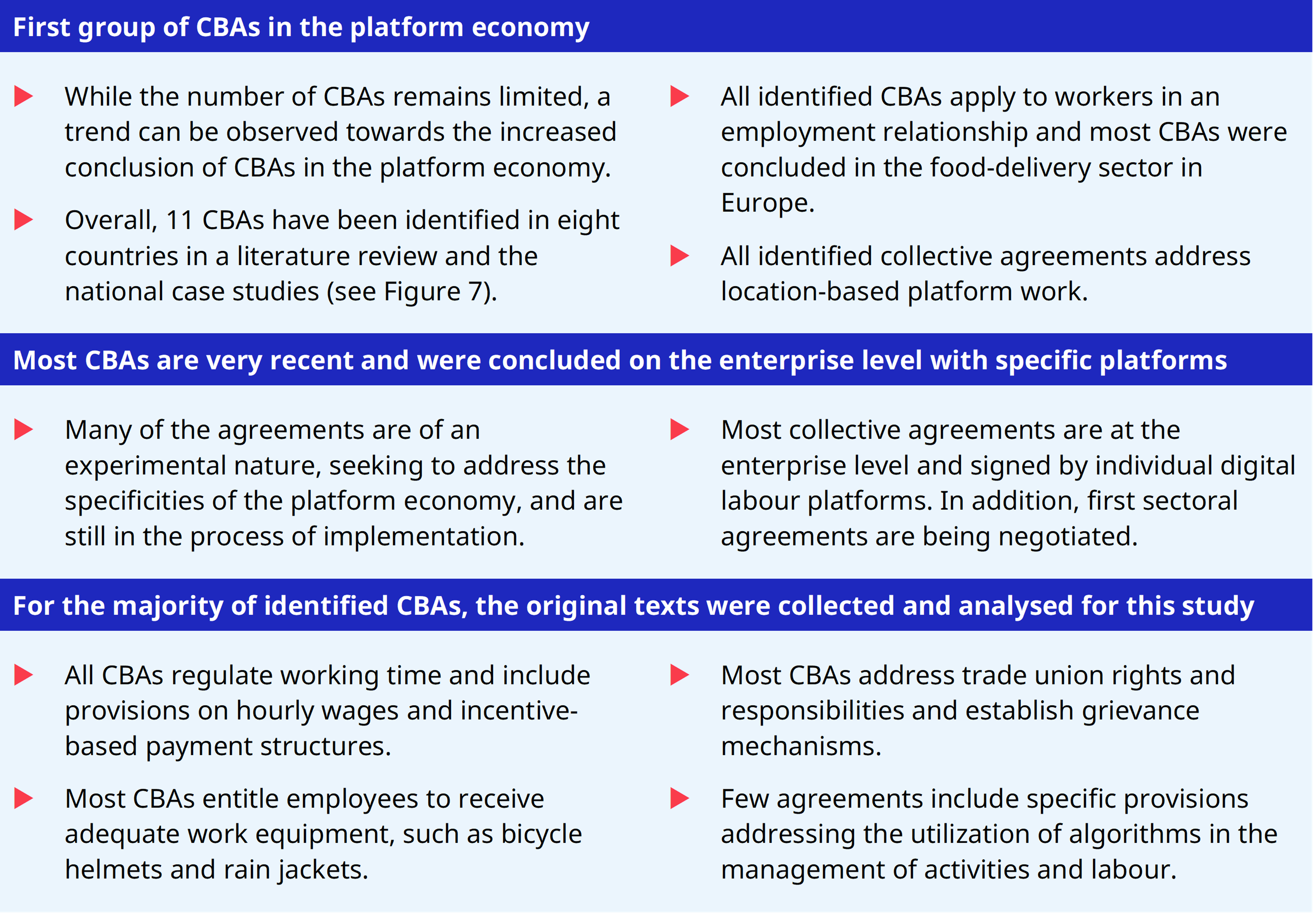

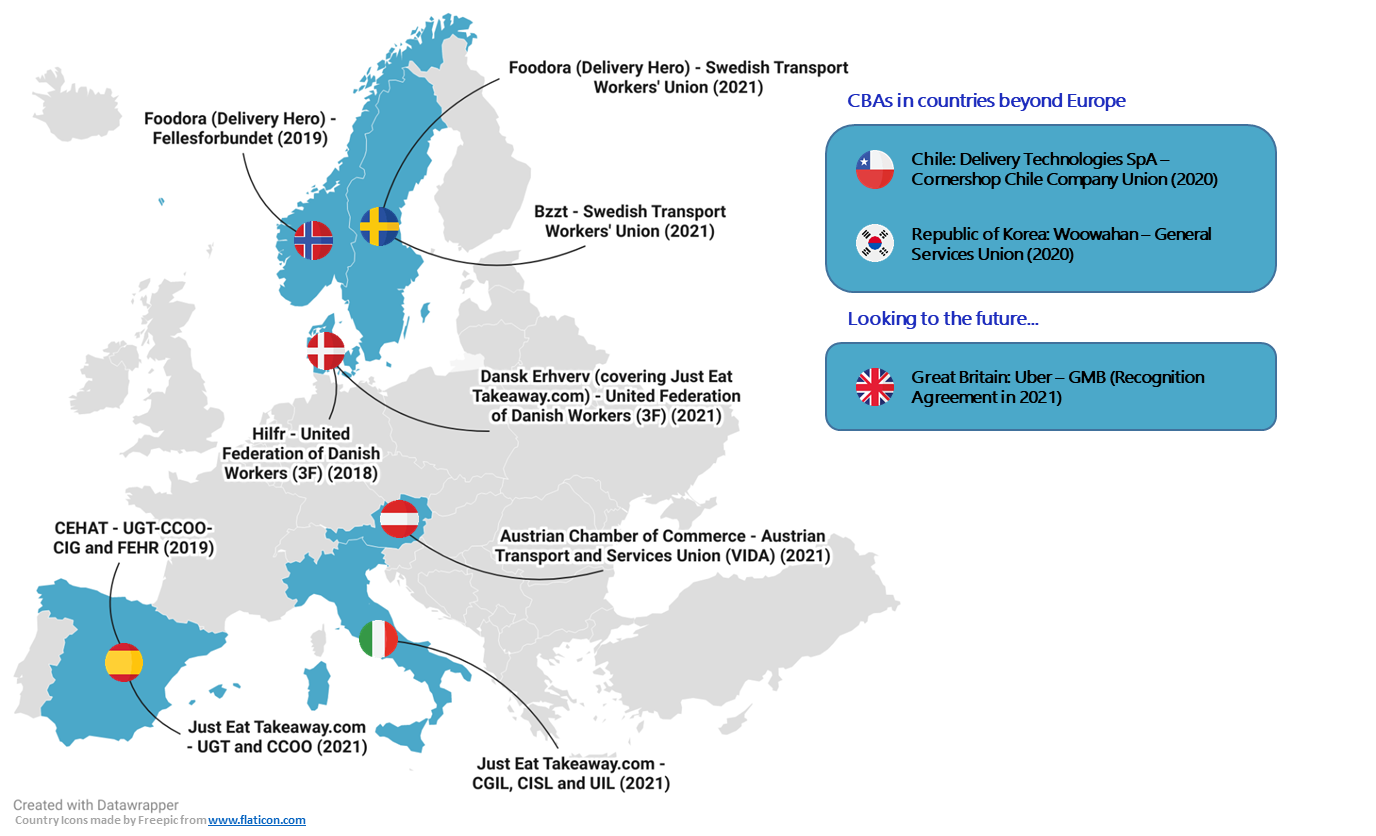

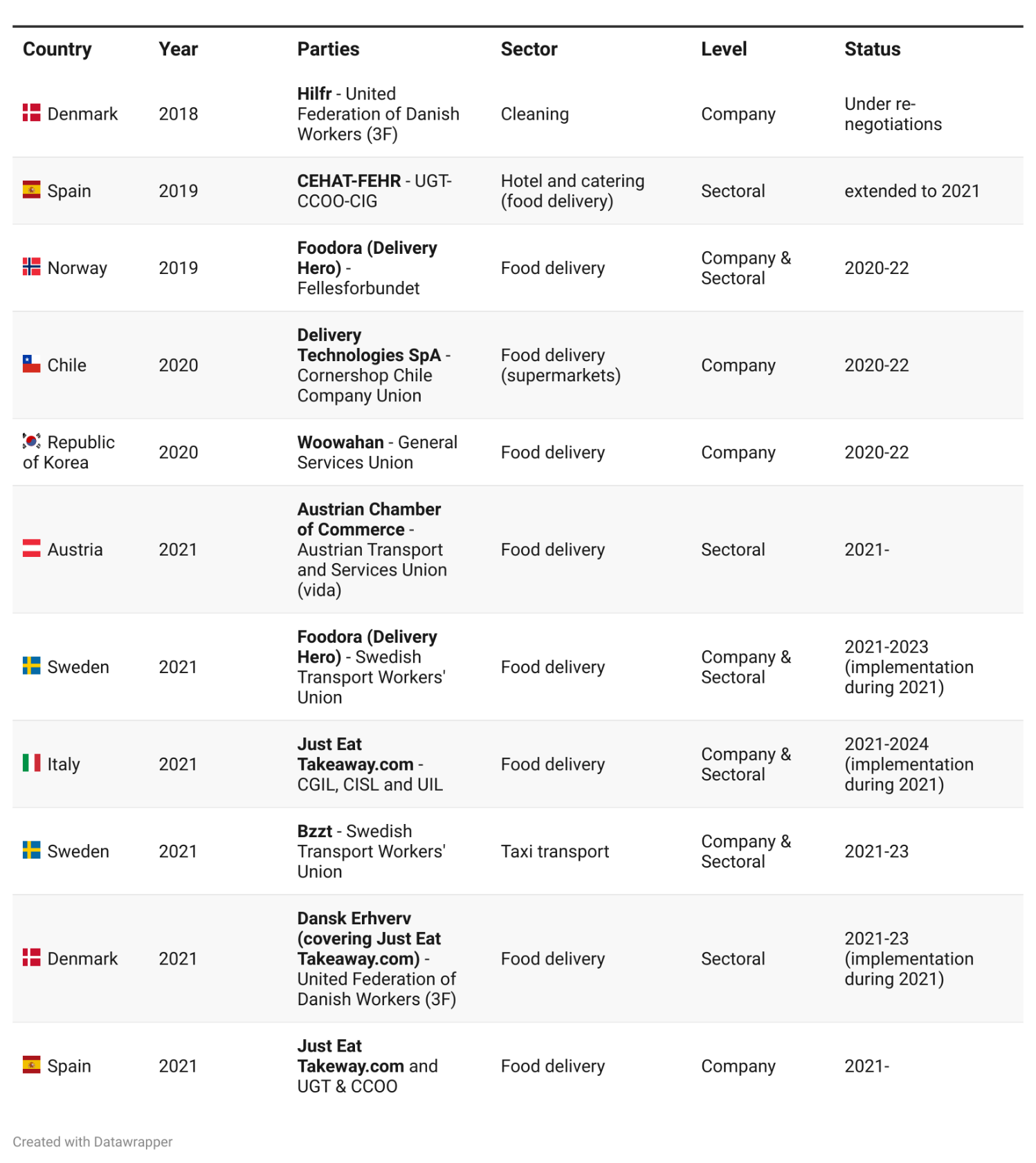

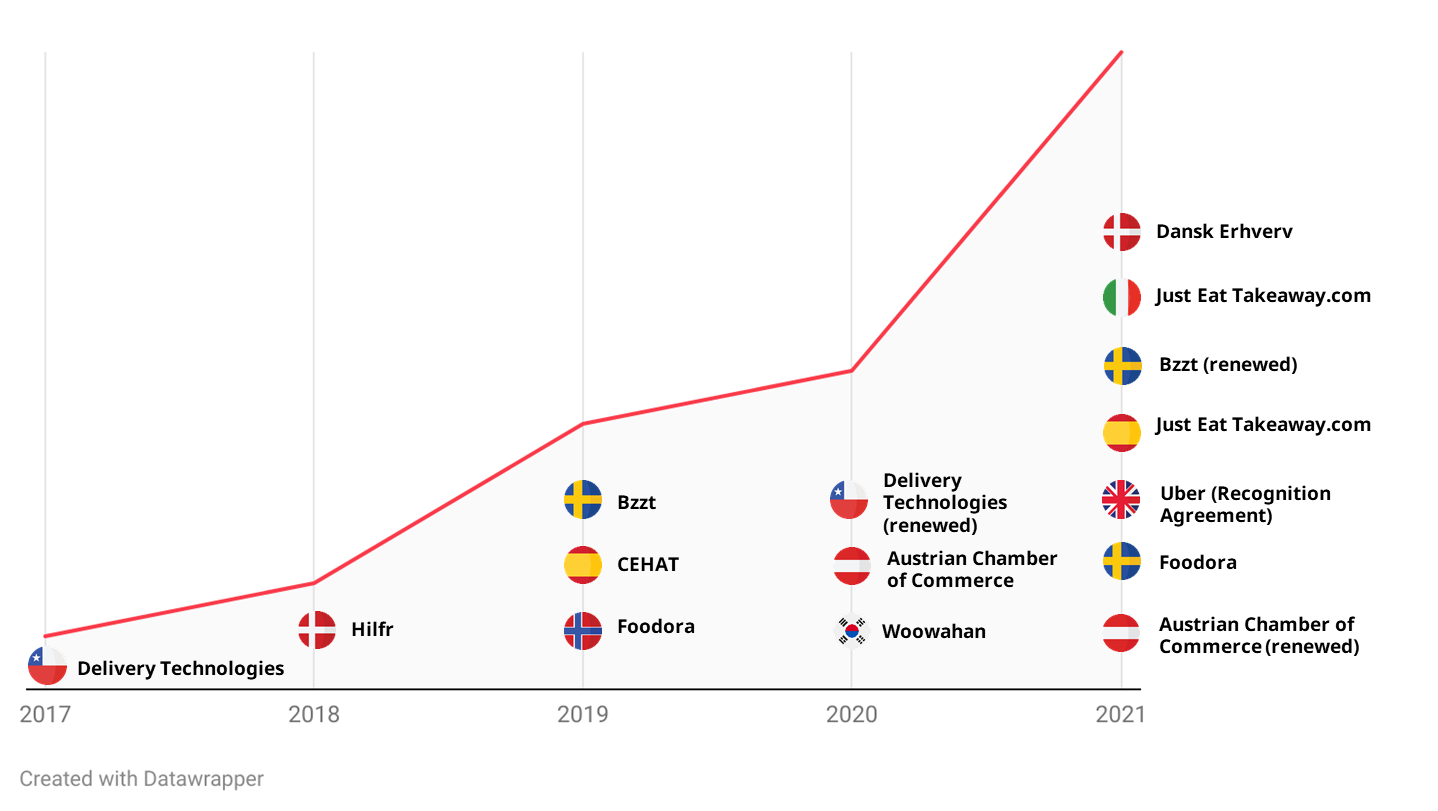

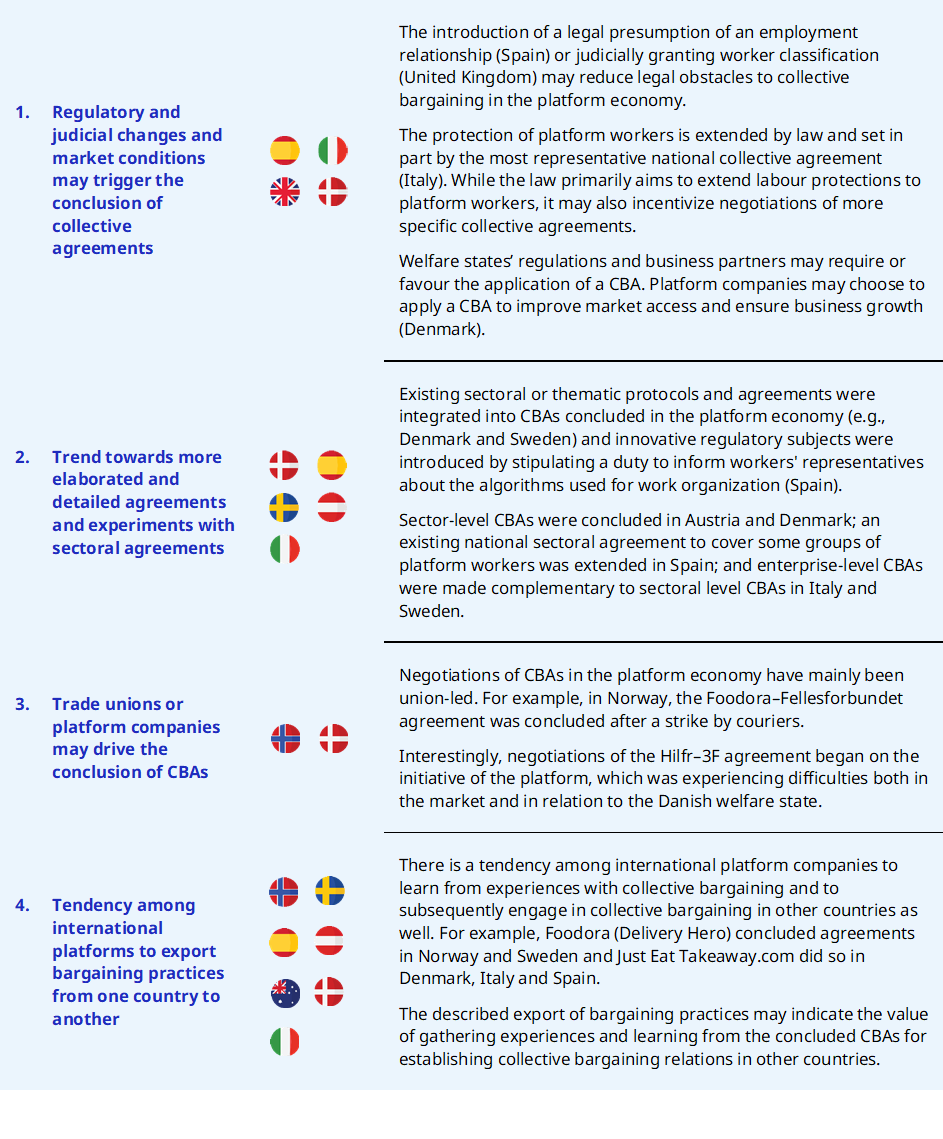

Chapter 3 provides a content analysis of a “first group of collective agreements” covering digital labour platforms. It benefited from a commissioned preparatory background study and reviews by academic researchers. In total, 11 collective agreements have been identified covering digital labour platforms in Austria, Chile, Denmark, Italy, Norway, the Republic of Korea, Spain and Sweden. For the majority of the collective agreements identified, the original texts were collected, translated and analysed for this study. All collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) regulate working time and include provisions on hourly wages and incentive-based payment structures. All identified CBAs apply to platform workers in an employment relationship, who often work in the food delivery sector in Europe.

The Conclusion provides a number of remarks based on the experiences described and analysed in Chapters 1 to 3.

For what reasons and in which forms do platform workers engage collectively? An empirical snapshot

Key findings

Figure

Overall, the analysed observations in the country surveys indicate the existence of the need for and motivation of location-based platform workers to come together and engage with each other in some form to improve their working conditions – irrespective of the alleged individualistic character of the digital labour market and uncertainties about their employment classification and corresponding labour rights in many countries.

This chapter provides an empirical snapshot of the ways and forms in which platform workers engage with each other. In addition, the analysed data shed light on their motivations to join different types of groups and the effects of such membership. The chapter analyses data on workplace solidarities compiled through country surveys commissioned by the ILO. Most of the findings are limited to location-based platform workers. The last section of the chapter sheds some light on the workplace solidarities of online web-based platform workers.

