Labour protests during the pandemic

The case of hospital and retail workers in 90 countries

Abstract

With a novel methodology searching news events from world’s largest news agencies via the online GDELT project, this report documents protest of key workers against their working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in 90 countries. The report offers the first global dataset of labour protests of key workers during the pandemic. It focusses on two sectors, healthcare and retail. The results show that, overall, despite large volumes of protest over acute COVID-related problems such as the provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), the main concern of protesting workers during the pandemic was their pay. Collective action accompanying demands for pay rises involved not only the withdrawal of labour, but also demonstrations and leverage tactics. Health and safety was the second most important concern, and protests linked to these demands did not cease when the pandemic became less deadly. Protest spiked during the initial March 2020 lockdowns, before continuing at a lower level throughout the pandemic. The report identifies important variation between countries and sectors, and highlights specific local contingencies, and strategic decisions taken by workers and their unions. To this end, the report also analyses in more detail five countries where protest was particularly important: France, India, Nigeria, the United States, and Argentina. The report offers a first step to understanding the variety of labour protests beyond more institutionalised forms of collective voice. It will be important to study further the relation between informal forms of protest action and institutionalised gains, during and beyond COVID-19.

Key findings

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the dependence of societies on a variety of key workers. This includes not only doctors and nurses, fire fighters and those working in public safety or transport but also those working in logistics, and retail and other key sectors. Essentially a large number of occupational groups have been, throughout the pandemic, risking their own safety to ensure that people had vital necessities.

Against this background, the working conditions of key workers have come to the fore during the pandemic. Facing an extremely challenging environment, key workers have raised their concerns about their working conditions through different forms of protest, including demonstrations, petitions, “sick outs”, public campaigning, or lobbying alongside conventional forms of strike action. The study examines protests by keyworkers in 90 countries, based on those with the highest number of COVID19 infections per inhabitant. In total, 3873 protest events of key workers in healthcare and 466 events in retail were identified during the first 15 months of the pandemic.

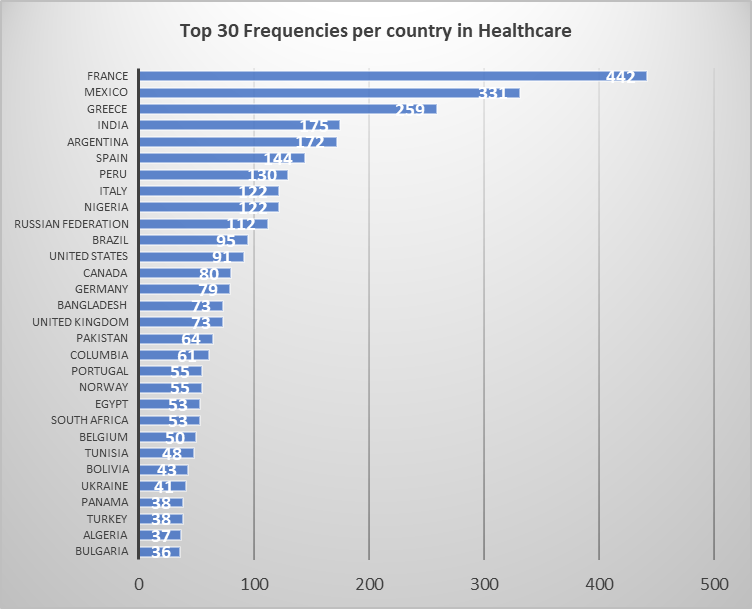

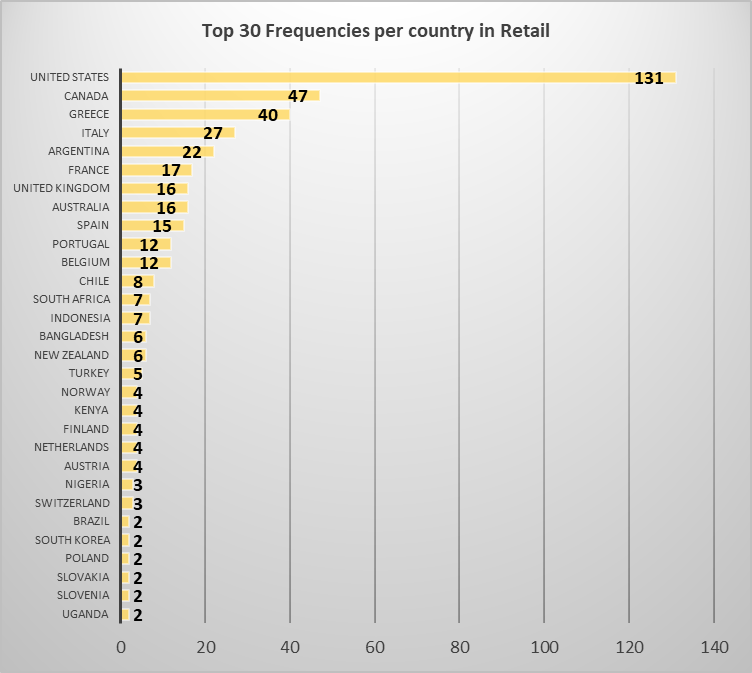

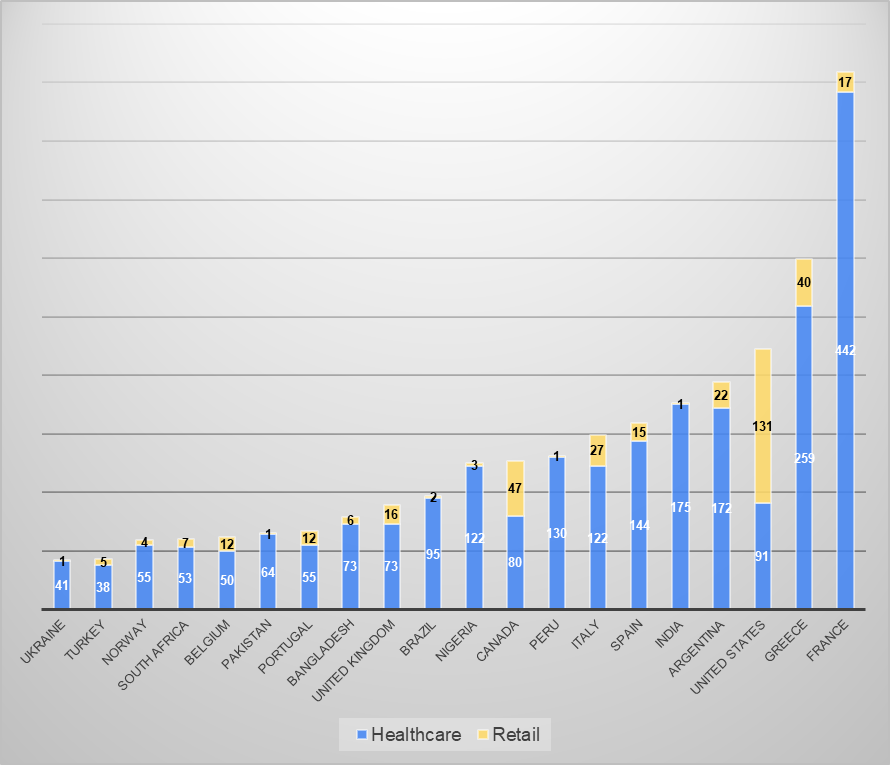

Protest spiked in the initial lockdowns of March 2020, but continued at a lower level through the rest of the time period. Protests in retail occurred most often in Europe and North America, while protests in healthcare were most common in Europe and South America. The highest number of protests overall occurred in France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Nigeria, the Russian Federation, India and the United States of America. Overall, protest was more frequent in healthcare than in retail, underlining higher levels of organisation in the healthcare workforce, and suggesting retail workers were relatively more likely to choose “exit” rather than “voice” when faced with worsening pandemic conditions. However, the data also reveal prominent protest movements by retail workers in certain countries, notably the United States and Argentina.

