A global fund for social protection

Lessons from the diverse experiences of global health, agriculture and climate funds

Abstract

The recent social, ecological and economic crises have not only revealed the gaps in social protection systems across the world, but also drawn global attention to the ways in which international financial architectures have failed to support the development of universal social protection systems and floors. Within this context, this paper examines the idea of a global fund for social protection (GFSP) which has emerged as a potential solution to these structural failings. By drawing on the experiences of seven global funds across the health, climate, and agriculture sectors, the aim of this working paper is to identify key lessons that can guide the possible implementation of a prospective GFSP. Through a careful analysis of the governance structures, norms and standards of these funds, the paper makes certain recommendations to be taken into consideration if a GFSP is to be developed and implemented in the future.

Executive summary

Context

The idea of a global fund for social protection (GFSP) has taken hold over the last decade as a potential solution to structural gaps in the global financial and development architectures that have failed to ensure that social protection receives an equitable share of development resources available and have left 4.14 billion people – or 53.1 per cent of the world’s population and especially those in low- and middle-income countries – excluded from any social protection scheme (UN 2021a). There is no single proposed model for such a fund, but there is a need for clear, strategic thinking about the prospective governance structures and mechanisms overseeing a putative new fund.1

Research aims and focus

This study aims to understand the experiences of setting up global funds across the health, climate and agriculture sectors and identify lessons to be learned from them that can guide further thinking about the implementation of a prospective GFSP. It focuses on the institutional governance arrangements for seven global funds carefully selected for their diversity in terms of origins, longevity, aims and institutional structures.

Governance is a crucial element of the successful implementation of a prospective GFSP. Such arrangements, as they are instituted, condition the donor-recipient relationship, including the power dynamics between them, their respective roles and relationships, the “rules” of decision-making and accountability. Careful design of the governance structure and clear reference to the norms and standards it works to are vital for all stakeholders and essential to the effectiveness of the fund. This, in turn, is needed for long-term commitment to and country ownership of a prospective fund and, ultimately, the successful realization of its goals and the building of universal social protection systems, including floors.

Analytical framework

The paper uses a conceptual framework for analysing the governance arrangements of the global funds selected. This comprises five key elements:

-

organizational and institutional structures of the fund;

-

in-country stakeholder engagement, country ownership and coordination with national authorities and donors;

-

resource mobilization and the development of affordable and sustainable financing;

-

quality of investment and alignment with human rights and international labour standards; and

-

a strong focus on data, results, learning and innovation.

Lessons

-

-

There are risks to creating a new global fund. These include it being under-resourced, that it facilitates the fragmentation of development financing, that private-sector sources of finance exercise a disproportionate influence and undermine the norm-setting functions of established intergovernmental organizations, and that country ownership is insufficient to mobilize commitment from low-income-country recipient governments.

-

A putative GFSP would require strong advocates, including high-level political support, non-state actors and donors that are willing to commit funds and sustain this commitment over time in the interests of building enduring alliances to support the development of universal national social protection systems, including floors.

-

Graduation from international financing in a way that is synced with countries’ economic development (and not just their existing level of need) is effective when there are robust and flexible transition support policies working with governments from the outset.

-

There is a need for utmost caution about promises of significant amounts of new money implicit in the terms “innovative financing mechanism” and “catalytic investments” as well as of the likely contributions by the private (commercial) sector to the fund’s finances. Such sources tend to deliver less finance in practice than is heralded and often come with “strings” attached.

-

Private sources of finance can make substantial new funds available, but the involvement of private entities in fund governance structures can undermine accountability and global norms. Great care is needed to ensure that ethical and vested interest concerns and due diligence are soundly anchored in governance structures and processes to avoid this.

-

Embedding robust environmental, social and governance norms and standards into a fund’s investment strategy is essential for the political legitimacy, social acceptability and operational effectiveness of a global fund.

-

The full involvement of diverse representatives – government (including ministries of social security, employment, health and finance), social partners and other civil society groups (such as users and beneficiaries) – from countries from the global South in global-level deliberations about a prospective global fund is crucial for the fund’s legitimacy and the “buy-in” of recipient countries, including in the mobilization of domestic resources.

-

Inclusive, pro-equality and participatory governance and operating models that have a proven track record of “reaching out” to marginalized and minoritized groups are critically important to the success of global funds.

-

Stakeholder engagement policies and plans adequately resourced to support substantial and meaningful participation of governments, social partners and civil society in the governance structures and processes of global funds are essential. Voting rights at all levels of a fund’s governance, including on the fund’s board, strengthen country ownership.

-

Global funds that are experienced by Southern countries as yet another form of donor-driven charitable aid are unlikely to enjoy the legitimacy necessary for sustained country ownership and stakeholder interest.

-

Recommendations

-

-

A GFSP should be clearly based upon an explicit rights-based approach to social protection, anchored in human rights instruments and international labour standards. An intersectional approach to gender and social equality, addressing multiple axes of disadvantage and discrimination to ensure inclusiveness, is integral to this.

-

Setting benchmarks for robust monitoring and outcomes-based learning systems, anchored in human rights and labour standards, which are fully accessible and inclusive of multiple stakeholders, would shore up accountability, inclusion, legitimacy and effectiveness, and help overcome key collective action problems.

-

Social partners and other globally representative civil society organizations should be full and equal members of deliberative processes around the shape, size and governance structure of a prospective GFSP. Parity of esteem, representation, influence and accountability between Southern and Northern actors should be a fundamental principle from the outset.

-

UN processes around a prospective GFSP should be made inclusive. Use of relevant international forums, committees and processes outside the UN system may also give excluded voices direct access to deliberative and decision-making processes about a prospective GFSP.

-

Attention should be paid to the potential for international initiatives on taxation to increase the funds available for a GFSP. This includes initiatives to prevent the erosion of national taxation capacity and to increase the fair distribution of national tax revenue, such as ensuring that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) benefits low and middle-income countries, as well as action to reduce illicit financial flows. However, serious consideration should also be given to the further development of international forms of taxation to provide core funding for a GFSP, particularly an international financial transactions tax, a global wealth tax and a carbon tax, as well as to making climate change finance available for social protection systems, including floors.

-

A GFSP could support countries in strengthening their domestic financing strategies, including through mechanisms such as the further development of taxation of public “bads” (tobacco and alcohol products, unhealthy foods and beverages, excess wealth). Climate-related taxation such as carbon taxes could also help support countries to develop climate adaptation-oriented social protection systems, including floors. Such taxes are nevertheless most effective when levied at a larger, preferably global, scale.

-

Seeking funding from the private sector, including philanthropic foundations, may increase the flow of funds available for social protection. However, this in no way implies that such entities should be able to tie those funds to particular sorts of interventions or have a role within the governance mechanisms of a GFSP. The relationship between the fund and private donors and participants should clearly be set out in principled form in the governance framework from the outset, as should ethical safeguards.

-

Where innovative forms of financing and partnerships with private actors are utilized, a commitment to not invest in products, services or practices that violate the principles of the UN Global Compact that commits signatories to avoiding investments and practices that violate human rights and, more broadly, the principles laid down in human rights instruments and international labour standards, and a requirement for any and all private-sector partners to join the Compact and adhere to its principles, could help to ensure that basic human rights and labour standards are protected. Any and all private-sector partners should be required to meaningfully promote access to adequate social security for all of their employees, including workers in their supply chains.