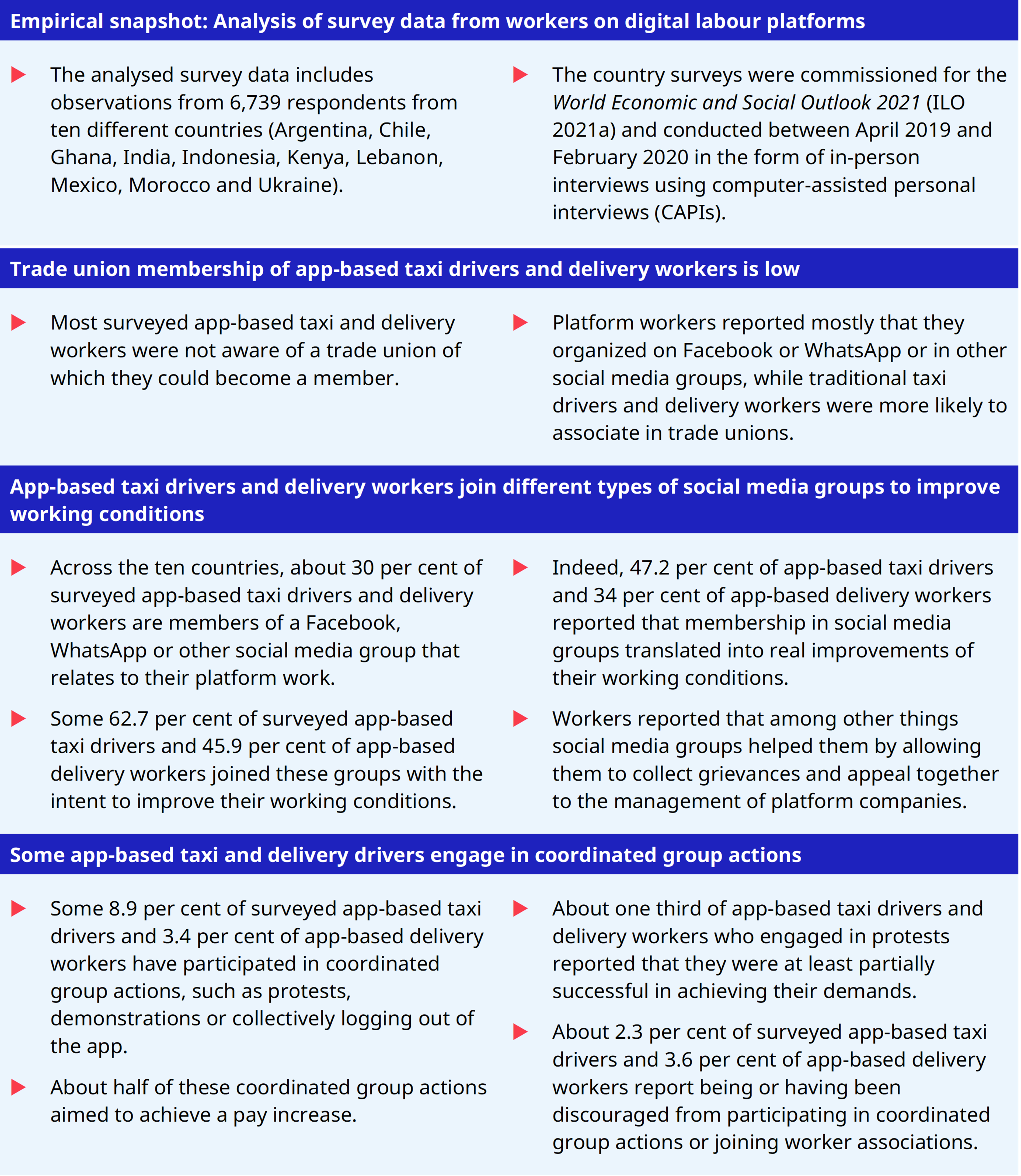

The analysed survey data includes observations from 6,739 respondents from ten different countries, with a focus on developing and emerging economies (Argentina, Chile, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco and Ukraine).20 The country surveys were conducted between April 2019 and February 2020 in the form of in-person interviews using CAPIs. While the majority of questions in the survey were quantitative, some were qualitative and allowed for open-ended textual answers.

There are no comprehensive official statistics on platform workers, including their number and characteristics. Hence, there was no base from which a random sample could be drawn. In this context, the primary objective of the survey was to achieve a sample that would be as representative as possible of the target population of platform workers. The target population consisted of any worker aged 18 years or older who had been working in the taxi or delivery sector for at least three months. The criterion of working in the sector for three months was used to ensure that the worker could provide meaningful responses.21

The respondents to the surveys were grouped into four categories: (1) app-based delivery workers, (2) app-based taxi drivers, (3) traditional delivery workers and (4) traditional taxi drivers. The survey design allows for comparisons of findings between app-based and traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers.22

Motivations for engaging with other workers and joining different types of groups to improve working conditions on location-based digital labour platforms

In general, common interests and a shared identity are regarded as prerequisites of an effective collective representation of workers

However, a general finding from the data collected through the country surveys is that across the ten countries, a significant proportion of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers engage with each other in some form. This happens despite the alleged individualistic and dispersed character of the digital labour market, in which workers are isolated from each other. The interaction and engagement may happen on a non-regular basis through unplanned day-to-day encounters. In this regard, about 82 per cent of surveyed app-based delivery workers and 66 per cent of app-based taxi drivers reported that they speak with other drivers about their work experiences at least multiple times a week. These exchanges may happen in person at taxi stands, parking lots, tea stands or eating places, or may occur digitally via cell phones and social media.

In addition, a significant share of app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers joined different types of social media groups with the motivation to improve their terms and conditions of work. The organization of platform workers in different types of groups and associations23 is the focus of this chapter. The following sections summarize the information on workplace solidarities gathered from the above-mentioned ILO country surveys under four main findings.

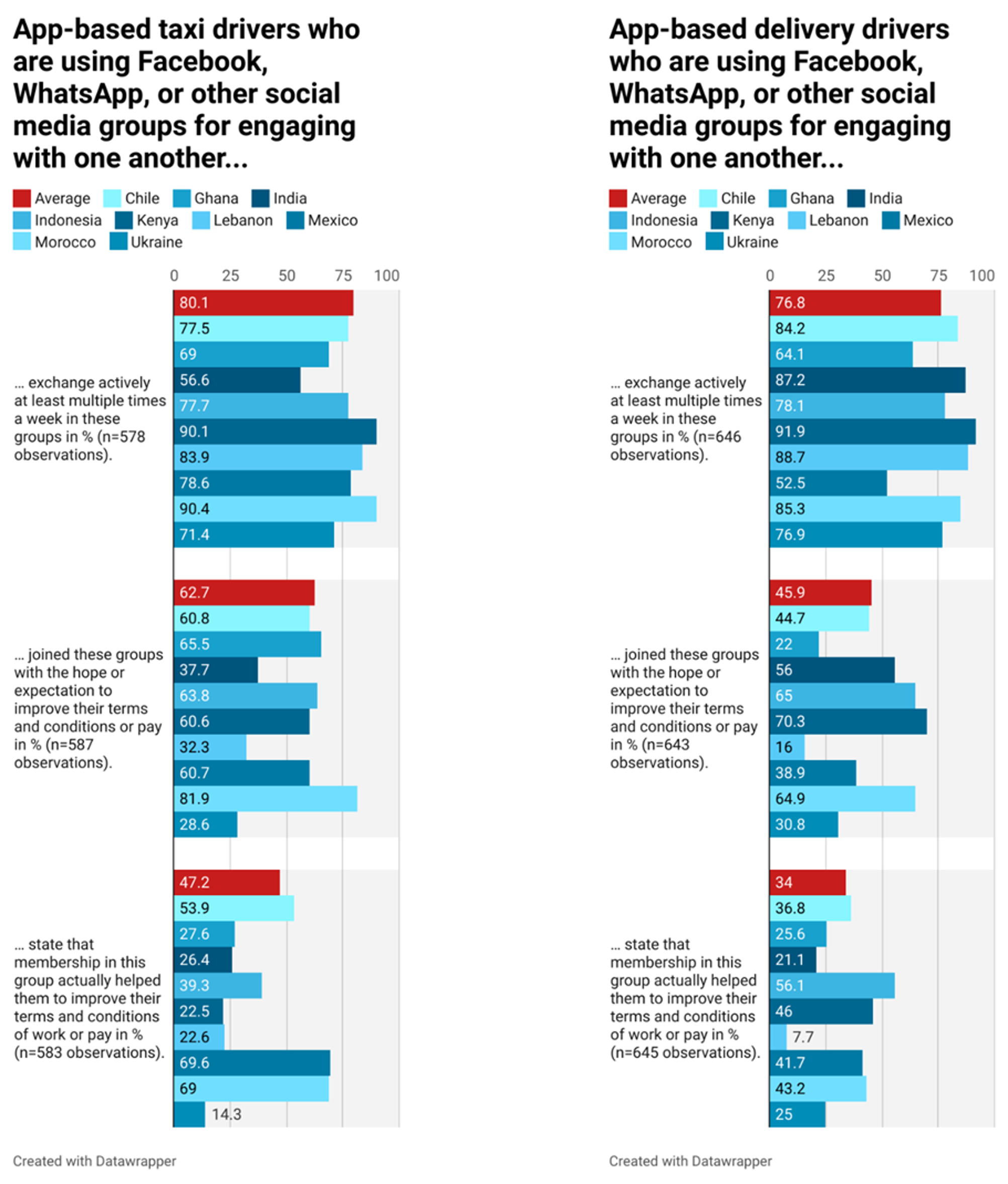

Finding 1: Location-based platform workers are often not aware of trade union organizations

