World Social Protection Report 2024–2026

Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition

Chapter 3. Getting the basics right: Closing protection gaps and strengthening systems

Key messages

-

For social protection systems to fulfil their potential in responding to climate change and addressing life-cycle risks, they must be reinforced and adapted. Additional efforts are needed to ensure universal coverage and comprehensive and adequate protection. Adaptive social protection requires actions to enhance the resilience and responsiveness of social protection systems during crises, including those caused by climate change.

-

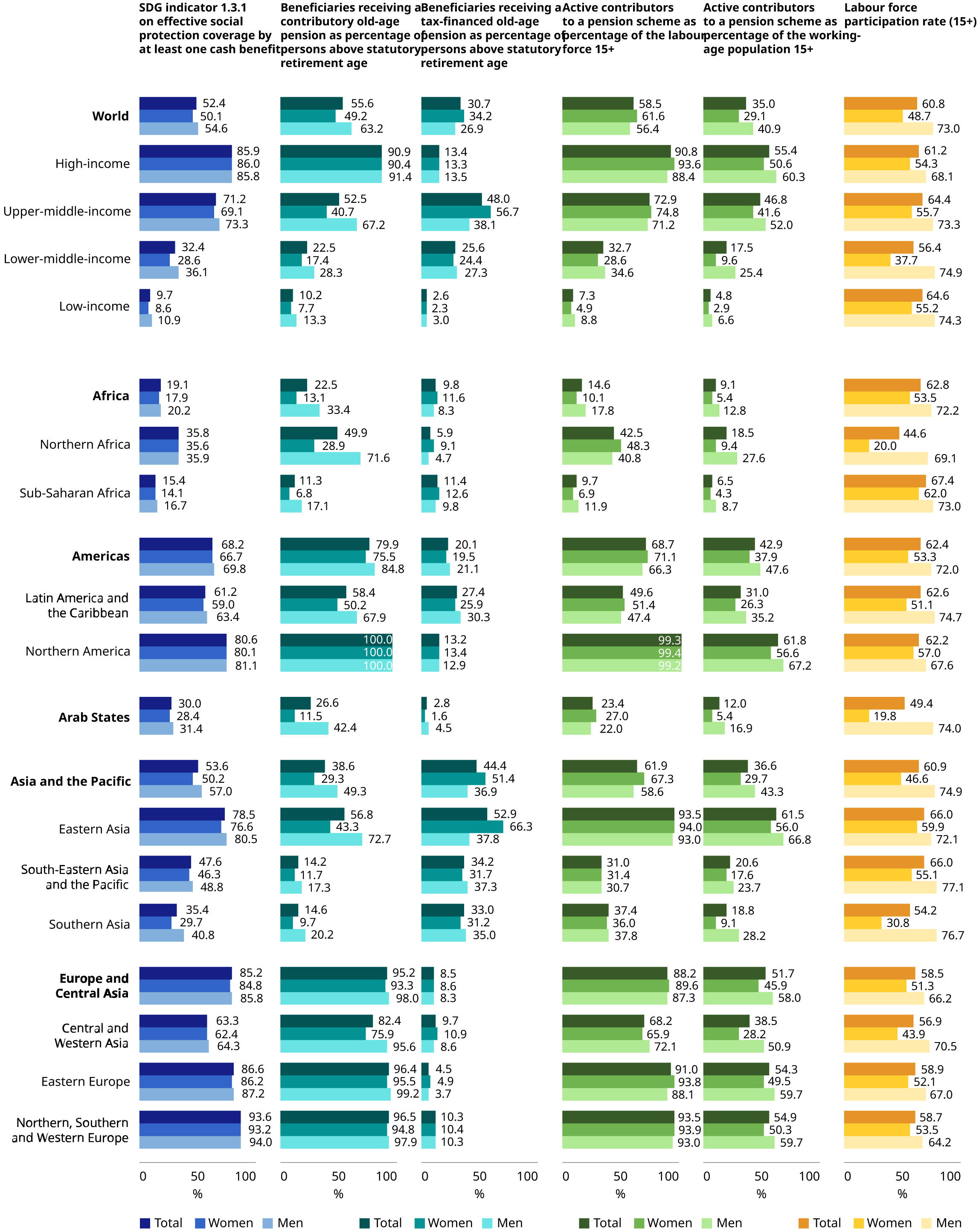

For the first time, more than half of the world’s population (52.4 per cent) are covered by at least one cash social protection benefit (SDG indicator 1.3.1), representing an increase from 42.8 per cent in 2015. While this constitutes important progress, an alarming 3.8 billion people remain entirely unprotected. If progress were to continue at this rate at the global level, it would take another 49 years – until 2073 – for everyone to be covered by at least one social protection benefit.

-

The world is currently on two very different and divergent social protection trajectories: high-income countries are edging closer to enjoying universal coverage (85.9 per cent), and upper-middle-income countries (71.2 per cent) and lower-middle-income countries (32.4 per cent) are making large strides in closing protection gaps. At the same time, the coverage rates of low-income countries (9.7 per cent) have barely moved since 2015.

-

Countries at the front line of the climate crisis and most susceptible to its hazards are woefully unprepared. In the 50 countries that are most vulnerable to climate change, only 25 per cent of the population are effectively covered, leaving 2.1 billion people facing the intensifying impacts on livelihoods, incomes and health without any social protection. In the 20 most vulnerable countries, less than 10 per cent of the population is covered, leaving 364 million people wholly unprotected.

-

Gender gaps in global legal and effective coverage remain substantial. Social protection systems must become more gender-responsive and address inequalities in labour markets, employment and society at large.

-

Increasing the adequacy of social protection is paramount to realize its potential to prevent and reduce poverty, address inequalities and enable a dignified life. Ensuring adequate benefits across the life cycle is key to guaranteeing universal social protection and striving towards higher benefit levels. The climate crisis will increase human needs, and require a commensurable increase of the range and level of benefits to address new and transformed risks.

-

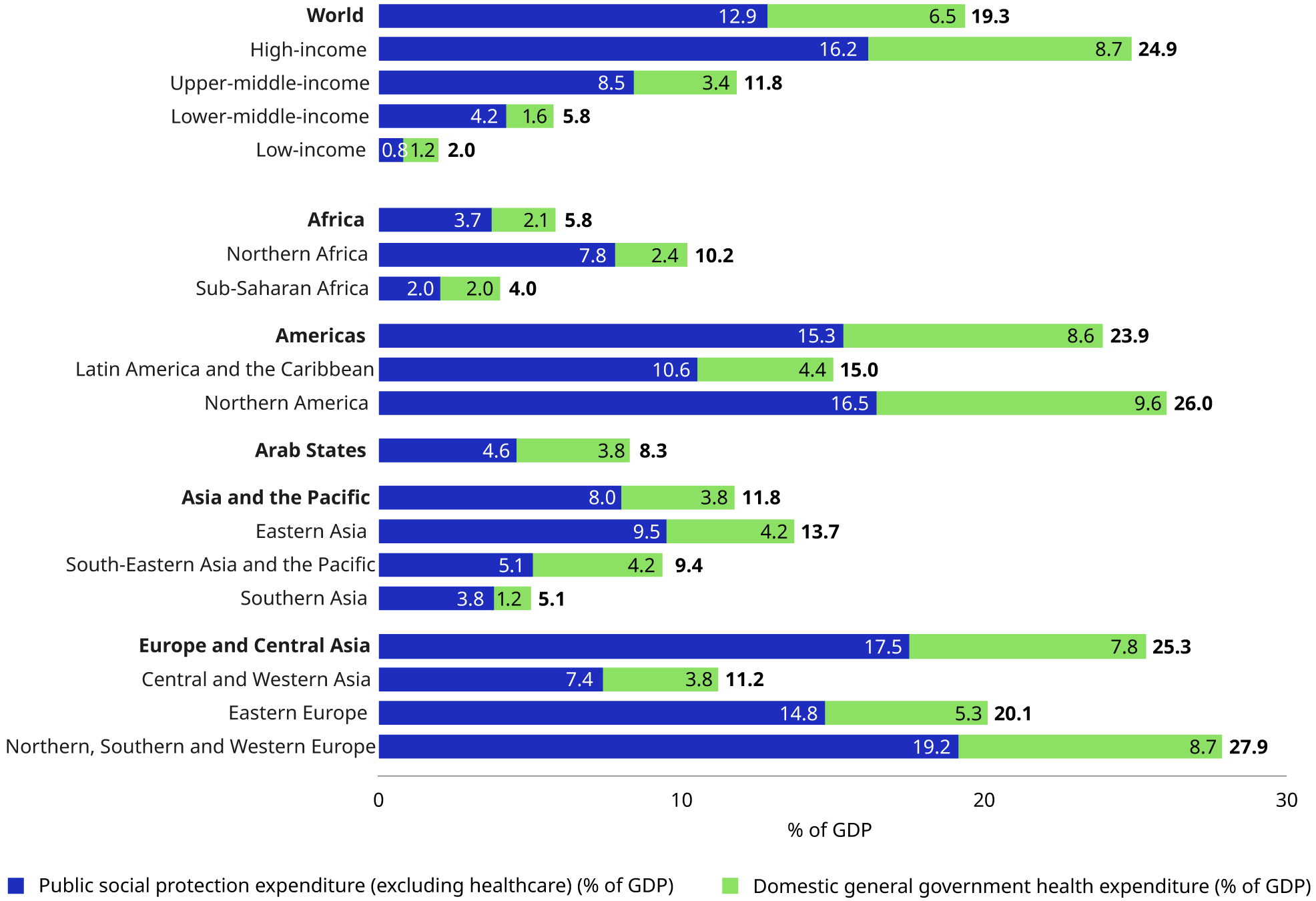

Countries spend on average 19.3 per cent of their GDP on social protection (including health), but this figure masks staggering variations. High-income countries spend on average 24.9 per cent, upper-middle-income countries 11.8 per cent, lower-middle-income countries only 5.8 per cent, and low-income countries a mere 2.0 per cent of their GDP.

-

Financing gaps in social protection are still large. To guarantee at least a basic level of social security through a social protection floor, lower-middle-income countries would need to invest an additional 6.9 per cent of their GDP and upper-middle-income countries 1.4 per cent. Low-income countries would need to invest an additional US$308.5 billion per year, equivalent to 52.3 per cent of their GDP, due to their large social protection coverage gaps and low GDP, which will not be feasible in the short term without international support.

-

Options exist to fill financing gaps while tackling climate inequalities within and between countries. This includes taxing those who consume and produce more carbon emissions (including by removing subsidies) and redistributing revenues through social protection. International climate finance, including for loss and damage, should be used to strengthen the resilience of the most vulnerable countries, including through social protection.

-

Social protection systems must be adapted to face the challenges posed by the climate crisis. Adaptive social protection requires increased coherence and coordination between social protection and climate policies, costing and financing strategies that consider climate risks, flexible scheme design and investments to enhance the resilience and responsiveness of operations and benefit delivery.

.3.1 Where do we stand in building social protection systems?

In the face of the climate crisis, establishing permanent comprehensive provision in the form of universal and adaptive social protection systems is indispensable to prepare for the escalating impacts it will inflict. The alternative – scrambling to assemble last-minute, residual and suboptimal responses that do not reach everyone – is simply not a rational and responsible way to proceed. Ultimately, progress towards social protection for all is elapsing too slowly to protect people against ordinary life-cycle risks and the looming challenges ahead, whether driven by the climate crisis or by other factors.

Many countries have made significant progress in strengthening their social protection systems (ILO 2021q). The massive policy response during the COVID-19 pandemic showed the power of social protection to contain crises and respond to human needs, with the large majority of countries implementing social protection measures.

However, many of these measures were only temporary (Orton, Markov and Stern-Plaza 2024). Not making them permanent was a lost opportunity to strengthen systems, especially in light of the overwhelming evidence that countries with comprehensive systems already in place could respond quickly and more effectively to a massive covariate shock (ILO 2021q).