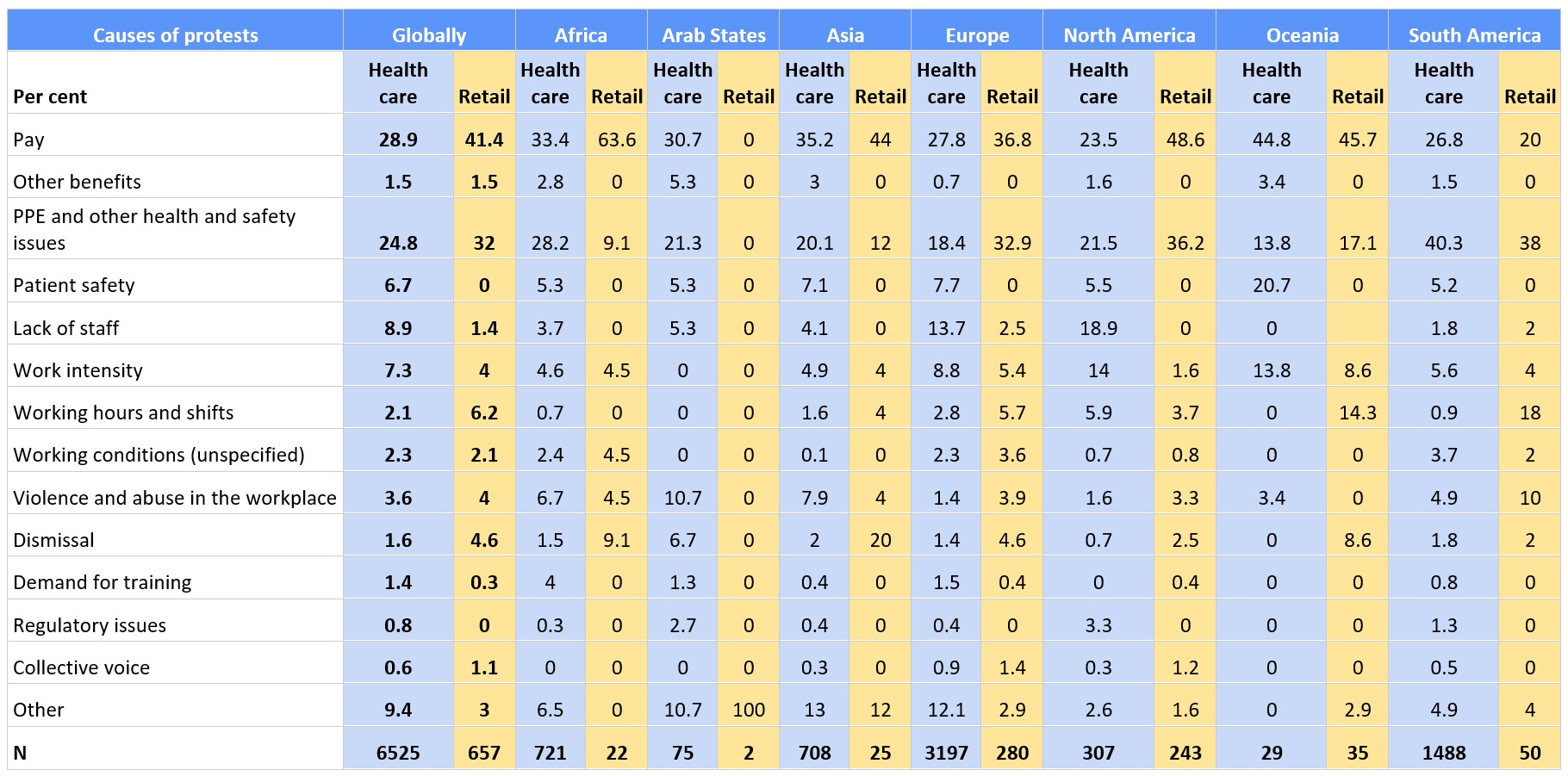

The evidence shows that, around the globe, key workers have protested for better pay and better PPE and raised concerns over working hours and work intensity, staff shortages, patient safety, violence and abuse in the workplace and dismissal. Pay was the most common trigger for protest globally, although regional differences were evident for other sources of grievance.

For healthcare workers, the lack of PPE and other health and safety measures were more often a trigger for protest in Africa and South America. Work intensity was disproportionately a trigger of protest in North America and Oceania. Patient safety was most often a cause for protest in Oceania. Abuse at the workplace was the most widespread trigger in the Arab States.

For retail workers, dismissal was the most common cause in Asia, where every fifth case of protest was related to cases of dismissal. Dismissal also accounted for a tenth of retail worker protest in Africa. Demands for collective voice or training were very low across both sectors and all countries.

Protests through strike action took place in just a fifth of cases in both sectors. The most frequent actions by key workers involved public demonstrations in the healthcare sector and leverage tactics in retail.

While we therefore saw important differences across countries and regions, we also detect important variation within countries, between sectors. Some countries experienced very high levels of protest in one sector and negligible levels in another. In explaining this variation, we suggest that strategic decisions by unions are likely to be important. For example, the disproportionately high volume of protest in French healthcare appears to result from a proactive decision by French unions to explicitly link acute COVID-related problems (such as PPE shortages) to a much more general concern of a perceived long-running worsening of conditions in the sector. By contrast, in healthcare in India a greater proportion of protest activity seemed to be conducted outside formal union channels, and tends to involve very short “flash strikes” in response to acute problems such as unpaid wages. In the United States, the disproportionately high level of protest in retail may be related to proactive campaigning by particular organisations.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a wide and deep impact on the world of work and has exerted huge pressures on workers in many sectors of employment. Occupations have been thrust into the public eye to an unprecedented extent, especially the various key workers who have kept vital services functioning even as large swathes of economic activity came to a standstill. These workers were found in many sectors, including health and social care, essential public services like fire brigades, public safety, and education, as well as transport, logistics, and frontline retail work. The pandemic underlined the importance not just of health workers but other occupational groups, like retail workers. These occupational groups had previously been overlooked or even denigrated in public discourse as “low-skilled”, precarious work with few prospects for advancement – but were now visibly risking their own safety to ensure that people still had vital necessities.

Many of these frontline jobs exposed workers to the dangers of COVID-19 transmission, in too many cases ending in tragic deaths. However, while the public view of the critical and essential role played by many occupational groups may have been challenged (for instance, with many new references to the “heroism” of frontline workers), even more important was the ability of key workers to influence their own working conditions. Given the new and unforeseen challenges of the pandemic for workers, and the speed and urgency of many changes, workers have had to experiment with new forms of interest representation and mechanisms of voice, with consequences that may endure beyond COVID-19.

It is therefore important to understand the variety of forms of voice were used by key workers during the pandemic to express and advance their demands. What measures have key workers taken to improve their working conditions in the context of devastating COVID-19 transmission, and unprecedented new pressures exerted on them? In practice, we find that, alongside conventional trade union activity, more ad hoc forms of voice – which we might label protest – have been vital means for workers to represent their own interests in formidably difficult circumstances.

Historically, worker voice was institutionalised through union membership and collective bargaining. As a last resort, disruption via strikes served as an important power resource for workers. The speed and unforeseen nature of change in the pandemic resulted in other forms of protest, often outside these institutional channels. Indeed, many groups of key workers already worked in contexts where, long predating the pandemic, insecure work was common and institutionalised collective bargaining typically very weak – such as retail. Institutional forms of voice are severely limited in such settings, but this does not mean workers have no recourse. Consequently, the paper examines protest by key workers: that is, a more diffuse range of activities, undertaken by workers and designed to mobilise support for their demands, including demonstrations, petitions, “sick outs”, public campaigning, or lobbying, alongside more conventional methods like strike action.

The first case of COVID-19 was detected in China, which was also the first country to announce a lockdown on January 26th, 2020. New COVID-19 infections were already detected in other countries in January 2020, but most other countries began lockdowns only in March 2020. We therefore begin our analysis of worker protest from March 2020 onwards. We analyse protest by workers in healthcare and retail; two sectors where workers were required to continue attending work, but which contrast sharply in other ways. Much healthcare work has long featured a comparatively vaunted status in public discourse around the social value of work, often involves relatively defined career paths and qualification requirements, and in many cases is more likely to involve union representation and collective bargaining. By contrast, retail work has often been stigmatised as “low-skilled”, with weak security and weak prospects for promotion and career progression and is often perceived as particularly difficult to organise. However, during the pandemic, aspects of these stereotypes were profoundly challenged. Furthermore, these sectors were also selected for conceptual and pragmatic reasons explained below. Through a systematic analysis of worldwide news reporting, we charted thousands of instances of worker protest from across the globe during this time period and in these two sectors. We asked what the causes of these protests were, how they were manifested, and through which actors, and how they were distributed geographically. Overall, we found a great number of protests, with far more in healthcare than in retail. While there were protests in almost all the countries we examined, there was a notable concentration of protest events in a small number of countries, with protests most prevalent in France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Nigeria, Russia, India and the United States. There was also wide variation between sectors within countries; leading us to suggest that particular industrial settings and contingencies, and strategic decisions by key actors, played a more important role in catalysing protest during the pandemic than factors related to national-institutional context.

In what follows, we first review existing literature on the pandemic’s challenges for workers, with a particular focus on our chosen sectors. After a discussion of our research methods, we present our quantitative findings about the extent and nature of worker protest in the two sectors since March 2020. Before concluding, we consider key cases where protest was especially common; specifically in healthcare in France, India and Nigeria, and in retail in the United States and Argentina.

Literature review

1.1 The pandemic and work in retail and healthcare

The direct and indirect consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound effect on working life, and have posed particular challenges for many key workers, for whom options such as working from home have been impossible. While some of these workers have long been identified as critical public servants – notably, healthcare workers – this is less the case with other vital front-line jobs – such as supermarket retail. Challenges faced by workers in these and comparable industries during the pandemic include work intensification, substantial new health and safety hazards, and the psychological consequences of continuing to work in in fraught public-facing roles during a major public health crisis.

Before turning to our empirical investigation, we review existing research which addresses the employment challenges of COVID-19 – with particular focus on retail and healthcare – identifying issues for which worker protest is one potential response. We also consider from a more theoretical perspective how we might expect workers to respond to these issues, including the under-researched topic of worker protest. Comments from the ILO’s supervisory system for the year 2020 provide important context on our two sectors.1 In both retail and healthcare, the ILO noted problems of occupational segregation and pay gaps in many countries. Indeed, while gender discrimination does not feature in our quantitative findings as an explicit cause of protest, issues of gender inequality form vital context for much protest activity in these sectors; as the qualitative vignettes presented below make clear. Retail has also been subject to commentary about child labour in some countries though these issues did not appear to feature as important causes of protest in our dataset. In healthcare, through the supervision of the implementation of the Nursing Personnel Convention, 1977 (No. 177) the ILO has sought to catalyse the development of training, resourcing, and social dialogue standards for specific groups of healthcare workers in numerous countries. It also specifically noted the deficiency of PPE provision for healthcare workers in specific countries.2 This last issue, as we shall see, is a widespread problem which has motivated a large volume of protest in both retail and healthcare.

1.2 Retail

Retail work has long presented significant challenges from the perspective of workers’ rights and representation. In many countries, retail work remains weakly unionised, and dominated by extremely large employers who often have a track record of opposing union recognition (of which US giants such as Wal-Mart are emblematic: Lichtenstein, 2016; Hocquelet, 2016). Retail work is typically low-paid, with few opportunities for career advancement (McKie et al, 2009; Winton, 2021), and is often precarious, with weak institutional worker voice (Bailey et al, 2015; Mrozowicki et al, 2018). It is also a relatively feminised workforce (Brydges and Hanlon, 2020). In this context, pressures of the pandemic have greatly amplified already-formidable problems facing workers, including their gendered effects.

