Engendering informality statistics: gaps and opportunities

Working paper to support revision of the standards for statistics on informality

Abstract

Informality is a dynamic and multidimensional concern that demands gender-sensitive data. In 2018, globally, more than 60% of employment was informal. However, global averages hide that in more countries the share of women in informal employment exceeds that of men. Also, women in the informal economy are often in the most unprotected situations – as domestic workers, home-based workers and contributing family workers – where a lack of visibility can increase their vulnerability.

The ILO and its partners are working to engender informality statistics to improve gender data and support countries to respond to data needs on women’s economic empowerment. This working paper was written to support the ILO Working Group for the Revision of the standards for statistics on informality. It explores the demand for gender data on informality and the measurement challenges faced. The paper highlights the opportunities emerging from the revision of statistical standards on informality that are set to be adopted in 2023.

Key points

-

Informality broadly refers to jobs and enterprises that lack coverage by formal arrangements, be that in law or in practice. Informality exists in high income countries but is most often found in low- and middle-income economies.

-

Informality is a dynamic and multidimensional concern that demands gender-sensitive data. Engendering Informality Statistics is aligned with the ILO’s shared goal to improve gender data and support countries to respond to data needs on women’s economic empowerment.

-

There is a strong demand for gender and informality statistics, to inform national policymaking processes and support reporting on commitments such as the SDGs, Recommendation 204 on transition from the informal to the formal economy, CEDAW, and the Beijing Platform for Action.

-

In 2018, globally, more than 60% of employment was informal. Informality is common among both women and men. Global averages hide that, in more countries the share of women in informal employment exceeds that of men. Another gender dimension is that women in the informal economy are often in the most unprotected situations – as domestic workers, home-based workers and contributing family workers – where a lack of visibility can increase their vulnerability.

-

Women’s economic empowerment and informality are interconnected. Gender norms and economic structures impact the opportunity and choice of employment for women and men, and their options to transition from informal to formal work.

-

Gender roles shape how women and men participate in household surveys and can bias the information given about the work they do.

-

There have been important achievements in improving informality statistics since the first standards were adopted in 1993. The revision of standards is an opportunity to focus attention on where the significant challenges and gaps remain. Data and gender analysis are needed to quantify, describe, and contextualize informality and make comparisons to the formal sector and jobs.

-

Monitoring progress towards gender equality demand statistics on unpaid domestic and care work, access and control of economic resources, the use of information and communication technologies, and the participation and influence of women in leadership and decision-making, all of which have connections to informality.

-

Challenges for gender-responsive informality statistics stem from a lack of universal measurement of informality, infrequent production, or statistics not being harmonized with current standards. Accurately identifying status in employment is a challenge. Also, gender bias in participation and reporting in household surveys, and gaps in gender-sensitive analysis and dissemination.

-

Engendering informality statistics involves responding to the growing needs for gender data and ensuring the new standards and indicator framework can adequately respond. It includes exploring how potential changes to informality measures will impact gender statistics. Technical assistance and capacity development are vital to support data collection and production of the new measures of informality. Also, tools and support to ensure the resulting data are analysed with a gender focus and made more accessible.

Introduction

Informality is a dynamic and multidimensional concern that demands gender-sensitive data. Globally, the informal economy is the source of livelihood for most women and men. The issue is at the centre of social wellbeing, economic growth, and reducing inequalities, particularly in emerging and developing economies where informality rates remain high, but also in developed economies.

The size and nature of informality varies considerably between countries. It is a major feature of developing economies, where making equitable progress depends on quality data, careful planning, and inclusive policies. It is also a relevant issue in developed countries, where an increasing number of people are in non-standard forms of employment1 and informality may grow, particularly during recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Digitalization, globalization, and economic shocks can be drivers of informalization. Monitoring those trends and causal relationships is just as relevant in developed countries as in developing countries.

The ILO Department of Statistics is committed to strengthening gender data in all areas of its work. The Department has prepared this working paper to support the current revision of global standards for measuring informality. It is a key output from the Engendering Informality Statistics project, which is running in parallel to support the ILO Working Group for the Revision of the standards for statistics on informality.

1.1 The need for new standards for measuring informality

Photo of proceedings at the 20th international Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) held in Geneva, 10-19 October 2018.

Source: ILO Newsroom

The International Conference for Labour Statisticians (ICLS) adopted the existing standards that guide countries to measure informality in 1993 and 2003. While they still hold relevance today, they lack prescription, reflecting the need for flexibility that existed at the time. The standards need updating to respond to changing data requirements triggered by changes in employment and by changes to statistical definitions over the last decade.

Key among the new statistical definitions to be incorporated in the informality statistics standard is the conceptual framework for measuring all forms of work, adopted by the 19th ICLS in 2013. It introduced the first internationally agreed reference concept of ‘work’ that includes own-use production, volunteering, and unpaid trainee work, and redefined employment as being limited to activities done in expectation of pay or making a profit. Further to this, a new International Classification for Status in Employment (ICSE-18) adopted together with an International Classification of Status at Work (ICSaW-18) in 2018, both impact on how to measure informality and need to be incorporated.

The revision of the statistical standards for measuring informality was initiated by the last ICLS in 2018. Coordinated by the ILO, a working group was established to complete the review, comprising representatives from national statistical systems, international agencies, and development partners. Following its first meeting in October 2019, the group meets annually with subgroups organized to further develop key areas between annual sessions.

The 21st ICLS in 2023 will discuss the adoption of the new framework on the Informal Economy being drafted by the working group. A comprehensive indicator framework is being developed and will accompany the standards to guide the production, analysis and uses of data. This is a new element of the standards that did not exist before. It envisions to provide both a framework for measurement and guidance on the actionable statistics that can be produced as a result. This important process is an opportunity to ensure a gender perspective is integrated in how informality is measured and how the resulting data are used to inform gender sensitive and transformative policies. A project developed in partnership between the ILO and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has been established to this end.

1.2 Engendering Informality Statistics Project

Since 2020, the ILO Statistics Department is leading a project to engender informality statistics in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In addition to this paper summarizing key measurement issues for gender and informality, the main activity of the project is to test statistical concepts and household survey questionnaires to generate evidence on what works when collecting data. Cognitive interviews were used to test survey questions in 2021 and pilot field tests of alternative LFS questionnaires in 2022 will provide quantitative data for analysis of measurement approaches with a gender lens. The findings from those tests will support the working group in its discussions and drafting of the standards and in guiding countries on implementation, data production and analysis.

Alongside the testing, the project is also assessing the existing and anticipated needs for gender data on informality and reviewing the uses of data in strategy setting and policy formulation, making recommendations to strengthen the production, accessibility and use of gender statistics on informality.

1.3 Purpose of this paper

This paper presents a summary of the main issues pertaining to gender and informality statistics. It explores the demand for data and which topics are emerging as high priorities for the future. It summarizes measurement challenges and gaps, pointing to issues for consideration and resolution in the development of new standards. It outlines where opportunities exist and can be capitalized on to improve gender data on the important topic of informality.

This paper is intended both to guide a broad audience on issues related to engendering informality statistics and support the working groups as they complete their work on the revised standards, associated indicators, and guidance on the new measures after their anticipated adoption in 2023.

Key terms

Gender refers to the roles, behaviours, activities, and attributes that a given society at a given time considers appropriate for men and women.

In addition to the social attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys, gender also refers to the relations between women and those between men.

These attributes, opportunities and relationships are socially constructed and are learned through socialization processes. They are context/ time-specific and changeable.

Gender equality refers to the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys. Equality does not mean that women and men will become the same, but that women’s and men’s rights, responsibilities and opportunities will not depend on whether they are born male or female. Gender equality implies that the interests, needs and priorities of both women and men are taken into consideration, recognizing the diversity of different groups of women and men. Gender equality is not a women’s issue but should concern and fully engage men as well as women. Equality between women and men is seen both as a human rights issue and as a precondition for, and indicator of, sustainable people-centred development.