For social protection systems to effectively address both life-cycle and climate-related risks, they need to get the basics right: it is necessary to make sure that (a) everyone is protected and able to access benefits when needed (section 3.2), (b) this protection is comprehensive and adequate (section 3.3), (c) systems are sustainably and equitably financed (section 3.4), and (d) the essential institutional and operational capacities are established and adapted to address climate and transition impacts (section 3.5).

.3.2 Coverage trends: Positive but too slow

3.2.1 Global and regional overview of social protection coverage (SDG indicator 1.3.1)

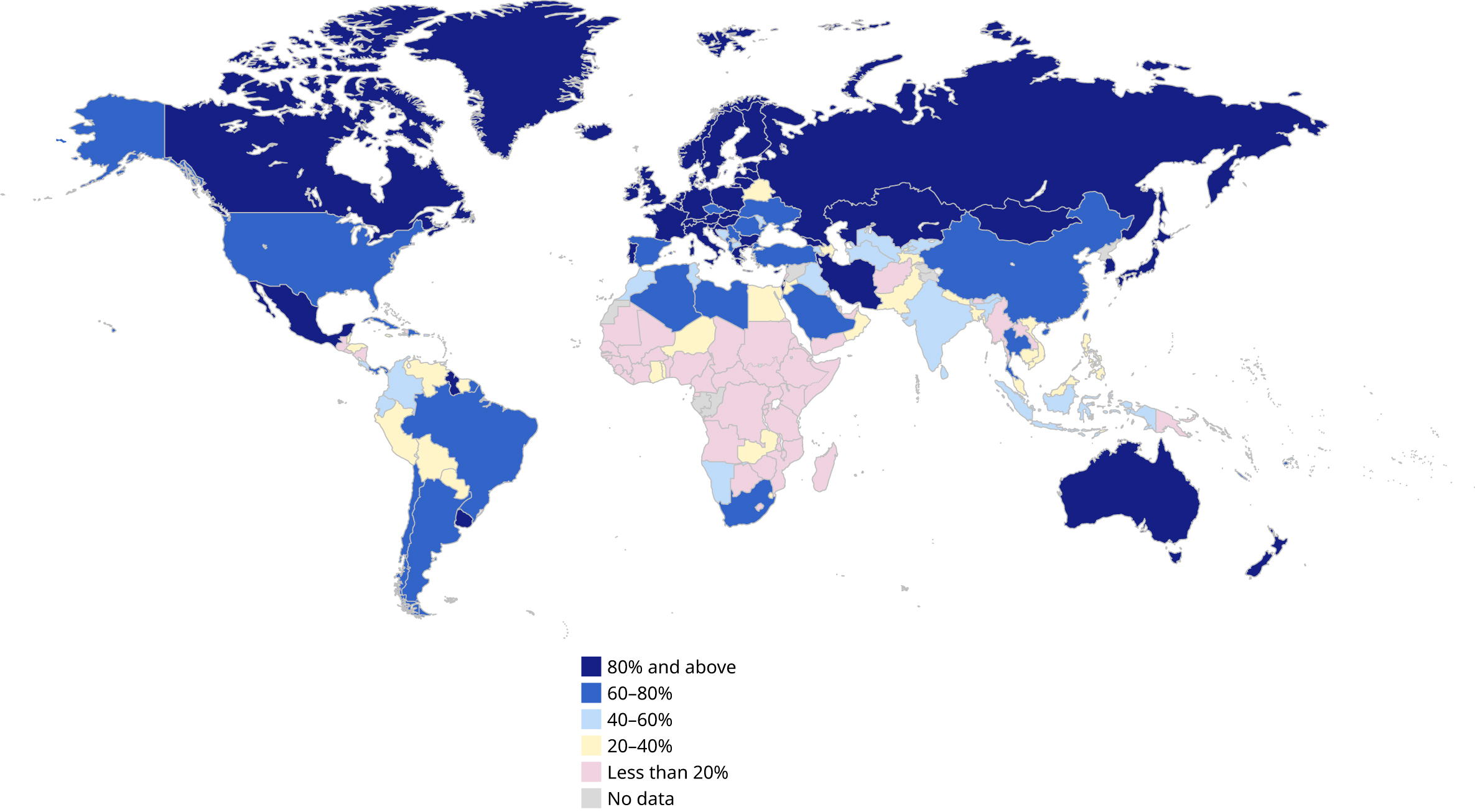

The world has surpassed an important milestone: for the first time, more than half the world’s population (52.4 per cent) are covered by at least one social protection benefit, representing an increase of 9.6 percentage points since 2015 (see figures 3.1 and 3.2). Yet, the remaining 47.6 per cent – as many as 3.8 billion people – are left unprotected, without access to any social protection.

It is particularly concerning that in the 50 countries most vulnerable to climate change, only 25 per cent of the population is covered, leaving 2.1 billion people unprotected (see figure 2.3b). In the 20 most vulnerable countries, less than one in ten persons is covered (8.7 per cent), leaving 364 million persons to fend for themselves. This prompts great concern and shows that much of the world is unprepared and the most vulnerable populations on the front line of the climate crisis are woefully unprotected.

The world is on a divergent course (see figure 3.2). High-income countries continue to close protection gaps, making steady and substantial progress, with coverage increasing over the period 2015–23 from 81.0 per cent to 85.9 per cent. Lower-middle-and upper-middle-income countries have achieved marked improvement in coverage rates, which have increased from 20.9 per cent to 32.4 per cent and 56.5 per cent to 71.2 per cent, respectively. However, in low-income countries, coverage has barely moved, with only 9.7 per cent of the population protected, which is deeply concerning. In the face of widespread repercussions of climate change and life-cycle risks, the extension of coverage should be of highest priority, which will require international support, including a more enabling global financial architecture that can support national efforts in expanding fiscal space.

Figure 3.1 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective social protection coverage by at least one cash benefit, 2023 or latest available year (percentage)

Disclaimer: Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO. See full ILO disclaimer.

Sources: ILO estimates, World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

While progress made since 2015 is promising, it remains too slow. At the current rate, it would take another 49 years – until the year 2073 – for everyone to be covered by at least one social protection benefit, and even longer to reach adequate and comprehensive protection. Accelerating progress is essential for current and future generations, and the experiences of countries that have made swift progress in a short space of time – such as Finland in the early twentieth century and more recently China, Oman, South Africa and Zambia – demonstrate that it is possible. Though, this requires significant investment, determination and political will from both national policymakers and international actors.

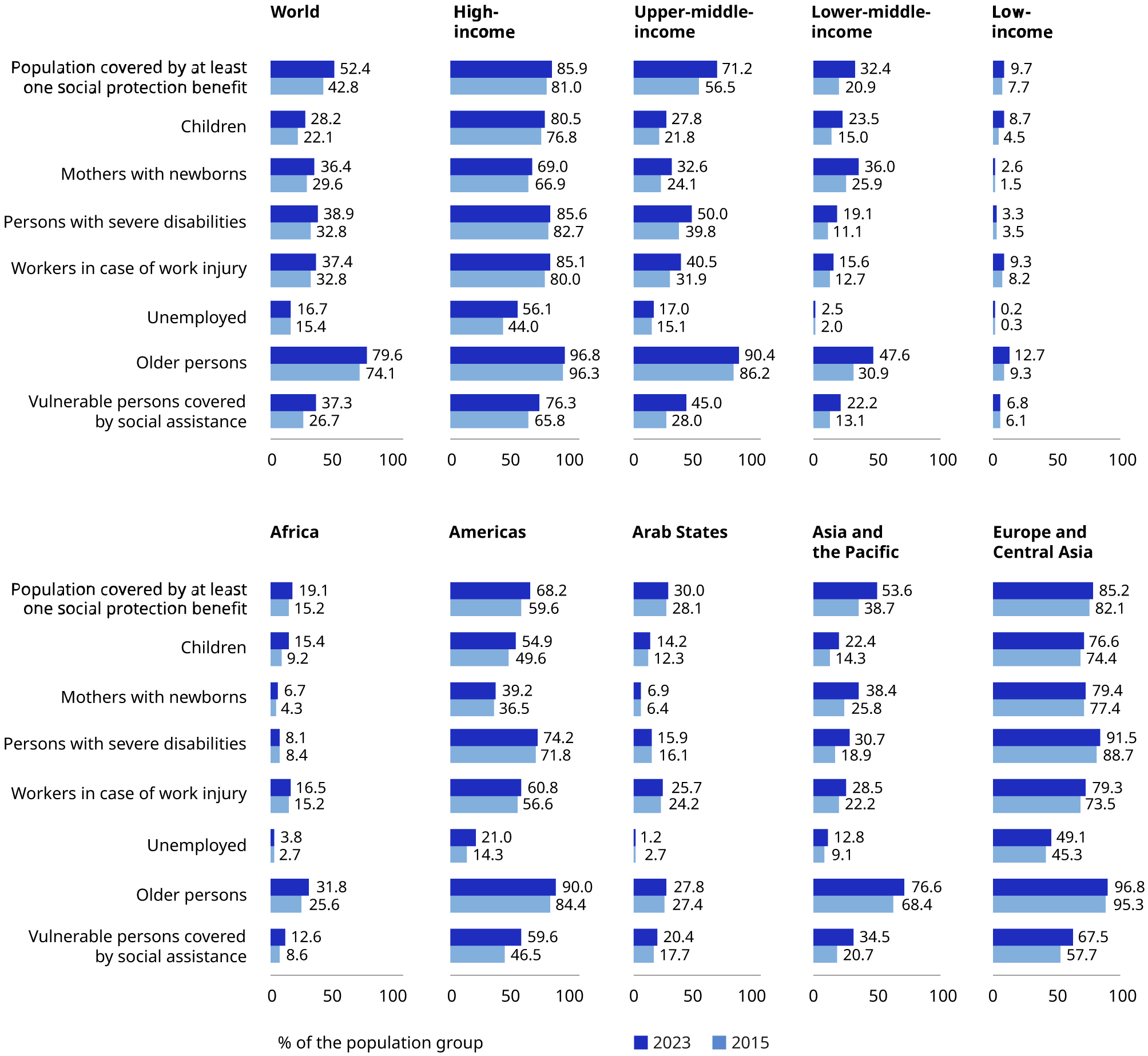

Global and regional coverage trends between 2015 and 2023 (including SDG indicator 1.3.1) show some, yet still insufficient, progress, leaving billions unprotected or inadequately protected (see figures 3.2 and 3.3).

-

28.2 per cent of children globally receive a family or child benefit, up by 6.1 percentage points since 2015 (section 4.1).

-

36.4 per cent of women with newborns worldwide receive a cash maternity benefit, up by 6.8 percentage points (section 4.2.2).

-

38.9 per cent of people with severe disabilities receive a disability benefit, up by 6.1 percentage points (section 4.2.5).

-

37.4 per cent of people enjoy employment injury protection for work-related injuries and occupational disease, up by 4.6 percentage points (section 4.2.4).

-

16.7 per cent of unemployed people receive unemployment cash benefits in the event of job loss, up by 1.3 percentage points (section 4.2.6).

-

79.6 per cent of people above retirement age receive a pension, up by 5.5 percentage points (see section 4.3).

-

37.3 per cent of vulnerable persons are covered by social assistance, up by 10.6 percentage points (see section 3.2.3).

-

60.1 per cent of the global population is covered by social health protection, stalling since 2015 (see section 4.4).

Across regions, there has been an uneven increase in effective coverage rates between 2015 and 2023 (figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 SDG indicator 1.3.1: Effective social protection coverage, global, regional and income-level estimates, by population group, 2015 and 2023 (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation, and Annex 5 for more detailed data. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population group. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

Figure 3.3 Effective coverage: number of covered and uncovered persons by social protection branch, 2023

Source: ILO estimates; World Social Protection Database, Social Security Inquiry; ILOSTAT and UNWPP.