-

An independent global-level monitoring body would strengthen the requirement for transparency and accountability, as well as for effective learning and feedback mechanisms. Associations of workers and employers, and other key stakeholders such as governments, user groups and independent experts, should be full members of the body.

-

Open and widely-accessible board meetings and robust monitoring and evaluation systems would further enhance transparency and accountability, and strengthen the legitimacy and collective ownership of the fund necessary for its sustainability.

-

Meaningful and effective country ownership and commitment by all stakeholders is crucial to the success of the fund. Low-income countries should have a key role in the fund’s governance structures, and on at least an equal basis with high- and middle-income countries, and preferably with greater representation of low-income countries than of high- and middle-income countries.

-

GFSP finance should be allocated to countries on the basis of need and commitment to the principles and objectives of a GFSP. International financial support to strengthen social protection systems, including floors, is more likely to be acceptable if presented and perceived as sound domestic social and economic policy and as a solidaristic form of global public investment, rather than as international donor-driven development aid and charity.

-

Country ownership can be further enhanced by minimizing the use of explicit or implicit conditionality attached to funding awards. This could, for example, mean eschewing the use of conditionality for GFSP finance allocation beyond what is strictly necessary for financial diligence, accountability, adherence to human rights and labour standards, the principles of aid effectiveness and proven additionality of spending on social protection.

-

Notwithstanding the above recommendations, a GFSP should operate on the understanding that recipient low-income-country governments are committed to progressively building their own social protection systems and mobilizing necessary resources for these over time.

-

Further consideration should be given to the way recipient countries would access a GFSP. In this, significant weight should be given to the positive experiences and preferences of Southern countries for a direct-access model of allocating finance (whereby a recipient country’s national institutions can access GFSP finance directly from the fund or can assign an implementing entity of their own choosing).

-

We make no recommendation as to whether a GFSP should be established as a stand-alone fund or attached to an intergovernmental organization. However, the political legitimacy and acceptability of the intergovernmental organization among prospective recipient countries and its commitment to a rights-based approach to social protection and labour standards should be decisive factors in any decision as to which intergovernmental organization a prospective fund should be attached to.

-

Introduction

The lived experience of destructive waves of social, ecological and economic crisis reverberating across territories and populations have been accompanied by louder, more insistent, demands for greater global solidarity in tackling global “bads”, including poverty and inequality. The global financial crisis (2007–09) and the outbreak of the pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in 2019–20 revealed the depth and extent of gaps in social protection systems and, crucially, prompted renewed calls and initiatives to support the fiscal efforts of individual countries with very limited domestic mobilization capacities to build social protection systems, including floors, for their populations. Such demands have drawn attention to the way international financial architectures have failed to systematically support the development of universal social protection systems, including floors, particularly for the poorest countries and populations. They have also called for global responsibility to be more thoroughly enacted in the social protection field. At the height of the global financial crisis, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) emphasized the extraterritorial obligations inherent in implementing the right to social security, and stated that: “States parties should facilitate the realization of the right to social security in other countries, for example through provision of economic and technical assistance. … Economically developed States parties have a special responsibility for … assisting the developing countries in this regard” (CESCR 2008, para. 55).

One concrete expression of this confluence of solidarity and responsibility for closing the yawning social protection gaps is the idea of a GFSP. This idea has a long history, having been mooted by several experts and institutions following the global financial crisis (2007–09). Since then, its development has been spurred on by the adoption of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202)

A global fund is a generic term for a multilateral financing mechanism although, it has to be emphasized, there is no single prevailing model for such a fund or mechanism. The overall aim is to pump-prime domestic efforts to put a system, or floor, in place, helping to scale up resources and impact, by attracting (“crowding-in”) additional funds. Such a fund can also have a demonstration effect, acting as a catalyst by generating evidence for the value and effectiveness of social protection measures, thus building support and capacity for such measures from national policymakers. Proponents of a GFSP see the added value of a dedicated multilateral social protection financing mechanism as increasing the predictability of external resource flows, compared with a situation where each partner provides its own budget support and concessional financing. For some, a GFSP would also provide some degree of stabilization, supporting highly resource-constrained recipient countries in guaranteeing their populations the right to social security despite unforeseen covariate shocks (such as wars, pandemics and natural disasters). However, there is also a danger that such funding can have unintended effects. If, for example, recipient governments assume that funding for social protection will come from external sources they may be incentivized to shift their limited resources to policy areas that are of lower interest to donors.

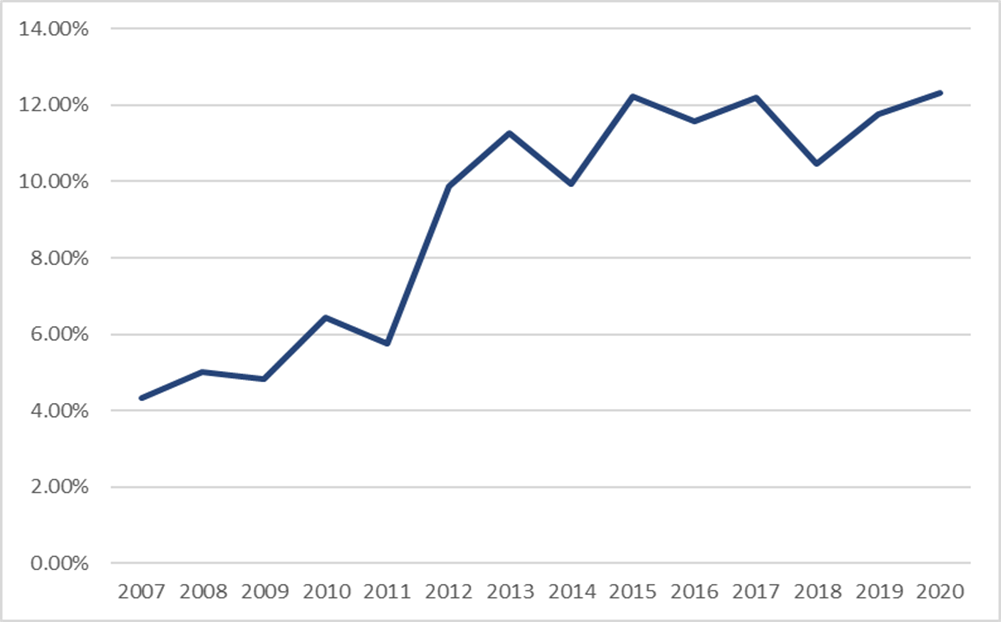

There is, on the face of it, evidence for looking at existing global funds as a potential model for a prospective GFSP. One factor is that they command an increasing share of development aid. According to

Figure I.1. Country-programmable aid of key global funds, 2007–20 (millions US$)

Note: The figure maps four climate funds (Adaptation Fund (AF), Climate Investment Funds, the GFATM and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance) and a rural development fund (International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)). A total is also provided.

Source:

Figure I.2. Country-programmable aid of key global funds as percentage of total, 2007–20

Note: The figure aggregates data for the same global funds as figure I.1. Thus: four climate funds (AF, climate investment funds, Global Environment Facility (GEF), GCF), two health funds (GFATM, Gavi) and a rural development fund (IFAD).