Gender equity is used in some jurisdictions to refer to fair treatment of women and men, according to their respective needs. This may include equal treatment, or treatment that is different but considered equivalent in terms of rights, benefits, obligations and opportunities. The preferred terminology within the United Nations is gender equality, rather than gender equity. Gender equity denotes an element of interpretation of social justice, usually based on tradition, custom, religion or culture, which is most often to the detriment to women. Such use of equity in relation to the advancement of women has been determined to be unacceptable. During the Beijing conference in 1995 it was agreed that the term equality would be utilized.

Source: UN Women, Gender Equality Glossary (unwomen.org)

Engendering statistics is an expression first used in the 1996 Engendering Statistics: a Practical Tool, a publication by Statistics Sweden, a leader in the field of gender statistics. It promotes the integration of gender in all stages of the statistical production process starting with close cooperation between users and producers of statistics, ensuring statisticians understand gender concerns, and users are statistically literate. A gender perspective is applied from deciding what to measure, revisiting methods to ensure statistics reflect the realities of women and men’s lives and applying a gender lens to analysis and dissemination.

The informal economy constitutes all informal productive activities of persons and economic units whether or not they are carried out for pay or profit. The informal economy includes the narrower concept of the informal market economy, defined as all productive activities, carried out by workers and economic units for pay or profit that are – in law or in practice – not covered by formal arrangements.

This is the statistical definition proposed by the ILO Working Group on the Revision of the standards for statistics on informality for discussion at the 21st ICLS.

Source: ILO. October 2021. Draft Resolution concerning Statistics on the Informal Economy.

Informality is a term used to describe productive activities, economic units, jobs and work activities that are - in law or in practice - not covered by formal arrangements and therefore forms part of the informal economy.

Informalization refers to the increase of informality compared to formality in an economy. This could be due to workers shifting from formal to informal jobs – a trend linked to digitalization, globalization, and economic shocks. It could also stem from disproportionate growth of informal work compared to formal work.

Source: ILO, 2013. Measuring informality: A statistical manual on the informal sector and informal employment.

Informal sector – the statistical definition refers to a production unit based concept (e.g., enterprise or own-account operator). The sector consists of units engaged in the production of goods or services with the primary objective of generating employment and incomes to the persons concerned. These units typically operate at a low level of organization, with little or no division between labour and capital as factors of production and on a small scale. Labour relations – where they exist – are based mostly on casual employment, kinship or personal and social relations rather than contractual arrangements with formal guarantees.

Source: ILO, 2013. Measuring informality: A statistical manual on the informal sector and informal employment.

Informal employment – is proposed to be defined as any activity of persons to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit that is not effectively covered by formal arrangements.

Informal employment comprises activities carried out in relation to informal jobs held by:

-

-

Independent workers who operate and own or co-own an informal household market enterprise;

-

Dependent contractors who operate and own or co-own an informal household market enterprise or whose activities are not registered for tax and statutory social insurance;

-

Employees, if their employment relationship is not in practice formally recognized by the employer in relation to the legal administrative framework of the country and associated with effective access to formal arrangements;

-

Contributing family workers who are not formally recognized in relation to the legal administrative framework of the country and associated with effective access to formal arrangements.

-

Source: ILO. October 2021. Draft Resolution concerning Statistics on the Informal Economy.

Demand for measuring informality with a gender perspective

The concept of an informal sector was devised in 1972 to describe the realities of the labour market found in Kenya at the time.2 Found to be widely relevant, the concept was soon integrated in employment policymaking and in labour force statistics.

Informality refers to productive activities, economic units, jobs and work activities that are – in law or in practice – not covered or insufficiently covered, by formal arrangements3 (see Key Terms on page 9 for more explanation). Often associated with poverty, underdevelopment, underemployment, and vulnerability, the informal economy is a significant provider of jobs and income. In 2018, informal employment was a source of work for around 2 billion workers4 and while transitioning from informal to formal economies is a priority, informal employment is not going away any time soon.

The main concerns with the informal economy are “the lack or low coverage of social protection, poor or hazardous working conditions and generally low remuneration and productivity, and a lack of organization, voice and representation in policy-making”.5 Megatrends like digitalization and globalization may see informality emerge in economies and occupations where it was not prevalent before. By providing economic opportunities where more stable wage employment is lacking, data on informality make some contribution to the global goals for achieving gender equality. The informal economy may not be seen as desirable, but it is important. It has been characterised by ease of entry, small scale of operation, reliance on indigenous resources, and family ownership – characteristics that are aligned with sustainable development, women’s economic empowerment, and gender equality.6 Integrating gender into its measurement and analysis is essential to design policies and empower women in informality.

Addressing gender inequalities in the context of informality began through programmes targeting poor women in rural areas and the informal economy.7 Since then, increasing research and data on women’s economic empowerment and informal versus formal work has supported more targeted policies and programmes. The available research shows that an intersectional approach is needed to identify and target policies to ensure no one is left behind.8 For example, analysis with an intersectional lens has found that women face structural and social barriers in access to credit, technology, business services, training, and the market compared to men.9 Such factors impact their capacity to start formal businesses or grow their enterprise to a point where formalization is feasible. Regular measurement of informality and contextual data can support better programmes for women and men.

2.1 How does informality differ between women and men?

|

|

Fish sellers from Chisinau (Republic of Moldova) at their stand on a marketplace (April 2010).

Photographer: Crozet M.

|

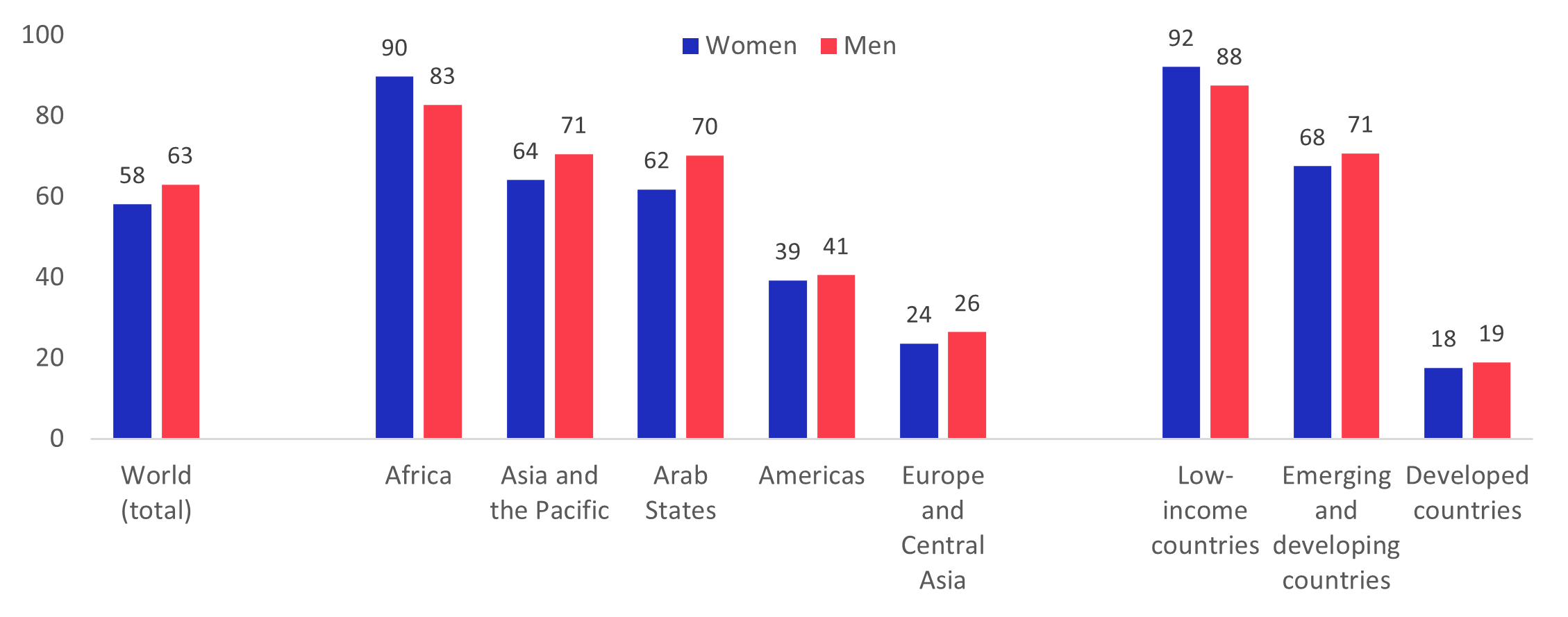

The most recent estimates show most of the global workforce is informal (61% of total employment) and there is a slightly higher share of men in informal employment (63%) than women (58%) (Figure 1). Regional data reveal that informality is highest in the world among women in Africa and lowest in Europe and Central Asia (24% of employed women; 26% for men). In Africa, 90% of employed women are informal compared to 83% of men. Gender differences are largest in the Arab States where 70% of employed men are in informal employment compared to 62% of employed women.