-

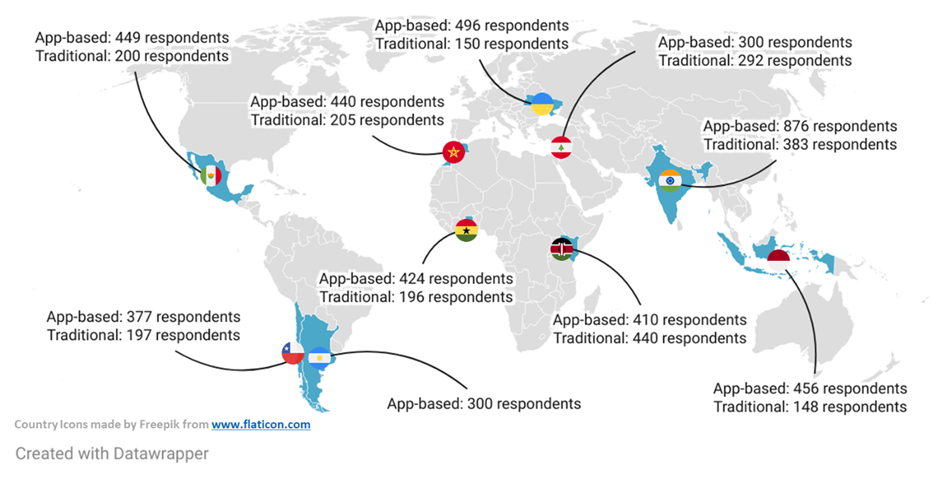

A large majority of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers were not aware of a trade union organization of which they could become a member. Even if location-based platform workers were aware of the respective organizations, they seldom decided to become a member. This reveals a major difference from surveyed traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers, who were much more likely to be a member of a trade union. For example, in Ghana and Indonesia traditional taxi drivers were 7 times and in India as much as 26 times more likely to be a trade union member than their app-based counterparts in the surveys. 24

About 85.7 per cent of surveyed app-based delivery workers and 68.4 per cent of app-based taxi drivers reported that they were not aware of a trade union organization of which they could become a member (see figure 2). This implies that some surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers were aware of a trade union organization of which they could become a member. However, it also appears that the majority of them decided not to join the organization.25

Figure 2: Awareness of a trade union organization

Trade union membership of app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers is low

Overall, the reported level of trade union membership of app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers was low in the country surveys. Where respondents reported being a union member, this mostly involved membership of newly established trade union organizations that primarily organize app-based workers, such as the “Online Drivers Union” or the “Uber Drivers Association”. A majority of union members reported that they actively participate in the union’s activities multiple times a week. Surveyed app-based taxi drivers are also more likely to be a member of a trade union than app-based delivery workers – while the unionization rates for both categories were low among those surveyed.26

Surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers who had joined a trade union organization were also more likely to report improved working conditions in comparison to those who had joined a social media group.27 Regarding the benefits of trade union membership, app-based workers indicated that the information and grievances they voiced were forwarded by the union to the platform company. Respondents also valued the exchange with other workers in order to receive advice on basic labour rights, organize protests, receive information about governmental regulations on the platform economy and receive financial support in difficult times (for example, obtaining access to insurance schemes through the trade union).

Comparisons show that traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers are more likely to be trade union members

Overall, surveyed traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers were much more likely to be trade union members than their app-based counterparts. However, the cross-country average of trade union membership hides important differences among the ten countries in the sample. Reported membership rates for traditional taxi drivers ranged from 0 per cent in Kenya and Mexico to 40.9 per cent in India.28 Country differences range from Lebanon, where traditional taxi drivers were 1.2 times more likely than app-based taxi drivers to be trade union members, to India, where traditional taxi drivers were 26 times more likely than app-based taxi drivers to be a member of a trade union. Only very few surveyed traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers reported membership of a trade union organization that also had app-based workers among its members.

Finding 2: App-based taxi drivers and delivery workers are using different types of social media groups to come together with the motivation to improve their terms and conditions of work

-

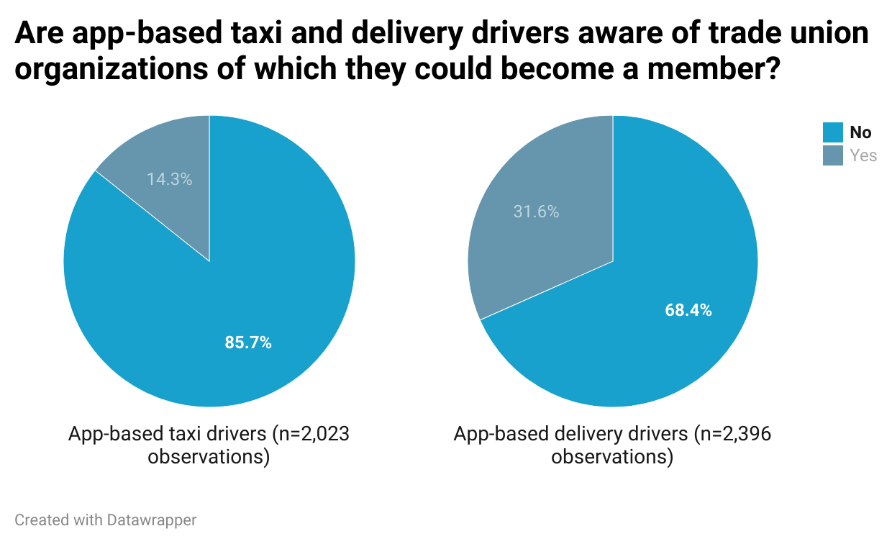

Among those surveyed, about 28.4 per cent of app-based taxi drivers and 33.3 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported membership of a “Facebook, WhatsApp, or other social media group”. A large proportion of app-based taxi drivers (80.1 per cent) and app-based delivery workers (76.8 per cent) who are members exchange actively at least multiple times a week in these groups. Of these workers, a large share of app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers joined these groups with the hope or expectation to improve their working conditions. A sizeable proportion of them reported that membership in these groups translated into real improvements of their working conditions (see figures 3 and 4).

Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups provide a platform for almost one third of the workers to discuss problems and support one another

Among those surveyed, app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers who are members of a Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media group reported that such groups mostly provide a platform to discuss the problems they face and to support and help each other. This often includes information on traffic and road security or controls by the authorities. The groups also provide support in cases of emergencies or accidents or for car/bike repairs, sales and rentals. In social media groups for bicycle delivery workers, information is also exchanged on weather conditions.

|

Figure 3. Engagement of app-based taxi drivers in social media groups, by country |

Figure 4. Engagement of app-based delivery workers in social media groups, by country |

In several groups, information is exchanged on how to improve earnings (e.g. information on high-demand areas, best routes, fares and bonus schemes in the apps). Some groups also provide information on fraudulent orders or customers and technical problems encountered with the app. The groups provide forums in which drivers can get advice from (more senior) peers on these issues. In addition, respondents reported that several groups provide platforms for socializing (jokes, memes) and moral support among app-based workers.29

Some of these groups were characterized by respondents as providing information on political lobbying activities of workers and their organizations in order to defend their interests; demonstrations and strikes; cooperation and solidarity between members; charity collections; how to defend the rights of app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers; and discussions of new regulations in digital platform work in their respective countries.

Motivations and reasons differ among workers for engaging with each other through Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups

Respondents were also asked about their motivations and reasons for engaging with each other through Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups. At the cross-country level, about 62.7 per cent of app-based taxi drivers and 45.9 per cent of app-based delivery workers who joined these groups did so with the hope or expectation to improve their terms and conditions of work.

However, large variations may be observed between different countries. For example, in Lebanon about 16 per cent30 and in Kenya about 70.3 per cent of app-based delivery workers joined a Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media group with the expectation to improve their workings conditions (see figure 4). Such variations between countries can also be observed for app-based taxi drivers (see figure 3).

Participation in Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups: Impacts on terms and conditions of work

About 47.2 per cent of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and 34 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported that participating in Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups helped them to improve their conditions of work. There are considerable variations among the ten countries (see figures 3 and 4).

Many of the surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers reported that social media groups provided them with helpful advice on how to improve earnings when starting to work on the applications. This included learning which hours and areas it was best to work in and further tips about how to earn more money and how to get more orders. Some workers also reported that the groups helped them to collectively achieve better conditions, such as lower highway tolls or better payment modalities for the use of highways in some countries.

Of those who joined these groups, several of the surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers reported that participating in Facebook, WhatsApp or other social media groups helped them to receive support from other drivers in cases of emergencies (such as car accidents or being robbed). For example, one respondent reported that when he had an accident other members of the group came to help and called his family. In addition, the drivers value social media groups for helping them to learn more about work processes, dangerous areas and situations or how to deal with problematic customers. The responses varied depending upon the country.

In addition, few workers reported that social media groups helped them to improve working conditions by collecting grievances and appealing together to the management of the platform companies. Grievances are collected by the “group admin” or a “chairperson”, who sends them to the platform company or sets up meetings and discussions with the management of the platform company. It was also reported that such groups helped workers to improve working conditions by learning about their rights, organizing protests and marches, raising awareness of precarious working conditions among the wider public and collectively lobbying at the political level for improved regulations and working conditions.

Finding 3: App-based taxi drivers and delivery workers engage less frequently in coordinated group actions than traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers

-

While a significant number of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers organize on Facebook or WhatsApp or in other social media groups with the motivation to improve their conditions of work, they rarely participate in collective actions such as protests, demonstrations or collectively logging out of the app to effectively represent their interests. This finding relates to the question of how membership in social media groups translates into improvements of working conditions for location-based platform workers.