Source:

Many of this new generation of vertical funds emerged in response to specific global challenges. Prominent examples include the GFATM, Gavi, IFAD, the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program and the Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents (GFF), as well as a wide range of climate funds. They are highly diverse in terms of longevity, aims, institutional structure and achievements and provide a wealth of experience and a rich body of evidence on which ongoing discussions about a prospective GFSP can usefully draw.

Against this background, the main aim of the present report is to identify the experiences of diverse global funds and harvest lessons from these experiences. Our focus lies squarely on the governance aspects of the funds and is underpinned by original research into the experiences of seven global health, agricultural and climate funds, specifically, GFATM, Gavi, GFF, IFAD, GEF and the closely related Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and Special Climate Change Fund, Green Climate Fund (GCF) and AF.4

The report aims to inform ongoing deliberations in the ILO and beyond on the feasibility of such an international financing mechanism to complement and support national domestic resource utilization and mobilization efforts in building universal social protection systems, including floors, by 2030.5 Thus, bringing together information concerning global funds’ governance arrangements and how they have worked in practice enables us to contribute to developing concrete proposals on this critical aspect of the implementation of a prospective international financing mechanism. This report reviews the experiences of a selection of extant global funds in this regard and considers the implications of these experiences for a prospective GFSP. It analyses the institutional and governance structures of the existing funds with a view to better understanding the governance arrangements that may work well for a prospective GFSP.

The report is organized into six principal chapters, including this brief introduction. Chapter 1 briefly elaborates the idea and rationale for a new international financing facility for social protection and key questions to be addressed. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the research methods of the study, including the basis on which we selected global funds for in-depth study and our data sources. Chapter 3 presents a thumbnail portrait of the principal features of the global funds selected for the study, drawing out their similarities and differences together with key issues and challenges they have faced. Chapter 4 presents the findings of the study with regard to five thematic areas that comprise our conceptual and analytical framework. Chapter 5 discusses the issues raised by our findings, draws conclusions and makes recommendations to inform the ongoing discussion.

Ideational and institutional landscapes of a global fund for social protection: origins, potential and key issues

Introduction

This chapter reviews the context of this study and sets out the research questions guiding it. This includes tracing key ideational contours of the concept, as well as institutional milestones in the evolving global policy landscape on social protection. The principal constraints on developing countries’ own efforts to mobilize resources for social protection and the potential of a GFSP to bridge social protection financing gaps are reviewed. We raise questions about the governance of a potential GFSP and set out the conceptual framework that provides the structure for this study.

The idea of a GFSP

The idea of a dedicated GFSP entered the global policy arena with the publication of Underwriting the Poor: A Global Fund for Social Protection by the then UN rapporteurs on, respectively, extreme poverty and human rights, and the right to food

One issue is insufficient levels of resources to invest in developing social protection systems and floors relative to economic capacity. Currently, a dozen low-income countries would have to spend more than 10 per cent of their gross domestic product (GDP) to close their social protection floor gap

The second issue is that such countries are unable to withstand the disruptive effects of major shocks to the system – for example, major conflict and war, economic crisis, pandemic, natural disaster or climate disaster – leading to a sudden and/or catastrophic loss of export revenues or remittances and/or increasing costs of essential goods such as food and medicines. A GFSP would function as a stabilization mechanism (what

The third issue is that, for such countries, existing modes of development financing are inadequate to the task of stimulating universal social protection systems and floors. Not only is social protection a poorly funded area of development assistance, attracting less than 2 per cent of total bilateral official development assistance in 2018

The potential of a GFSP lies in its being able to directly address and overcome these obstacles. Its proponents see the added value of a GFSP as increasing and maintaining the necessary fiscal and policy space to support and sustain the long-term development of social protection systems, including floors. A GFSP, then, would be a major contribution to the vital task of filling the gap in the international financial and development architectures by kickstarting national investments in comprehensive social protection systems and floors. It would improve the predictability of external resource flows and provide large-scale international financing that guarantees governments access to the resources needed to realize a permanent social protection floor founded on the human right to an adequate income and health – even during periods of massive instability when it would be particularly important. A corollary of this is that institutional capacities would need to be developed at the country level to ensure the additional resources are adequately utilized and the benefits delivered to those who have entitlements. Governance across the implementation chain must not be taken for granted.

Crucially, the aim is not to replace domestic financing but to complement it through, among other things, catalytic interventions to crowd-in additional resources. International financing commitments would be transitional and temporary, with a finite lifespan over the medium term, after which the recipient country would graduate away from reliance on it. Thus, financing would not be open-ended. Indeed, the expectation is that international financing from the GFSP would taper off over time, as recipient governments increase their economic capacity to generate more resources to fund social protection. The ability of a fund to crowd-in domestic and other resources is therefore crucial to the idea of a GFSP. Advocates of a GFSP are keen to emphasize the centrality of country ownership (and, with it, responsibility and accountability), echoing the insistence upon it by the ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202)

Institutional bases for a GFSP

Against the backdrop of the long history of global development cooperation on social protection, the idea of a GFSP has emerged relatively recently as a prospective new dedicated multilateral financing mechanism to support the extension and strengthening of social protection systems and floors by mobilizing additional, dedicated finance. In this sense, it is filling an enlarging policy space far more open to the possibilities for reforming the global development financing architecture, in the spirit of global shared responsibility. At the same time, it entered a politically charged environment in which a range of policy actors, at national and international levels promulgate competing visions as to the aims and purpose of social protection and the forms that social protection systems including floors should take – whether universal or residual; whether they should provide a set of basic guarantees for all the population to protect them from a range of social risks over the life cycle or for the poorest people only; whether they should aim to prevent a catastrophic fall in living standards relative to the population at large or merely provide a minimum level of subsistence. The idea of a putative GFSP cannot escape these politically charged debates, including those pertaining to how international development agencies work together in partnership with each other and with country-level stakeholders.

The idea of a prospective GFSP is rooted in a strong institutional mandate that dates all the way back to the start of the UN system. The ILO Declaration of Philadelphia, 1944

Table 1.1. GFSP: a summary chronology of a developing idea, institutional reference points and policy advocacy in multilateral spheres of governance

|

1944 |

Declaration of Philadelphia, part of the ILO Constitution (Annex), states: “III. The Conference recognizes the solemn obligation of the International Labour Organization to further among the nations of the world programmes which will achieve” …. (f) “the extension of social security measures to provide a basic income to all in need of such protection and comprehensive medical care”. |

|

ILO Income Security Recommendation, 1944 (No. 67) and ILO Medical Care Recommendation, 1944 (No. 69). |

|

|

1948 |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights includes social security as a basic human right of all individuals (UN 1948) (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 22 and Art. 25, UN General Assembly resolution 217 A (III), UN document A/810, p. 71 (1948)).7 |

|

1952 |

ILO Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) (ILO 1952) establishes internationally agreed minimum standards for all nine branches of social security.8 |

|

2002 |

ILO Global Social Trust (GST) concept of an international social protection financing facility is proposed |

|

2003 |

The UN General Assembly establishes the World Solidarity Fund (proposed by Tunisia) to eradicate poverty and promote social development. Set up as a trust fund of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) |

|

2004 |

The ILO World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization concludes that “a certain minimum level of social protection needs to be accepted and undisputed as part of the socio-economic floor of the global economy” |