In understanding the effects of the pandemic on retail work we must start by acknowledging variation within the sector. Some types of retail work were considered critical or essential by most governments and continued to operate during successive lockdowns (most obviously supermarket food retail) and others were not (such as luxury goods). The picture in retail is therefore uneven. Overall, the retail industry was highly vulnerable to job loss due to lockdowns (Lemieux et al, 2020; Qian and Fuller, 2020). Indeed, a large part of the highly gendered employment effects of lockdown globally stems from the fact that job losses were concentrated in comparatively feminised work forces including sections of retail (Lee et al, 2021; Albanesi and Kim, 2021; Alon et al, 2021; Rivera and Castro, 2021). However, there were also spikes in demand for labour in critical retail operations (such as food retail), driven even higher by limits on mobility which reduced the availability of migrant workers (Burgos and Ivanov, 2021). Before 2020 there had been a long running trend in food consumption patterns, which had been shifting away from supermarket retail and towards restaurant and take-away businesses, but lockdowns sent this process into reverse overnight (Goddard et al, 2020; see also Leone et al, 2020; Burgos and Ivanov, 2021) while exerting new demands on grocery and cooked meal delivery services. Nevertheless, rising demand for labour in food retail should not be overstated or taken for granted, since it must be counterbalanced with trends towards automation that have also been accelerated during the pandemic (Lemieux et al, 2020; Albanesi and Kim, 2021).

In this context, particularly in supermarkets, retail workers who retained their jobs found themselves positioned as vital service providers on the front-line of public health battles. Major retail workplaces became prominent sites of COVID-19 transmission, and consequently became targets of new health and safety measures in many countries (Shahbaz et al, 2020; Goddard et al, 2020). Policymakers and businesses to some degree recognised that new training interventions would be necessary to enable retail workers to meet the demands of new pandemic-prevention measures (Sulaiman et al, 2020). However, this imperative clashed with the pre-pandemic context. Evidence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland suggests that the long-standing weakness of training and career pathways in many retail operations meant this pandemic-driven prospect of upskilling was often a false promise (Winton, 2021). Moreover, in many countries retail employers and governments have failed to provide adequate new protections for workers, for instance in terms of personal protective equipment (PPE) or strengthened rights to sick leave- though of course retail is by no means unique in this respect (De Matteis, 2021).

As such, retail workers faced severe pressures greatly increasing the stress and difficulty of their work, stemming from multiple sources: danger of infection, difficult relations with customers and a lack of meaningful power – often taking on new safety-related rule enforcement responsibilities, but without influence in shaping the nature of those rules, or any corresponding career progression (Elnahla and Neilson, 2021). Voorhees et al (2020) characterise pandemic-era frontline service industry workers, including in retail, as a neglected and overlooked group, facing anxiety and burnout, abusive customers, and unprecedented new demands for health and safety issues with often inadequate training provision. Evidence from Italy underlines that retail workers were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 transmission due to their proximity to large volumes of customers (Barbieri et al, 2021). In the pandemic, women in retail work were more pessimistic about their futures than men, evidence from Spain suggests (Rubio-Valdehita et al, 2021).

However, the pandemic may also have prompted more empowering change for retail workers. As Mejia et al (2021) argue, the public narrative around retail shifted rapidly. While retail work had previously been denigrated in public discourse as low-skilled and low-paid, COVID-19 saw retail workers re-imagined as “heroes”. The social importance of their work became more prominent and indisputable, while the responsibilities and pressures placed on them mounted up. It is too early to say whether this discursive and ideological shift will endure in years to come. Nonetheless, when combined with increased demand for labour in food retail (though not across retail as a whole), we may surely ask: are we likely to see a more assertive retail workforce in the wake of COVID-19, which is more conscious of its own value, and if so, how may this be manifested?

It is too early to answer these questions definitively, though our data presented below provide an initial understanding. Classic tensions between “voice”, “loyalty”, and “exit” are relevant here. Where retail workers’ expectations and demands are raised and then disappointed, one likely response may be to leave the sector to seek employment where conditions are better. While there is limited pandemic-era evidence on turnover rates specifically in retail, studies of comparable occupations such as restaurant work (De Souza Meira, 2020) and hotel employees (Jung et al, 2021) suggest an uptick in voluntary quits.

The relative weakness of union representation, and high levels of casualisation, in retail may lead us to expect “voice” (including forms of protest) to be less common than “exit” (turnover) as a response to poor working conditions. At present, data does not exist that enables us to gauge and compare the relative frequencies of these phenomena. While some studies find evidence of a new propensity to protest among retail workers during the pandemic, these focus on identifying particular cases rather than evaluating wider global trends. In a somewhat polemical piece, Orleck (2020) describes protest actions by retail workers in the United States during the pandemic. What is notable in Orleck’s account is the variety of problems addressed through protest. Archetypal COVID-19 problems including PPE provision and demands for better social protection feature prominently as causes of protest, but so do concerns such as pay. It is possible that workers are capitalising on a strengthened sense of their own value to demand improved conditions, rather than simply responding defensively to acute and urgent deficits in health and safety procedures. Moreover, labour protest could be manifested through “traditional” means such as trade union organising and strikes but is not necessarily limited to this. The concentrated power of employers in retail makes this risky, however, and evidence is emerging of protest organisers in US retail being targeted for reprisals (Mejia et al, 2021:7). Thus, while the pandemic may have catalysed potentially important changes in retail worker interest representation, existing research does not enable us to say for certain, since there is so far no systematic data setting pandemic-era protest in a global perspective.

1.3 Health care work

Health care work has some similarities with retail in the pandemic, since it is another sector in which frontline workers were placed at risk while providing vital services. However, the industrial context is very different. The problems of insecure work are not as prevalent as in retail, and in many countries institutional voice is stronger. Healthcare work often requires more specific training or skills requirements than retail and has more clearly-structured career pathways. On this basis, we may anticipate healthcare workers are more likely than retail workers to exercise voice rather than exit in response to problems they face at work.

Nonetheless, in the period prior to the pandemic, healthcare workers were facing significant industrial relations challenges in many countries. Often, these were linked to budget pressures which reduced pay and staffing rates, potentially leading to work intensification, alongside shifts towards increased market competition in many healthcare systems (Krachler et al, 2021). The latter may carry consequences for workers’ material conditions as well as the risk of hospital closures and may also lead to qualitative shifts in the nature of healthcare work that conflict with workers’ own conceptions of how to do their jobs (Greer and Umney, 2022). Hence, while healthcare workers may historically have been relatively unlikely to strike and protest over working conditions, evidence from some countries suggests this has been changing over the last decade, including in France and the United Kingdom (Umney and Coderre-LaPalme, 2017), and Germany (Greer, 2008).

The pandemic has greatly intensified problems facing healthcare staff at work. Most obvious were concerns about safety, as poignantly underlined in Treston’s (2021) personal reflection on life as a nurse during the pandemic. Infection is a serious risk facing hospital workers, and evidence from Italy suggests the most common source of infection was not patients but other healthcare workers (Mandic-Rajcevic et al, 2020). As with retail staff (and many other essential workers), risk of infection was exacerbated by deficiencies in PPE provision; powerfully underlined by the experience in the United States (Razzak et al, 2020). Long hours, intense work and isolated living conditions became a more prominent problem for healthcare workers, as evidence from China shows (Cao et al, 2020). Healthcare workers’ safety is of course vital, but they also need a voice in establishing how changes to their workplaces are managed, to ensure wellbeing is front-and-centre (Dennerlein et al, 2020). In the pandemic this has often been lacking.

Aside from the risk of infection, the pandemic also imposed psychological strains on health workers, which are widely documented across many countries (Wanigasooriya et al, 2021; Romero et al, 2020; Mattila et al, 2021). Evidence from Spain suggests that this includes a rising prevalence of suicidal thoughts (Mortier et al, 2021). Evidence from China suggests the fear of infection was a source of stress among healthcare workers, particularly frontline nursing staff (Wang et al, 2020). Incidences of stress, depression and anxiety among healthcare workers appear to vary internationally, for instance being identified as proportionately a more severe problem in Italy (Lasalvia, 2021) than in China (Wang et al, 2020). As in retail, the effects of this strain were gendered. Research in Egypt found women were more likely to experience negative psychological effects than male counterparts (Elkholy et al, 2021), as did research from Chongqing (Xiaoming et al, 2020).

The literature therefore offers much evidence of the strains faced by healthcare staff during the pandemic. However, there has been much less focus on how they responded to this. Historically, there is evidence that healthcare workers are often reluctant to contest the terms of work, owing to their valuing of their caregiving role; though some researchers question whether this was already changing in the years immediately before COVID-19, owing to restructuring and marketisation in healthcare (Umney and Coderre-LaPalme, 2017). As with retail, we can distinguish between evidence which underlines the dangers of healthcare staff exiting their jobs in response to these problems (e.g., Jang et al, 2021), versus literature emphasising ‘voice’ in the form of protest. The latter is highly scattered and limited to case studies of particular protests – including a number of studies from Mexico (Torres-Hernandez et al, 2021; Navarro and Santillan, 2020) – with seemingly no quantitative data to-date.