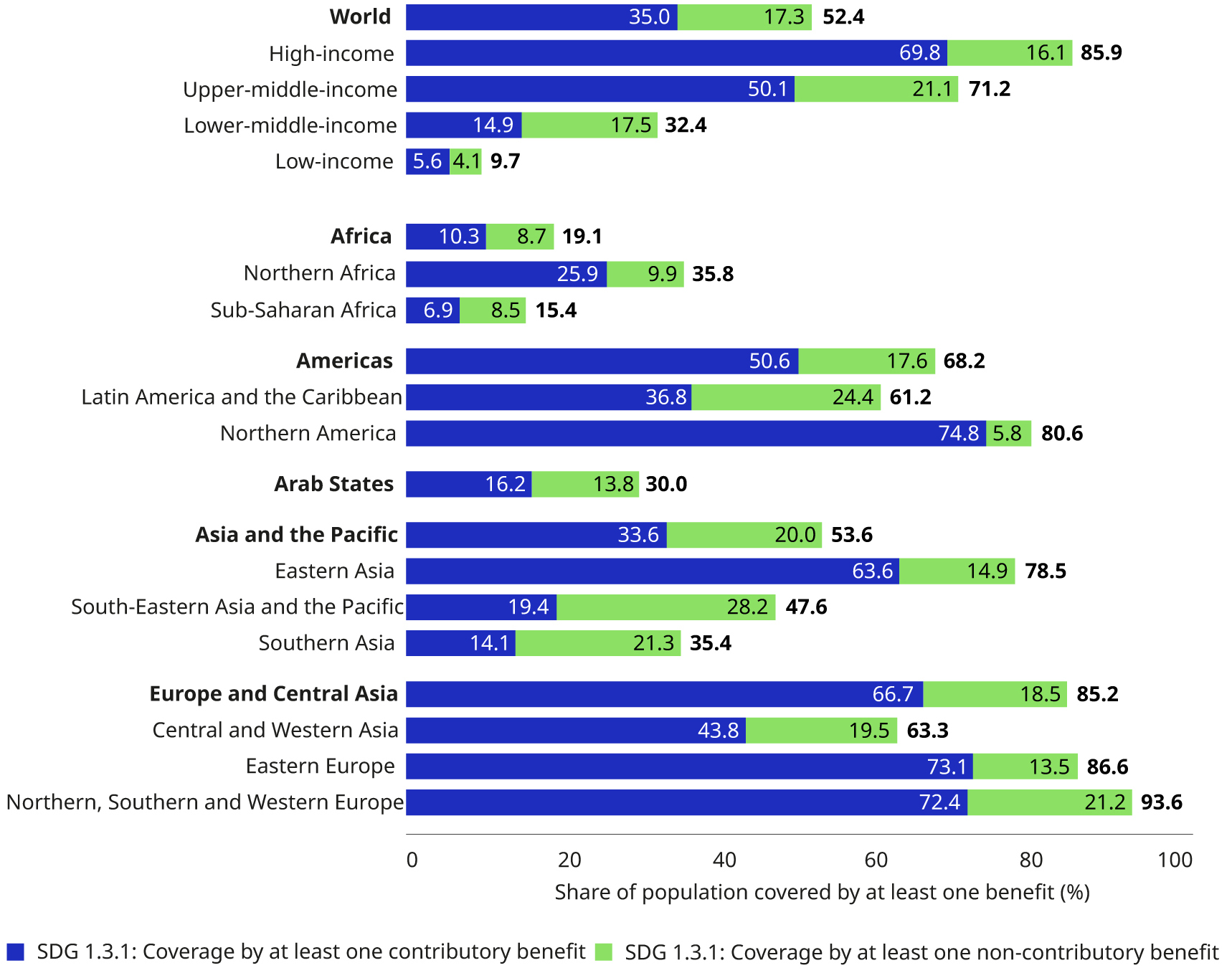

Figure 3.4 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective social protection coverage by at least one cash benefit, global, regional and income-level estimates for contributory and non-contributory benefits, 2023 (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions. Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond to the sum of the separate figures.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

-

Africa has achieved only modest progress with an increase of coverage rates from 15.2 to 19.1 per cent of the population. Given that African countries face pronounced vulnerabilities to the climate crisis, it is concerning that more than 80 per cent of their population must fend for themselves without any social protection. This does not bode well for Africa’s readiness to cope with the climate crisis.

-

The Europe and Central Asia region already had relatively comprehensive and mature social protection systems, and increased coverage from 82.1 to 85.2 per cent. Nonetheless, there are still important gaps to close that are indicative of a substantial vulnerable population who is insufficiently covered.

-

The Americas have achieved a more substantial increase in effective coverage from 59.6 to 68.2 per cent, which reflects long-standing efforts to extend coverage to previously uncovered categories of the population.

-

The Arab States’ anaemic increase in coverage from 28.1 to 30.0 per cent of the population provokes concern, especially given that they are prone to some of the most severe consequences of the climate crisis and face protracted conflict and displacement.

-

The Asia and Pacific region has achieved the largest increase in coverage from 38.7 to 53.6 per cent. This needs to be further accelerated to increase the region’s capacity to tackle the challenges of climate change, informality and population ageing.

Worldwide, 35.0 per cent of the population are covered by contributory social protection mechanisms, and 17. 3 per cent by non-contributory mechanisms (largely financed by taxes) (figure 3.4), with variation across regions and country income levels. While contributory mechanisms (mainly social insurance) account for the coverage of more than half of the population in high-income and upper-middle-income countries, they also play a significant role in low-income and lower-middle-income countries.

3.2.2 Coverage gaps for workers: Unpacking the “missing middle”

One of the reasons for persistent coverage gaps is the fact that many workers and their families are neither covered by contributory mechanisms (especially social insurance) nor by non-contributory (usually tax-financed) mechanisms – they fall through the cracks of both types of mechanisms, and thus are often referred to as the “missing middle”, leaving them vulnerable.

Some categories of workers are less likely to be covered by social insurance than others, for instance, workers on temporary contracts (especially those with very short contracts or those in casual labour), in part-time work (especially those with very few and irregular hours), workers on digital platforms and those in self-employment, depending on national policy and legal frameworks and their implementation. As a result, many of these workers find themselves in informal employment (ILO 2023w), which further contributes to high vulnerability.1

Extending social insurance coverage to these workers usually provides for a higher level of protection compared to non-contributory benefits. Based on the principles of risk sharing and solidarity, social insurance schemes are collectively financed through workers’ and/or employers’ contributions that are proportionate to contributory capacities. Where these are insufficient, governments often subsidize or otherwise facilitate coverage, including for those who are temporarily unable to contribute because of unemployment, care responsibilities or illness (ILO 2021b). Social insurance directly contributes to the formalization of employment; for tax-financed benefits the link is less direct, but they still contribute to facilitating transition from the informal to the formal economy (ILO 2021b).

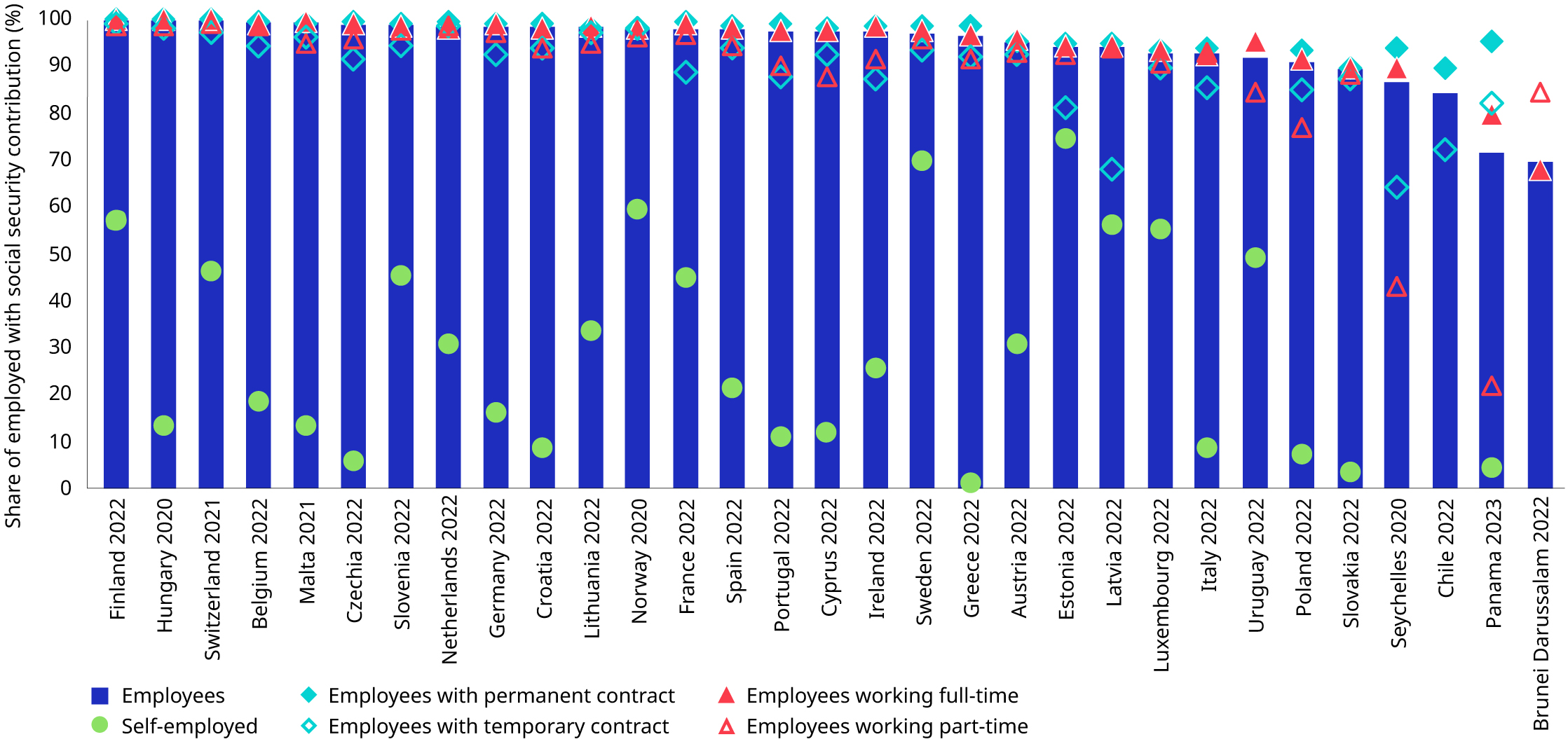

Recent labour force survey data analysis (Bourmpoula et al., forthcoming) demonstrates significant variation in social security coverage across countries, which suggests that extension policies make a difference (see figure 3.5). While, employees are generally more likely to contribute to social security than self-employed workers, several countries, including Brazil, Estonia, Sweden, Türkiye and Uruguay, have covered self-employed workers through adapted mechanisms, and have achieved significant levels of coverage (ILO 2021f; ILO and WIEGO, forthcoming; Spasova et al. 2021). Whereas, in most countries, employees working on permanent contracts are more likely to contribute to social security than employees with temporary contracts, in others (for example, Croatia, El Salvador and the Netherlands), the difference is negligible. Similarly, in Armenia, Bulgaria, Uruguay and Viet Nam, social security coverage of part-time workers is close to that of full-time workers.