|

2009 |

The Ghana-Luxembourg Social Trust pilot is set up to finance maternity and child benefits for low-income families in one district, with the financial contribution of the Luxembourg trade union OGBL and technical advisory support from the ILO. |

|

The UN Chief Executives’ Board establishes the Social Protection Floor Initiative (SPF-I) calling for increased cooperation in development assistance activities and planning. |

|

|

2011 |

The Bachelet report |

|

2012

|

The International Labour Conference, at its 101st session, adopts the ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202) (ILO 2012). It envisages that ILO Members without sufficient national resources “may seek international cooperation and support that complement their own efforts” to finance national social protection floors (ILO 2012, para. 12). |

|

GFSP idea elaborated by Olivier De Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, and Magdalena Sepúlveda, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights |

|

|

Creation of the Global Coalition for Social Protection Floors (GCSPF), advocating for the Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202) and beyond (including the GFSP). |

|

|

Creation of the Social Protection Inter-Agency Cooperation Board (SPIAC-B), composed of representatives of international organizations and bilateral institutions, to enhance global coordination and advocacy on social protection issues and coordinate international cooperation in demand-driven country actions. |

|

|

2015 |

Sustainable Development Goals elaborated. SDG 1, target 1.3: implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable |

|

Addis Ababa Action Agenda on financing for development committed to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere” and commit to “a new social compact” providing “fiscally sustainable and nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors” |

|

|

2019 |

First estimates of the financing gaps for social protection by the ILO to provide evidence on the size of the problem and to serve as a basis for measuring progress (reduction of financing gaps). The study was updated in 2020 and a new update will be published in early 2024. In Our Common Agenda (UN 2021a), the UN Secretary-General uses the ILO estimates. |

|

2020 |

High-level expert meeting on the establishment of a global fund – social protection for all (22–23 September), convened by the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights and the Government of France. |

|

|

Alliance for Poverty Eradication, a group of 39 UN Member States meeting annually and seeking to kick-start the global economy through multilateral and multipronged efforts after COVID-19, was launched at the High-level Meeting on Poverty Eradication (30 June 2020) and inaugurated at the September meeting of the UN General Assembly. The UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights informed meeting participants of a process under way to establish a global fund for social protection. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) promotes the idea of a GFSP |

|

2021 |

GFSP discussed at various forums: Civil Society Policy Forum, World Bank; the Practitioners’ Network for European Development Cooperation; the 59th session of the UN Commission for Social Development; UN Human Rights Council |

|

|

The International Labour Conference conclusions provide a strong mandate for a GFSP. The Africa group supports the proposal for a GFSP |

|

UN Secretary-General in Our Common Agenda |

|

|

|

ILO “Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions” launched by the UN Secretary-General in 2021 (September) |

|

2022 |

Finance in Common Summit, Health and Social Protection High-Level Event, Abidjan. “Social protection agenda” emphasizes that social protection is a key global public good and an essential element of the global commons. It calls for “more agile pooled mechanisms at global level, to subsidize and incentivize investments at country level” It suggests inviting public development banks to join the UN Secretary-General’s Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions, “by aligning their financial assistance with the creation of decent employment in the health and care sectors, and the development of robust national social and health protection systems – thereby generating a virtuous cycle of public revenue creation and re-investments in people and the economy” |

|

2022/ 2023 |

Implementation of the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions, through global advocacy, resource mobilization and country-level engagement (see |

As table 1.1 suggests, the sources of influence on the idea of a GFSP are various. In addition to constitutional and legal bases that support social security as a fundamental human right, flagship reports on social protection reaffirm this right as indispensable to establishing a floor of socio-economic security that is integral to a fair globalization (for example, see

Accompanying these was the ongoing work by ILO to codify minimum standards and guidance for policy development in social security (protection) – the Income Security Recommendation, 1944 (No. 67)

Alongside these are international initiatives that have introduced mechanisms for financing universal social protection. In the early 2000s, the ILO GST initiative

At about the same time as the GST concept was elaborated by

Since then, outside the UN system and its normative framework, there has been the World Bank involvement in promoting global funds and innovative international finance. Of note recently is the Pandemic Fund, a financial intermediary fund which aims to provide a new stream of long-term funding to strengthen “pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response capabilities and address critical gaps” in low- and middle-income countries

Finally, the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions (hereafter, Global Accelerator), an initiative of the UN Secretary-General in which the ILO is playing a leading role, aims to spur domestic and international financial investment to support countries in realizing universal social protection floors. Launched in 2021, it aims to raise dependable resource streams from “a combination of national and international finances”

It would be remiss of us to give the impression that this advocacy terrain is static and homogenous. Indeed, just as there is no single proposal for a GFSP on the table, so there is no single campaign movement for a GFSP. Throughout this time, the leadership provided by the ILO, workers’ organizations and civil society as advocates of universal social protection worldwide has been notable. Not only is the ILO the lead UN agency for international labour standard-setting and an advocate of universal social protection systems (including social protection floors guaranteeing access to essential healthcare and basic income security), but it has also worked with social partners and civil society groups to draw attention to the potential significance of a global financing facility dedicated to building social protection in the poorest countries of the world. Campaigning for a GFSP has been undertaken by the GCSPF and the ITUC. The GCSPF, which brings together more than 200 civil society organizations, trade unions and non-governmental international development actors, has been instrumental in galvanizing support for a GFSP and undertaking studies that develop and refine possible ways in which a prospective GFSP could be set up (see, for example, the studies commissioned by the German-trade-union-funded Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung –

The fact that such a global mechanism for social protection has gained great prominence and propulsion is an historic moment in the global political economy of poverty and inequality. In part, it reflects the dismal track record of poor leadership by the international community to remedy international financial and development architectures in ways that would channel investment in social protection systems and floors and address international perma-crises that derail global social development efforts. The global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic clearly showed that all countries are interdependent and that countries enjoying robust social protection systems could better face these crises. It also reflects the growing significance of global funds in the development financing architecture. Global funds have become key fixtures in the global financial and institutional architectures of development, commanding ever-greater resources dedicated to ensuring that countries can better face potentially socially, economically and ecologically catastrophic events.

Research questions and analytical framework

It is not yet clear whether there should be a GFSP at all, let alone what form the governance structure of a prospective long-term financing vehicle could take in practice. An integral part of ongoing discussions about a potential GFSP necessarily encompasses a range of issues to do with its governance. Indeed, as with any ambitious proposal, there are complex challenges and questions to be addressed as regards optimal governance arrangements for a prospective GFSP, even besides the overarching question of determining the most appropriate financing mechanism for the given purpose(s). Answers to such questions are invariably informed by experience, by principles and by politics. The latter is naturally outside the scope of this report, although we acknowledge the highly political context of discussion and debate about a potential long-term financing mechanism earmarked for social protection. Developing the general principles underpinning a GFSP mechanism is not the focus of this paper, though we note here the work of

The approach we take in this study focuses on the experiences of extant global funds as regards the institutional characteristics of their governance arrangements. Such characteristics structure the conditions under which decision-making takes place as regards, first, how resources are generated and mobilized, allocated and spent; second, the relationship between the global fund and the recipients of finance; and third, the features of projects or programmes that are financed. The remainder of this chapter elaborates the research questions structuring this study and sets out the conceptual framework that gives shape to our data gathering and analysis and presentation of findings.

Our study is steered by two questions:

Research question 1: What are the experiences of setting up and running global funds?