Figure 1: Share (%) of informal employment in total employment (including agriculture) by sex, 2016

Source: International Labour Organization. 2018. Women and Men in the Informal Economy - a statistical picture, Third edition.

Source: International Labour Organization. 2018. Women and Men in the Informal Economy - a statistical picture, Third edition.

Regardless of average rates, there are important gender dimensions that influence informal work, as well as how it is measured. In low and low-middle income countries, where women’s economic empowerment is fundamental to lifting people out of poverty, the rates of informal employment are higher among women than men.

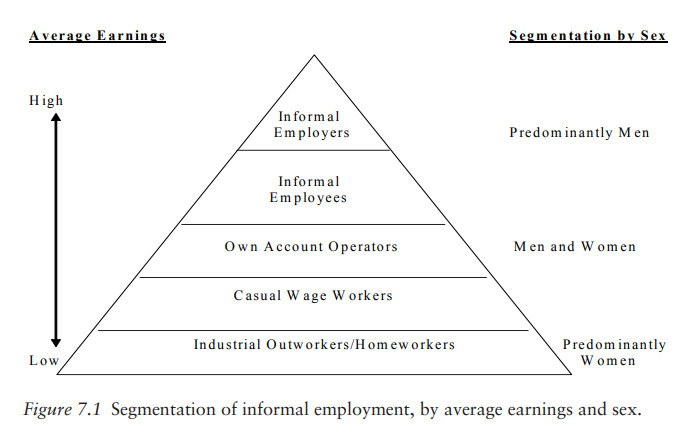

Gender also influences women’s position within the informal and formal economies. This highlights the need for indicators that compare between informality and formality but also to show how conditions within informal work compare between women and men. In countries with high rates of informality, the formal sector and informal sector units may not be distinct entities. Formal enterprises may hire informal workers, for example, so the distribution of informal employment is also important to consider. Women and girls are disproportionately represented in some of the most unprotected situations in the informal economy, such as waste pickers, street vendors, domestic workers, and home-based workers.10 These groups face specific challenges. Domestic workers and home-based workers share an invisibility that comes with working in an employer’s private home or their own home, each with distinct vulnerabilities. This sees them isolated from others with more likelihood of being hidden from regulators and cut off from support networks.11 Domestic workers can be hard to reach in household surveys and are excluded from business and establishment surveys. The types of informal businesses run by women and the informal jobs they occupy are often less stable compared to men. Even when women and men do similar forms of informal (or formal) work, there is a gender gap in earnings (Figure 2).12 In the 19 countries where data are available, hourly wages for women in the informal economy are less than for men in informal employment.13

Figure 2: Diagram illustrating gender gaps in types of informal work and associated earnings

Source: Chen, Martha Alter. 2008. "Informalization of labour markets: Is formalization the answer?" in Shahra Razavi .ed. The Gendered Impacts of Liberalization. New York: Routledge.

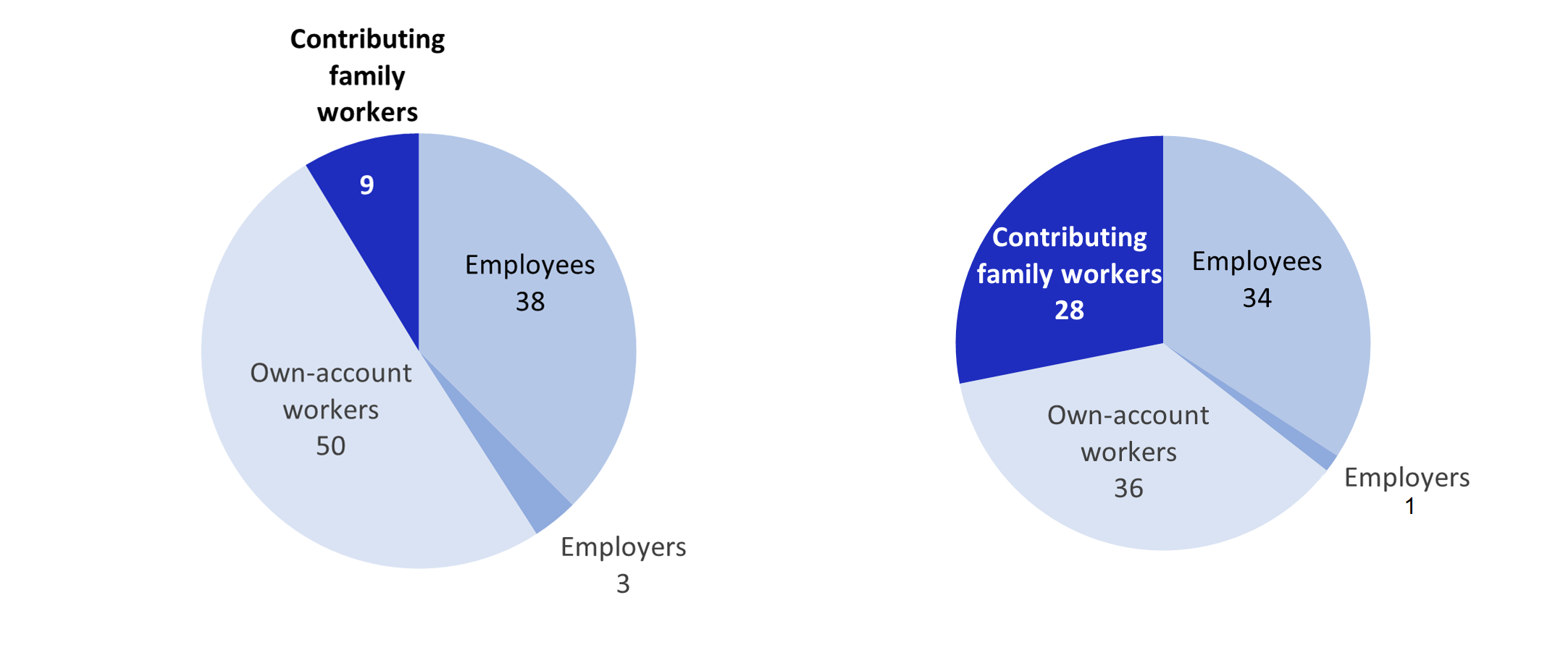

Another gender element of informality statistics stems from the statistical classification of status in employment. A minor but significant group of dependent workers in informal employment are contributing family workers.14 Globally the size of this group is shrinking fast. There is some evidence that contributing family work can tend to be misclassified with own-account work and vice-versa.15 Follow-up questions are recommended to better understand the role in the family business and classify the status in employment correctly.

In 2019, contributing family workers made up only 9% of total global employment, down from 20% in 1991, linked to a decrease in agricultural activities.16 The situation is significantly different between high and low-income countries. In 2019, high income countries had almost no contributing family workers (less than 1% of total employment) but in low-income countries, 29% of employed people were contributing family workers.17 The ILO World Employment and Social Outlook 2022 report provides evidence that the incidence of contributing family work increased in 2020, with a faltering labour market pushing more people to contribute to family enterprises.18 While contributing family workers are currently classified as informal by default in statistics, formal arrangements are being extended to them in some countries.

Contributing family workers are mostly women (63% in 2020),19 which may be indicative of gender norms that make it more likely for women working in family enterprises to not be involved in decisions on how that business is run. A striking finding from an ILO study on measuring employment suggests the contributing family worker status persists for women as they age, but not so for men. In that study, a high and similar proportion of women and men aged 15-24 were contributing family workers (27% of women and 25% of men). Among people aged 45 to 64 years, the rates remained relatively high for women (17%) but were much lower for men (5%).20

The impact of gender norms on status in employment shows clearly in the data (

|

Honey and cheese cooperatives created in Cahul district in Moldova formalized jobs for 35 contributing family workers.