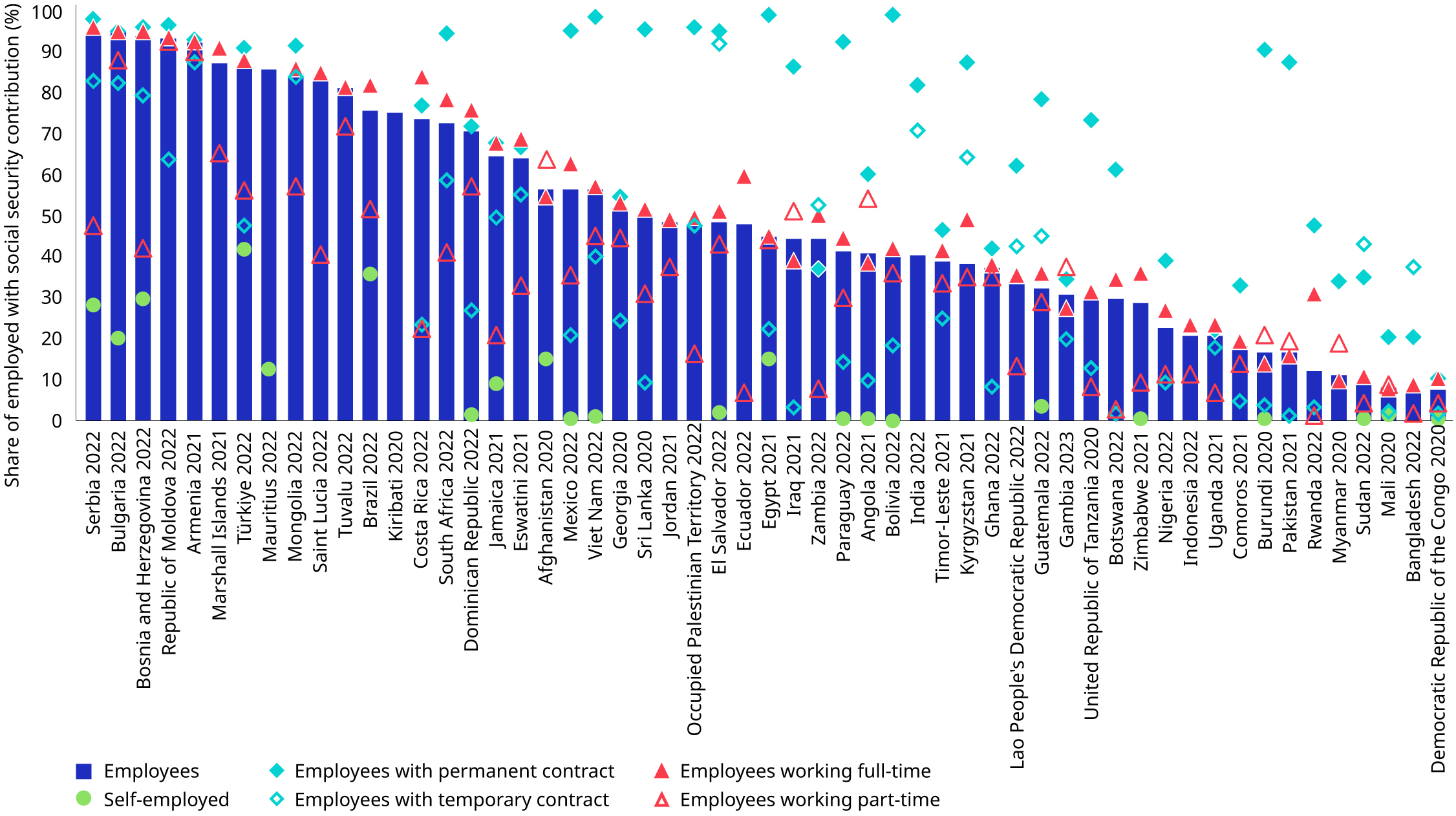

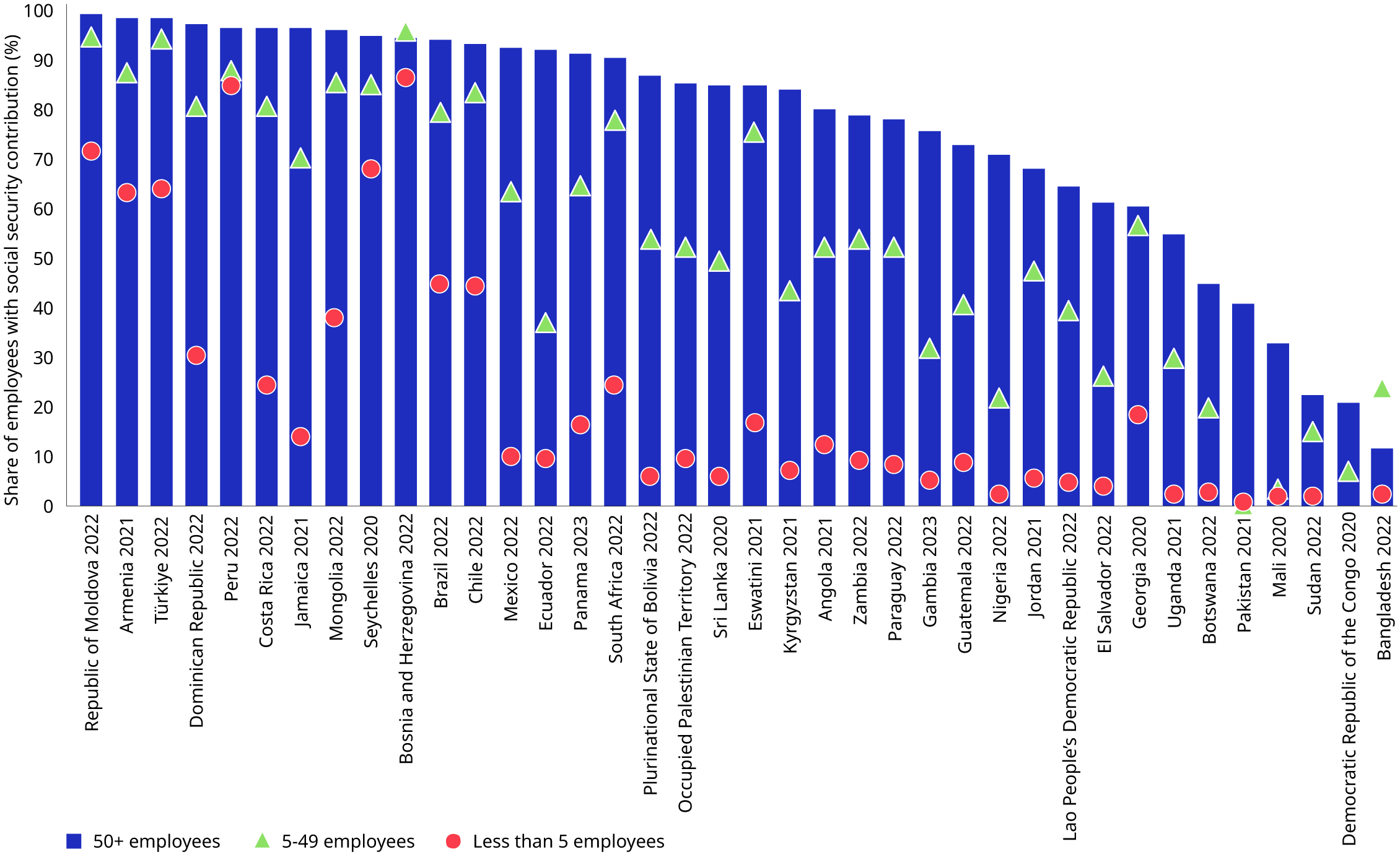

Another key factor that influences social insurance coverage is enterprise size (figure 3.6). In almost all countries, social security coverage of employees in smaller enterprises is lower than for those in larger enterprises. Low coverage is a particular challenge for enterprises with less than five workers, often due to exclusion from legal frameworks or low compliance. Yet, some countries have also achieved high coverage levels for workers in such enterprises, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Peru and the Republic of Moldova (ILO 2021g; Gaarder et al. 2021).

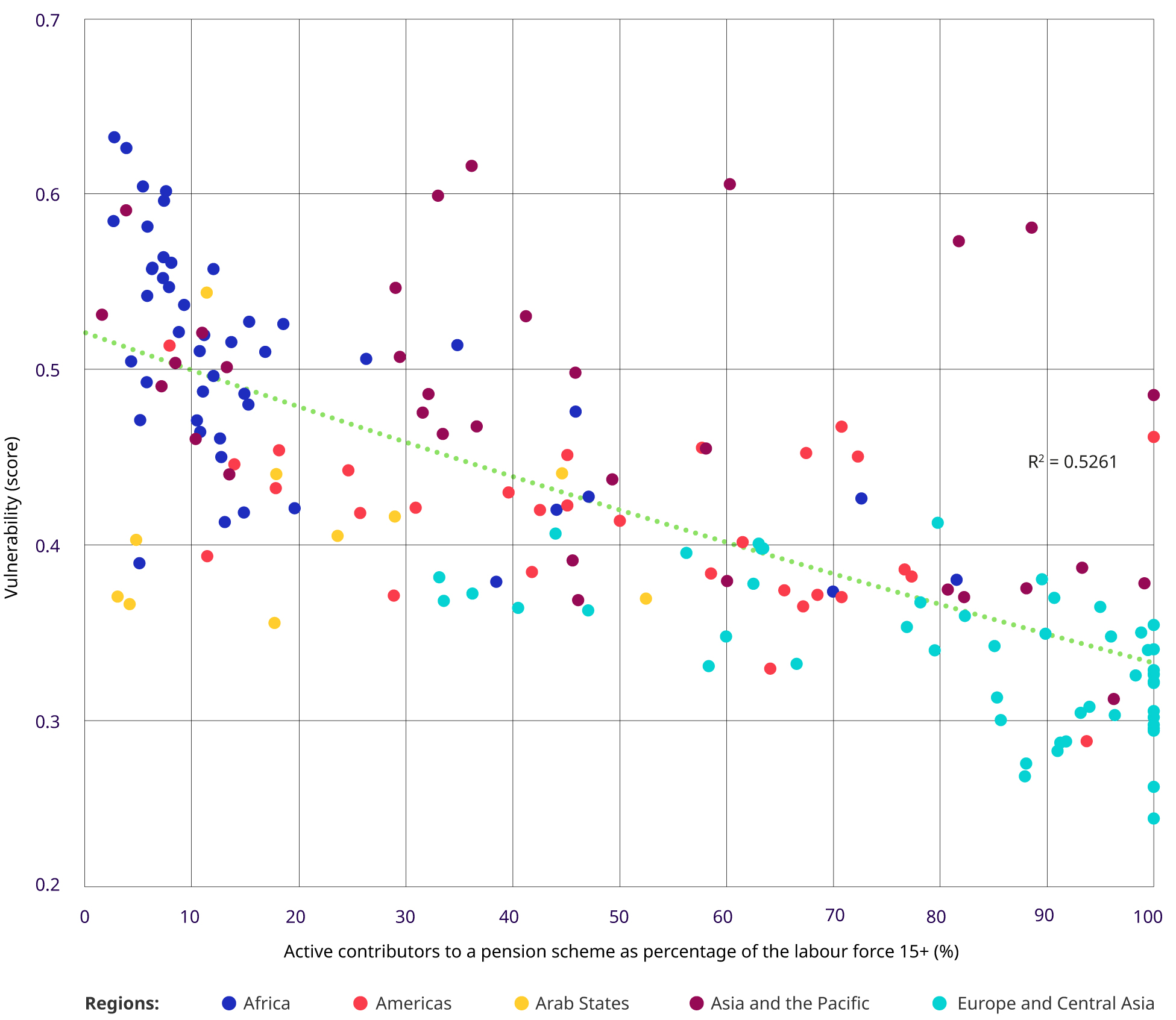

Yet, more needs to be done to achieve universal social protection. A just transition can only succeed if workers affected by climate change and climate policies can access adequate benefits, including those in new and emerging sectors. In countries with high levels of vulnerability to climate change, particularly in Africa, the Arab region and parts of Asia and the Pacific, the large majority of workers remain legally or de facto excluded from social insurance coverage that would provide them with support in case of climate shocks or to seize new opportunities offered by the green economy (see figure 3.7). Furthermore, they are likely to be excluded from tax-funded or other non-contributory mechanisms, often limited to those outside the labour market.

Figure 3.5 Employed population contributing to social security, by status in employment, type of contract and working-time arrangement, selected countries and territories, latest year (percentage)

(a) High-income countries

(b) Middle- and low-income countries and territories

Source: Based on labour force survey data, ILO Harmonized Microdata Collection, ILOSTAT. For more information, see Bourmpoula et al. (forthcoming).

Figure 3.6 Employees contributing to social security, by size of the enterprise, selected countries and territories, latest year (percentage)

Source: Based on labour force survey data, ILO Harmonized Microdata Collection, ILOSTAT. For more information, see Bourmpoula et al. (forthcoming).