Research question 2: What are the lessons from these experiences for the design of a putative GFSP?

These questions respond to a range of issues regarding the governance structure of a GFSP that are to be resolved. These pertain to the institutional design of a prospective GFSP, its size and shape, whether it would be a stand-alone funding mechanism or embedded in an existing institutional home, what its funding sources and mechanisms would be, and the standards and indicators against which its performance would be measured.

At the macro institutional level, questions arise as to where a possible GFSP would “sit” within existing global institutional governance structures. For example, would it be an autonomous entity, sitting outside existing international organizations, or would it be tethered to, or even embedded in, an existing organization? What would a GFSP mean for the work of other international organizations and institutions? These include financial stability, investment and development institutions (International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, regional development banks), UN organizations whose remit incorporates, directly or indirectly, social protection (the ILO, the WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the UN Children’s Fund, the UNDP) and subglobal world/regional organizations (within and outside the UN system). Might the creation of an additional fund lead to a problem whereby the proliferation of sector- or issue-specific (vertical) funds leads to duplication of effort and over-complexity? Or might it actually strengthen, consolidate and scale up existing efforts in the realm of social-protection-specific development financing?

Bilateral and multilateral donor structures are often criticized for paying lip service to the necessity of country ownership, but how could this be ensured by a global fund? What sorts of institutional structures, arrangements and practices at fund level and country level might be necessary to secure the ongoing commitment of governments over time? Government commitment over the long-term would be essential, but often falls foul of the electoral politics of policy, whereby a programme associated with a previous government is deprived of funding after a new government is elected. In this context, how could a GFSP help forge cross-class and cross-party alliances to provide stability over the long term? And where would non-governmental actors sit in relation to this? Would they have a role in the governance of a GFSP, or would they be confined to being a local implementer (i.e. service delivery)?

A range of questions arises as to how to secure a sufficiently voluminous and reliable stream of funding and how to ensure it reaches the areas and populations in most need of a coherent and functioning social protection system. Where on the spectrum of “fully funded by public donors” to “fully funded by private-sector sources” would a GFSP sit? Would finance only be open to governments or to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as well? If it is open to NGOs, then would that be maximally inclusive – not just of charities and social partners, but businesses and private-sector foundations, as well as citizens (e.g. through crowdfunding)? Might a GFSP divert extant funding away from official development assistance for social protection or from another sector (e.g. health), or could it generate a net increase in the amount of finance available?

Looking at the experiences of extant global funds through the lens of questions such as these can help to bring to the surface the sorts of challenges involved in setting up a GFSP and strengthen the evidence base feeding into decision-making on a range of crucial issues.

We use a conceptual framework that identifies five major elements of fund governance, as set out below.

(i) Organizational and institutional structures of the fund: These condition the donor-recipient relationship, including the power dynamics between them, their respective roles in the design of funding mechanisms and decision-making and, ultimately, their accountability.

(ii) In-country stakeholder engagement, country ownership and coordination with national authorities and donors: Engagement with and ownership of a fund is vital to the strong commitment by all stakeholders over the long term. Stakeholder involvement, including the social partners, is vital to the design and implementation of an effective funding mechanism capable of realizing its goals, as well as to enacting democratic control over the fund and for accountability. Country ownership and in-country coordination are similarly vital to the effectiveness of the fund and how well the finance from the GFSP is used to meet nationally defined priorities and goals.

(iii) Resource mobilization and the development of affordable and sustainable financing: Being able to generate or mobilize reliable revenue streams of national and international sources of finance is critical to a fund’s success. Where such finance comes from, how it is managed, and how it is allocated are not just vital operational matters, but core ones of governance. Moreover, they fundamentally define the characteristics of what is funded and the credentials and legitimacy of the fund itself. Sustainability is not just about affordability, but also about whether resources (from global and national sources) continue to be “crowded-in” over time, whether the investments generate a virtuous cycle of investment leading to better outcomes for social protection systems, including floors, increased fiscal space for social protection and integration of social protection finance into national budgeting frameworks, as well as the terms on which a country “graduates” away from the fund.

(iv) Quality of investment and alignment with human rights and international labour standards: The quality of social protection investment should be judged by reference to clear standards and benchmarks that are transparent and known to all from the outset. This is not just about whether the resources invested meet their defined goals, but about the terms on which they do that. This includes whether they attain agreed international social and environmental standards and adhere to international human rights norms and law. These are a core governance issue, and careful institutional design plays a major role in assuring and enhancing the quality of investments made.

(v) Strong focus on data, results, learning and innovation: Being able to adapt in the light of circumstances, including unforeseen ones such as covariate shocks, is crucial to the flexibility that a fund needs to operate well and that stakeholders need to cooperate effectively in the interests of national universal social protection floors. Knowing how well (or poorly) a fund performs is therefore vital for knowing, learning and innovating, as well as for sustainability and accountability. The arrangements a fund makes for collecting, analysing and sharing data on all aspects of the fund’s operations, including the impact of the fund on the reduction of financing gaps for social protection, is a crucial governance matter.

Research design and methods

This chapter presents the rationale driving our selection of global funds, describes sources of information and data comprising the underpinning research for this paper, and reports summary results of our data search.

Selection of global funds

The terms of reference for this study specified health, health-related, agricultural and climate global funds for investigation. Regarding the global health funds, we scrutinized the GFATM and Gavi plus the health-related GFF. In the case of the agricultural funds, we initially included IFAD and the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program, but subsequently excluded the latter owing to a lack of available data. We selected three principal multilateral climate funds for investigation: GEF and its associated subfunds, the LDCF and the Special Climate Change Fund; the GCF; and the AF (see table 2.1).13

Table 2.1. Global funds selected14

|

Fund |

Abbreviation |

Sector |

|---|---|---|

|

Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria |

GFATM |

Health |

|

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance |

Gavi |

Health |

|

Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents |

GFF |

Health |

|

International Fund for Agricultural Development |

IFAD |

Agriculture |

|

Global Environment Facility Least Developed Countries Fund Special Climate Change Fund |

GEF LDCF SCCF |

Climate |

|

Green Climate Fund |

GCF |

Climate |

|

Adaptation Fund |

AF |

Climate |

This selection of global climate funds gives a good mix of older and more recently established funds, larger and smaller funds, and funds which have a mix of purposes (two focus on mitigation and adaptation; two focus on adaptation only). The GCF is the largest of the four, and has experienced challenges associated with its creation and smooth running. The LDCF, being directed exclusively at the poorest countries, raises interesting issues given the focus of a proposed GFSP. The AF, a moderately-sized fund by comparison with GEF and the GCF in terms of finance, is notably the only climate fund to give developing countries direct access to adaptation project resources.

Research methods

The underpinning research for this paper has been generated from structured literature reviews, documentary analysis of “grey” literatures, and interviews.

We undertook a rapid structured literature review of academic and grey literatures on global health, agriculture and climate funds to build the most comprehensive research and publications base consistent with project resources. We used EBSCOhost and Google Scholar data-bases for academic literatures, using search inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our search terms included the formal names of the funds, as well as alternative terms and synonyms. We made a selection from the returns to exclude low-quality and non-relevant publications (Annex 2), and further sifted returned items for relevance and quality. We took special care to search actively for the widest range of evidence and perspectives. The bibliographical references comprise 80+ academic publications and 130+ grey publications, of which by far the overwhelming part are global funds’ own documents.