Source: ILO Newsroom |

|

Figure

2.2 Demand for gender and informality data

National development strategies and policies are the main source of demand for official statistics. They typically require gender data for informed policymaking across all sectors, as well as for policies specific to gender equality.21 The global development agenda, the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), demonstrates the cross-cutting nature of gender and the importance of engendering statistical work. Each of the 17 global goals has indicators used to monitor progress – around one third requiring gender data – either sex-disaggregated data or data about gender-related concerns (e.g., gender-based violence against women, women in leadership).

In 2015, Recommendation 204 concerning the transition from informal economy to the formal economy was adopted by the International Labour Conference.22 It states that a large informal economy challenges the rights of workers and has a negative effect on development. It acknowledges that most people enter the informal economy due to the lack of opportunities in the formal economy rather than by choice. It sets the transition to a formal economy as a policy priority with the promotion of gender equality as one of the guiding principles to achieve it. This ambition is integrated in the global goals, with SDG target 8.3 encouraging formalization and growth of micro, small- and medium-sized enterprises. The ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work promotes the transition from informal to formal economies and the importance of strengthening institutions to monitor the extent of informality.23

Informalization – the potential increase of informal employment relative to formal employment - is also of concern for policymakers and producers of labour market statistics. Informalization can occur when workers shift from formal to informal jobs – a trend linked to digitalization, globalization, and economic shocks – or there is disproportionate growth of informal compared to formal work. Informalization is relevant to developed and developing economies.

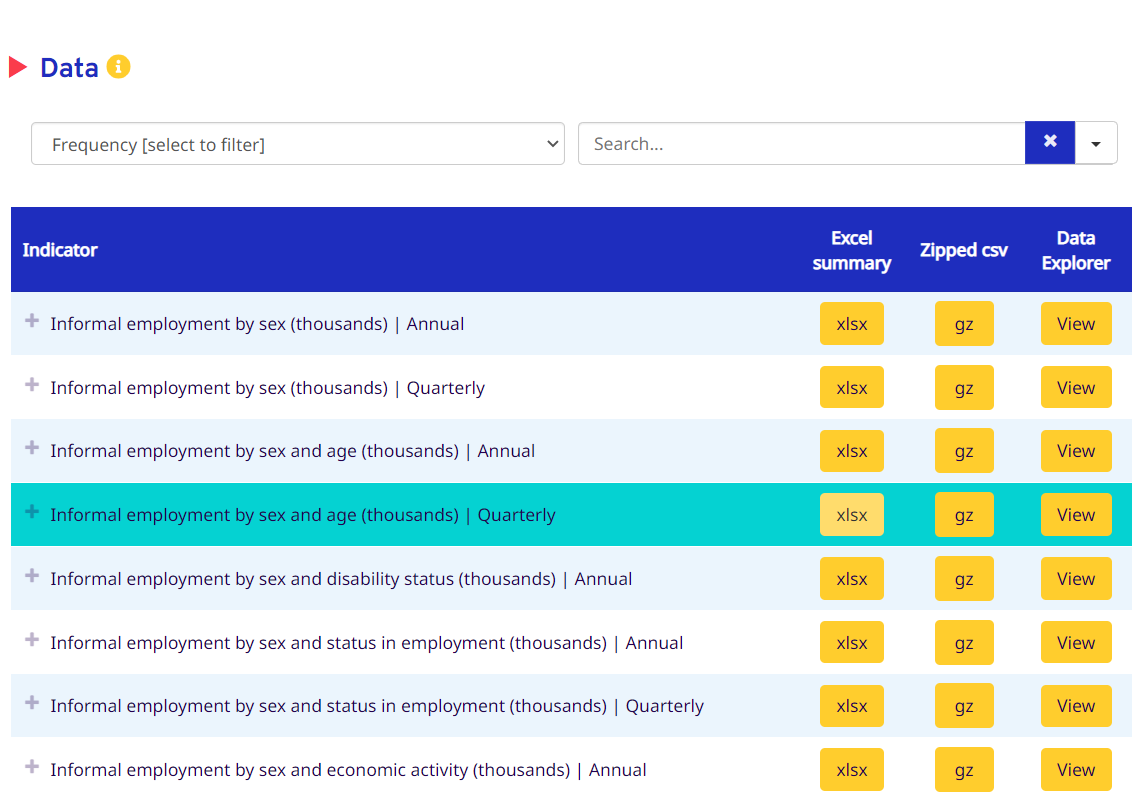

To monitor progress towards these goals, countries need evidence of the size and nature of the informal economy and women and men’s roles within it. SDG indicator 8.3.1 requires regular production of data on the proportion of informal employment in total employment, disaggregated by sex. Recommendation 204 calls for the regular production of statistics on the informal economy disaggregated by sex, age, and other characteristics. Regular, reliable, and disaggregated data is needed for different policymaking priorities. For example, a life cycle perspective to policy formulation would mean enabling transitions from informal to formal work across age groups and not just concentrating on ending informality amongst young people.

Example of the informality statistics available on ILOSTAT (ilostat.ilo.org) – the leading source of labour statistics.

Source: ILOSTAT

Beyond these specific reporting requirements, gender data on informality are used for monitoring progress towards broader gender equality commitments, such as to the Beijing Platform for Action and the Convention for the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Countries that have committed to these norms need to report regularly on their progress to meeting those goals. Such reports need official statistics and analysis to illustrate persistent and emerging gaps and to show where progress is being made. This signals the need for guidance on producing and using gender data across all areas of statistics.

Data needs around informality could be divided into two broad areas:

-

Quantifying the informal economy – the data, statistics, and indicators on the size, composition and economic contribution of the different components of the informal economy, and equivalent measures of the formal economy for comparison as needed.

-

Contextualizing informality – the data, statistics, and indicators on contextual factors that impact on the size and composition of the different components of the informal economy, conditions of work, and the capacity and opportunities for people to transition to the formal economy.

Importance of the local context

While global and regional frameworks are important and efficient mechanisms for addressing common issues, national context matters. Gender norms differ between societies, and any discrimination women face in accessing education and labour market opportunities depends on local norms.

Equity in economic opportunities and decent work is an important element of gender equality, and an area where significant gaps remain. National statistical systems should support analysis of the data they collect so it is useful in shedding light on the issues most important to gender equality in the national context. This could include examining informality versus formality by sex and geographical locations, education level, household composition, number of children, economic sector, and occupation type. Also, comparing the working conditions of women and men within the informal economy assesses inequalities and gender gaps so they can be addressed.

Another important dimension is city level data. Many policies and regulations affecting informal workers are devised and implemented at the city level. To address this need, WIEGO prepares publications with city level as well as urban and national level data on informality and informal workers in its Statistical Brief series.24

The indicator framework being developed to operationalise the new standards for measuring informality will support countries in their efforts to provide national context. The framework includes dozens of indicators that can be used alone or in combination to show informality from different angles. When combined with qualitative data and research, informality statistics will be a rich source of information that will show the comparative size and nature of informality and formality and how these relates to gender equality goals.

2.3 Informality and the global priorities for gender equality

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have gender equality as a central priority, both explicitly in SDG 5 to achieve gender equality, and implicitly through the call to monitor sex-disaggregated and gender-related data on most of the other goals. Using SDG 5 as a guide to global priorities for gender equality, this section explores those most relevant to gender and informality. In addition, the United Nations Minimum Set of Gender Indicators provides guidance on priorities and statistical measures related to economic empowerment, education, health and related services, public life and decision-making, and human rights of women and girl children.25

Unpaid domestic and care work

|

|

Women doing domestic chores while taking care of her child, in the Kalulushi compound (Copperbelt Province, Zambia) (November 2015).