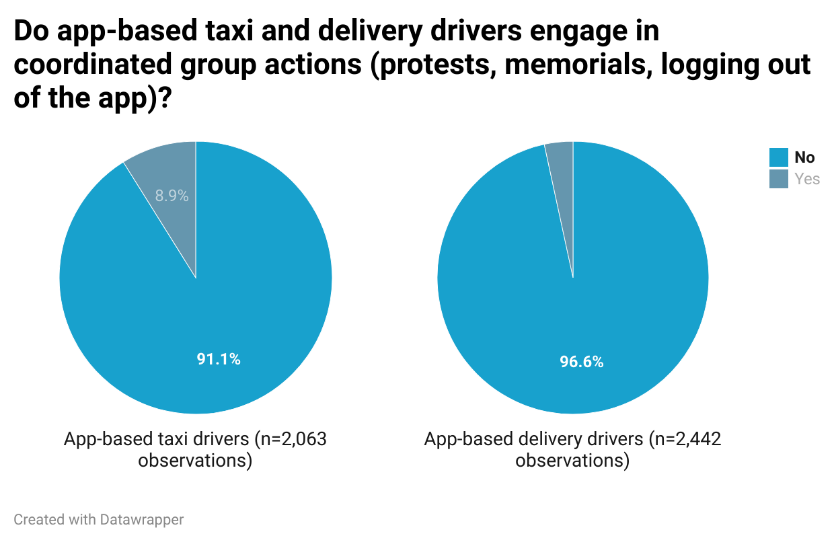

Figure 5: Engagement in coordinated group actions

At the cross-country level, about 8.9 per cent of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and 3.4 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported that they had participated in coordinated group actions, such as a protest, a demonstration or collectively logging out of the app. Again, there are substantial variations between different countries. In Chile (28.6 per cent), India (13.9 per cent) and Morocco (33.3 per cent), a significant fraction of surveyed app-based taxi drivers have participated in coordinated group actions such as a protest, a demonstration or collectively logging out of the app. In other countries, such as Indonesia (2.7 per cent), Lebanon (1 per cent) and Mexico (0.5 per cent), almost none of the surveyed app-based taxi drivers have participated in coordinated group actions. This indicates again the importance of country-specific circumstances and industrial relations systems.

How did app-based workers find out about coordinated group actions?

Most app-based workers reported that they found out about coordinated group actions through Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram or other social media groups. It should be noted here that this explicitly also includes social media groups operated by trade unions. A substantial proportion of app-based workers learned about coordinated group actions through colleagues. Few app-based workers found out about such actions in the newspapers or on TV.

What were they trying to achieve?

About half of the coordinated group actions by app-based workers aimed to achieve a pay increase. The demands included increased fares, a reduction of the commission fees deducted by the platform companies, or redefining bonus and incentive pay structure. Some coordinated group actions related to the legal rights of platform workers. Several of them also sought to achieve recognition for app-based workers’ organizations or union status. In addition, app-based workers used coordinated group actions to protest for greater job security; against account blockings; to help and support the cases of individual workers; to raise awareness of their working conditions after severe accidents of app-based workers on bicycles; or to protest that some workers on bicycles did not have suitable equipment to be protected against injuries and adverse weather conditions.

Were they successful?

On being asked whether coordinated group actions were successful, about one third of the app-based workers who participated in one reported that they had been (partially) successful in achieving their demands. Achievements included increased fares; media recognition such as on TV, in print media or the radio; or the establishment and registration of trade unions for app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers.

About two thirds of the app-based workers who participated in a coordinated group action reported such actions to have been unsuccessful or that results still remained to be seen. App-based taxi drivers and delivery workers often noted that there had been no response from the platform company or that nothing had happened at all. In addition, workers also reported some challenges in organizing as often an insufficient number of app-based workers had participated in a coordinated group action, such as collectively disconnecting from the app at a specific time. Few app-based workers reported threats, such as deactivation of accounts, if they participated in a coordinated group action.

Traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers are more likely to participate in coordinated group actions than their app-based counterparts

About 17.3 per cent of surveyed traditional taxi drivers and 9.3 per cent of delivery workers reported having participated in a coordinated group action, such as a protest or a demonstration. Also, for traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers there are large variations among countries. In Chile (28.6 per cent), India (42.4 per cent) and Morocco (28.2 per cent), a significant percentage of traditional taxi drivers reported that they had participated in coordinated group actions. In other countries, such as Ukraine (2.7 per cent), Indonesia (2.7 per cent) and Lebanon (0.0 per cent), only very few traditional taxi drivers reported such participation. Also, for traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers the variations in the level of their engagement in such actions indicates the importance of country-specific legal and practical circumstances and industrial relations systems.

Finding 4: Some app-based and traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers reported being or having been discouraged from participating in coordinated group actions or joining worker associations or groups that represent the interests of workers

-

The country surveys show that some app-based workers feel discouraged from participating in coordinated group actions or engaging in worker associations. Often workers who reported feeling discouraged indicate that they intend to only work temporarily as an app-based worker and a lack of concrete impact of collective actions on working conditions. Few surveyed app-based workers reported feeling discouraged by the management of platform companies from participating in coordinated group actions or engaging in worker associations.

About 2.3 per cent of surveyed app-based taxi drivers and 3.6 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported being discouraged or having been discouraged from participating in collective action or joining any worker association or groups that represent their interests. These numbers need to be seen in the broader context of low unionization rates and the low rates of engaging in coordinated group actions. In a subsample of app-based workers who actually participated in coordinated group actions, about 8.8 per cent of app-based taxi drivers and 18.8 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported being discouraged or having been discouraged from participating.

The reasons for being discouraged from participating in group actions varied. It was either because the discussions in social media groups were time-consuming, often without any concrete actions; or they were discouraged by colleagues to participate; or they regarded their app-based work as something temporary and they just wanted to work and earn money. Individual app-based workers reported being discouraged to join in group action by circumstances that might be related to their migration status.

Few of the surveyed app-based workers reported that they were discouraged from participating in coordinated group actions through group messages by the management of platform companies and feared the threat of the deactivation of their accounts. Some of them reported that they were explicitly warned not to create or join any social media groups relating to the platform company.

Comparison to traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers

In comparison, 7.6 per cent of surveyed traditional taxi drivers and 3.5 per cent of traditional delivery workers reported being or having been discouraged from participating in collective actions or joining any worker association or groups that represent their interests. In a subsample of surveyed traditonal workers who actually participated in coordinated group actions, about 16.5 per cent of traditional taxi drivers and 3.1 per cent of traditional delivery workers reported being discouraged or having been discouraged from participating. It needs to be taken into consideration that traditional taxi drivers and delivery workers are also more likely to engage in coordinated group actions and much more frequently join trade unions in comparison to their app-based counterparts. This might partly explain why they also more frequently report being or having been discouraged from participating in collective actions or joining worker associations or groups that represent their interests.

Motivations for exchanging with other workers on online web-based digital labour platforms

Workers on online web-based platforms perform tasks on microtask, freelance and competitive programming platforms. Challenges for the organization of workers are amplified in the online web-based platform economy in comparison to the location-based platform economy. Workers on online web-based platforms are not necessarily located in the same geographical space with their requesters and directly compete with other platform workers to access the tasks offered by the platform, while often suffering from a lack of shared professional identity among themselves

Since 2017, several surveys have been undertaken by the ILO to better understand working conditions on online web-based platforms. This includes a global survey of crowdworkers on five major microtask platforms (2017); a global survey of workers on freelance and competitive programming platforms (2019–2020); and country-level surveys of platform workers in China and Ukraine (2019).31 Based on the survey responses, the following sections analyse how workers on online web-based platforms engage with each other and whether trade union organizations play a role in this regard.

A substantial number of crowdworkers on microtask platforms turn to online forums for mutual support

The majority of crowdworkers (58 per cent) reported in the surveys that they turn neither to unions, solidarity groups, online forums or any other groups as a place to discuss problems or consult for advice related to crowdwork or to receive some form of protection.

Still, about one third of the surveyed crowdworkers turn to online forums to discuss problems or consult for advice related to crowdwork. Many of these online forums, such as Turkopticon, TurkNation and TurkerHub, are connected to specific platforms, such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). In addition, several crowdworkers reported using Facebook or Reddit groups to discuss problems or consult for advice. Some of the forums referenced by crowdworkers have a regional focus, such as the “Indonesian Online Worker Forum” or the “Online Microworkers Nepal”. However, most of the forums seem to attract an international audience of crowdworkers. Crowdworkers reported that they use online forums for mutual support, including to discuss available work and problems with tasks and to give general support. The exchanges in online forums included questions about companies and individuals who offer work on web-based online platforms and their reliability. Overall, crowdworkers used online forums mostly to support and help each other and not for discussing working conditions or organizing (online) protests.

Only few crowdworkers on microtask platforms turn to trade unions for support

A small number of crowdworkers reported that they had turned to trade unions to discuss problems, consult for advice or receive some form of protection related to crowdwork. The trade unions mentioned by respondents operate in different regions of the world and included the Sindicato de Empleados de Comercio (Argentina); the Canadian Freelancer Union and Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (Canada); IG Metal and ver.di (Germany); the National Joint Council of Action of the National Defence Workers’ Federation (India); the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) (Spain); Unite (United Kingdom); and the Freelancers Union (United States).

Freelance workers on online web-based platforms seldom engage with trade unions and professional associations

Workers on surveyed freelance platforms reported that they routinely use a number of online resources when engaging in platform work, including YouTube (60.4 per cent), blogs (36.1 per cent), online courses or universities (43 per cent), forums or other online communities (48.3 per cent) and platforms that provided help and support on a specific topic (38.5 per cent).

However, a large majority of workers (82.6 per cent) reported that they did not turn to labour unions, trade unions, professional associations or organizations or other organizations for their work on labour platforms. About 12.9 per cent of workers reported that they turn to professional associations or organizations to discuss their freelance work. This mostly included groups on Facebook and LinkedIn, as well as professional organizations such as the Online Professional Workers Association (OPWAK) formed in 2019 in Kenya. Only very few freelancers on online freelance platforms reported that they had turned to labour unions as additional resources when performing their tasks.