As many newly created jobs may be in sectors and occupations with traditionally high levels of non-coverage and informality, it will be essential that workers in all types of employment, including those in self-employment, enjoy decent work, including adequate social protection to ensure both income security and access to essential healthcare (ILO 2021m; 2023c).

Guaranteeing access to social security is essential in ensuring that workers and enterprises are sufficiently resilient in responding to climate change impacts and to support a just transition to environmentally sustainable economies, as well as the formalization of employment (Bischler et al. forthcoming; ILO 2021i).

Extension strategies will need to simultaneously address the legal, financial, administrative and information barriers, while investing in raising awareness about the importance of social protection and improving governance, delivery mechanisms, and quality of benefits and services (ILO 2021i). Ensuring well-designed strategies that take into account the specific situations of workers, while at the same time avoiding fragmentation and exclusion, is a key condition for success in extending coverage to people not yet sufficiently covered, including workers in small and microenterprises, self-employed workers and entrepreneurs, and workers on digital platforms (ILO 2021p; 2024e; Behrendt, Nguyen and Rani 2019), with specific attention to gender equality and the inclusion of refugees (see box 3.1).

Figure 3.7 The relationship between a country’s vulnerability to climate change and the share of workers contributing to social security

Source: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index and ILO World Social Protection Database.

Given the high vulnerability of the agricultural sector to climate change, accelerating efforts to ensure effective access of agricultural workers to social protection is critical. Beyond addressing their life-cycle risks, social protection also increases resilience with regard to their economic risks (Asfaw and Davis 2018), especially where it is complemented by measures that:

-

facilitate the transition to more sustainable modes of agricultural production and climate-resilient livelihoods, as well as non-agriculture activities; and

-

support people dependent on natural resources in adapting their livelihoods and/or diversifying their income sources (ILO and FAO 2021; ILO 2023p; Bischler et al. forthcoming).

Likewise, as many jobs created in the circular economy are currently informal (ILO, Circle Economy and S4YE 2023), additional efforts are needed to extend social security to workers in the sector, including waste pickers (Cappa et al. 2023; Chikarmane and Narayanan 2023).

Box 3.1 The Estidama++ Fund in Jordan

|

Established through a joint effort by the Social Security Corporation and the ILO, the Estidama++ Fund is designed in alignment with international labour standards, as part of a national strategy for extending the coverage of the national social security scheme (Social Security Corporation) to vulnerable populations (ILO 2022d). The project aims to reach more than 32,000 Jordanians and non-Jordanians, with special focus on Syrian refugees and women, providing contribution subsidies and coverage rewards to facilitate their long-term enrolment in the social insurance scheme (ILO 2023k). The Estidama++ Fund addresses the affordability constraints faced by informal workers who have limited contributory capacity, supporting wage workers in micro, small and medium-sized enterprises and self-employed workers to register in the Social Security Corporation by subsidizing their contributions for 12 months and offering other incentives for coverage (ILO 2023k).1 1 For more information, see https://www.ilo.org/beirut/projects/WCMS_888951/lang--en/index.htm, https://www.ilo.org/beirut/media-centre/news/WCMS_899572/lang--en/index.htm. |

3.2.3 Protecting migrants

As many migrants are acutely and directly impacted by the climate crisis (ILO 2022g), enhancing social protection for them is particularly urgent. Strengthening social protection systems in both countries of origin and destination, and ensuring inclusive and effective access for migrants is key to ensure that people are covered against the financial risks they may face throughout their lives, including risks incurred due to climate-induced migration (ILO, ISSA and ITCILO 2021).

Migrant workers may have no or limited access to social protection schemes because of their nationality, migration status, duration or type of residence or employment, or the sector in which they work (ILO, ISSA and ITCILO 2021). Ensuring equal treatment with nationals and extending coverage to workers in sectors and occupations with a high proportion of migrant workers, such as agriculture or domestic work, helps ensure their effective access to social protection (ILO 2023l). Moreover, as migrant workers are often over-represented in carbon-intensive sectors, ensuring equality of treatment between nationals and non-nationals in transition measures is also essential (ILO 2024d).

Some countries have incorporated the right to social security for all in their constitution (Bangladesh and Colombia), while others have included non-nationals in their social security laws (Costa Rica, Jordan, Poland and Sudan).

However, despite commendable progress, in many countries, non-nationals do not benefit from comprehensive social protection, because (a) they are excluded from social assistance programmes or certain branches (such as medical care, unemployment insurance and family benefits), (b) certain groups are excluded, notably migrant domestic and agricultural workers, or (c) their legal inclusion does not translate into their effective access (see box 3.2).

Facilitating bilateral discussions on the portability of social protection entitlements in situations in cross-border mobility, including those due to the transition to environmentally sustainable economies and climate change impacts, is particularly important for a just transition (ILO 2015c; 2024d). There has been an exponential increase in the number of social security agreements worldwide (ISSA 2022), and the development of regional agreements and policy frameworks as part of regional integration processes (Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and Southern African Development Community (SADC)) is also evolving. Yet, at the national level, only 20 per cent of the countries with the highest migrant population worldwide have legal provisions on equality of treatment between nationals and non-nationals.

Box 3.2 Coverage of migrants in Gulf Cooperation Council countries

|

Interesting developments have emerged in Gulf Cooperation Council countries, where legal provisions for private sector workers are still relatively weak both for citizens and migrants, who constitute the majority of the workforce. Most countries have legislation that cover migrant workers, but for certain risks – sickness, maternity and employment injury – provided through employer liability mechanisms (ILO 2023s). Moreover, migrants historically have tended to access public health systems. However, there has recently been a shift to refer them to mandatory private insurance for non-emergency care. Yet, some encouraging reforms are under way in Oman to implement a social insurance scheme that covers sickness, maternity and employment injury including for migrants (ILO 2023i). |

3.2.4 Social assistance coverage for vulnerable groups

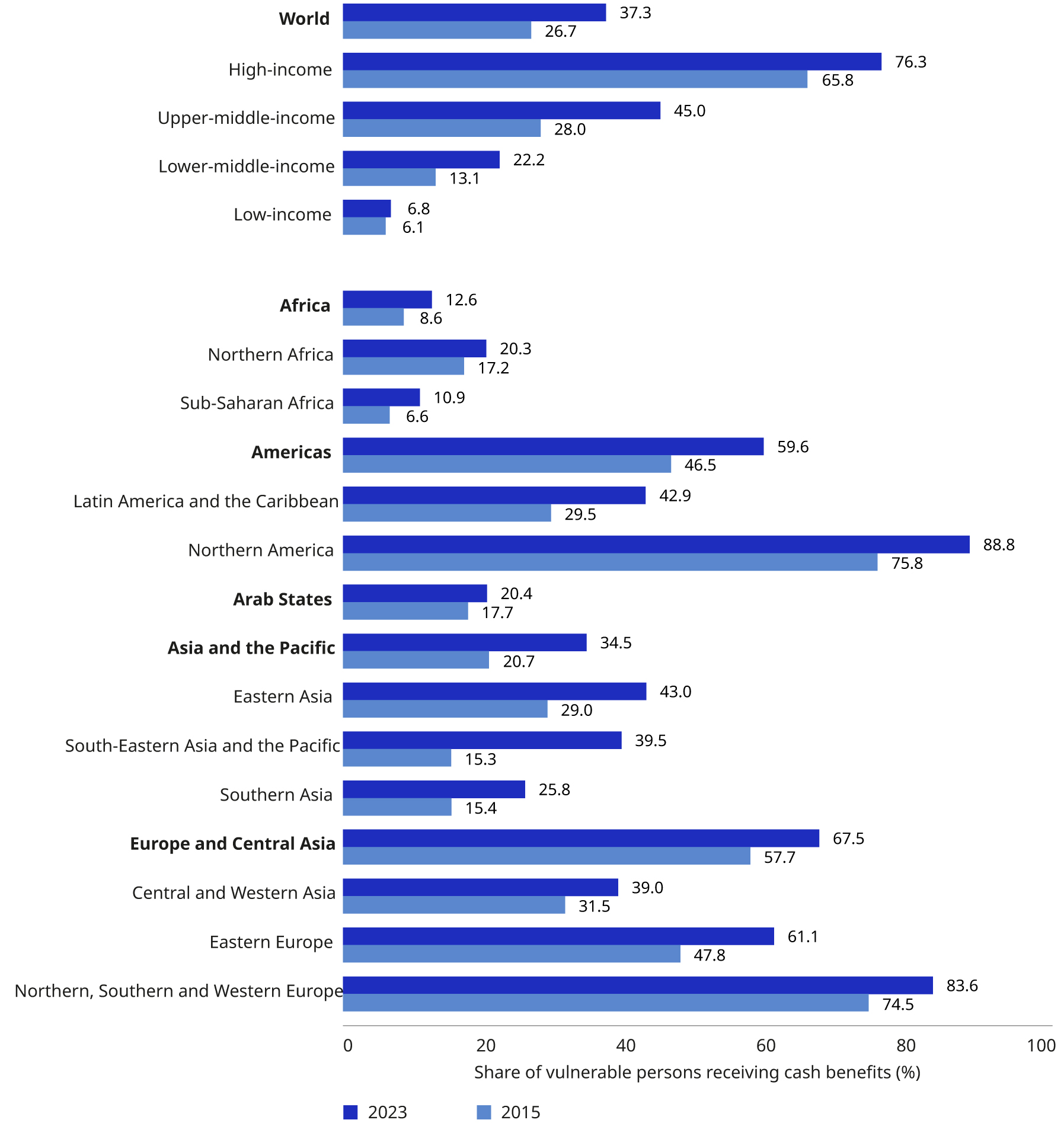

For people not covered through social insurance, it is important to note that in its absence, social assistance or other non-contributory cash benefits play an essential role in ensuring at least a basic level of social security. Globally, coverage has increased from 26.7 per cent to 37.3 per cent of vulnerable persons since 2015 (see figure 3.8).2 This increase can be interpreted in different ways. The positive reading is that it represents an improvement in benefits provided to vulnerable people, possibly due, in part, to the temporary policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic (ILO 2021q). However, a more cautious interpretation is that the higher population coverage stems from increased needs due to increasing poverty, vulnerability and decent work deficits, rather than a genuine increase in the quality of social protection.

In either case, more efforts are needed to ensure a solid social protection floor as part of universal social protection systems, leaving no one behind. In addition to cash benefits, in-kind benefits can also play an important complementary role in reducing vulnerability (see box 3.3), especially if well coordinated with cash benefits. Moreover, greater efforts are needed to facilitate transitions from social assistance into decent employment covered by social insurance, which provides higher levels of protection and relieves pressure on tax-financed social assistance schemes as a last-resort protection mechanism.

Figure 3.8 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective coverage for protection of vulnerable persons: Share of vulnerable persons receiving cash benefits (social assistance), by region, subregion and income level, 2015 and 2023 (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

Box 3.3 In-kind social protection: India’s Targeted Public Distribution System

|

India’s Targeted Public Distribution System is one of the world’s largest legally binding social assistance schemes providing in-kind food security to about 800 million people. Operated with end-to-end digitalization and transparency measures, it ensures efficient foodgrain delivery. Its national portability enables access for beneficiaries from other federal states. The Targeted Public Distribution System provides 35 kilograms of foodgrain per month to the most vulnerable households, while other qualifying beneficiaries receive 5 kilograms per month. From 2013 to 2022, the Targeted Public Distribution System provided rice, wheat and millet at subsidized rates and, since 2023, these products are free until 2028. The Targeted Public Distribution System entitlement is equal to around half of the average monthly per capita cereal consumption in India. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government nearly doubled the monthly food grain entitlements for its 800 million beneficiaries by providing an additional 5 kilograms of foodgrain for each beneficiary free of charge for 28 months until December 2022. Studies show that the scheme protects people from surging food prices (Negi 2022). After some reforms, and improved coverage, the scheme reduces poverty and food insecurity (Drèze and Khera 2013; Thomas and Chittedi 2021). The Targeted Public Distribution System also significantly prevented extreme poverty levels from worsening in India between 2020 and 2021 (Bhalla, Bhasin and Virmani 2022). Its distribution of fortified rice and inclusion of millet have further boosted its capacity to combat undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. |

3.2.5 Gender gaps: progress towards gender-responsive social protection systems

Social protection coverage still shows significant gender inequalities, with the effective coverage of women by at least one cash social protection benefit lagging behind that of men by 4.5 percentage points (50.1 and 54.6 per cent respectively), especially in middle-income countries (see figure 3.9, first panel). A full picture of gender gaps is, however, difficult to obtain given a persistent lack of data. Only 20 countries produce complete sex-disaggregated data for child benefits, disability benefits, employment injury benefits and old-age pensions.