Photographer: Crozet M. |

The uneven distribution of unpaid informal domestic and care work is one of the biggest barriers to gender equality and to women’s economic empowerment and is closely related to issues surrounding gender and informality.26 For many, entering employment depends on being able to manage paid work with family responsibilities. Paid informal activities can be the only choice for people who face limited access to formal employment and need flexible work arrangements that allow them to work in or close to home.27

The International Labour Conference Recommendation 204 (para 21) stresses the need for action on childcare, calling for “access to affordable quality childcare and other care services in order to promote gender equality in entrepreneurship and employment opportunities and to enable transition to the formal economy”, underlining the important link between gender, informality, and care work.28 The ILO Care Report highlights major gaps in the availability and affordability of childcare and calls for sustained annual investment of 4.0% of total annual GDP to provide transformative change.29

Recognizing and valuing unpaid care and domestic work, and promoting shared responsibility for it, is the focus of SDG Target 5.4.1. There is strong international momentum around collecting improved individual-level time use data to help elucidate and address these concerns. These include the United Nations Expert Group on Innovative and Effective Ways to Collect Time-Use Statistics30, and the ILO LFS modular time use measurement project.31 Unpaid activities, such as domestic and care work, are typically informal, meaning they are not covered by formal arrangements. It is important to recognize these activities as part of the informal economy, to make them more visible and encourage measures to better protect people undertaking these forms of work.

Gender data and analysis on time spent doing paid and unpaid work and other activities is extremely valuable for understanding how gender impacts engagement in informal and formal employment.32 Time use surveys should include the questions needed to identify informality in line with the new international statistical standards to be adopted at the 21st ICLS. This will allow them to complement other data sources by identifying informal employment that might otherwise go uncounted, possibly because it is small or being done simultaneously with other forms of unpaid work. The ILO project on LFS methods for measuring time use will be providing guidance to countries on recommended approaches. Global work on time use survey methods and classifications coordinated by the United Nations Statistics Division are also supporting better data that will contribute to gender analysis of informality.

Access to economic resources

Countries are aiming to end poverty in all its forms everywhere. One indicator of progress is the percentage of women and men who have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control of land, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services.33 Access to such resources is directly related to employment opportunities and economic empowerment.

Women do not have the same degree of ownership, access and control over economic resources as do men. Although women are often disadvantaged, gender inequality is not always in one direction. In some societies, traditions require land be passed through the matrilineal line and a greater share of women own land than men.34 In other cases, even where land ownership is similar between men and women, rights to sell and/or bequeath land, tend to be concentrated among men landholders. Joint ownership can also be common for different assets. These variations highlight the importance of collecting nuanced data on the type of assets and resources women and men have access to, own and control.

Inequalities due to gender, ethnicity, age, disability, geographical location, and other factors impact financial and food security, can limit access to credit, and shape an individual’s opportunity for employment and economic gain. As an example, almost one third of employed women are in the agricultural sector, yet less than 13% of agricultural landholders are women. Despite equality in the eyes of the law in most countries, discriminatory gender norms and customary laws often prevent women from exercising their legal rights.35

Measuring informality in a meaningful way involves going beyond identifying if a job or business enterprise is formal or informal. How close or far the person or economic unit is from being formal provides more telling data for action. Whether a business or household enterprise can transition to formality may depend on the assets and capital available to grow and be sustainable. Data on asset ownership and control in the context of informal businesses is needed to support analysis of gender and informality. This should draw from the experience and recommendations of the Evidence and Data for Gender Equality (EDGE) project and the United Nations Guidelines for Producing Statistics on Asset Ownership from a Gender Perspective (2019).36 Also the work of the World Bank to measure asset ownership and control through the LSMS+ Program.

Information and communication technologies

The digital economy is transforming how we live and how we work. Data suggests mobile broadband infrastructure (3G and above) is almost universal, but accessibility varies considerably. Globally, 57% of women 62% of men are using the Internet but in the least developed countries, usage rates are low, and the gender gap is high - 19% of women compared to 31% of men use the internet.37 The different experiences of women and men, and across age groups, are hidden in average rates. Detailed data are vital to show how information and communication technologies (ICTs) are being used and where the digital divide needs attention from policymakers. For example, recent LSMS+ data show that men in Malawi and Tanzania are significantly more likely to own mobile phones than women and these gender gaps widen in rural areas.38

Empowering women through technology is an enabler for gender equality recognized by SDG Target 5.b and the associated indicator on mobile phone ownership.39 Technology is likely to play a major role in shaping the future of work, including digital platform employment. The role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in employment is highly relevant to gender and informality and has the potential to increase informal work in countries and sectors where it has not been apparent before.

Digital platform employment – online platforms like Upwork, and location-based platforms like Uber – are emerging as a way of sourcing employment. Data on the number and characteristics of people accessing employment through digital platforms is scarce but where available show this topic is highly gendered and informality is of high relevance. Improving data collection on this topic is linked to implementing ICSE-18 and the measurement of dependent contractors.

A 2018 study of digital platform workers in Ukraine, where it is estimated that at least 3% of the workforce is involved in digital platform work, surveyed 1,000 people who identified as digital platform workers.40 It found that three quarters of them were informal, much higher than the national average rate of informality (24%41). The study revealed significant gender gaps among these workers, with men on digital platforms earning 2.2 times more than women doing this kind of work. Strong occupational segregation was also evident, with IT-related work dominated by men (88%) and translation work dominated by women (74%). As digital platform work grows, gender data is going to be essential to ensure this form of work is equitable and does not perpetuate gender stereotypes.

ICT is also becoming the main means of accessing information. If gender gaps in access to ICT persist, women could be at a disadvantage in getting the information and training they need to support their economic empowerment. As governments shift services to electronic means, such as registration for social security, people who lack access to ICT, or the capacity to use it, might be left behind in efforts to transition from informal to the formal economy.

Data will be needed on the use of ICTs by those doing informal work, how the patterns of use compare between women and men, as well as to women and men with formal arrangements. Ownership of mobile phones is proving to be highly relevant measure in low- and middle-income settings where employment opportunities are increasingly dependent on mobile phones and applications. Gender data on the type and conditions of digital platform work is a priority and this has been scarce to date. Data on the accessibility and use of information and e-government services will provide context to understand the potential for transitions to and from the formal economy.

Participation and influence of women

|

|

Ms. Sunita Shrestha, manager of a handicraft production of felt objects and owner of a shop that sells them, working with some of her employees, Kathmandu (Nepal) (December 2016).

Photographer: Crozet M. |

Full participation in leadership and decision making is a key gender goal (SDG Target 5.5) needed for transformative change. In 2022, only 26% of national parliamentarians globally are women42 illustrating how much progress remains to be made. Such gender gaps are evident not only in the highest spheres of public influence but at all levels of leadership and decision-making, most likely including in micro and small enterprises in the informal economy where data collection and gender analysis are limited.

The need for women to participate and influence debate extends to issues surrounding the informal economy. Women need to be supported to participate, be counted, and be heard when it comes to data and policy decisions about informality. Progress has been gradual to date. When the International Labour Conference discussed the informal economy as a principle and explicit agenda item for the first time in 1991, the “dilemma of the informal sector” was explored with 220 speakers giving their views on the issue. Almost all supported the importance of the topic and the need for continued attention to it. Of the 220 who spoke, only nine were women (4%). This shows how few women were directly involved in that first global debate that began to shape the development agenda for informality.43 However, real progress has been made to achieve more equal representation of women in the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). At the last ICLS in 2018, women comprised 48% of participants, up from 33% in 2013. Women were also getting closer to parity among the head of ICLS delegations at 43%.44

Gender data are needed on women in management roles and as business owners in the informal sector. Data on the relationship between informal employment and participation in other forms of informal and formal work could shed light on the barriers and opportunities available to women to gain employment and to work at high levels of skill, responsibility, and earnings. Also, gender data on who is involved in developing national, regional, and international labour laws and policies is relevant for tracking the full participation of women in these processes.

The role women as contributing family workers play in decision-making, influence and control of family and household enterprises is key to classifying their work accurately in statistics. More detailed questions to test their involvement in the family enterprise could better determine the boundary between own-account workers and contributing family workers and find out how family workers are benefiting from any profits generated. Research is being done by the ILO on the classification of contributing family workers, their decent work deficits, their potential for coverage by formal arrangements, and transition to more secure forms of employment.