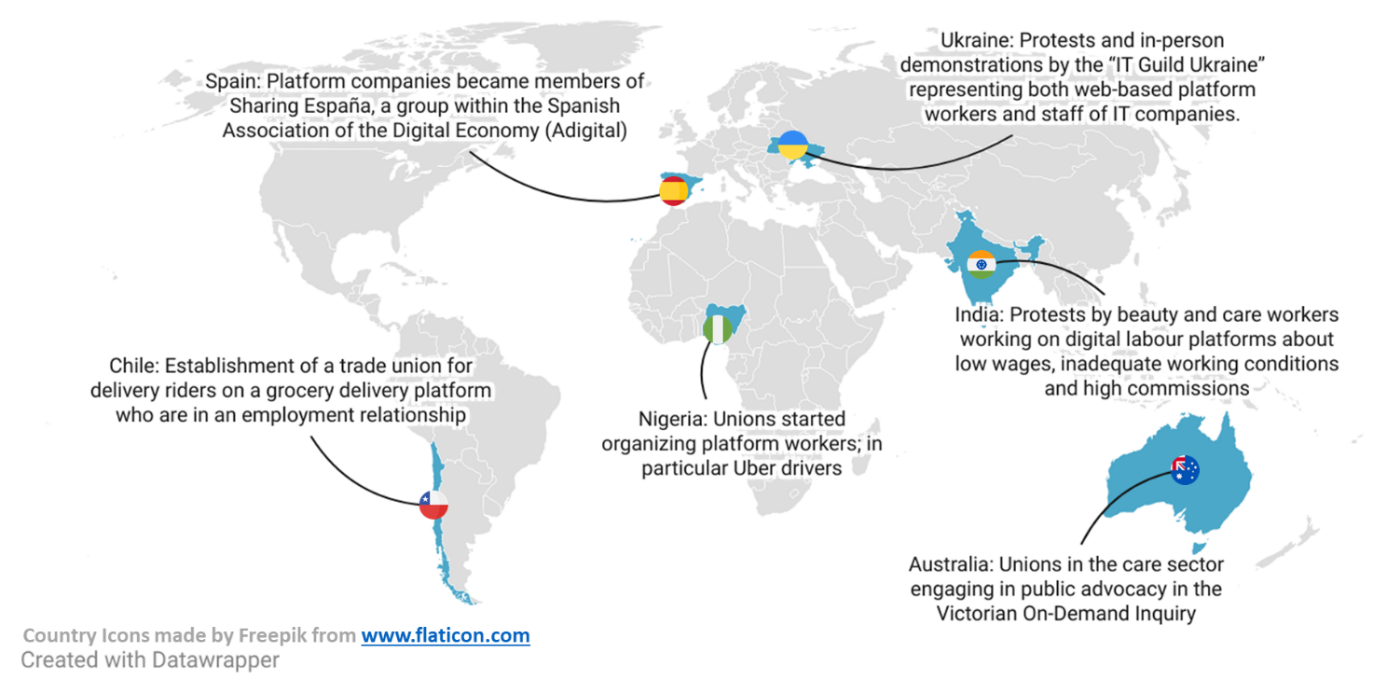

Initiatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations and self-organization of workers in the platform economy

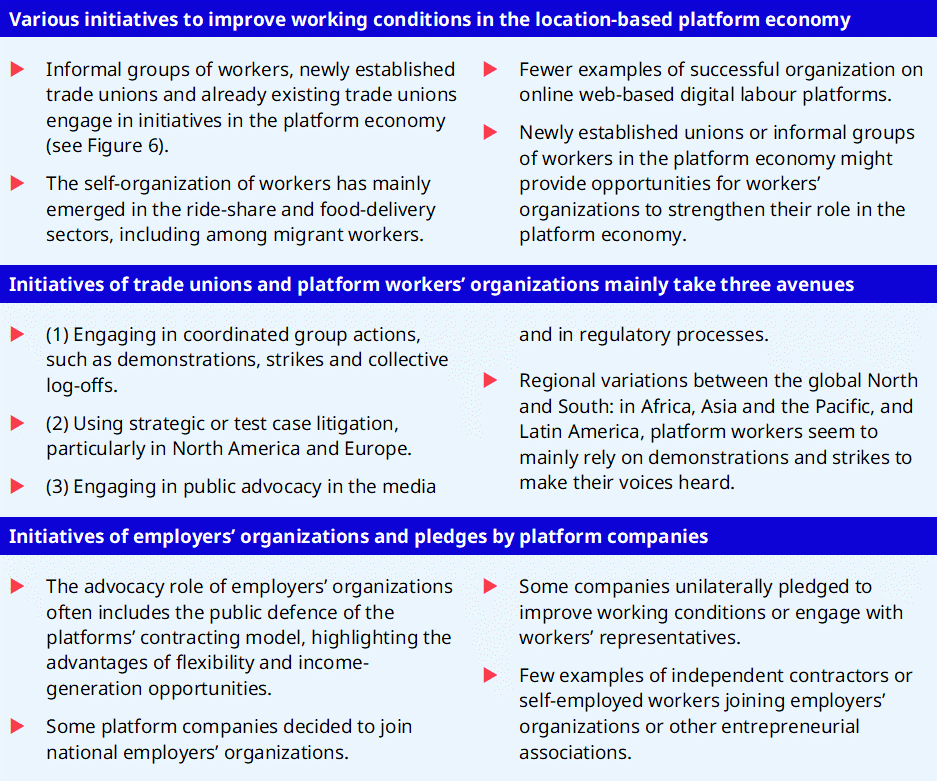

Key findings

Figure 6: Country case studies commissioned by the ILO

In Ghana, it was the non-payment of bonuses that first motivated app-based drivers to organize – “the bonuses weren’t coming and we realized that it was because nobody was speaking for the drivers”. In addition, drivers felt that the non-transparent deactivation of drivers by platform companies was frustrating (Akorsu et al. forthcoming).

Chapter 1 showed through country surveys that location-based platform workers are generally motivated to come together and engage with each other in some forms to improve their working conditions. Building on that general finding, the purpose of this chapter is to identify and document in more detail concrete examples “on the ground” from different regions of the world. The examples describe the efforts of employers’ and workers’ organizations to reach out to workers in the platform economy and how these workers self-organize with a view to influencing their terms and conditions of work.

Country examples are taken from case studies commissioned by the ILO in Australia32, Chile33, India34, Nigeria35, Ukraine36 and Spain37. In the preparatory phase of the research project (February to April 2021), interviews with representatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations and experts from academia and civil society were conducted. These helped to identify important developments and case studies in different regions of the world. Based on those initial interviews, countries were selected for analysis based on their innovative legislative and judicial developments, while ensuring regional balance.

Overall, for the country case studies, interviews with about national 20 informants – who ranged from platform workers and representatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations to academic researchers – were conducted by the contributors to this chapter. In addition, it draws on existing case studies in the academic and grey literature and in news reports.

Box 4: Realizing the opportunities of the platform economy for businesses and workers

This chapter shows that coordinated group actions (including demonstrations, strikes and collective log-offs) have emerged in all regions of the world, indicating the potential value of dialogue and collective bargaining for social peace in the platform economy. In general, dialogue and collective bargaining in the platform economy is more likely to produce concrete results where it is supported by solid legal and regulatory frameworks and is engrained in countries’ industrial relations traditions. This general consideration may help to explain the notable regional variations that can be observed between the country examples from the global North and South that are presented in this chapter.

Initiatives of workers’ organizations in the platform economy

Informal groups of workers, newly established trade unions and already existing trade unions are active in the platform economy. They engage in coordinated group actions (demonstrations, strikes and collective log-offs); use strategic or test-case litigation; and engage in public advocacy in the media and regulatory processes. The examples also show trade union activism in the platform economy on behalf of traditionally disadvantaged groups of workers, such as migrant workers. Overall, the country examples show that location-based platform workers have adopted a greater variety of strategies than online web-based workers. The notable differences in the organizational efforts between countries in the global North and South are also discussed below.

Establishing workers’ organization in the platform economy

ILO surveys in ten countries found that the reported numbers for trade union membership of workers in the platform economy are low overall (see Ch. 1). However, in some instances platform workers have established new organizations and sometimes they have joined existing unions

Platform workers establish new workers’ organizations

In different parts of the world, the establishment of new workers’ organizations can be observed. However, the self-organization of platform workers going beyond social media groups has mainly emerged in the ride-share and food-delivery sectors (ILO 2022a).

The types of organizations in which workers in the platform economy organize are very diverse. The newly established organizations take different legal forms and have different levels of organizational maturity. For example, in Chile some newly established organizations collect union dues, have established statutes or bylaws, have quota systems and are represented by elected representatives.38 Other organizations do not yet have statutes or guiding principles and membership registers and resemble more informal groups (see Box 5 for the names of newly established organizations and their organizational scope in Chile).

Particularly in countries with a conducive regulatory environment, formally registered trade union organizations and works councils have emerged in the platform economy.39 The interactions between already existing trade unions and these newly established workers’ organizations can be shaped by competition and conflict or by cooperation and mutual support. Box 5 illustrates with concrete examples the establishment of workers’ organizations and in some cases indicates how those new organizations engage with existing trade unions.40

Box 5: Examples of newly established workers’ organizations in location-based platforms

-

In Australia, the Rideshare Driver Network started as a private Facebook group in 2018 and is now an incorporated not-for-profit organization aimed at improving the working conditions and pay of Australian rideshare drivers.41 It is a founding member of the International Alliance of App-based Transport Workers and has run campaigns jointly with the Transport Workers' Union.

-

In Brazil, the Sindicato dos Motoristas de Transporte Individual por Aplicativo organizes drivers in the platform economy. The organization is active in different states of the country (such as Rio Grande do Sul42 in the south and Rondonia in the north-west43). In some states, the newly established organization has collaborated with the Central Única dos Trabalhadores and organized strikes in several cities together with that trade union.

-

In Chile, 44 the following workers’ organizations of workers in the platform economy have been established: Riders United Now (established in January 2020 and organizing workers from Order Now and Rappi); Penquista Delivery Drivers (established in January 2018 and organizing workers from PedidosYa and Cornershop); Cornershop Union (established in July 2016 and organizing workers from Cornershop); Asociación Gremial de Conductores de Aplicación (ACUA) (organizing workers from Uber and DiDi); UBER Independent Workers Union (established in 2018 and organizing workers from Uber); and Shopper freelancer (established in 2020 and organizing workers from Cornershop).