1.4 Worker protest in the pandemic

Reviewing pandemic-era literature on retail and healthcare raises some important questions. Most prominently: how would workers respond to the challenges they faced? While literature is emerging which underlines turnover (or turnover intention), there is much less examination of cases where workers contested the terms of work (i.e., exercising voice rather than exit). Have workers been contesting the terms of work during the pandemic, and if so, how? Relatedly, while many of the problems we have identified appear across many countries, we also need to recognise the possibility of wide variation between countries: not only because of a long-standing comparative literature emphasising how different institutional contexts condition patterns of industrial relations (e.g., Hall and Soskice, 2001; Lansbury et al, 2020), but also because of the uneven impact of the pandemic itself. Thus, while it is common to find studies emphasising the disproportionate loss of women’s jobs, this effect is not universal and may be very different depending on national conditions (Ikkaracan and Memis, 2021; Reichelt et al, 2021). More generally, countries with more flexibilised labour markets appear to have been those where employment effects of COVID-19 were most severe, suggesting the crisis is highly nationally-patterned and is exacerbating inequalities in countries with already weak labour protections (Fana et al, 2020).

Hence a global perspective on the extent of labour protest in these sectors, which seeks to identify national variation, is an important unanswered empirical question. The literature surveyed so far underlines the prominence of a particular set of concerns which have been greatly amplified by the pandemic: including, health and safety concerns; new pandemic-prevention responsibilities, often without adequate support or training; and severe work intensification. Moreover, while we have cited evidence of workers protesting over these issues, we also noted that issues such as pay have featured in pandemic-era protest. Hence while it may be true that essential workers are to some extent victims of neglectful governments and employers (De Matteis, 2021) and are responding through protest to acute life-threatening health and safety problems, they may also be asserting demands for more progress on “bread-and-butter” issues like pay. Yet, no studies to date systematically investigate the causes and triggers of labour protest during COVID-19.

As well as the causes or triggers of protest, there is a need for a better understanding of the forms protest takes. Industrial relations scholarship has tended to focus on institutional functions such as collective bargaining and within that context, the use of strikes to advance demands at the bargaining table. For the purposes of this paper, however, we focus on “protest”; a broader and more diffuse term referring to any collective action launched by workers, designed to mobilise support for their claims. This category would certainly include strikes, but also includes demonstrations, boycotts, social media campaigning, and other methods. Furthermore, while established trade unions may be vital in launching protest initiatives, protest may be much more informal than the actors typically involved in institutional industrial relations; including workers cooperatives, new insurgent trade unions, and entirely informal groups of workers without any formalised organisational structure at all.

This broader conceptualisation of protest, while rarely examined systematically in industrial relations literature, is likely to be important in the pandemic context, for several reasons. First, the pandemic has imposed sudden and intense pressures in contexts where, in many countries, trade unions have a weak presence, creating new grounds for contestation where opportunities for institutional voice are limited. Second, where workers have a deep awareness of their importance as critical workers in a public health emergency, there may be great affective and normative barriers to taking strike action, necessitating other methods of protest. Third, social distancing measures make typical strike practices such as picketing more problematic, which may lead in turn to innovation. So, we expect protest activities among retail and healthcare workers to exhibit a diverse set of practices during pandemic conditions.

The significance of other forms of protest are not simply a consequence of the pandemic, however. Some forms of protest may be becoming more important in industrial relations as established institutional voice mechanisms decline. Some trade unions, for instance, have adopted more protest-oriented approaches in some countries, reconfiguring themselves as social movements. This may be driven by both the decline in established institutional power resources, as well as a genuine desire to influence a wider policy agenda by shifts towards “social movement unionism”. There is some evidence of this already in the hospital sector. Greer’s (2008) study of the hospital system in Hamburg, for instance, shows unions moving towards more social movement-oriented tactics as institutional resources are closed off.

Consequently, we also draw on insights from social movement research. As Della Porta and Diani (2015: 3) explain, “social movement studies […] stand apart as a field because of their attention to the practices through which actors express their stances in a broad range of social and political conflicts”. A key strength of social movement research is its commitment to understanding changing forms of protest – that is, shifts in the way that grievances are expressed (ibid.; Alimi 2015; Millward and Takhar 2019; Tarrow 2015; Wang and Sole 2012). By contrast, industrial relations research has tended to apply standardised measures across different historical and institutional settings: measures such as official strike data, union membership, collective bargaining coverage, and so on. While this approach brings benefits in terms of consistency and comparability, it also carries disadvantages, which become especially clear when trying to understand forms of worker contestation that fall outside these conventional, institutional forms. Nevertheless, there clearly are many examples of work stoppages by key workers, and it is therefore important to try and develop methods for capturing the broad range of protest events. Social movement research thus provides vital insights, drawing attention to the need to understand workers’ protest not just work stoppages related to collective bargaining, but a wider multiplicity of protests, sometimes of the most informal kinds. Moreover, it encourages us to think about the dovetailing between formal and informal activities, including where trade unions support, or draw support from, broader protest movements.

Methodology

This report draws on a newly created dataset documenting incidents of labour protest by key workers globally. Data were gathered via the online GDELT project, which monitors worldwide news reports, translating online articles in over 100 languages, with a news search interface. GDELT collects reports from the world’s largest news agencies combined with the Google News algorithm. We searched for protest in 90 countries, choosing those countries where rates of COVID19 infection were highest (cases per 100.000 inhabitants). We also included some countries with lower rates of COVID19 cases, but which were of interest.

We defined healthcare and retail quite flexibly, but the nature of available online resources meant that we had to adopt more narrow search strategies, in order to reduce the generation of irrelevant results. We therefore focussed on workplaces as occupation as a way of finding relevant news coverage of worker protests. In retail, we were concerned to find cases of protest by key retail workers – rather than retail not deemed critical – and therefore focused our searches on supermarkets and other food and grocery shops in the formal economy, as well as grocery delivery. Furthermore, while recognising that in many countries retail is more often organised within the informal economy – with high levels of self-employment and family labour – our concern to examine collective action among employees (whether or not legally defined as such) guided our strategy towards more formalised sectors. To do this, we identified the five biggest supermarket chains in each country investigated, to identify labour protests in or around them. We included the largest online retail company, given the prominence of this one company’s services during the pandemic. For the healthcare sector, which is generally more formalised, we searched using workplaces and occupations, as described below. Although our searches included the term hospital, in practice this strategy also identified protests by workers in other healthcare settings. Due to the nature of the COVID19 health crisis, though, it does appear that worker protest was concentrated significantly in the hospital sector.

As a result of these considerations, our strategy for searching online resources for reports of worker protests in healthcare and retail was as follows. For the healthcare sector, we used relevant sector-specific keywords, including hospital, plus occupational groups, including nurses, doctors, health workers, and cleaners, and added protest-related search terms including strike, demonstration, rally, march, stoppage, unrest, dispute and conflict. For the retail sector we identified the five largest supermarket chains in each country and searched for their names, as well as more general descriptions of workplaces in retail like supermarket, store, retail, shopkeeper, food shop, and grocery store, combined with keywords such as protest, strike, stoppage, rally, mobilisation, fight, dispute, and demonstration. We carried out these searches for each of the 90 countries selected.

Through this systematic search of the GDELT database we initially identified almost 100,000 news articles. These articles were then needed sifted manually to identify those related to worker protest because some included protest and healthcare search terms but in a different context – for example an article about a protester injured on an unrelated demonstration and taken into hospital could appear in the search results but was clearly not relevant to our current purpose. We thus selected only articles that clearly dealt with worker protest in critical retail and healthcare services.

Protest reports identified by this process were then coded manually through careful reading of all reportage. We coded for the type of protest action/type of labour protest, and the causes of labour protest. Codes were pre-defined. To ensure intercoder and intracoder reliability, coding rules were formulated. An initial codebook and set of instructions were subjected to rounds of reliability tests. In many cases, multiple news sources related to one event (requiring manual analysis to identify where different stories described the same event), which allowed us to discern overall protest dynamics (Hutter, 2014:5), mitigating bias in individual sources.

Table

|

Type of Action |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Strike |

Workers withdraw labour (sometimes publicly visible, sometimes not) |

|

Strike announcement |

Workers are letting the public, the employer and/or the authorities know that they are planning to strike at some point in the future |

|

Demonstration |

Workers visible in the streets or in front of the workplace, holding signs with demands, and not officially striking |

|

Leverage tactics |

Demands and complaints released in public, mainly in written form, with the intent of applying pressure towards employer and/or authorities, as a collective initiative of a group of workers, not a single worker. |

Table

|

Causes |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

PPE and other health and safety issues |

All issues concerning work-related injuries and diseases; physical injuries or psychological (work-related stress); physical or verbal abuse, threats or assaults against workers; preventive measures, including equipment or lack thereof; health insurance; loss of earnings while sick; training around health and safety issues; measures for dealing with emergencies, including fire. |

|

Pay |

Everything to do with worker remuneration, including demands for higher pay; protests at falling pay; unfair deductions from pay; irregular pay; non-payment (wages theft); bonus payments (including non-payment or withdrawal of bonuses); protests about level of commission deducted by gig economy platforms. |

|

Working hours and shifts |

Everything related to how long workers work each day and/or week; work breaks and rest periods; organization of working time across the day and week. |

|

Work intensity |

Everything related to workload and work effort; mental and physical exertion at work; tiredness and exhaustion (this may also relate to working hours or health and safety); excessive juggling of conflicting demands. |

|

Violence and abuse at work |

Workers are subjected to violence in the workplace or are physically or psychologically abused in any other way while working. |

|

Patient safety |

Workers protesting because they perceive the welfare of patients to be at risk given the resources available to them. |

|

Lack of staff |

All cases where workers demand more staff at their workplace. |

|

Unspecified working conditions |

Cases where the news article does not further specify the trigger of the protest. |

|

Demand for training |

All cases where workers demand more training opportunities from the employer. |

|

Dismissals |

All cases where the dismissal of workers is the reason for the protest (either protest by dismissed workers, or workers protesting for the reinstatement of co-workers). |

|

Collective voice |

All cases where workers are protesting for their right to organise |

|

Other Benefits |

All demands for benefits apart from pay |

|

Regulatory Issues |

Demands made on regulatory authorities (government, local, national) Examples include: nurses demanding to be incorporated into health professionals law; demands for inclusion in labour law; demands for other new legislation; demands for repeal of laws; demands to be recognised as medical professionals; residence regulations; demands for the implementation of agreements (if not covered by the above). |

Findings

Our key overall finding is the volume of protests. During the period of the pandemic we investigated, across the 90 countries studied, we observed 3873 protest events in the healthcare sector and 466 events in retail. This unevenness between the sectors – with far higher rates of worker protest in healthcare than in essential retail – tentatively supports our expectation, noted above, that healthcare workers may be more likely than retail workers to exercise voice rather than exit when confronted with problems at work. However, this picture requires further exploration and nuance, as we show in the qualitative vignettes set out below.