Clearly, there is a long way to go in closing gender gaps in social protection. At the same time, social protection policies hold great potential to enhance gender equality and help realize women’s rights (UN Women, forthcoming; ILO 2021). Yet, in practice, social protection policies have not always addressed the following gender-specific risks and challenges in relation to gender equality: gender-based inequalities in employment, the unequal division of unpaid care work, and gender-specific risks across the life cycle (Razavi et al., forthcoming a; ILO 2024a). These three factors are interrelated and shape how women engage in paid and unpaid work, which has important knock-on effects on their social protection coverage.

An example is the coverage for old-age pensions, for which the most comprehensive data disaggregated by sex are available for a large number of countries (figure 3.9). The data show that, in most regions and subregions, older women are less likely to receive a contributory pension than men (second panel) but, in many cases, they are more likely to receive a non-contributory (tax-financed) pension (third panel).

Similarly, women of working age tend to be less likely than men to contribute to a pension scheme across all regions if measured as a percentage of the working-age population (fourth panel), due to their lower participation in employment (sixth panel).

Yet, if measured as a percentage of the labour force (fifth panel), the picture is much less clear:

-

In some parts of the world (for example, in sub-Saharan Africa, Southern Asia and in Central and Western Asia, and in low-and middle-income countries generally), women in the labour force are less likely to contribute than men. This is especially the case when they work in sectors and occupations associated with high levels of vulnerability, such as agriculture or domestic work (ILO 2023w).

-

Elsewhere, women in the labour force are roughly on par with men (for example, in Eastern Asia) or even more likely to contribute than men (for example, in Northern Africa, the Arab States, and Latin America and the Caribbean, and generally in high-and upper-middle-income countries), where women often work in the public sector, clerical jobs, manufacturing (for example, the garment sector), health and education.

Figure 3.9 Gender gaps in effective social protection and pension coverage: SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective social protection coverage, beneficiaries

Notes: Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population aged 65 and over for old age beneficiaries; by working-age population and labour force aged 15 and over for the contributors; and by working-age population for the labour force participation rates.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

These patterns call for a more nuanced analysis of social security coverage of women that examines more thoroughly how gendered employment patterns are mirrored, mitigated or exacerbated in social protection systems. Analysing the data from a life-course perspective provides further insights into the impact of employment patterns on social security coverage by age (see box 3.4).

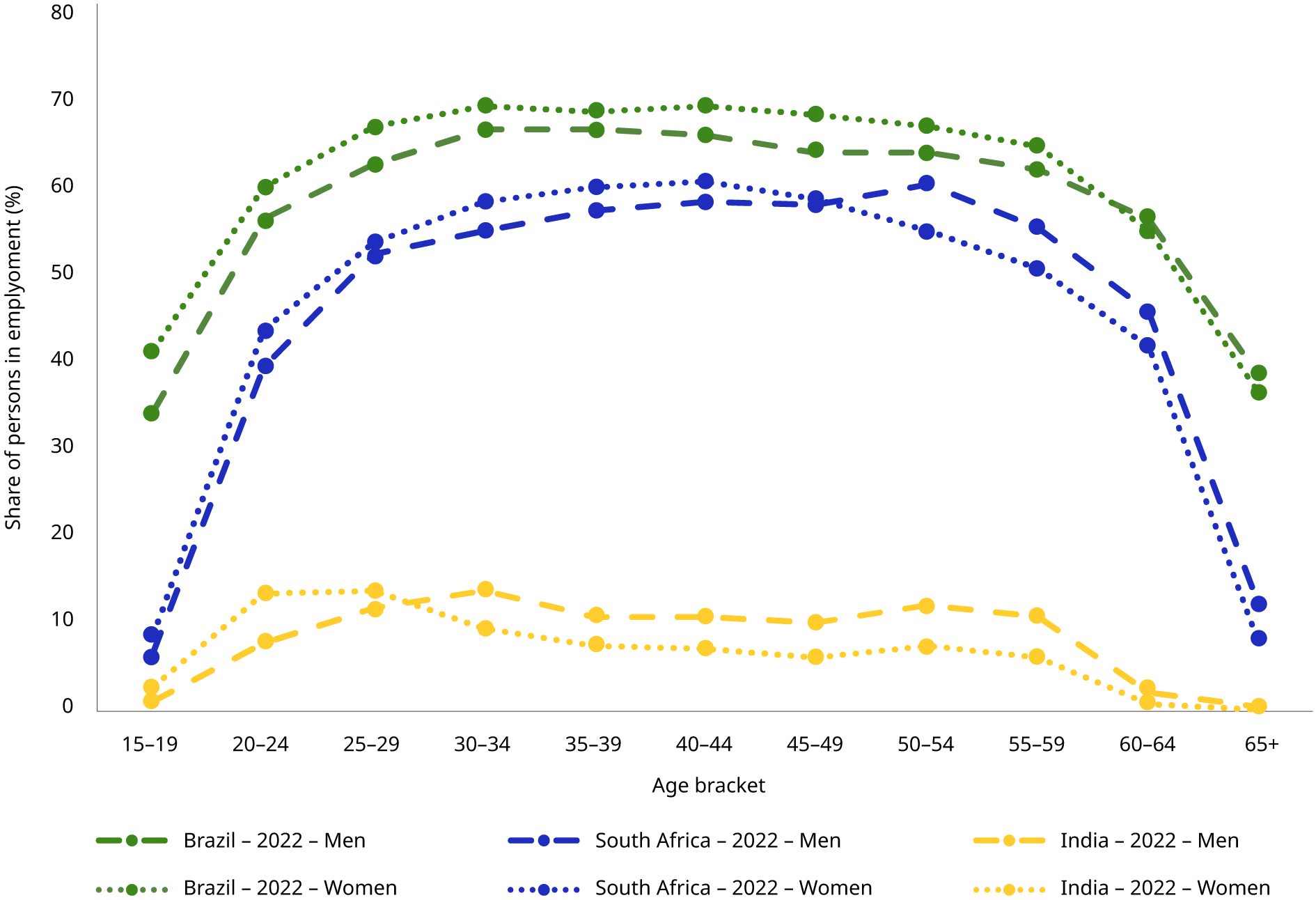

Box 3.4 Life-course patterns in social security coverage in Brazil, India and South Africa

|

A recent analysis of social security coverage by age in Brazil, India and South Africa found that, for people in employment (including self-employment), gender differentials are smaller than what might have been expected overall, yet with intriguing life-course patterns (ILO and ISSA 2023). In India and South Africa, coverage rates for young women are higher than for men up to a certain age, then their coverage rates drop below those of men after around 30 years in India and around 40 years in South Africa. The drop in coverage for prime-age women, at least in India, may reflect the impact of family structure and motherhood on their employment patterns: women shift to more “flexible” work arrangements for care-related reasons, which also carries a penalty in terms of social security coverage. In contrast, Brazil displays higher and relatively stable coverage rates for both women and men in their prime age, and women are more likely to contribute than men for almost all age groups. Figure B3.4 Share of persons in employment who contribute to a pension scheme, by sex and age, selected countries, latest available year (percentage)

|

Source: ILO and ISSA (2023).

Box 3.5 What is gender-responsive social protection?

|

Gender-responsive social protection goes beyond simply acknowledging gender dynamics and responding to gender-specific risks. It strives to transform the structural constraints and discriminatory social norms that drive gender inequalities. Thus, both the design and implementation of social protection policies must take into account the structural impediments women and girls face – occupational segregation, gender pay gaps and unequal sharing of care responsibilities. Such impediments should be understood in tandem with gender-specific risks and vulnerabilities, both across the life cycle and in case of climate shocks and disasters in order to achieve positive gender equality outcomes. |

Source: Razavi et al. (forthcoming a).

This comparative evidence demonstrates the importance of a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of gender inequalities in employment and access to social insurance. It also highlights the importance of gender-responsive policy reforms to extend social insurance coverage to those not yet covered, especially those in vulnerable forms of employment (ILO 2021i).

Closing coverage gaps for women is urgent to prime social protection systems for a just transition, as environmental crises often impact women more strongly than men. Together with labour market, employment, health and care policies, gender-responsive social protection policies (see box 3.5) play a crucial role in achieving gender equality in response to the climate crisis.

While tax-financed benefits play a central role in guaranteeing at least a basic level of social security for all as part of a social protection floor, social insurance coverage is also essential, as it provides a much greater potential for broad risk sharing, redistribution and measures to offset gender inequalities in the labour market compared to other contributory mechanisms (ILO 2021q; Razavi et al., forthcoming a).

.3.3 Comprehensive and adequate social protection

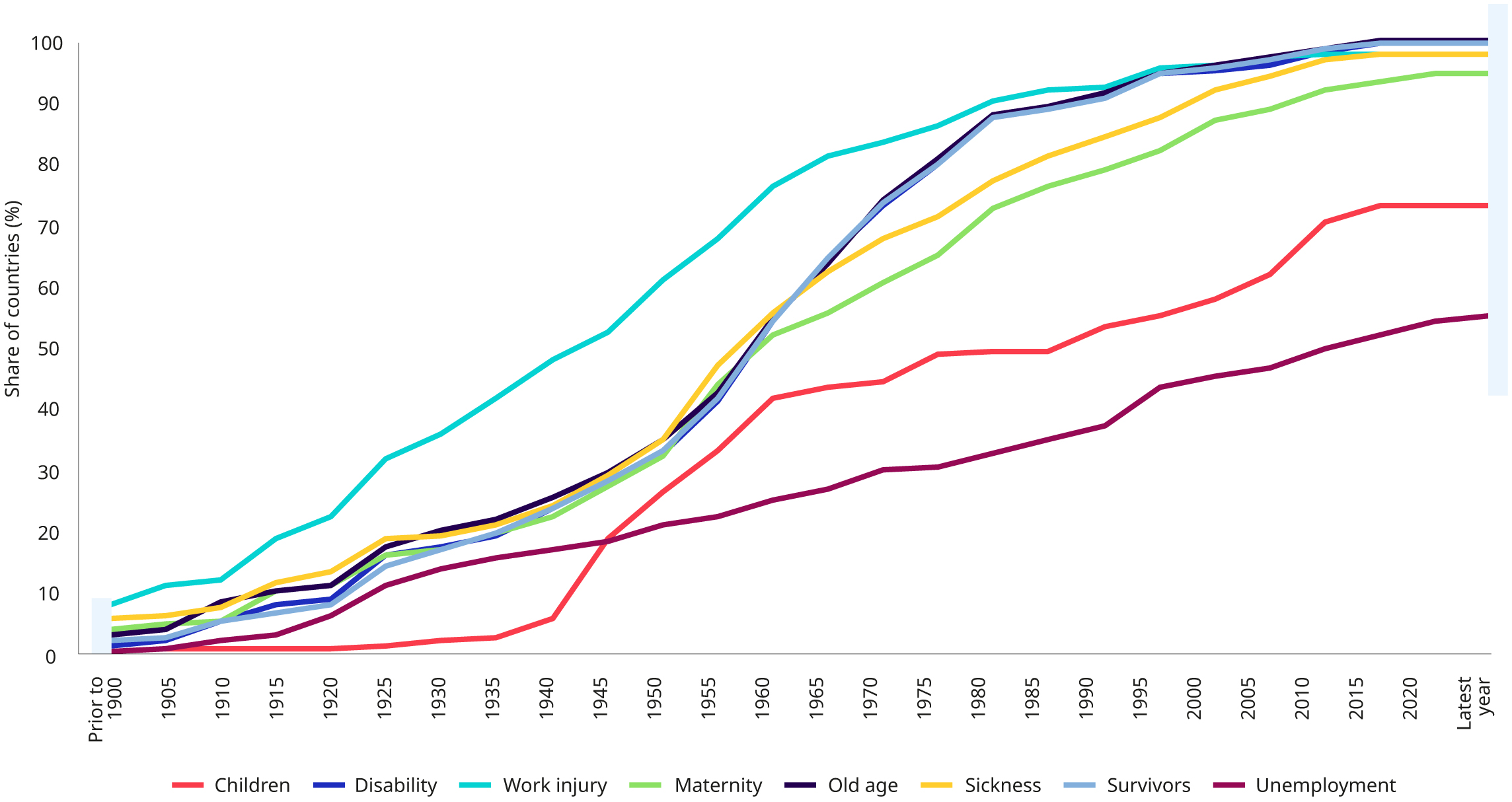

Although significant progress in achieving comprehensive social protection coverage has been made over the past century (figure 3.10), it has been slow. Large coverage and adequacy gaps still exist, especially in Africa and Asia, and this is mainly for two reasons. First, while most countries have legally-anchored schemes in place for most of the nine policy areas of Convention No. 102, in many cases these cover only a minority of their populations. Second, two policy areas are still lagging in terms of legal coverage: social protection schemes for children and unemployment protection. This is not surprising, as countries tend to build their systems sequentially, addressing different areas in varying order, depending on their national circumstances and priorities.3 Yet, these two areas account for major insecurities and would benefit from being given greater attention (see sections 4.1 and 4.2.6).