In addition, we undertook English-language semi-structured qualitative interviews with 22 current or former senior officials of global funds and academic and non-academic experts in global funds in one of the sectoral areas of the study. Interviews were carried out between June 2022 and February 2023, with three purposes in mind. One was to gather core data to build our global funds database. A second purpose was to gain officials’ and experts’ knowledge and insights as to the governance of global funds. A third purpose of the interviews was to consult on key governance aspects of a prospective GFSP. These latter interviews were held with social protection experts. All interviews took place online with the respondents at their place of work and were recorded.15 The interviews were professionally transcribed using the intelligent verbatim mode of transcription.16

The overall response rate (ratio of requests for interview to interviews secured) was relatively low (about 3:1), especially in the agricultural sector. Table 2.2 presents the number of interviews undertaken according to sector and type of organization.17 Of the 22 experts we interviewed, 11 were women and about half were based in a “global South” country (defined as a lower middle-income or low-income country), which may be taken as a proxy (but highly imperfect) indicator of a “Southern perspective”. Interviewees were from diverse ethnic backgrounds and nationalities, though White Western individuals predominated. Annex 1 provides further summary information about the interviewees, including the identities of those interviewees who gave their express permission to be named in the report.

Table 2.2. Interviews done by sector and type of organization

|

Global fund |

University, research institute, foundation |

Employer |

Trade union |

International organization |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agriculture |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Climate |

3 |

||||

|

Health |

7 |

1 |

|||

|

Social protection |

5 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Ethics and data protection

Protocols governing research conduct, information management and data protection, among others, were approved by the Open University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: HREC/4406/Yeates). The research data, in particular the consent sheets, audio files and transcription files, and all working documents, are kept in a secure project fileshare hosted by the Open University. The interviews were transcribed and anonymized by a professional transcription company and further checked by the research team.

Contextual overview and comparison of global funds in health, climate and agriculture

Introduction

The global funds within the scope of this study differ markedly in their histories, revenue sources and the amount of finance they command, access and allocation criteria, activities supported, institutional structure, stakeholder participation, safeguarding and equality policies and learning mechanisms. This chapter provides a descriptive summary profile of the global funds and draws out key points of contrast and comparison between them.

As an introduction, it is important to note that “global fund” is a generic term that masks an important distinction between a fund and a financing facility. The former is broadly understood as a sum of money providing development assistance to deliver goods and services, and the latter as a mechanism to leverage resources from governments, development banks, the private sector and other sources for fund-specific interventions.18 The GFATM, Gavi, the LDCF, the AF, the GCF and IFAD are examples of a fund, while the GFF and GEF are examples of a financing facility (as their full titles suggest – see table 2.1). In this respect, financing facilities are not independent funds with legal personality and do not provide development assistance as such. Rather, they mobilize public and private finance for interventions and deploy smaller amounts of grant resources to scale up that finance. The GFF, unlike the disease focus of the GFATM, invests across diverse areas to promote reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and nutrition (RMNCAH-N) aims (e.g. health systems strengthening, sexual and reproductive health and rights, cash transfer programmes). The GFF is, to all intents and purposes, a World Bank mechanism (it is hosted by the World Bank in Washington, DC and its secretariat is staffed by World Bank officers). In GEF’s case, it was established as a financial mechanism for five major international environmental climate conventions, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); it is an international partnership for which the World Bank is trustee. Its role is to help to mobilize resources through a replenishment process every four years.

Annex 3 provides a summary profile of each of the global funds in the study and is a key reference point for the discussion in this subsection. In what now follows, we briefly elaborate on the features of the global funds and their similarities and differences. This provides the informational basis as to the institutional features of global funds’ governance structures. In Chapter 4, we present key findings of our study, using the conceptual framework outlined in Chapter 1.

Origins and initiating logic

The oldest of the global funds is IFAD, operational since 1978 (Annex 3, column 2). Many of the other global funds in our study were established in the early 2000s (Gavi, the AF, the LDCF, the GFATM); the most-recently established (the GCF and the GFF) were set up in 2010 and their first projects funded in 2015. Most of the new generation of vertical funds emerged during the era of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000–15). Thus, Gavi and the GFATM map on to health MDGs to reduce child mortality (MDG 4), improve maternal health (MDG 5), and combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other communicable diseases (MDG 6). The AF and the LDCF map onto MDG 7, aiming “to ensure environmental sustainability”. More recently, the SDGs prompted the establishment of the GFF. Launched in 2015 by the UN as the Global Financing Facility for Every Woman, Every Child, the GFF seeks to accelerate progress towards the SDGs for RMNCAH-N.

The political economy justifications for establishing the funds and conditions under which finance is disbursed are worthy of comment. In respect of global health funds, treatments for tuberculosis, malaria and HIV and vaccines typically require expensive medical products. Not only was a lack of financial means a clear barrier to accessing those products, there was also a clear rationale for pooling resources among purchasing countries to bargain collectively for a better price for the products under conditions of monopoly/oligopoly pricing. Most of the global climate funds, by contrast, serve or are closely related to UNFCCC activities. The UNFCCC’s long-standing principle of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities” has led to developed countries providing support (financial or otherwise) for developing countries. This is in part in recognition of: the disproportionate impact that developed countries have had on climate change; the opportunity, with the appropriate level of support, for development to take place in a low-carbon manner; and the realization that support is required to protect developing countries from the harmful effects of climate change through mitigation and adaptation. The genesis of the AF as a “compensation” fund not a “donor” fund

As to the overall aims and focus of the funds, the health funds presently self-describe as promoting health systems strengthening; the agricultural funds as eradicating poverty and hunger and the climate funds as strengthening resilience in the face of climate change (see Annex 3, column 4). IFAD is the only fund in our study to deliberately target (rural, farming) people living in poverty. The way the funds work in practice varies greatly, but all use targeting mechanisms operationalized variously through the prism of the degree of vulnerability of a country (the LDCF, the GCF) or community (the AF) to climate change impacts or the degree of disease burden and lowest economic capacity (the GFATM, Gavi), or through “targeted strengthening” of healthcare systems for designated gender and age groups (the GFF), diseases (GFATM) or immunization (Annex 3, column 4). The term “health systems strengthening” means building permanent institutions that provide health services over the long term (see footnote 3 above), so the use of this term by vertical global health funds is notable because they do this in a narrow way, for a small number of communicable diseases (the GFATM), immunization (Gavi) or designated populations (the GFF). This highlights a tension between the overt aim of system strengthening as the rationale, versus the concrete operational work, which is narrow and highly targeted. On this point, GFATM’s strategic focus on building health systems through a disease-specific lens is potentially an impediment to investment in the social protection needed to realize comprehensive coverage of multiple populations, risks and needs across the life course.

Just as the originating context, initiating logic and aims of the global funds vary, so do their institutional “personality” and “home” (see Annex 3, column 3). IFAD, the GFATM, Gavi, GEF, the AF and the GCF are stand-alone entities with secretariats independent of any other organization. The GFF, as noted earlier, is housed in and run by the World Bank. The LDCF is housed in and run by GEF. The World Bank runs and/or is trustee and disburser of funds for five of the eight funds – all the climate funds in this study, plus the GFF. All the global funds are located in and run by the global North, in the United States of America (Washington, DC) and Western Europe (Germany, Italy, Switzerland), except for the GCF, which is based in the Republic of Korea.