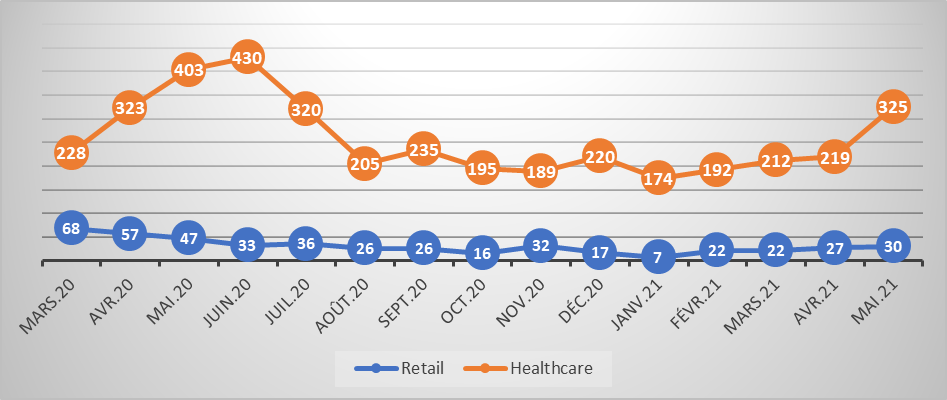

The level of worker protest also varied over time. There was a steadily high number of protests over time in the healthcare sector, with increases in May 2020 and May 2021, and a generally lower level in retail, with a peak at the start of the pandemic, with 68 protests in March 2020.

Graph

Source: Own presentation

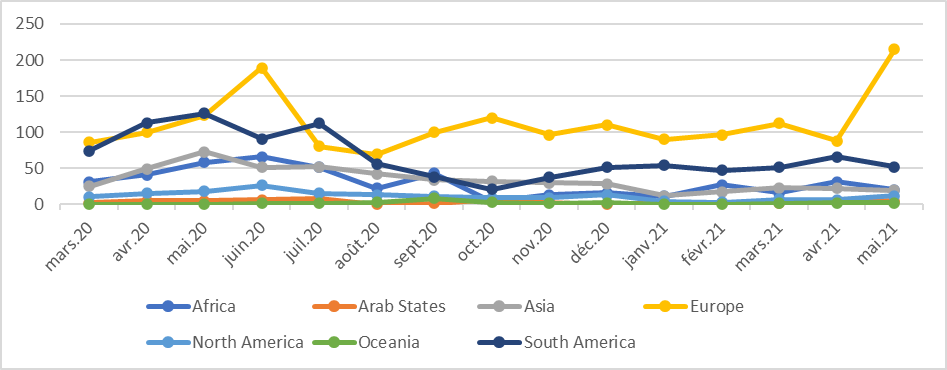

In most regions, protest was highest at the beginning of the pandemic and then decreased slightly, both in retail and healthcare. Interestingly, protest did not ebb away, but stayed steady and even increased in some regions and countries, as Graph 2 shows. In Europe, for instance, we see sustained levels of protest among healthcare workers, which increased to the highest level observed in May 2021, some 15 months into the pandemic. While our data do not enable us to explain this finding definitely, it suggests a persistence of worker grievances, and failure of employers and governments to properly address workers’ concerns. It may also point to an increasing confidence of workers to make claims against their employers – as we argue in relation to retail staff in the United States below.

Graph

Source: Own presentation

Overall, protest has not been equally distributed but concentrated in a smaller number of countries. In retail, many countries saw negligible levels of protest reported, and where there was protest, in most cases this amounted to fewer than ten incidents. Only 12 countries saw protest happening more frequently than this, with most of those in West and Southern European Countries (Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, United Kingdom), North America, Australia, and Argentina. Thus, 80 per cent of retail worker protest occurred in Europe and North America, with 50 per cent of events in just four countries the United States, Canada, Greece and Italy.

In the healthcare sector, again, protest levels were highest in Europe (43.3 per cent of the total), followed by South America (25.5 per cent). Elsewhere, France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Nigeria, Russia and India saw the highest number of protests, all with over 100 incidents each, and 50 per cent of protests occurring in just six countries: France, Greece, Spain, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and India.

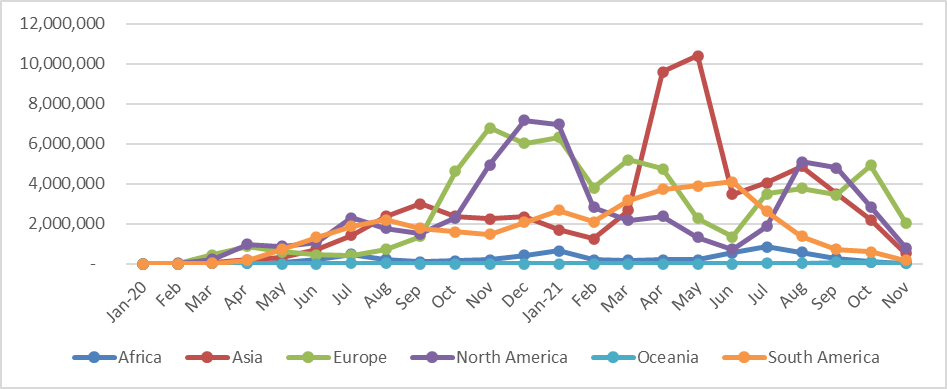

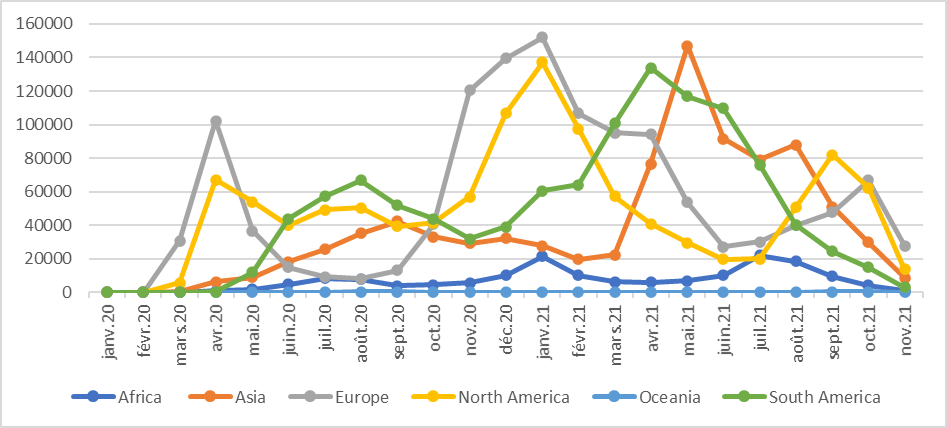

If we compare the frequency of protest events with the rise of COVID19 cases in these regions we see that worker protest spiked before the cases were high in those regions.

Graph

Source: Our World in Data; Own presentation

While all regions experienced a steady rise of infections from March 2020, with most saw a sharp increase of cases in November 2020, Africa had a lower rate of infection and no sharp increase in November 2020. However, in regard to protests in these regions, the rate of protest was higher before the pandemic reached its highest levels of infection. While further research would be beneficial, the highest levels of protests appear related to the first peak in number of COVID19 deaths in each region, particularly in Europe. March 2020 also saw the beginnings of initial lockdowns, which were themselves also driven by high death rates and hospitals being at or over capacity. Only China started its lockdown earlier, in January 2020.3

Graph

Source: Our World in Data; Own presentation

Graph

Source: Own presentation

Graph

Source: Own presentation

Table

|

Regions |

HC Frequency |

% |

Retail Frequency |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Europe |

1675 |

43.3 |

192 |

41.2 |

|

South America |

989 |

25.5 |

34 |

7.3 |

|

Asia |

508 |

13.1 |

20 |

4.3 |

|

Africa |

451 |

11.7 |

18 |

3.9 |

|

North America |

171 |

4.4 |

178 |

38.2 |

|

Arab States |

52 |

1.3 |

2 |

0.40 |

|

Oceania |

24 |

0.6 |

22 |

4.70 |

|

Total |

3870 |

100 |

466 |

100 |

For a substantial number of countries, however, we found negligible levels of worker protest reported in the data. In 46 countries we found no evidence of protest in retail, while in eight countries no protest was reported in healthcare. In six countries, no worker protest was reported for either of the two sectors: Dominican Republic, Denmark, Ethiopia, Montenegro, Singapore, and Togo.