-

In Ecuador 45 and Peru,46 different groups on social networks create collaborative spaces for platform workers, which may constitute the start of the continuous formalization of newly emerging workers’ organizations in the platform economy in these countries.

-

In Georgia, self-organization efforts led to a demonstration, after which workers announced the formation of a trade union for workers for the food delivery apps Glovo, Wolt, Bolt Food and Elvis, as well as the Yandex and Bolt taxi services.47 The main goals of the trade union are to secure employment contracts for couriers, including health insurance coverage, overtime and bad weather compensation, as well as paid holidays.

-

In Ghana, several app-based drivers’ associations have been identified, including Ghana Online Drivers Union; Ghana Online Drivers Association; Online Drivers’ Union of Ghana; Smart Drivers Union (SMART); Online Family Drivers Union; Online Drivers’ Partners Association; Ride Share Online Drivers Union; and Super Car Owners (Akorsu forthcoming) . These associations have different organizational structures. While some have statutes and a system for dues collection, others are currently drafting constitutions and collect membership contributions only when the need arises. Some are affiliated to the Trades Union Congress of Ghana. Members of two of the associations pay a weekly subscription through mobile money transfers.

-

In Indonesia, it is reported there has in recent years been an “astonishing” capacity for self-organizing, mutual-aid and grass-roots community participation of app-based transport drivers

(Ford and Honan 2019) . In 2022, it was reported that there are hundreds of informal food-delivery driver communities, in which workers check in with each other daily for advice for anything from the best routes for a delivery to strategies for improving their earnings.48 -

In Nigeria, the Drivers and Private Owners Association (PEDPA)49 was formed in 2019 and is affiliated with the Trade Union Congress.

-

In Spain, organizations of platform workers began to emerge, such as RidersxDerechos in July 201750 or FreeRiders. These new associations collaborate with existing assocations, such as Intersindical Valenciana51 or Intersindical Alternativa Catalana52 or with the biggest trade unions in Spain – the UGT and Comisiones Obreras (CCOO). RidersxDerechos is not a trade union but has been constituted as an association and registered its name and logo. This association cooperates with already established trade unions for legal issues. In addition, associations of economically dependent autonomous workers have started to emerge, defending the classification of workers as self-employed from 2018 onwards. This includes the Spanish Association of Messenger Riders, the Professional Association of Autonomous Riders and the Association of Autonomous Riders. In 2020, Repartidores Unidos or Riders United was founded, which defends collaborative work rather than being a riders’ association.53

-

In Uruguay, the workers’ organization Sindicato Único de Repartidores, made up exclusively of delivery workers, was founded in 2019.54 The establishment of the organization was supported by the Federación Uruguaya de Empleados de Comercio y Servicios. In addition, the ACUA, an association of drivers in the platform economy,was established.55

-

In the United States, workers’ organizations in the platform economy might take the form of union-affiliated guilds such as the Independent Drivers Guild representing Uber drivers

(Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas 2018) .

Existing trade unions reaching out to workers and their organizations in the platform economy

Box 5 showed that many newly established unions of platform workers are in regular contact or are supported by already existing trade unions. In several country examples, it may be observed that already existing and well-established trade unions provide support and access to institutional power for the emerging organizations of platform workers (see also Webster et al. 2021). Box 6 highlights some concrete examples of how existing trade unions reached out to workers in the platform economy and their organizations.

Box 6: Trade unions reaching out to workers and their organizations in the platform economy

-

In Georgia, following protests by platform workers the Georgian Trade Union Confederation expressed solidarity and support and discussed potential methods of assistance for existing unions.56 In addition, civil society organizations supported the couriers’ demands and their readiness to provide legal assistance if needed.57

-

In Kenya, the Transport and Allied Workers’ Union of Kenya (TAWU-K) is a registered union affiliated to the Central Organization of Trade Unions and the International Transport Federation (ITF). TAWU-K developed a new organizing and recruitment strategy designed specifically for platform workers. Based on this new organizing strategy, the union reported that it had recruited more than 2,000 app-based drivers and expanded its activities from Nairobi to Mombasa, Nakwu, Kisumu, Edoret and Mt Ken (Webster and Mesikane 2021).

-

In Nigeria, the Road Transport Union started organizing platform workers, in particular Uber drivers.58

-

In Spain, interviewed trade union leaders observed that the distance that existed between the newly established workers’ organizations in the platform economy and already existing unions has narrowed, establishing a trend towards harmonization, convergence of positions and collaboration. When it comes to contacting workers, who provide services on platform companies, the already existing trade unions have collaborated not only with these new organizations but also with other more established organizations, such as immigrant women’s associations, in order to reach out to persons who provide housekeeping services via platforms.59

-

In Switzerland, in the canton of Geneva platform delivery workers turned to the unions SIT and Unia to defend and represent them in a dispute with a platform company. Through social dialogue and the involvement of existing trade unions, the number of eventual lay-offs were considerably reduced in the end.60

-

In Ukraine, the Federation of Trade unions of Ukraine (FPU), the largest union federation in Ukraine, has expressed deep concerns about the platform economy. The FPU Strategy for 2021–2026 includes the objective of formalizing the labour of platform workers and granting them the right of collective bargaining.61

Box 7 describes in detail how an already existing trade union supported the establishment and functioning of newly established trade unions for workers in the platform economy in India. The example illustrates how trade unions and newly established unions for platform workers can collaborate.

Box 7: A closer look: Trade unions reaching out to platform workers in India

In India, the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) has supported a number of initiatives for platform workers to organize, including the All-India Gig Workers Union (AIGWU), which is undertaking cross-sectoral efforts to organize platform workers. CITU supports AIGWU’s organizing activities, playing an advisory role in framing worker demands and strategies. CITU has also supported its state-level unions of transport workers through the strategic inclusion of platform workers as members under separate councils or subcommittees.62

Apart from affiliations with existing unions, the formation of purpose-specific workers’s organizations has been viewed as a way to strengthen collective bargaining and coordination efforts among platform workers. The Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT) is one such organization, which functions as a national-level federation of state-level affiliate unions for app-based transport and delivery workers across ten cities in India.63 IFAT has engaged directly with various stakeholders through various techniques, including by large-scale public demonstrations64, direct negotiations with companies and the Government, filing public interest litigation,65 producing research66 and engaging on public and semi-public forums.67 While IFAT and AIGWU have been able to secure formal trade union registration, the registration process was reportedly not straightforward.

Most of the newly established workers’ organizations are found in the app-based transportation and delivery sector. Box 8 describes how workers’ organizations explore the possibilities for organizing workers in another sector.

Box 8: Workers’ organizations reaching out to care and beauty workers in the platform economy in India

In Northern India, according to a grass-roots organizer of platform workers women careworkers are very difficult to organize, but there is huge interest from the CITU, which has a coordination committee of working women that reviews gender questions. In Noida, there are many platform company start-ups, with 300–400 workers doing massage, beauty work and other related services. The All India Domestic Workers Association surveyed them to see what issues they are facing in the pandemic. Work on organizing women platform workers is very new, not yet formal and currently at the stage of doing small interventions to see which organizing strategies may be successful.

Box 9 describes in more depth the establishment of a trade union for workers in a grocery delivery platform who are in an employment relationship and describes the relationship with existing unions in Chile. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the president of the newly established trade union was elected as leader of the national organization of trade unions, the Central Unitaria de Trabajadores de Chile (CUT) in 2021. Moreover, the example illustrates the differences arising from the classification of workers when establishing an organization.68

Box 9: A closer look: Cornershop union of platform economy workers in Chile

In Chile, the Cornershop trade union was established in December 2016. The establishment of the union was enabled by the fact that in the beginning of Cornershop’s operations, all staff who worked in the different functions at the platform company were in formal employment relationship in Chile. The union members organized themselves in accordance with the powers granted to them by the Labour Code as a company union, developing internal activities to strengthen and protect members, participating in discussions to improve working conditions, occupational safety and other matters.

The establishment of the organization was similar those of unions in other industries. It started with discussing common problems that afflicted the workers. Discussions began to increase in scope and came to public light first with the formal constitution of the union and secondly with the presentation of a petition to conclude a collective agreement presented to the company. The trade union and Cornershop concluded collective agreements in 2017 and 2019 that apply to the employed shoppers of the platform company (see Ch. 3).

Relationship with already existing trade unions: The union has established permanent relations with other organizations, including the Lider-Walmart hypermarket workers’ network, with whom they share office spaces. Building on this relationship, the union’s participation in the Trade and Financial Services Unions Coordinating Committee is maintained to this day. The president of the Cornershop union ran for a leadership position in the CUT and was elected as national leader of the organization for the period 2021–2024.69 This is one of the first times that the leader of a newly established union in the platform economy has held an elected leadership position in an existing union.

Differences arising from the classification of workers: Cornershop started to hire delivery drivers as independent contractors. The change in the contracting system with the shoppers generated a second organization on the platform called Shoppers Unidos, which is not registered and worked “clandestinely” for fear of possible reprisals against its members.70

The example from Chile in Box 9 described the successful establishment of a trade union. However, the establishment of new workers’ organizations in the platform economy faces several challenges, including a high membership volatility due to the often temporary nature of this type of work and the registration processes for public recognition as a trade union (Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas 2018).71 Box 10 describes the attempt to form a trade union for platform workers in Ukraine and describes the related obstacles that are common in many countries around the world.

Box 10: Challenges for creating a trade union for platform workers in Ukraine

In Ukraine, 72 after workers’ protests (predominantly from Glovo, UberEats and Dominos Pizza) about 30 riders decided to create a union called the Independent Couriers Union. They adopted a charter, but the organization was not approved by the state registration process. Eventually, because of the high turnover among platform workers, courier-members of the union quit their job and ceased union activities.