Figure 3.10 Development of social protection schemes anchored in national legislation by policy area, pre-1900 to 2023 (percentage of countries)

Notes: Based on the information available for 186 countries. The policy areas covered are those specified in Convention No. 102, excluding healthcare. The estimates include all schemes prescribed by law, including contributory and tax-financed schemes, as well as employer liability schemes.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

According to ILO estimates, only 33.8 per cent of the working-age population are legally covered by comprehensive social security systems, comprising an indicator calculated based on seven of the nine branches, namely maternity, sickness, unemployment, disability, work injury, survivors’ and old-age benefits (table 3.1). Thus, the large majority of the working-age population – 66.2 per cent, or almost 3.9 billion people – are not protected at all, or only partially protected. The gender gap is also significant: 28.2 per cent of working-age women are covered, compared to 39.3 per cent of their male counterparts. It is especially alarming to note that, in low-income countries, not one country has comprehensive social protection coverage. And even high-income countries have a considerable way to go to reach the milestone of accomplishing comprehensive legal coverage for all countries in this group.

Coverage is only truly meaningful and impactful if adequate benefit levels are provided, which can effectively prevent poverty, reduce vulnerability and maintain living standards, and are regularly reviewed and adapted to changes in the cost of living, in line with international social security standards (see Annex 3).

A social protection floor should guarantee a basic level of income security and access to healthcare to prevent hardship and enable a dignified life, defined on the basis of a transparent and participatory process. In respect of basic income security, Recommendation No. 202 (paragraph 8) refers to nationally defined minimum income thresholds, such as national poverty lines or income thresholds for social assistance. In respect of healthcare, it stipulates that persons in need of essential care should not face financial hardship and an increased risk of poverty when accessing it. In view of the multidimensional nature of poverty, it is essential that the provision of adequate and predictable cash benefits is considered alongside that of high-quality services, including education, housing, healthcare, long-term care, water and nutrition.

Table 3.1 Share of the working-age population aged 15 and over legally covered by comprehensive social security systems, by region, income level and sex, 2024 (percentage)

|

Region/Income group |

Share of the working-age population (total, %) |

Share of the working-age population (men, %) |

Share of the working-age population (women, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

World |

33.8 |

39.3 |

28.2 |

|

High-income |

63.1 |

66.2 |

59.9 |

|

Upper-middle-income |

51.1 |

59.1 |

42.7 |

|

Lower-middle-income |

15.2 |

20.7 |

9.4 |

|

Low-income |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

|

Africa |

6.7 |

10.0 |

3.5 |

|

Americas |

40.8 |

44.1 |

37.5 |

|

Arab States |

26.9 |

39.5 |

11.2 |

|

Asia and the Pacific |

35.3 |

42.1 |

28.2 |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

56.3 |

59.3 |

53.3 |

Notes: Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological changes. Calculations are based on the legal coverage by maternity, sickness, unemployment, disability, work injury, survivorship and old-age benefits. Child and family benefits and health coverage are not included for methodological reasons.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

For social protection systems to function optimally, they also need to provide higher levels of protection to as many people as possible, and as promptly as possible in line with international social security standards (see box 1.2). In practice, however, benefit levels in many social security schemes remain below minimum adequacy standards, as recent ILO research on pensions shows (see section 4.3.7 for more details). It is therefore urgent to ensure the adequacy of both contributory and non-contributory (tax-financed) benefits, especially as nearly 17.3 per cent of the global population depends solely on non-contributory benefits, often leaving them with minimal support on which to rely.

.3.4 Social protection expenditure and financing

3.4.1 Level and structure of social protection expenditure

Ensuring universal social protection relies heavily on securing and maintaining the required investment. This section delves into the expenditure patterns of social protection and provides estimates of the resources needed to address existing financing gaps.

In 2023, countries allocated 12.9 per cent of their GDP on average to social protection (excluding healthcare), alongside 6.5 per cent to healthcare, resulting in a total social protection expenditure of 19.3 per cent of GDP (see figure 3.11). However, there are significant disparities across national income groups. High-income countries dedicated approximately a quarter of their GDP to social protection, with 16.2 per cent directed towards income security and 8.7 per cent towards healthcare. As we move down the income spectrum, the share of GDP allocated to social protection declines markedly, with a mere 0.8 per cent for income guarantees and 1.2 per cent for healthcare in low-income countries. There are also notable discrepancies across regions. Countries in Northern, Southern and Western Europe allocate over a quarter of their GDP to social protection, while countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia only allocate 4.0 and 5.1 per cent, respectively.

Figure 3.11 Public social protection expenditure, 2023 or latest available year, domestic general government health expenditure, 2021, by region, subregion and income level (percentage of GDP)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by GDP. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions. Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond to the sum of the separate figures.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ADB, GSW, IMF; OECD; UNECLAC; WHO, national sources.

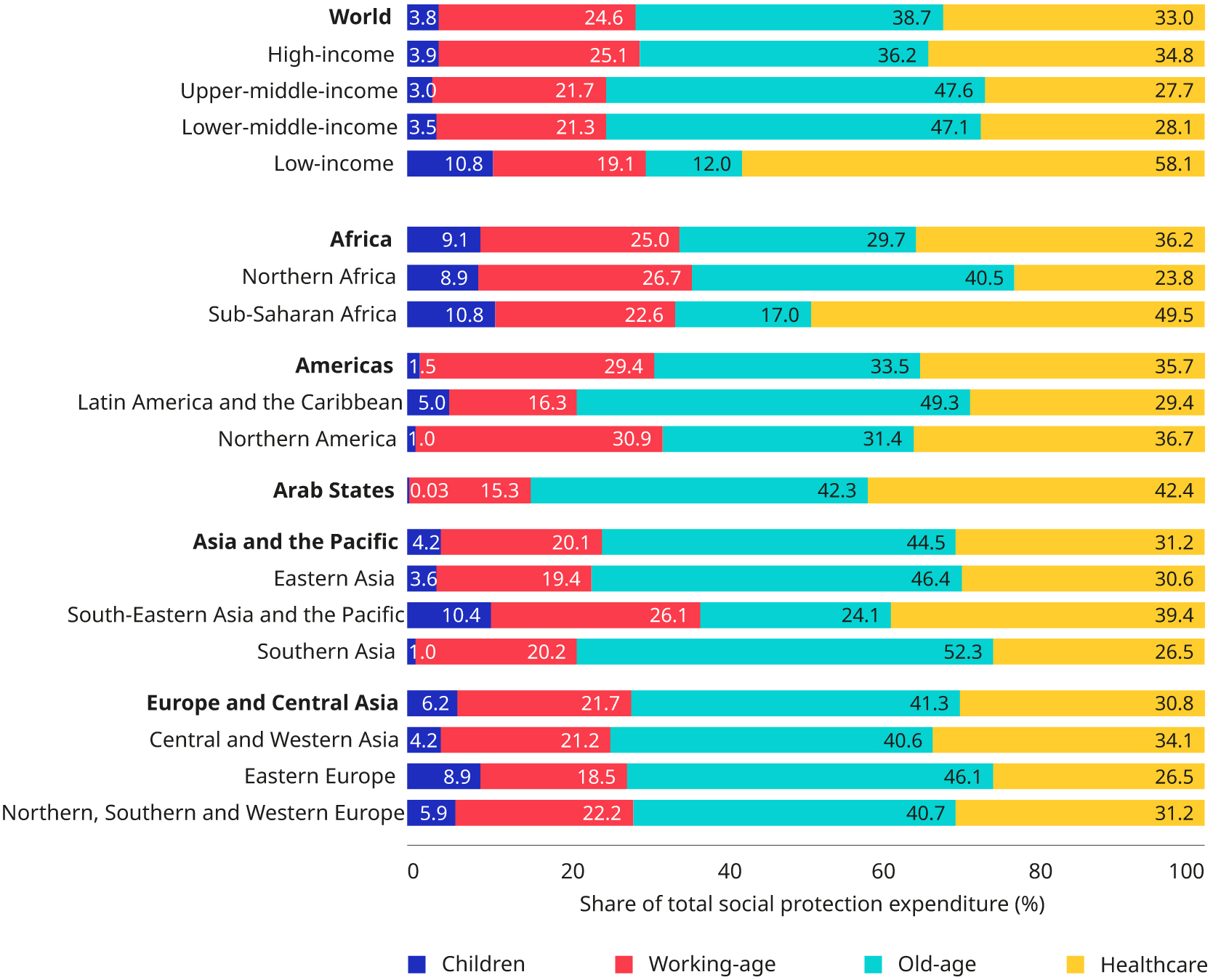

Analysing the structure of social protection expenditure across different benefits reveals distinct patterns (figure 3.12). Globally, the bulk of total social protection spending is devoted to old-age pensions (38.7 per cent) and healthcare (33.0 per cent). The remainder is distributed among benefits for the working-age population (24.6 per cent) and children (3.8 per cent). However, significant variations emerge across country income levels. For instance, low-income countries allocate the largest part of their expenditure to healthcare, while the share allocated to old-age pensions is relatively smaller given their demographic structures. In stark contrast, lower-and upper-middle-income countries assign almost half of their social protection expenditure to old-age pensions (47.1 per cent and 47.6 per cent, respectively), but a relatively small share to children. Similarly, in high-income countries, old-age benefits account for the largest share of social protection expenditure at 36.2 per cent, followed by healthcare at 34.8 per cent. Across regions, Southern Asia allocates over half of its social protection expenditure to old-age benefits, whereas Sub-Saharan Africa directs the highest proportion of expenditure towards healthcare, at 49.5 per cent.

Figure 3.12 Distribution of social protection expenditure by social protection guarantee, 2023 or latest available year, by region, subregion and income level (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by GDP. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

Source: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ADB, GSW, IMF; OECD; UNECLAC; WHO, national sources.

3.4.2 Filling the social protection floor financing gap

Current levels of expenditure are clearly insufficient to close coverage and adequacy gaps. In low-and middle-income countries, there is an urgent need to ensure that all residents and children should have access to at least a social protection floor.