3.1 Causes of protest

Protest events can occur for more than one reason (hence, the number of protests listed by cause is higher than the number of actual protest events). If we look at the causes of protest action, pay is the most common in both sectors, followed by PPE and related issues. In healthcare, 28.9 per cent of protests were stimulated by pay demands, and 41.4 per cent in retail. Concerns over PPE and other health and safety measures accounted for 24.5 per cent of all protests in healthcare, and 32 per cent of those in retail. Relatedly, in healthcare, concerns over staff and patient safety were causes for protests (8.9 per cent and 6.7 per cent respectively), which paints a concerning picture of the situation in hospitals during the pandemic. In many countries, healthcare prior to the pandemic had been going through periods of budget restraint and market-centred restructuring, reflecting a wider neoliberal policy trend in public service provision; which has in many cases involved pressures to limit expenditure on healthcare workforces and reduce capacity in healthcare systems (Klenk, 2016; André and Hermann, 2009; Krachler et al, 2021). These pre-existing pressures may have laid the groundwork for substantial waves of protest over staffing and resources during the pandemic – an argument we will develop further with reference to the French case study below. Nonetheless, the pre-eminence of pay as a concern in both sectors also requires note. It suggests that while issues of health and safety and resourcing assumed an obvious and urgent prominence, workers’ protest in the pandemic goes far beyond these acute problems.

In this context, work intensity and working hours were also high up the agenda for protest (7.3 per cent in healthcare, 4 per cent in retail for work intensity; 2.1 per cent in healthcare and 6.2 per cent in retail for working hours). Violence and abuse in the workplace led to protest in 4 per cent of cases: 236 in healthcare and in 256 in retail. Abuse was directed at workers from various sources, including patients, relatives of patients, police or authorities, management, colleagues, among others. In Nigeria, for example, doctors went on strike citing abuse from police on their way to work, stating: “We want to send a clear message to the police authority that they cannot continue to flout the presidential order on medical and health workers’ free access of movement to and from their places of work, and until the matter is adequately resolved, we remain on strike indefinitely.”4 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), pre-pandemic, up to 38 per cent of healthcare workers had already suffered physical violence at some point in their career.5 According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), in the first six months of the pandemic, 600 cases of violence were committed against healthcare workers.6 Our data show a broader range of grievances causing protests over abuse, from discontent with management, misconduct by superiors and colleagues – including bullying and harassment – abuse by patients and relatives, to more general grievances such as racism. Interestingly, some of the reasons for protest among those included in our “other” category express general protest over deteriorating economic conditions. In some countries with high numbers of protest events – such as Argentina – unions organised support structures for workers against deteriorating economic conditions, like soup kitchens (Ferrero 2020).

Table

|

Causes of protests |

Healthcare Frequency |

% |

Retail frequency |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pay |

1886 |

28.9 |

272 |

41.4 |

|

PPE and other health and safety issues |

1619 |

24.8 |

210 |

32 |

|

Lack of staff |

583 |

8.9 |

9 |

1.4 |

|

Work intensity |

478 |

7.3 |

26 |

4 |

|

Patient safety |

440 |

6.7 |

0 |

0 |

|

Violence and abuse in the workplace |

236 |

3.6 |

26 |

4 |

|

Working conditions, unspecified |

150 |

2.3 |

14 |

2.1 |

|

Working hours and shifts |

138 |

2.1 |

41 |

6.2 |

|

Dismissal |

105 |

1.6 |

30 |

4.6 |

|

Other benefits |

95 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

|

Demand for training |

94 |

1.4 |

2 |

0.3 |

|

Regulatory issues |

49 |

0.8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Collective voice |

38 |

0.6 |

7 |

1.1 |

|

Other |

614 |

9.4 |

20 |

3 |

|

Total |

6525 |

100 |

657 |

100 |

The dominant causes for protest varied across regions. For the healthcare sector, while pay was the most dominant reason for protest globally, the lack of PPE and other health and safety measures were more often a cause for protest in Africa and South America. Thus, 28.2 per cent of all protests in Africa were motivated by health and safety concerns, as were 40.3 per cent of protests in South America. Lack of staff was disproportionately likely to be a reason for protest in Europe and North America. This likely does not reflect lower rates of staffing in Europe and North America (since these countries tend to perform comparatively well on this metric according to OECD data7). Rather, it may instead reflect perceptions among staff of the longer-running degradation of work and reductions in capacity, as our commentary on the French case shows (below). Work intensity was disproportionately a cause of protest in North America and Oceania. Patient safety was more often than elsewhere a cause for protest in Oceania. Abuse at the workplace was a more widespread cause in the Arab States.

For the retail sector, pay (in 41.4 per cent of protest events) and PPE/health and safety (in 32 per cent of protest events) were also the most common causes of protest action, although with quite high regional differences. In Africa, pay was a cause in 63.6 per cent of retail worker protests, while in South America it accounted for only 20 per cent of the cases. As a cause of protests, PPE was slightly lower in Africa, Asia and Oceania but slightly higher in Europe, North America and South America. Working hours and shifts was a more common cause of protest action in South America (18 per cent) and Oceania (14.3 per cent) compared to the average of 6.2 per cent. Violence and abuse at work was slightly higher in South America (10 per cent) compared to the average (6.7 per cent). Dismissal was the most common cause of protest in Asia, where every fifth case of protest was caused by it. Dismissal also caused a tenth of retail worker protest in Africa.

Demands for collective voice or training caused few protests across both sectors and all countries. Regulatory issues did not account for many protest events and were often linked to pay where they did occur. For example, in Argentina, which had the highest number of protests stemming from regulatory issues, these were often linked to a law regulating the working and remuneration of healthcare workers.

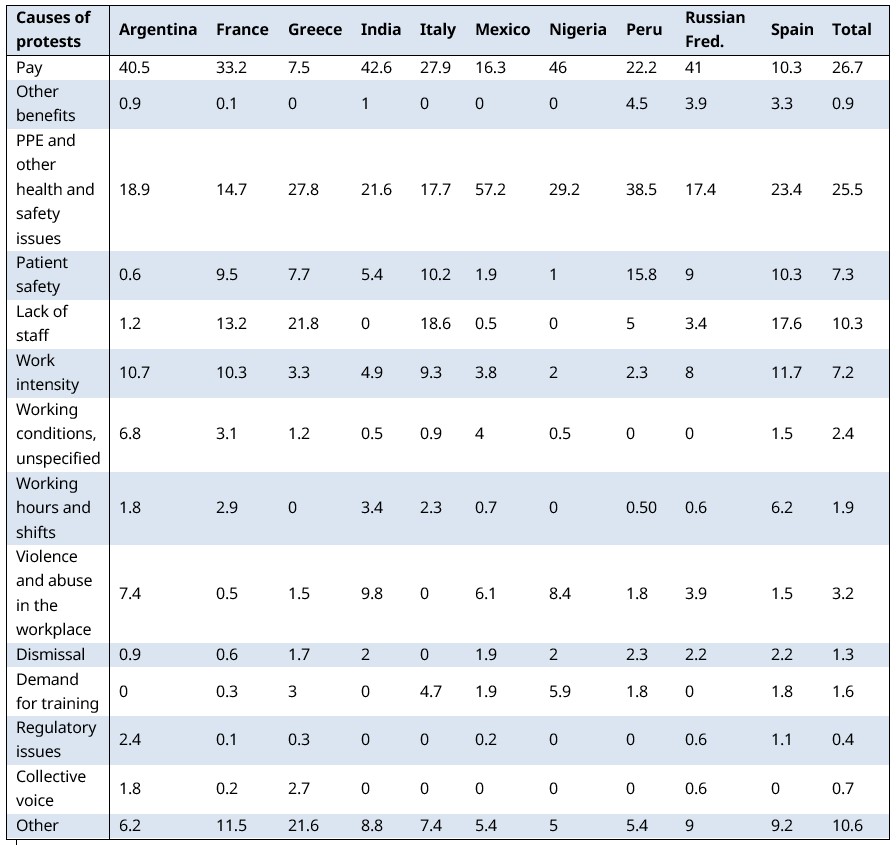

Table

Looking at individual countries (Table 6), the picture in healthcare offers some interesting observations. Looking at the 10 countries where most protests happened, health and safety and PPE were huge concerns that stimulated protest action – in Mexico and Peru it was the most common cause for protest action. In those countries 57.2 per cent and 38.5 per cent of protests, respectively, were about health and safety. However, also in those two countries, pay figured below average as a cause of protests, at only 16.3 per cent and 22.2 per cent compared to the mean of 26.7 per cent. Pay was also less of an issue in Greece and Spain, where lack of staff was instead the second most common concern. Lack of staff was also a prominent concern in Italy (18.6 per cent) and France (13.2 per cent).