It is notable that the global climate funds function almost exclusively as financing vehicles for the UNFCCC

Fund size and resources

Fund size, as measured by the size of the portfolio of financial resources available, varies considerably (see Annex 3, column 5 and tables 3.1 and 3.2 below). Tables 3.1. and 3.2 give figures for official development assistance and country-programmable aid for six of the seven funds that we look at (the OECD does not have data for GFF). The largest global funds (by volume of funds) are GFATM, Gavi and IFAD (tables 3.1 and 3.2), which together make up the majority of the total volume of resources commanded by these global funds. It is notable that GEF was bigger than IFAD before 2017, but was overtaken by IFAD thereafter.

Table 3.1. Global funds, official development assistance, millions US$, 2011–21

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AF |

45 |

23 |

7 |

39 |

46 |

42 |

32 |

50 |

66 |

77 |

60 |

|

Gavi |

776 |

1035 |

1484 |

1355 |

1833 |

1433 |

1767 |

1557 |

2139 |

1993 |

1607 |

|

GEF |

631 |

650 |

723 |

806 |

864 |

911 |

487 |

458 |

289 |

402 |

451 |

|

GFATM |

2506 |

3254 |

3854 |

2765 |

3443 |

3852 |

4475 |

3309 |

3683 |

4255 |

4907 |

|

GCF |

|

|

|

|

0 |

3 |

67 |

136 |

264 |

440 |

622 |

|

IFAD |

|

|

|

|

580 |

641 |

720 |

649 |

751 |

663 |

624 |

|

Total |

3958 |

4962 |

6067 |

4965 |

6767 |

6884 |

7549 |

6159 |

7191 |

7829 |

8271 |

AF: Adaptation Fund; Gavi: Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance; GCF: Global Climate Fund; GFATM: Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; GEF: Global Environment Facility; IFAD: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Source:

Table 3.2. Global funds, country-programmable aid, millions US$, 2011–20

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AF |

34 |

17 |

7 |

29 |

32 |

34 |

31 |

41 |

60 |

66 |

|

Gavi |

644 |

923 |

1314 |

1240 |

1637 |

1340 |

1388 |

1382 |

1804 |

1577 |

|

GEF |

|

527 |

615 |

676 |

718 |

772 |

369 |

351 |

217 |

333 |

|

GFATM |

2506 |

3254 |

3854 |

2765 |

3441 |

3852 |

4475 |

3301 |

3668 |

4241 |

|

GCF |

|

|

|

|

0 |

3 |

54 |

96 |

254 |

424 |

|

IFAD |

|

580 |

560 |

486 |

558 |

622 |

709 |

639 |

744 |

655 |

|

Total |

3184 |

5301 |

6349 |

5196 |

6386 |

6623 |

7026 |

5810 |

6748 |

7296 |

Note: “Country-programmable aid is the portion of aid that providers can programme for individual countries or regions, and over which partner countries could have a significant say. Developed in 2007, country-programmable aid is a closer proxy of aid that goes to partner countries than the concept of official development assistance (ODA)”

AF: Adaptation Fund; Gavi: Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance; GCF: Global Climate Fund; GFATM: Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; GEF: Global Environment Facility; IFAD: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Source:

The GCF is the only fund in this study not to require co-financing as a condition of award. The co-financing requirement is a relatively new one, instituted as a result of criticism of the (non)sustainability of the activities funded. It is also important for the legitimacy of the funds; as one interviewee emphasized during discussion of the GFF, African governments’ contributions to GFF funds are important for this reason. Otherwise, the funds vary as to how they incorporate the required contributions in their revenue. The overall value of Gavi and GFF funds, for example, includes country contributions; Gavi also includes the value of countries’ self-funded vaccine programmes in the size of its funding “pot”. The global funds also differ in the way the co-financing requirement works in practice. Thus, among the global health funds, GFF requires (among other things) that recipients commit to mobilizing additional complementary finance and/or leveraging existing financing. The GFATM operates what it calls “catalytic investments”, meaning that countries putting domestic resources towards programmes for GFATM-prioritized populations are eligible to receive GFATM funding. Both the GFF and the GFATM permit debt cancellation in return for the recipient country releasing funding for fund-prioritized interventions. Among the climate funds, the LDCF requires baseline resources to be provided by the recipient country as a condition of receiving funding, while GEF assumes co-financing, or “blended finance”, as it will only cover the agreed incremental costs of measures to achieve global environmental benefits. The AF is the outlier in terms of climate finance. It receives some funds from overseas development assistance, some from private donations and some via the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol. These funds are not worth as much as they used to be, since the value of carbon credits has fallen, but nonetheless this has afforded the AF greater financial freedom compared with climate funds dependent on overseas development assistance.

In practice, the co-financing requirement is rather theoretical, because thus far most governments find it difficult to match the funding, since resources are very limited at national level. In these conditions, the co-financing requirement means there is an incentive for governments to redirect funding towards the priorities of the global fund, which, in the health arena, may focus on a single disease or single age group. Co-financing of climate adaptation projects by private-sector funding sources is problematic when compared with mitigation projects; it is far harder to lever in private investment because adaptation activities are not regarded as marketable (for example, it is less profitable to build a wall that stops a flood compared with investing in renewable energy).

Blended finance aims to combine finance sources such as development funds and private capital. Guarantees that protect investors from capital loss, subordinated or concessional loans, and equity (often junior equity that accepts higher risks for lower returns) are the most commonly-used instruments

Sources of income and their share of the overall contribution vary among the funds (see Annex 3, column 6). Governments are the largest contributors to the global health funds (particularly the GFATM, 92 per cent of whose funding is governmental (with the remainder coming from the private sector and foundations);21 donors contribute 60–80 per cent of Gavi’s revenue each replenishment cycle) and the global climate funds (governments are the only contributors to GEF). LDCF is reliant on voluntary contributions, which is a concern, being a source of instability

All of the global climate funds and the IFAD permit government contributions to count in their overseas development assistance; none of the global health funds (by their own account) do so. The GFF is funded almost entirely by the World Bank Group, though no data are available about where this funding originates. Private-sector (corporations, foundations) donors, NGOs and individuals are commonly listed among other (non-state) contributors. Other sources of income derive from loans (a significant revenue stream for IFAD), returns on investments (e.g. IFAD) and “innovative financing mechanisms”. On this latter point, the AF receives a 2 per cent share of proceeds from the Clean Development Mechanism, though the falling market value of certified emission reductions prompted the AF Board to diversify the number of contributors and fundraise actively

Over the past 15 years, the World Bank has encouraged and enabled Gavi to rely heavily on innovative mechanisms of financing,22 which account for 23 per cent of its total income (Global health expert 2 interview; Annex 3). The role played by Gavi in designing the IFFIm mechanism to raise money from capital markets was highlighted as a successful approach to crowding-in resources. However, the involvement of profit-seeking financing mechanisms in generating funding revenue also raises potential conflicts of interest, and the need to prevent actors that are seeking profitable returns on investments having a voice on the Gavi Board. This was a key reason for setting up the IFFIm as an independent entity outside Gavi (Gavi representative 1; Global health expert 2).