COVID-19 and its impact on gender and informality

COVID-19 has had a major impact on the informal economy and on women. The ILO Monitor reported that global employment declined disproportionately with women and youth being the hardest hit during 2020. Before COVID, women were around 40% of all people employed, yet they suffered nearly half (48%) of all employment losses in 2020. Youth, particularly young women, have been the most affected.45

Informality is normally thought to provide a cushion in times of crisis, but, in Brazil, the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the informal economy has been unexpectedly high. Panel data analysis revealed two thirds of the 11 million jobs lost were informal and most transitioned to inactivity rather than unemployment. Gender, racial and other inequalities were found to be worsening. Women suffered more than men and have faced more difficulty during the recovery. An emergency cash transfer system – Auxilio Emergencial – representing 9% of national GDP has been part of government efforts to provide support.46

A WIEGO study of the COVID-19 impact on informal workers in 11 cities across five regions estimates that, in April 2020, at the height of initial lockdowns, 74% of informal workers were not able to work. Government relief measures reached around 40% of the study respondents in the form of cash grants and food aid, although these were usually insufficient to cover living expenses. A historical lack of data on informal workers, complex administrative procedures, and limited access to digital technologies were among the barriers to rolling out and accessing relief.

The study predicts that recovery will be slow with restrictions to work ongoing and average weekly hours and earnings below pre-COVID levels.47

In a case study conducted in Indonesia on leveraging digitalization to cope with COVID-19, UN Women and UN Pulse Jakarta concludes that digitalization is not helping all types of businesses equally: the sex of the owner, the status of the business as formal or informal, the age of the business and whether the business is growth-oriented or necessity-based all play a role. The findings show that women and men are coping differently: men owners of Micro and Small Businesses (MSBs) are more likely to apply a wider range of strategies to combat revenue loss, with greater access to finance and assets compared to women. This can also be explained by overrepresentation of women in informal businesses, which is a key barrier to access financing and social protection: most women owned MSBs do not benefit from government stimulus plans. As a result, informal women-owned MSBs, many of which were established during the first two waves of COVID-19 are disproportionately turning to digitalization as a business coping strategy.

Analysis of the informal economy in China, based on digital payment transaction data (more than 80% of adults use digital payments in China) shows the decline in informal micro-businesses during the pandemic and that women operators were harder hit than men.

Data on 80 million informal offline micro-businesses – mainly in the services sector and unable to work from home – indicate that both the number of active merchants and the value of sales had declined by half by February 2020 and were back to around 80% of pre-COVID levels by April. The number of women-led micro businesses fell by 53% and sales turnover by 57%. This was 5 and 9 percentage points higher than the averages for male-led businesses.48

The State of Working India 2021 report focused on one year of COVID-19. It used panel data to study the transitions that have occurred between different forms of employment in India during the pandemic. It found there has been a “massive exit” of workers from permanent salaried jobs during the pandemic, nearly half of whom moved to informal work. Gender analysis shows that it is mainly men who have moved into informal employment while nearly half of all women in the workforce withdrew completely during 2020 (compared to 11% of men). 49

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on unpaid domestic and care work, mainly undertaken by women. Before the pandemic, women did almost three times the amount of this work than men. UN-Women Rapid Gender Assessment Surveys (RGAs), launched at the onset of the pandemic, show that school closures and amplified healthcare demands during the pandemic are dramatically increasing the burden on women and limiting their employment opportunities – informal and formal50 and, more worryingly, pushing women out of labour market. 51

Measurement challenges and data gaps

Standards for producing statistics on the informal economy have been evolving since the early 1980’s when the 13th International Conference of Labour Statisticians first passed a resolution encouraging countries to measure the informal sector. The first global standards were introduced a decade later when the 15th ICLS debated the issue in detail and adopted a resolution on statistics of employment in the informal sector.52 The global standards for the System of National Accounts (SNA) were revised in the same year. The new version of the SNA recognized the ILO’s lead role in defining and measuring the informal sector and integrated the ICLS resolution into SNA 1993, aligning standards for economic and labour force statistics which have some considerable overlaps.53 The most recent change to the standards was in 2003, when the 17th ICLS adopted a statistical definition of informal employment. It recognized that informality exists outside the informal sector, which was an important development.54

The early informality statistics standards provided definitions of the informal sector and informal employment, enabling countries to start measuring these concepts. As capacities and experiences in measuring informality have increased, definitions have been refined and the statistical community is in a good position to agree on more harmonized methodologies that respond to the latest needs for gender data.

The civil society organization, Women in Informal Employment: Globalising and Organizing (WIEGO), is a leader in the work on improving gender data on informality. Their statistical work points to where the greatest challenges have been and where achievements have been made. WIEGO has focused on promoting gender-sensitive concepts and statistical standards, advocating for informality to be mainstreamed in labour statistics and economic statistics, and supporting the production and dissemination of informality statistics that are accessible for researchers, policymakers, and advocates.55

A major challenge for informality statistics has been that its measurement is not universal or regular. Attempts to aggregate national data at a global level show how much progress has been made and how much remains. In 2002, the ILO and WIEGO worked together to publish global analysis of informal employment data for the first time. At that point, informality statistics were only available from 25 countries.56 Just over 15 years later in 2018, an ILO assessment of data availability found that 67 countries had produced direct measures of informality within the last ten years.57 Despite persistent data gaps, there has been sufficient data to produce global and disaggregated estimates of informality, which has been an important advance for evidence-driven policymaking. In the ILO’s most recent publication on informality statistics data from 119 countries provided the basis for global estimates.58 Today, in 2022, ILOSTAT – the leading source of labour statistics – has data on unemployment for 219 countries (SDG indicator 8.5.2) but only 97 countries for the informal employment rate by sex (SDG indicator 8.3.1).59

There is extensive evidence that women’s work in the informal economy is underestimated in statistics and that survey methodologies need revisiting.60 The role of women in the home compared to other family members can lead to them being underrepresented in official labour statistics. Any employment activities they engage in could be overshadowed by domestic responsibilities and go unreported if questions are not well-designed to catch the work done by women and girls for pay or profit.61

The ILO continually maintains a generic labour force survey questionnaire (PAPI and CAPI) that provides model questions and guidance on variable derivation to produce statistics on the labour force and other forms of work. Together with a range of tools and guidance on LFS methodology, these exist to support implementation of statistical standards and the production of high-quality data at national level.62 The generic questionnaire and LFS resources will be enhanced as part of this project to recommend additional questions and methods for analysis to support better gender data on informality.

In summary, there are general challenges for gender and informality statistics that reflect where continued and renewed work is needed. These include support for regular national labour force surveys that include questions on informality. Also, support for national implementation of statistical standards and classifications, including ICSE-18 and the 19th ICLS resolution on measuring work and its narrower definition of employment. Importantly, data producers need to undertake and strengthen the gender analysis of LFS data on the size and nature of informality versus formality and the regular dissemination of data in accessible formats.

More specific gaps and challenges in measuring gender and informality are outlined below.

3.1 Status in employment

The identification of informal employment is based on status in employment according to the International Classification for Status in Employment (ICSE). The criteria to determine if employers and own-account workers are covered by formal arrangements (registration of their business or recordkeeping for taxation purposes) differ from the criteria used to classify employees as informal versus formal (employer contributions to social security, access to paid annual leave and access to paid leave).63

Contributing family workers, who are mostly women (63% in 2020),64 are currently classified as informal by default without any specific test being applied.65 There are several issues to consider. One is the inherent gender bias in the initial identification of contributing family workers. Most countries classify wives as contributing family workers without asking about their role in decision-making for the business.66 This and other information could see them reclassified as own-account workers. There are recommendations to ask more detail about their day-to-day role in the business, use of earnings, and the frequency of their involvement to clarify how vulnerable or empowered contributing family workers are.67

Dependent contractors are a new status in employment introduced with the International Classification for Status in Employment adopted in 2018 (ICSE-18).68 This is a type of non-standard employment that falls somewhere between being own-account self-employed and being an employee. Dependent contractors are people who have a commercial agreement but are economically and/or operationally dependent on a client or intermediary, which exercises control over their work or access to the market. The inclusion of this concept in statistical standards responds to data needs for monitoring the growing number of people in these kinds of work relationships. It also responds to the need to better identify the working arrangements of the traditional home-based and industrial workers, such as piece rate workers working in value chains. Implementing ICSE-18 will provide countries with extremely valuable data on trends within informal employment, both through the classification of status in employment and analysis of cross-cutting variables like place of work, occupation, and industry. Implementing ICSE-18 likely will also affect the classification of some home-based workers and other workers currently classified as own-account self-employed.