Table

Table

|

Demonstration |

Leverage tactics |

Strike |

Strike announcement |

Other |

N |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

||

|

PPE + H&S |

|||||||||||

|

Africa |

31 |

15.3 |

62 |

30.5 |

85 |

41.9 |

14 |

6.9 |

11 |

5.4 |

203 |

|

Arab States |

1 |

6.3 |

10 |

62.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

5 |

31.3 |

16 |

|

Asia |

34 |

23.9 |

72 |

50.7 |

18 |

12.7 |

7 |

4.9 |

11 |

7.7 |

142 |

|

Europe |

155 |

26.3 |

207 |

35.1 |

153 |

26.0 |

58 |

9.8 |

16 |

2.7 |

589 |

|

North America |

24 |

36.4 |

16 |

24.2 |

17 |

25.8 |

8 |

12.1 |

1 |

1.5 |

66 |

|

Oceania |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

75.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

4 |

|

South America |

391 |

65.3 |

90 |

15.0 |

48 |

8.0 |

36 |

6.0 |

34 |

5.7 |

599 |

|

Pay |

|||||||||||

|

Africa |

31 |

12.9 |

37 |

15.4 |

115 |

47.7 |

46 |

19.1 |

12 |

5.0 |

241 |

|

Arab States |

2 |

8.7 |

13 |

56.5 |

2 |

8.7 |

1 |

4.3 |

5 |

21.7 |

23 |

|

Asia |

64 |

25.7 |

101 |

40.6 |

43 |

17.3 |

23 |

9.2 |

18 |

7.2 |

249 |

|

Europe |

224 |

25.2 |

174 |

19.6 |

314 |

35.3 |

139 |

15.6 |

38 |

4.3 |

889 |

|

North America |

28 |

38.9 |

13 |

18.1 |

15 |

20.8 |

9 |

12.5 |

7 |

9.7 |

72 |

|

Oceania |

4 |

30.8 |

1 |

7.7 |

6 |

46.2 |

1 |

7.7 |

1 |

7.7 |

13 |

|

South America |

237 |

59.4 |

45 |

11.3 |

42 |

10.5 |

46 |

11.5 |

29 |

7.3 |

399 |

Table

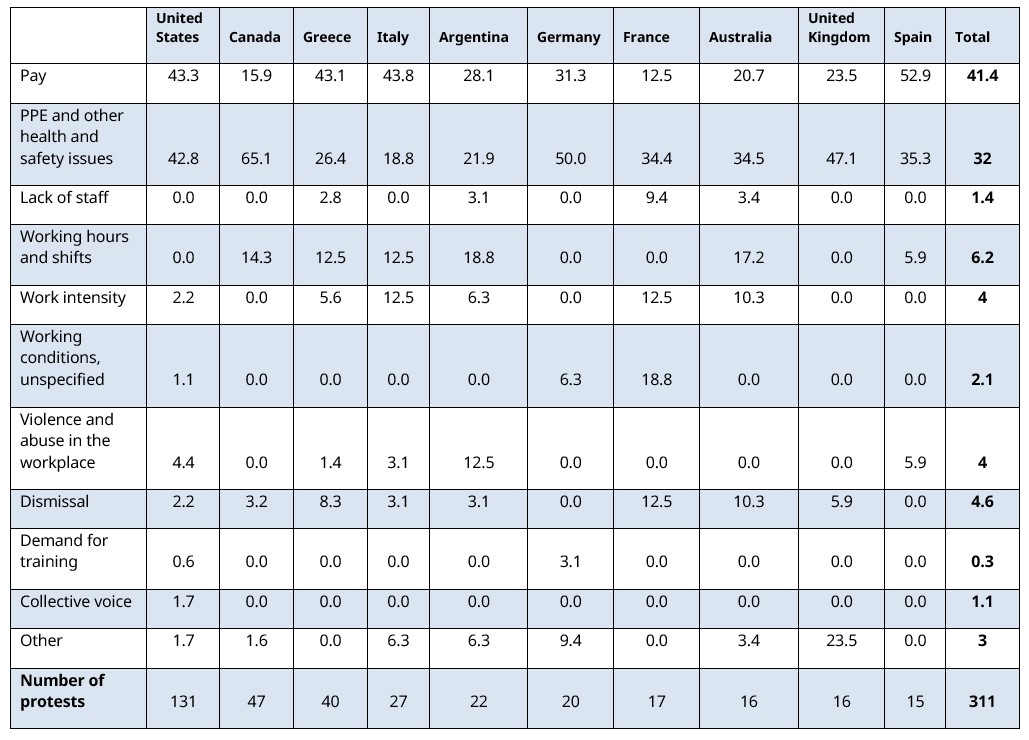

In retail, pay stimulated protest action more often in Spain than anywhere else. Interestingly, PPE and health and safety measures were the main reason for protest action in Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. This underlines how, despite these countries’ developed status and comparative wealth, vital provisions for frontline workers were still neglected including by huge retail giants – as our discussion of retail worker protests in the United States illustrates. In the United Kingdom and Germany, the main concern was the need to provide adequate PPE to workers. In the US and Canada, concerns were around access to vaccines for workers, COVID-19 testing and PPE, as well as emergency measures at stores, such as the number of customers allowed at once, the need for the enforcement of masks for customers, and local authority rules on mask and vaccine mandates.

Lack of staff was a prominent cause of protest among retail workers in France, and featured heavily in Australia, Argentina, and Greece. Overall, France was a particular protest hotspot, accounting for one out of 10 cases of protest; we consider the reasons for this below. Working conditions have been a a trigger for protests in various countries. Issues related to shift work featured heavily in the data for Argentina (18.8 per cent) and Australia (17.2 per cent), and work intensity an issue in Italy and France (12.5 per cent in each). Other working conditions grievance led to 18.8 per cent of protests in France, and 6.3 per cent in Germany. France also saw quite substantial protest around dismissals (12.5 per cent of all protest) as did Greece with 8.3 per cent.

3.2 Forms of protest action

Looking at how workers voiced their discontent, we observed four types of action were most common: demonstrations, strikes, strike announcements, and leverage tactics. These results are most interesting because they show that strike action was involved in only around 20 per cent of cases in both sectors. In some 80 per cent of cases, workers choose other means. An announcement of the intention to strike was referred to in 10.5 per cent and 14.4 per cent of cases in healthcare and retail respectively. However, the most common form of protests overall were public demonstrations in the healthcare sector, and leverage tactics in retail. The prominence of demonstrations is interesting, since the “social distancing” and on-off lockdown context might ostensibly be thought to obstruct the use of demonstrations, but this appears not to have been the case. We might also assume that key workers – especially in healthcare, which accounted for most of our cases – may have been less willing to take strike action during a health emergency, especially in hospitals. The widespread use of leverage tactics is less surprising, given this context.

Table

|

Type of Action |

Healthcare count |

Healthcare (%) |

Retail count |

Retail (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demonstration |

1359 |

35.1 |

120 |

25.8 |

|

Strike |

840 |

21.7 |

106 |

22.7 |

|

Strike announcement |

407 |

10.5 |

67 |

14.4 |

|

Leverage tactics |

1033 |

26.7 |

144 |

30.9 |

|

Other |

231 |

6.0 |

29 |

6.2 |

|

Total |

3870 |

100 |

466 |

100 |

Once more, the picture in different regions is one of variation. In healthcare, strike action was the first choice of action in the Arab States, as in Asia, and Europe. In North America, South America, and Oceania the first choice has been demonstrations, and leverage tactics in Africa. Strikes were not widespread in South America, only comprising 14.9 per cent of protest cases. In retail, strikes have been part of on average 22.7 per cent of protest events, but much more often in Africa and Oceania where it was the preferred method in 38.8 per cent and 40.9 per cent of cases respectively.

The low number of strikes in South America contrasts with an unusually high number of demonstrations: 62.2 per cent in healthcare compared to the average of 35.1 per cent, and 41.2 per cent compared to the average of 25.8 per cent in retail.

Table

|

Type of Action |

Africa |

Arab States |

Asia |

Europe |

North America |

Oceania |

South America |

Total |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

Health |

Retail |

|

|

Strike |

25.3 |

38.9 |

57.7 |

0 |

37.7 |

17.6 |

30.3 |

24.1 |

21.6 |

25.8 |

25 |

40.9 |

14.9 |

0 |

21.7 |

22.7 |

|

Strike announced |

6.9 |

0 |

23.1 |

0 |

8.6 |

5.9 |

3.9 |

15.4 |

6.4 |

18.5 |

12,5 |

4.5 |

6.6 |

5.9 |

10.5 |

14.4 |

|

Demo |

15.7 |

50 |

7.7 |

0 |

29.3 |

58.8 |

26.9 |

21.0 |

36.8 |

25.8 |

29.2 |

9.1 |

62.2 |

41.2 |

35.1 |

25.8 |

|

Leverage tactics |

37.7 |

0 |

7.7 |

0 |

17.1 |

17.6 |

26.2 |

35.4 |

24.0 |

25.8 |

29.2 |

40.9 |

9.4 |

50 |

26.7 |

30.9 |

|

Other |

14.4 |

11.1 |

3.8 |

100 |

7.3 |

0 |

12.8 |

4.1 |

11.1 |

8.4 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

7.0 |

2.9 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

|

N |

451 |

18 |

52 |

2 |

509 |

17 |

1674 |

195 |

171 |

22 |

24 |

34 |

989 |

34 |

3870 |

466 |

Interestingly, leverage tactics were most common in South America and Oceania in retail, and in Africa in healthcare.

Looking at those countries with the highest number of protest events in the healthcare sector, demonstrations were the most widespread method, but with some exceptions where strikes were very common, including France and Nigeria. Public pressure through leverage tactics were most widespread in Greece and the Russian Federation.

Table

|

Country |

Strike |

Strike announcement |

Demonstration |

Leverage tactics |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina |

12.2 |

10.5 |

59.9 |

5.2 |

12.2 |

|

France |

61.5 |

20.8 |

15.2 |

2.5 |

0 |

|

Greece |

17.4 |

11.2 |

27.0 |

44.4 |

0 |

|

India |

23.4 |

13.7 |

45.1 |

8.6 |

9.1 |

|

Italy |

11.5 |

13.9 |

36.1 |

37.7 |

0.8 |

|

Mexico |

8.2 |

3.9 |

78.5 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

|

Nigeria |

63.9 |

12.3 |

9 |

8.2 |

6.6 |

|

Peru |

6.2 |

9.2 |

55.4 |

26.2 |

3.1 |

|

Russian Federation |

0 |

1.8 |

6.3 |

86.6 |

5.4 |

|

Spain |

4.9 |

14.6 |

37.5 |

36.8 |

6.3 |

|

Average for all 10 countries |

25.5 |

12.1 |

38.2 |

20.3 |

3.9 |

|

N |

513 |

243 |

767 |

407 |

79 |

3.3 Discussion of main quantitative findings

The descriptive statistics presented here are only a first step in understanding protest in retail and healthcare work during COVID19. Limitations of the dataset – particularly reliance on news reports, the absence of comparable pre-pandemic data and the need for more in-depth qualitative analysis – mean conclusions must be tentative. One particularly clear finding is that, during the period we examined, protest in healthcare greatly outweighed protest in critical retail. We are not able to explain this difference without additional research, but possible reasons can be tentatively identified, subject to further examination. As noted in the discussion of previous research, frontline service sector work may require few qualifications and may be highly precarious, and therefore may have experienced relatively high rates of staff turnover during the pandemic: that is, retail may have seen a tendency toward exit rather than voice. While there is little data on turnover in retail, studies of other types of frontline service work suggest a spike in voluntary quits (e.g., De Souza Meira, 2021; Jung et al, 2021). By contrast, healthcare work features specialised career and progression routes, making it more likely that healthcare workers would exercise voice rather than exit. This effect is likely to be strengthened by the higher prevalence of unions in healthcare compared to retail.