One issue of note is the reported interest by GFF in exploring avenues for innovative financing with governments. One of the successful examples mentioned was taxation of sugar or sweetened beverages or tobacco to contribute to resources earmarked for the health sector, which was seen to be typically welcomed by some ministries of finance. Tax levies are not universally welcomed, however, or are diverted to policy priorities other than those originally intended, as one interview participant explained:

There are other aspects relating to taxation of commodities which have been discussed, but rarely put in place, … as for example, to put a sustainable development fund in place based on resources coming from the exploitation of oil. There were discussions also on setting up development investment bonds in a couple of countries … [but] the critical mass in terms of investor was not enough for the instrument to fly. … [W]e had discussed at some point with the ministry of finance the mobilization of resources coming from the diaspora ... The problem here was to earmark these resources and the discussion took place in a context where the government had a lot of competing priorities (GFF representative 1).

While private-sector companies tend to be willing to invest in associating their image with a “good cause”, this may be much more difficult in cases of a complex intervention or investment mechanism. Development impact bonds, in particular, are found to be difficult to explain to recipient governments and investors because of their relatively complicated structure in terms of who subscribes and to what extent and what the “pay-off function” looks like (GFF representative 1). However, the GFF has deployed this approach in Cameroon, where it is seen to be a strong pathway to sustainable change (Global health expert 3).

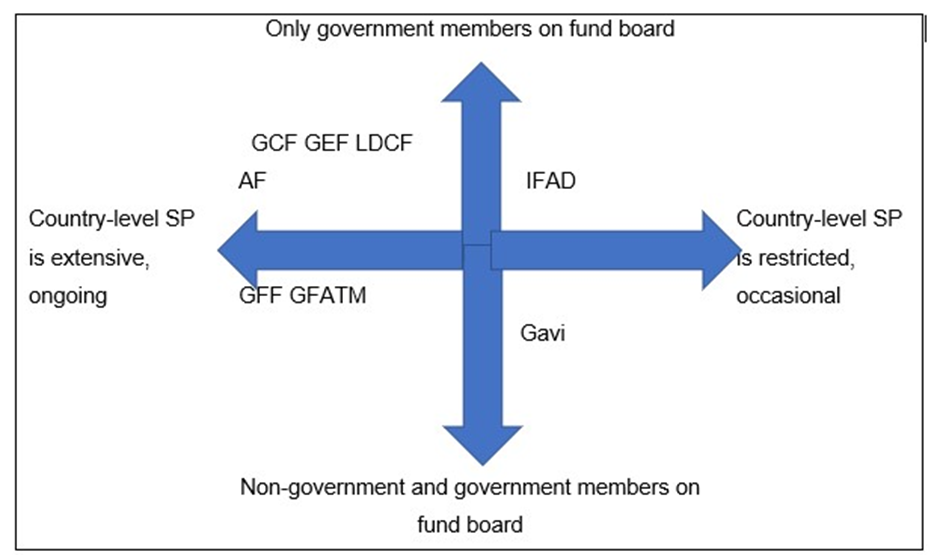

Mode of access to funding

The mode of access to funding is an important dimension of the institutional characteristics of global funds’ governance. The access modality structures funding decisions, the flow of finance and the relationship between the global fund and recipients of finance, including the characteristics of projects being financed

Most of the global funds in this study operate direct modes of access, except GEF and the LDCF (GEF manages the LDCF). GEF has 18 designated partner agencies, principally made up of regional development banks, UN environmental agencies and conservation-oriented civil society organizations.23 Applicants to the LDCF must apply through a GEF agency, although proposals are reviewed against criteria that include “country ownership”, where projects should be priority activities as per the country’s national adaptation programme of action

The direct-access model aims to give countries enhanced ownership and to support domestic, notably local, capacity-building. The AF, in particular, supports “concrete adaptation projects” and is designed to be implemented at the subnational/local level

The direct access offered by the AF was regarded as novel at the time and was something that developing countries fought for during its creation

The direct-access model has been praised by civil society

Global funds using the direct-access mode operate different models. IFAD applicants, which can include governments, apply directly to IFAD. Global climate funds applicants can do similarly or through accredited implementing agencies. For the AF, once a country has the necessary structures and accreditation in place, funding applications can be made directly to the AF by a national implementing entity (NIE), or regional implementing entity (RIE) and funds are also directly managed from design and implementation through to evaluation by the NIE/RIE. Where a country is unable to meet the criteria for direct access, funds can instead be accessed through multilateral implementing entities (MIEs) such as UNDP, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNEP, the World Bank and regional development banks. In the case of the GCF, partner agencies are similar to those in the AF but also include commercial banks, equity funds and civil society organizations. In the case of the GCF, nationally designated authorities nominated by the relevant government play a key role. To gain direct access, nationally designated authorities based in the country nominate subnational, national, or regional institutions for accredited entity status. Once granted, as with the AF, accredited entities/direct-access entities can apply for funds without international accredited entities (IAEs). Implementing entities (MIEs, NIEs) are the major channel through which GCF funds are disbursed to recipient countries

Direct access in Gavi’s case is strongly government-led, based on submissions by the ministry of health and endorsed by the ministry of finance and a national coordinating body. In the case of GFATM, country-level multi-stakeholder partnerships (country coordinating mechanisms) identify national needs and a public-sector or private-sector organization within the country to be the principal recipient of the funds, which then disburses them (cf.

The AF is regarded as a highly innovative and successful form of climate finance as it uses a direct-access model. It departs from the GEF model, based on indirect access and official development assistance, meaning that funds are usually applied for and managed by an intermediary – usually a multilateral agency – and are subject to its governance structure

However, the risks of direct access are also highlighted in the literature, with donors expressing concerns about transparency, accountability and risk management at the recipient level

The significance of enabling conditions is reflected in research findings concluding that the designation of direct access mode does not automatically guarantee the aimed-for benefits. Reviews of the AF and GCF, for example, have both indicated dominance of IAEs in their early stages. Brown, Bird and Schalatek (2010, p. 4) found a dominance of MIEs in the AF; in the first round, 21 of 22 proposals involved MIEs, with 18 from the UNDP “which stands to gain $8.5 million in project cycle management fees”. This dominance led to an early criticism that “business as usual” was continuing, counter to the principles of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (Brown, Bird, and Schalatek 2010). Given this concern, in 2010 a cap of 50 per cent of the budget was placed on the number of MIE-led projects to ensure balance and improve direct access

Similarly, early research into the GCF found that most funding was being handled by three large IAEs – the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank and the UNDP

Eligibility and transition policies

The criteria used to award project applications and arrangements for transitioning out of global fund finance are also vital to defining the global fund–recipient relationship. The oldest global fund, IFAD, operates an incredibly wide range of criteria,27 as perhaps would be expected for a fund dedicated to a goal as broad as rural economic development; the AF has a similarly broad mission to support vulnerable communities in developing countries in adapting to climate change. All the global funds work by financing specific time-limited projects, often on a performance- or results-based basis. In the LDCF’s case, it supports governments in developing national programmes aligned to the fund’s mission. The principle of country ownership means that fundable projects are usually required to be based on country needs, views and priorities. This is made explicit by two global climate funds, the AF and GEF. Thus, GEF states that projects must be driven by the country (as opposed to an external partner), in particular government projects and programmes, and be consistent with national priorities that support sustainable development. Also, applicants to GEF are required to have co-financing.