3.2 Place of work

|

|

Improvised hairdressing salon in Columbia (2007). Photographer: Lord R. |

A question on place of work is essential for identifying priority groups such as home-based workers, domestic workers, and street vendors – priority groups for gender and informality identified through the work of WIEGO. Used in combination with information on industry, occupation, and status in employment (particularly ICSE-18), a well-designed question on place of work enables identification of these types of workers and provides the basis for comparing their employment conditions within and across groups of workers.69 Place of work is an essential cross-cutting variable for the compilation of coherent statistics on work relationships in ICSE-18.70

Place of work is a gendered element of employment and there can be gender-related vulnerabilities associated with some types of workplaces over others. Analysis by WIEGO in Bangladesh and Nepal found that home-based work represents a greater share of employment for women than for men.71 Such data are needed to reveal important differences between women or men. This was relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic where some forms of work were more easily adapted to being done at home and those working outside the home may have been exposed to greater health risks.

The generic LFS developed by the ILO includes a question on place of work, but not all countries include such a question in their labour force survey. It is also not standard for some other major household surveys (e.g., Demographic and Health Surveys) to include this question when asking about employment-related characteristics, limiting the utility of the resulting datasets to identify types of workers and analyse their characteristics and working conditions.

3.3 Coverage of labour force surveys and choice of respondent(s)

Traditional labour force surveys are conducted using households as the point of entry. People who live in unlisted dwellings (e.g., some informal settlements, dumpsite residents, homeless or street dwelling people) and in institutions (e.g., hospitals, boarding schools, army barracks) are excluded from household surveys and so are not represented in the statistics. This may include waste-pickers, a priority group for gender and informality, who tend to be mobile, work seasonally, and may avoid survey researchers for fear of public authorities. Those who live on the street or at the dump site will be excluded from regular household surveys.72 The difficulties reaching this group is apparent in forthcoming analysis of data from Senegal. In Dakar, the number of people working as waste-pickers is known to be high, but very few were found among respondents to the LFS, limiting analysis of their situation.73

For the households that are included in surveys, it is a challenge to collect data from everyone directly. When interviewing all household members individually is not practical, the survey enumerators typically interview a member of the household who is best placed to answer on behalf of themselves and others who reside there. Reporting by the head of household or most knowledgeable person about the work other household members (i.e., proxy reporting) has been shown to introduce gender bias to data collection. For instance, in settings where paid work for women goes against gender norms, their employment is underreported. Proxy reporting is commonplace in labour force and other household surveys where it is not always feasible to interview all members of the household directly about their activities. However, proxy interviewing is known to have implications for data quality, particularly for some topics, for example earnings, asset ownership etc. As such this should be borne in mind in designing survey protocols and the questionnaire itself, as well as during the analysis stage, both to try to assure data quality and interpret results appropriately.

Opportunities for integrating gender in informality statistics

The ILO is committed to achieving gender equality and integrating gender across all areas of its work. With clear mandates from the ICLS, the Department of Statistics has a strong gender data focus in its methodological and analytical work. Following the adoption of a checklist of good practices for mainstreaming gender in labour statistics in 2003, the adoption of the 19th ICLS Resolution on measuring all forms of work in 2013 was an important milestone for gender data.

The ILO’s current work is focused on supporting implementation of the 19th ICLS, developing modular approaches to measuring time use, and on engendering informality statistics. Methodological work on measuring volunteer work and measuring violence and harassment at work is also contributing to filling important gender data gaps. The analysis and dissemination of gender data is an ongoing priority and new gender-disaggregated data is regularly released through ILOSTAT.

The revision of standards is a valuable opportunity to continue the work on integrating gender in labour statistics. New measures of informality provide an entry point to advocate for more and better gender data and analysis of the topic. The chance to review and clarify gender data needs and to ensure they are considered in the redesign of questions and methods for measuring informality. A new comprehensive and gender-sensitive indicator framework will guide countries on the range of statistics that could be produced, analyzed, and used. This provides a catalyst to advocate for better gender data and embed the regular production of informality statistics in national statistical programs.

The standards will add dependent contractors to informality statistics and possibly extend the measurement of informality to other forms of work, an opportunity for statistics to demonstrate responsiveness to changes in the world of work. The revision and adoption of new standards allows the ILO and partners to anticipate the technical assistance and capacity building needs at the national level and start planning for how those needs can be met. This fits with the ILO’s longer-term strategy to provide coherent guidance and tools to improve measurement of women and men’s work so that gender data gaps can be systematically and sustainably filled.

4.1 Growing gender data needs

Revising the standards for measuring informality – something that occurs infrequently – needs to consider existing demands and anticipate what could be needed in the future. There is a clear demand to produce and use sex-disaggregated data and to work in partnership to combine quantitative and qualitative research methods. Collective wisdom on measuring and monitoring informality suggests priorities for future research will include the impact of migration, urbanization, and climate change on informal employment. Also, how demographic change, economic growth and the focus on formalization are playing a role in the extent and nature of informality. Digitalization and the evolution of the digital economy is also likely to have an impact on informal employment and generate new data needs. Analysis and research are needed not only on the size and characteristics of informality, but also the contribution it makes to national economies and measures of economic performance, such as the GDP.74

There is a strong demand for engendered informality statistics and gender analysis. Labour force surveys can be enhanced to explore topics to better understand and contextualize gender and informality, including access to and control of economic resources, the use of ICT in business, and the business-related earnings and costs of micro and small businesses.

Questions tailored to explore the influence of gender norms, such as on barriers to employment, motivations for running an informal business, and plans for its future can shed light on how such norms are impacting economic empowerment. For example, research on measuring women’s rural employment suggest questions on time/distance for travel, norms around gender and employment, land and asset ownership, length of time available for paid work versus unpaid care and domestic work, and skill development, would provide valuable gender data.75 If included in labour force surveys, it would be possible to compare data on these issues between informal workers and formal workers, as well as across other socio-demographic characteristics.

4.2 Changes to how informality is measured

|

|

Volunteer of the association for hospital schooling providing learning support in France (2002).

Photographer: Deloche P. |

Integrating gender in statistics involves eliminating bias in data collection and production that influence the relevance and accuracy of statistics for women versus men. This includes definitions of statistical concepts and the framing of labour force survey questions. Engendering the process involves considering how these apply to women and men, how bias might occur and how that should be prevented.

Informality refers to any work or enterprise not sufficiently covered by formal arrangements. Formal arrangements differ from country to country, so the aim of the standards is to agree on approaches that will provide internationally comparable data while respecting the importance of national context and adaptation. The new standards for measuring informality will build on established country practices to recommend the most effective generic solution for identifying informality and formality.

The standards will support measurement of the informal market economy from the perspective of enterprises (informal sector) and individuals (informal employment). The broader ‘informal economy’ remains relevant, going beyond market-oriented production to include own-use production, volunteering, and unpaid trainee work.

Significant changes being considered for introduction in the standards are:

-

The expansion of the boundaries of the informal economy to potentially incorporate all forms of work, including own-use provision of services.

-

Informal enterprises producing ‘for the market’ to include units where goods or services are ‘mainly’ produced for pay or profit (to align with the 19th ICLS standards). Currently the threshold for market production and inclusion in employment is set at ‘some’ goods and services produced for the market. Consequently, some units previously identified as household market enterprises (and within the informal sector if they were informal) would be identified as own-use producing units for which statistics could be separately compiled.

-

Contributing family workers no longer classified as informal by default (could instead depend on whether formal arrangements are available in the country and, if so, whether they are accessed by the contributing family worker).