The overall dataset also reveals interesting findings about the causes and reported triggers of worker protest. Unsurprisingly, concerns around PPE and other health and safety concerns are prominent. These acute issues became pre-eminent grievances for workers as the pandemic took hold. These findings are deeply poignant, in that they illustrate the desperate situation many workers faced as they battled to keep services running while being undersupplied by governments and employers. However, while this is a vital part of the story, it is not all of it. The prevalence of pay as a cause of protest suggests that, in many cases, workers were not responding defensively only to immediate threats to their health from the dangers of COVID19 transmission. Rather, we suggest that the new prominence given to these key workers in the public eye, combined with the extraordinary demands placed upon them, may have in some cases generated greater assertiveness and confidence in pushing for wider progress over pay and conditions of work. Indeed, in some cases, as we will show, this was an explicit objective. At this stage, we cannot generalise from this data about worker protest in these sectors on a global scale. However, our commentaries on individual countries will add some corroboration to this analysis.

Finally, the dataset reveals significant variation between countries and regions. Political, economic, and institutional contexts clearly matter in shaping patterns of protest. Nevertheless, over-generalisation about the role of national institutional factors should be resisted, given the huge differences we found within countries. For example, a comparatively large volume of protest were identified in healthcare in India but very little in retail, and the same can be said of Nigeria; we therefore examine reports from these country cases in more detail below. Moreover, among the handful of countries reporting no protests, there is no consistent economic or institutional profile. Hence, we suggest that spikes in protest in particular sectors and countries are likely to reflect not only the national institutional context, but also contingent factors and strategic decisions made by the actors involved. To illustrate this point, we examine in more detail reports from the five countries with the highest levels of protest in the two sectors: France, India and Nigeria for healthcare, and the United States and Argentina for retail.

3.4 Healthcare in France

Why is France, by some distance, the country where healthcare workers have protested the most frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic? The uniquely high volume of protest in French healthcare during the pandemic period reflects various distinct but interrelated factors, including contextual factors which predate the pandemic (the marketisation of French healthcare), and, importantly, strategic decisions made by French unions as the pandemic gained pace.

First, it is important to understand that, in the period immediately preceding the pandemic, protest action among healthcare workers in France had been increasing. Several years of budget pressure in the healthcare sector in France had led to reductions in staffing levels and the closure of numerous local hospitals. In addition, these budget restraints were also accompanied by various market-centric reforms to hospital governance and financing systems, which had led many healthcare workers and their unions to identify a shift to a more “business-facing” hospital, and to which many in the sector strongly objected (Umney and Coderre-LaPalme, 2017; 2021). Hence, even days before the scale of the pandemic became apparent and lockdowns began, there were instances of protests including strikes demanding more recruitment to reduce workload in Nantes8, and demonstrations against job losses in Carcassonne9.

However, just as much as institutional and economic context, the approaches and decisions of key union leaders in France are relevant in explaining workers’ responses to the pandemic. Phillippe Martinez, General Secretary of the CGT, made the following statement in February 202110, reflecting the union’s approach:

“This Thursday, we affirm, at the national and interprofessional level, that it is impossible to set to one side current struggles for jobs and the improvement of working conditions in the name of a pseudo-national unity against COVID-19… Bruno LeMaire tells us that it’s not the time for a Social Spring. On the contrary!”

Hence as the crisis developed, key unions decided to maintain pressure over their existing objectives rather than making concessions. They had been mobilizing around issues of inadequate resources and staffing levels and COVID-19 exacerbated these concerns.11 Some resisted various emergency Covid-related measures which they felt undermined job security and proper career training; for example, protesting against the reallocation of nurses on placement to the frontline in Montauban.12 In Libourne, Force Ouvrière argued that COVID-19 was being used as a pretext for reorganisation and changes to working hours that were detrimental to workers.13. Unions also claimed that French authorities were trying to handle the pandemic while holding firm to their pre-existing budget restraint priorities, which workers and unions saw as a major obstacle to providing proper care as well as a threat to jobs.14

Consequently, in the news reporting on French protest, we observe healthcare workers and their unions seeking to bring together emerging Covid-related concerns (such as the drain on hospital resources and need for more equipment) with pre-existing concerns over jobs and working conditions in the framing of their disputes.15 Unions and other campaigners argued specifically and repeatedly that the pandemic was exposing existing problems whose root causes were government policy long predating Covid, pushing the sector towards the “hôpital-entreprise” model. The use of this framing in mobilising workers is a near-constant in the news reporting on many protest events, as shown in accounts of protest from early in the pandemic in Paris16, Bourdeaux17, Creuse-Gueret18, Creteil19, Lyon,20 and Saint-Brieuc21, to name but a few of many examples, as well as in national-level calls for action.22 This framing appears to have been applied across many different professional and occupational groups within healthcare, including a strike by hospital human resource administrators in Dreux, who argued that the pandemic has exposed the need for more staffing to reduce excessive workload.23

The strains placed on healthcare staff during the pandemic underlined union demands, providing them with a strong moral force which could be invoked to support their longer-standing claims. The CGT, for instance, sought to link problems which became particularly acute during the pandemic (such as aggressive patients), to a wider narrative about the deterioration of working conditions.24 Unions argued that the measures introduced to mitigate Covid-related pressures were unable to make up for the damage caused by previous decisions.25 Interestingly, in a few minor cases, the deterioration of social dialogue within hospital management structures was cited as another pre-existing problem, exacerbated by emergency COVID-19 measures (protests in Creuse26 and Caussade27). As other research has shown (Greer and Umney, 2022), weakness of social dialogue and accountability have been associated with marketisation and outsourcing, particularly in hospitals. Workers continued to protest against this even in cases where relevant articles make little reference to the pandemic itself; as in protest by outsourced cleaning workers in Parisian hospitals.28

Hence a vital part of the picture in France is the decision of unions to continue to mobilise, and wherever possible, draw links between acute COVID-19-related issues and the longer-term deterioration of working conditions in healthcare. As such, many of the articles reporting protests frame demands as a bundled of concerns, particularly resources, pay, jobs and work intensification. It is interesting that specific COVID-19 related concerns for healthcare and other workers during 2020 – 2021, such as the provision of PPE and other safety measures, are virtually never mentioned as primary triggers of protests in France. The strategy appears to have been to broaden the scope protests by linking COVID-19 specific demands with other issues.

Pay, in particular, is of vital importance given its prevalence in the quantitative protest data, and speaks to an increasing assertiveness in demanding the reversal of deteriorating working conditions and pay stagnation; given the new moral and discursive force of the image of healthcare staff as frontline workers putting themselves at risk.29 However, one reason that so many protest events are reported around pay in France during the pandemic lies in unions’ responses to one particular government intervention: the Ségur de la Santé was a consultation running from May - July 2020 to discuss resources and organisation of healthcare in the pandemic. It resulted in some pay increases for selected healthcare staff to acknowledge their service during the pandemic. However, the scale of these were disappointing for many, and so reaction against this central intervention catalysed a large number of protest events. More protest events are reported in France relating to this one policy alone, than the total for many other countries. These were either motivated by a belief that the extra payments were inadequate given the scale of the problem30; or, even more frequently, reflect protests by specific groups of healthcare workers that were excluded from these additional payments such as psychiatric practitioners and midwives.31 This also included private healthcare workers who felt unjustly underpaid compared to public counterparts and who were excluded for the Ségur de la Santé pay increases, as exemplified by protests in Lyon32 and Wissembourg33. The number of articles describing protests on this specific issue is vast. Relatedly, a centrally-developed special subsidy scheme also prompted large amounts of protest, since it prioritised hospitals in regions that had been hardest-hit by Covid and was perceived as unjust and exclusionary by some.34 Perceived inequalities in these central interventions exacerbated the sense that certain professions (such as that of midwives) where undervalued by public authorities.35

Some other themes emerge which, while not present in the majority of cases, nevertheless deserve mention. While precarity is not as widespread in French healthcare work as in many other industries or countries, a number of sources suggest it as a source of protest.36 The use of fixed-term contracts, again, is a pre-existing issue which had been a source of contention pre-pandemic in the context of hospital budget cuts and attempts to weaken the status of civil servants in healthcare. However, issues related to the precarity of atypical employment were also likely exacerbated by the pandemic. One dispute in Drôme, for instance, related to a hospital’s attempt to terminate workers who had been hired at the start of the pandemic to make up emergency shortfalls in staffing.37 Disputes over working time were notable, given how working time is enshrined in national-level regulations. For instance, strikes in Corsica ensued after a local hospital appeared to delay the implementation of a central government decree granting staff payment for leave that had not been taken38.

Finally, the potential for a high number of reported protest events also reflected the willingness of French unions and campaigners to engage in collective action, including on a national scale. National days of action were organised by unions and non-union campaigning organisations and led to many smaller events across the country. Again, these typically took a broad focus, framing many different concerns as part of a wider narrative about deterioration of working conditions in healthcare, and at different times accentuating the issues of different occupational/professional groups. These various days of action generated a large volume of protest activity across many French regions.39