Establishment of works councils in the platform economy

In some countries, workers in the platform economy have started to create works councils. Depending on the country, works councils may enjoy a wide variety of rights, from information, consultation and participation to co-determination of rights. However, when establishing a works council platform workers are reported to sometimes face obstacles related to the measures taken by platform companies, while the temporary character of platform work may reduce incentives for workers to engage.73 Box 11 illustrates the election of works councils and health and safety representatives in location-based platform companies in Australia, Austria, Germany and Norway and the establishment of the Riders Forum in Belgium.

Box 11: Establishment of works councils and health and safety representatives

-

In Australia, 74 unions organizing food delivery riders utilize the provisions of work health and safety (WHS) legislation to obtain the election of worker representatives. The WHS Act sets down a process for worker health and safety representatives to be elected by “workers” in a “work group”. In early 2021, seven Deliveroo safety representatives were elected – an event heralded by the union as “a milestone for the platform economy in Australia” as it would enable riders to help co-workers enforce their rights and counter safety risks such as accidents, falls and heat stress.75 The elected representatives have important powers under the WHS Act, including to investigate safety risks and worker complaints in relation to safety issues, to direct that unsafe work cease, to notify SafeWork New South Wales of safety incidents and to initiate the process for forming workplace health and safety committees.

-

In Austria, the Transport and Services Union (VIDA) established a works council for Foodora cyclists. Among the objectives of the works council are better working conditions, additional premiums for work at night or in winter and permanent employment contracts for riders.76

-

In Belgium, the platform company Deliveroo announced the creation of the Riders Forum, which will meet every three months and is supposed to be used for consultation and discussion between management and representatives of delivery riders. The company announced that 20 Belgian couriers will be elected and act as spokespersons for the 3,000 couriers who work for Deliveroo in the country. However, they will not constitute a traditional works council. Therefore, the to-be-elected spokespersons of the delivery drivers will not enjoy the same protections against dismissal as union representatives.77

-

In Germany, riders for the platform company Lieferando (Just Eat Takeaway.com) established works councils in Cologne, Stuttgart, Nurnberg and Frankfurt/Offenbach and a works council responsible for Kiel, Hamburg, Hanover and Braunschweig.78 However, news articles in the media report about obstructions of works council elections from the side of the company in some instances.79

-

In 2018, an agreement was signed to establish a European Work Council at the platform company Delivery Hero, including a provision to include employee representatives on the supervisory board

(IOE 2019) . The agreement was signed with the Food, Beverages and Catering Union, the Italian Federation of Workers of Commerce, Hotels, Canteens and Services and the European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism. In 2021, the grocery delivery platform Gorillaz appealed to labour courts to stop the election of a works council in Berlin. However, a labour court ruled that workers may go forward with the election of a works council.80

-

In Norway, the food delivery platform Foodora and the trade union Fellesforbundet have signed a collective agreement (see Ch. 3). The collective agreement sets the framework for setting up shop stewards in the company. The shop stewards’ working committee holds monthly meetings with the management, at which matters are raised by both parties. Foodora has a duty to inform workers about upcoming changes and to listen to the views of the shop stewards.81

Initiatives on online web-based platforms in the platform economy

In comparison to the situation in the location-based platforms, the legal and practical obstacles to organize and establish formal workers’ organizations are even more pronounced for workers on online web-based labour platforms that span different jurisdictions (ILO 2021a). These workers may also be less willing to organize. This observation was confirmed by the present study, which finds that groups of workers on online web-based labour platforms often take the form of online groups in which workers discuss their tasks and grievances. One example are groups of microtask workers on Amazon MechnicalTurk

Box 12 illustrates initiatives on online web-based labour platforms that address content creators on platforms such as YouTube, Twitch or Instagram and workers on platforms such as Mechanical Turk, Upwork or Clickworker. In addition, it provides a good example of how protests against the adoption of a new law translated into in-person demonstrations by IT workers and online web-based platform workers in Ukraine.

Box 12: Initiatives on online web-based platforms

-

The YouTubers Union is an association of YouTubers and was founded in 2018. The aim of the YouTubers Union is to improve working conditions of video creators on YouTube.82 Since July 2019, the YouTubers Union has been cooperating with the German trade union IG Metall in the “FairTube” project. Their demands include, among other things, clear and comprehensible rules for advertising and deletions of videos, the establishment of an independent arbitration body, and the establishment of a co-determination body for YouTubers vis-à-vis the Group. The FairTube project addresses content creators who share their content on a platform such as YouTube, Twitch or Instagram and workers who do work on platforms like Mechanical Turk, Upwork or Clickworker, as well as workers who complete tasks in the physical world, such as mystery shopping83 and promotion checks.84

-

In Ukraine, associations of online web-based platform workers are generally formed through chats on Telegram or in groups on social networks. In 2021, a group of about 300 IT workers created the first independent association in the IT sector in Ukraine, the IT Guild Ukraine,85 in protest against the Law of Ukraine on Stimulating the Development of the Digital Economy in Ukraine. The IT Guild Ukraine represents both platform workers and staff of IT companies.86 In July 2021, they organized protests in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Dnipro against the adoption of the above-mentioned law.87 The Facebook group “beFree – freelance for Ukrainians on Facebook”88 has almost 32,000 members. It unites freelances, including those working on web platforms. Participants share experience in performing tasks on various web platforms, provide advice on registration as entrepreneurs and pay taxes, and have the opportunity to get advice from accountants, lawyers and others.

-

In Spain, the trade union UGT promotes a network of creators and influencers to demand decent working conditions from digital platforms – such as YouTube, Instagram and Tik Tok. The digital workers associated with UGT denounce “the lack of transparency and protection of creators and consumers against arbitrary algorithms …”.89

Organizing migrant workers in the platform economy

In several countries, labour platforms are an important source of employment and income for migrant workers. It is estimated that about 17 per cent of platform workers are migrants and that proportion is higher in developed countries (38 per cent) than in developing countries (7 per cent) (ILO 2022a).

For example, in Argentina migrants represent about 74 per cent of the workers surveyed in the delivery sector

-

“In contrast to non-migrants, migrant drivers are more likely to rely on the income from Uber to support themselves and their families. More importantly, these migrant drivers appear to have fewer alternative work options available to them, and thus find themselves more precariously positioned, and reliant on the Uber platform and its flawed star-rating managerial system. ‘Flexible’ working hours allow these precarious migrants to accrue enough work to make the money necessary to survive, whereas more secure workers – who are often non-migrants – can access flexible shifts when it is convenient for them to do so”

(Holtum et al. 2021, p. 16) .91

A high share of migrant workers can constitute another hurdle for the successful unionization of workers in the platform economy. This may be due to language barriers, the temporary character of the work relationship or unclear immigrations status. Box 13 illustrates with concrete examples the challenges identified and how trade unions reached out to migrant workers in the platform economy.

Box 13: Workers’ organizations and migrant workers

-

In Australia, many of the union efforts in the platform economy have been undertaken on behalf of migrant workers (e.g., several of the TWU’s test cases and its advocacy in response to food delivery rider deaths in 2020). In addition, union campaigns and actions in the platform economy have been coordinated with the Migrant Workers Centre (MWC),92 which is located at Victorian Trades Hall Council in Melbourne. As part of its activism to counter migrant worker exploitation, the MWC has lobbied federal and state governments to enhance protections for platform workers, including the provision of work information in their own languages.93

-

In Chile, in Riders United Now was founded in 2020, mainly to organize PedidosYa workers. The majority of delivery drivers who identify themselves with Riders United Now are Venezuelan nationals and almost all of them are in a regular migratory situation.94

-

In Spain, migrants make up a large proportion of platform workers, in particular delivery workers: two out of three (64 per cent) riders come from Latin America

(Adigital 2020) . In interviews, trade union organizers expressed the view that the vulnerability of people without a work permit forces migrants to provide services without any guarantees regarding pay or working conditions. And this is also one of the difficulties when it comes to trade union action or affiliating riders.95 -

In Ukraine, among workers in the platform economy there is generally a low awareness of trade union activities and the fact that worker interests can be represented by organizations. This is particularly true of young workers, who are heavily represented on some labour platforms, as well as for migrant workers, who are often either unaware of their rights or do not speak the local language, or are only interested in working temporarily.96

Demonstrations, strikes and collective log-offs by workers in the platform economy

In recent years, the growth of the platform economy has increasingly been accompanied by coordinated group actions of platform workers, including wildcat strikes, collective log-offs and demonstrations. Chapter 1 found that about 8.9 per cent of app-based taxi workers and 3.4 per cent of app-based delivery workers reported in the surveys that they had participated in coordinated group actions such as a protest, memorial, demonstration or collectively logging out of the app, with notable differences between countries. A large share of coordinated group actions of platform workers aimed to achieve a pay increase. Some of the coordinated group actions also sought to achieve the recognition of union status for platform workers’ organizations (see Chapter 1).

Building on the general findings of Chapter 1, the following sections describe concrete examples of coordinated group actions in more detail by giving, for example, information on the organization of protests, the number of platform workers involved and their demands (see Box 15). Important findings from the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest97 are also summarized.

Findings from the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest

The Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest uses data drawn from a combination of online resources, including news media databases. It documents a general increase in the volume of protest events for the period January 2017 to July 2020 and reports the number of protest incidents related to working conditions on digital labour platforms (Bessa et al. 2022).98 It has been found that pay was by far the most prominent cause of dispute actions prior to the pandemic (64 per cent), followed by employment status (20 per cent), health and safety conditions (19 per cent) and regulatory issues (17 per cent). Protests about health and safety conditions have constituted more than half of the disputes since the pandemic started (up to 65 per cent of all protests in the second quarter of 2020), with Latin America being particularly affected. Grievances connected to union recognition motivated 6 per cent of all protests by platform workers worldwide. Labour protests on digital labour platforms are mostly driven by workers themselves and ad hoc constituted informal groups of workers, but increasingly protest actions receive support from newly established and already existing trade unions (see

Box 14: The involvement of trade unions in protests