-

Remove the current option to exclude agriculture from the measurement of the informal sector. The agriculture sector is already included in informality statistics by some countries and in the ILO estimates of informal employment.

-

More specificity around the operational criteria for identifying informal employment and informal enterprises.

These changes have implications for the measurement of women and work, particularly the threshold for market production and subsequent inclusion of informal enterprises in employment, and the option to classify contributing family workers as formal if they are covered by formal arrangements.

Defining informality for dependent contractors

The introduction of a new status in employment at the 20th ICLS in 2018 was an important milestone in recognizing the growing number of people who are classified as self-employed but depend on one client, company, or platform for most of their work. Referred to as dependent contractors, one objective of revising the standards is to decide what determines formality and informality for this new group.

The ILO working group has made good progress in working out how to determine informality for dependent contractors. The following criteria have been identified as relevant for defining the informal sector and informal jobs for this group:

-

registration of the economic unit (informal or formal economic unit);

-

tax registration: either by the dependent contractor or by/through the economic unit on which they depend;

-

registration for statutory job-related social insurance: either by the dependent contractor or by/through the economic unit on which they depend.

More discussions will be undertaken to determine the exact nature and combination of criteria.

Contributing family workers

An important change being considered by the working group is whether contributing family workers, currently classified informal by default in the statistics, should have the option of being classified in formal jobs. While formal arrangements are not available to contributing family workers in most countries, it is likely most will remain classified as informal. Providing for the possibility to be classified as formal, based on relevant criteria, responds to the situation of countries that are extending formal arrangements to this group. For example, one part of the criteria for classifying contributing family workers as formal could be if they are carrying out work for a formal economic unit – one that is recognized by law as being a separate legal entity from their owners, keeps accounts for tax purposes, and is registered in the national system for tax registration and social insurance – as is done in 1-2-3 surveys. This could provide more disaggregated statistics on the potential for formal arrangements for contributing family workers, of whom almost two thirds (63%) were women in 2020.76

Beyond the formality or informality of the business or other economic unit they work in, access to social protection for contributing family workers, such a job-related pension schemes or health insurance, is a key issue. Recommendation 204 on the transition to the formal economy calls on countries to gradually extend social security, maternity protection, and other decent working conditions to all workers in the informal economy (para. 18). Informality statistics should play a role in identifying if and where such arrangements are available to contributing family workers and monitor any transitions to formality as can be done for other self-employed and dependent workers. In the case of individuals in vulnerable employment, monitoring the process of formalization would also entail complementary statistics on any decent work deficits, as well as gainful employment opportunities schemes.

Formal arrangements for contributing family workers currently exist in few but a growing number of countries. Costa Rica and Cabo Verde have updated national laws to support the participation of self-employed workers in pension and/or health insurance schemes. Argentina, Brazil, Cabo Verde, Jordan, Kenya, Mexico, the Philippines, and Uruguay, include the self-employed in their general social protection schemes. There are also targeted schemes, such as social insurance for self-employed workers and their dependents in the Dominican Republic, which has covered 60,000 workers since its establishment in 2005.77

There are challenges in extending formal arrangements to contributing family and own-account workers. Self-employed people in household market enterprises that have low turnover or seasonal income, may not be able to afford or make regular contributions to social protection schemes.78 Concerns have been raised that allowing the possibility for contributing family workers to have formal jobs will distract from the broader goal of shifting them to less vulnerable forms of employment.79 While this policy objective still is highly relevant, allowing the possibility for contributing family workers to have formal jobs ensures that informality statistics can respond to countries attempting to extend formal arrangement to vulnerable workers.

Extending informality to all forms of work

The ILO working group has also generally agreed on the need to extend conceptualization of informality and formality to forms of work other than employment, including own-use production of goods and services, volunteer work, and unpaid trainee work. This is a significant development for gender data and for the measurement of informality. Some unpaid forms of work, such as own-use production of goods and unpaid trainee work, were included in the previous definition of informal employment but not explicitly addressed. That these types of work activities are going to be integrated in the framework is an important recognition that much of the work carried out by women in relation to unpaid care work, for example, is informal. It also acknowledges the possibility that at least part of these types of activities could be covered by formal arrangements if the policy objective exists in a country.

Extending informality to all forms of work will facilitate measurement and analysis of informal and formal work across domains. For example, care work takes place across all forms of work (employment, volunteer work, own-use provision of services, unpaid trainee work, and other unpaid work) and in both the formal and informal market economy. Including data on employment in care work (personal carers, etc.) along with unpaid work through own-use provision of services, volunteering, and unpaid trainee work, can provide a better picture of the organization of care work within society, and support more holistic policymaking.

The new standards are unlikely to provide detailed operational definitions of informality in relation to all the different unpaid forms of work. However, the change can be viewed as an important first step for how informality relates to these types of activities in the statistics. It points at the importance and the possibility for collecting data on measures that are aiming to extend the protections offered by formal arrangements to people working in a wider range of productive activities.

4.3 New indicators and statistical products to respond to data needs

|

|

Human resources development and employment centre in Tianjin, China (August 2007).

Photographer: Crozet M. |

Gaps in informality statistics are not limited to data collection and methodological issues. Making good use of data that is already available is also a priority. There is a need for more work on translating gender data on informality into actionable information that policy and decision-makers can use. To that end, the ILO Working Group on the Revision of Statistical Standards on Informality has drafted an indicator framework that, when implemented by countries, will provide a rich source of statistics ready to apply in the policymaking process.

There are more than 100 proposed indicators grouped under five dimensions:

-

-

extent of informality (e.g., level of informality, transitions between informal, unemployment and outside the labour force);

-

structure of informality (e.g., industries, occupations, size of informal sector enterprises);

-

decent work deficits (e.g., earnings, hours of work, form of remuneration);

-

contextual vulnerability (e.g. number of informal workers per household, social protection coverage, and the relationship between informality, poverty and income security);

-

other (mainly structural drivers of informality).

-

When produced and disaggregated, the indicators could provide comprehensive statistics about informality. The framework is intended to guide data producers and users on what measures could be relevant and useful. Decisions on which ones to select will depend on the context, available data sources and resources, and could vary depending on priorities. The question sequences to collect the needed data must be manageable and minimize respondent burden, something which is being considered in the ILOs questionnaire development and testing work.

A set of core indicators recommended for regular production will be explicit in the resolution on the new standards. It will be essential to make sure these have a strong gender dimension. Furthermore, guidance and technical assistance to disaggregate, analyse and communicate data is needed to support gender-sensitive policymaking and should be part of the broader indicator framework.

UN Women have provided inputs to ensure the framework responds to needs for gender data. Their suggestions include explicitly disaggregating all indicators by sex as well as the combined disaggregation of some indicators to better account for intersectionality. Furthermore, enterprise-related indicators disaggregated both by sex of owner and size of enterprise (e.g. number of employees and/or amount of output/sales) to reflect needs for policy formulation and monitor policy impact. Priority indicators from a gender perspective are being identified.

4.4 The role of technical assistance and capacity development

The ILO provides technical assistance and capacity development to support national statistical systems to produce statistics through labour force surveys. This includes research and development of methodologies, advocating for regular labour force surveys, providing advice to align national data collection with international standards, and supporting the analysis, dissemination and communication of data collected through the LFS and labour market information systems.

After the revised standards are adopted by the ICLS, their implementation at national level will be gradual. For example, how the standards are being applied in data collection, production and analysis of informality statistics will need to be explained to data users by national statisticians. One way to support this transition and explain any breaks in series is to produce informality statistics using both the old and new standards. This can help to illustrate how new measures impact the data versus actual changes in rates and nature of informality.

Revised standards, the associated indicator framework and accompanying tools will provide a strong basis to improve the quality of informality statistics. However, data quality ultimately depends on the national statistical systems that collect and produce it. The ILO and the international statistical community will need to support the implementation of the new standards (in combination with other standards and classifications that guide measurement of the labour force and all forms of work).

The new standards will be an opportunity to encourage countries that do not measure informal employment to start doing so. And for those countries already producing these data, it will provide opportunities to expand their work and use the new conceptual framework to better measure and quantify informality.

4.5 Summary and next steps