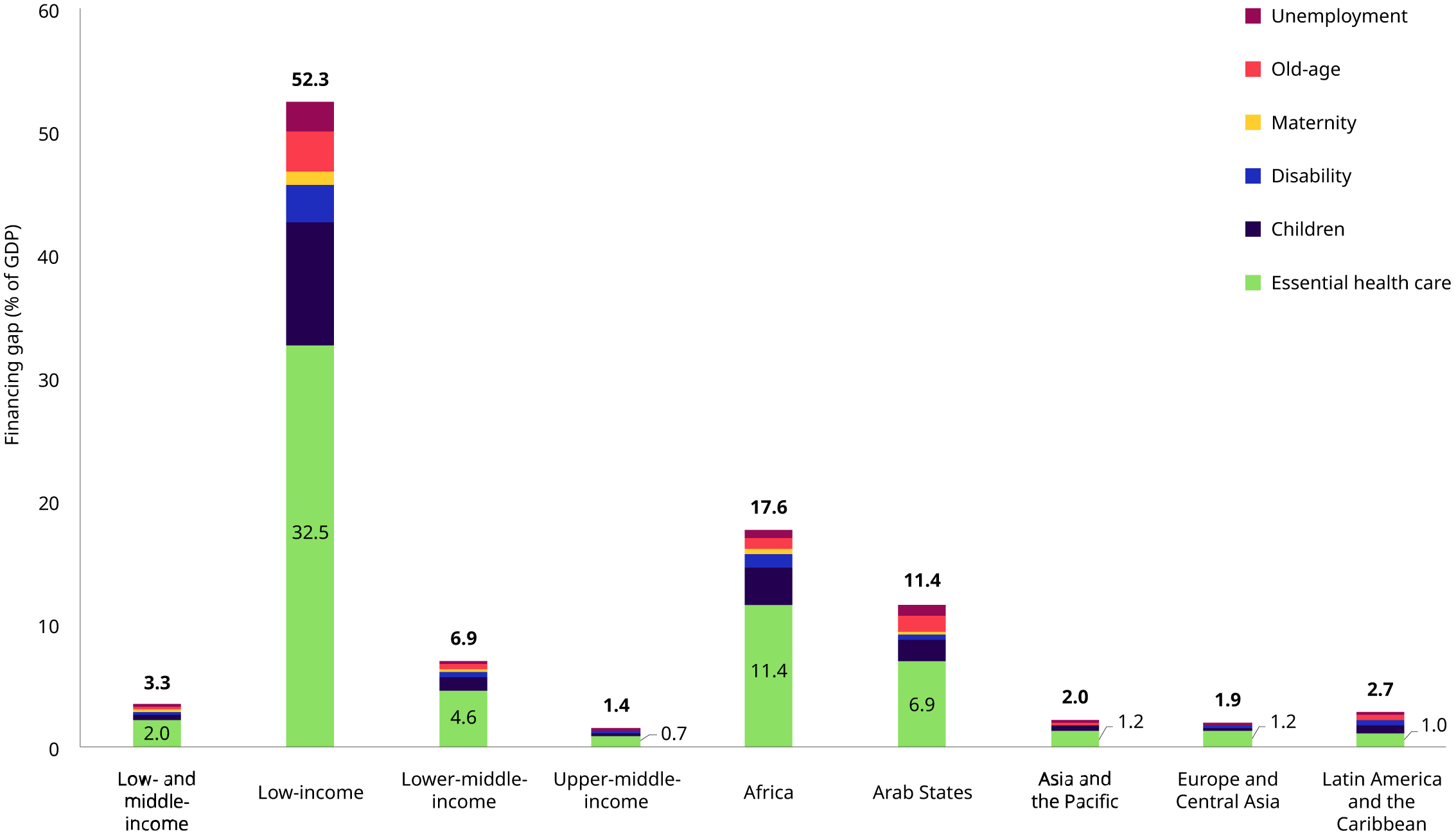

It is encouraging that some developing countries have already successfully achieved universal social protection coverage for some guarantees. However, based on data for 133 low-and middle-income countries, the ILO has estimated that the financing gap to ensure a social protection floor for all – including access to at least a basic level of income security (SDG target 1.3) and access to essential healthcare (SDG target 3.8) – persists in most low-and middle-income countries (Cattaneo et al., 2024). For low-and middle-income countries, the financing gap equals 3.3 per cent of GDP annually (figure 3.13), with 2 per cent of GDP required for essential healthcare and 1.3 per cent for the five key social protection cash benefits. Of this, 0.6 per cent of GDP is required for child benefits, 0.3 per cent for old-age pensions, 0.2 per cent for disability benefits, 0.2 per cent for unemployment benefits and 0.05 per cent for maternity benefits.

In absolute terms, to fill this gap across all low-and middle-income countries, countries need to mobilize an additional US$1.4 trillion per year. Most of these funds (60.1 per cent) are required for essential healthcare, followed by 17.8 per cent for child benefits, 8.3 per cent for old-age pensions, 7.1 per cent for disability benefits, 5.2 per cent for unemployment benefits and 1.5 per cent for maternity benefits.

The global perspective masks significant disparities among national income groups. Low-income countries face the largest financing gap, amounting to US$308.5 billion, or 52.3 per cent of their GDP. Among regions, Africa has the largest financing gap to bridge for achieving a social protection floor: 17.6 per cent of the region’s GDP per year. By contrast, in Europe and Central Asia, the financing gap as a proportion of GDP is the lowest across regions and country income groups. It stands at 1.9 per cent of GDP per year, with 1.2 per cent of GDP for essential healthcare and 0.6 per cent for the five social protection cash benefits.

Figure 3.13 Financing gap for achieving universal social protection coverage per year, by social protection benefit, by region and income level, 2024 (percentage of GDP)

Source: Cattaneo et al. (2024).

3.4.3 Ensuring equitable and sustainable social protection financing for a just transition

Options for equitable fiscal space expansion

Different options exist to increase fiscal space for social protection (Ortiz et al. 2019). When designing social protection financing strategies, governments can address increasing climate inequalities within and between countries, to support people least responsible for climate change and least equipped to adapt (Chancel, Bothe and Voituriez 2023).

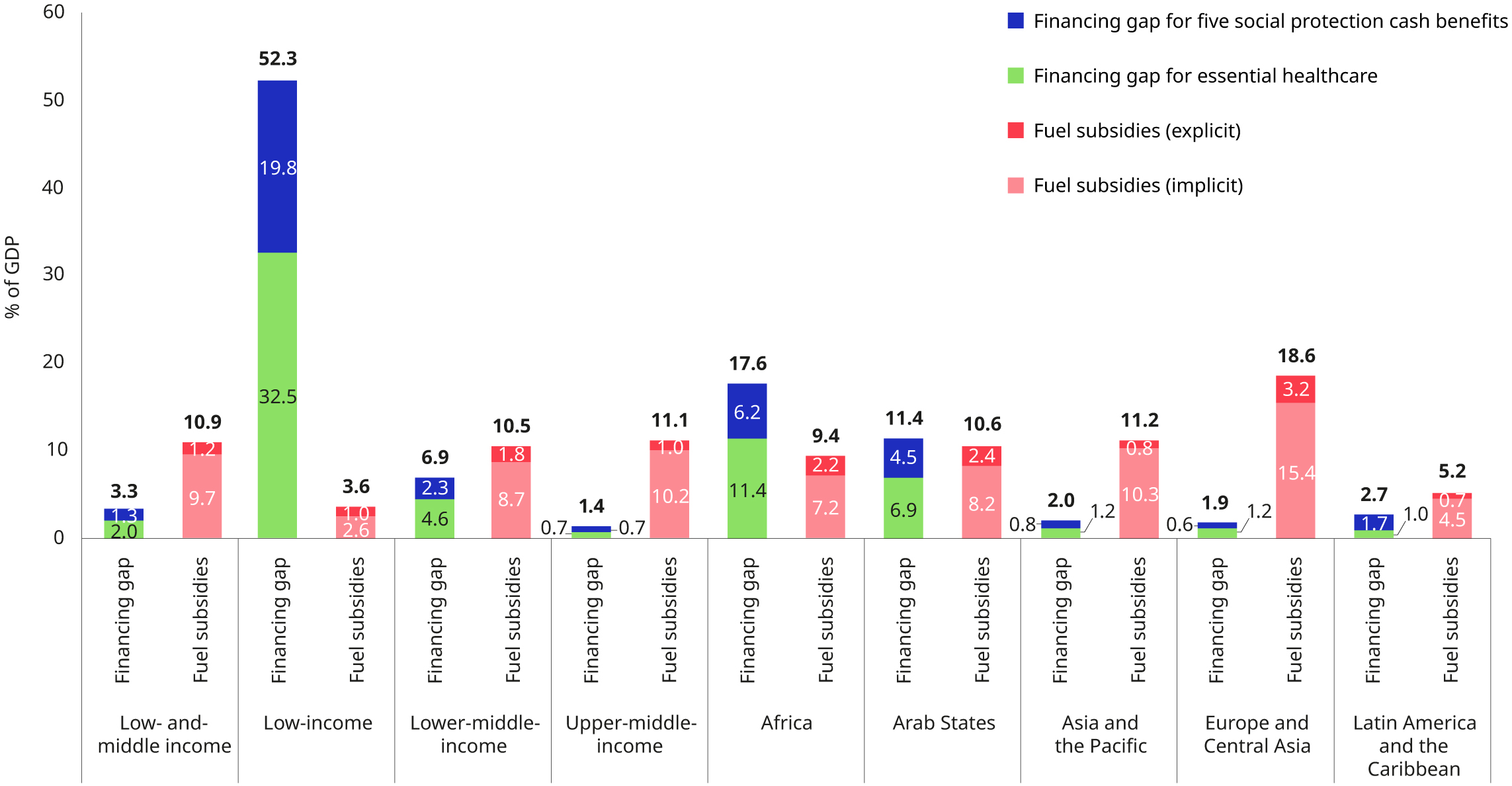

Reducing inequalities within countries: Filling social protection floor financing gaps through revenues from explicit and implicit fossil fuel subsidies

Reducing the unequal impact of climate change on national populations requires the promotion of progressive taxation and social policies, including by taxing those that consume and produce more CO2. One option is the progressive removal of fossil fuel subsidies (explicit fossil fuel subsidies) or the increase in the price of carbon-intensive goods and services through a carbon tax or emissions trading system (implicit fossil fuel subsidies). In the short run, social protection systems need to be already in place to cushion the adverse impacts of fossil fuel subsidies removal on households. In the long run, reinvesting the savings and/or revenues from such reforms into social protection can increase the coverage and adequacy of benefits, win public support for the reforms, and even reduce poverty and inequality to below pre-reform levels (see section 2.2.1).

Removing explicit and implicit fuel subsidies can contribute to filling social protection floor financing gap. Across low-and-middle-income countries, explicit and implicit fuel subsidies represent 1.2 and 9.7 per cent of GDP, respectively (Cattaneo et al. 2024). These subsidies compare with an overall social protection financing gap of 3.3 per cent of GDP (figure 3.14).

However, significant variations exist across countries and regions. The potential for filling financing gaps using fiscal space created by fossil fuel subsidy reforms is generally greater in middle-income countries and limited in low-income countries. Middle-income countries tend to spend more on explicit fuel subsidies. They also produce and consume more carbon-intensive goods and services (i.e., they have higher carbon emissions), which raises the revenue potential from removing implicit subsidies through taxation or emissions trading systems. On the other hand, both spending on explicit subsidies and carbon emissions are generally low in low-income countries. Thus, in these countries explicit and implicit fuel subsidies represent only 1.0 per cent and 2.6 per cent of GDP, respectively. This further confirms the conclusions that low-income countries cannot fill their social protection floor financing gaps from domestic resources alone and will require international assistance (Cattaneo et al. 2024) (box 3.6).

Middle-income countries could consider repurposing explicit fuel subsidies or using carbon pricing to fill their financing gaps. Options for reinvesting such resources include extending coverage, increasing benefit adequacy or raising the comprehensiveness of social protection.

However, not all reinvestment options will automatically cushion households from any negative impacts caused by fossil fuel subsidies removal or carbon taxes. The most appropriate option depends on the parameters of the existing system and the estimated impact of the reforms on prices and households (see section 2.2.1).

Figure 3.14 Comparison between the resources allocated to explicit and implicit fuel subsidies and the financing gap for a social protection floor, 2024 (percentage of GDP)

Source: Cattaneo et al. (2024) based on data from the IMF Climate Change Indicators Dashboard, accessed February 2024.

Box 3.6 Expanding fiscal space through the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions

|

The Global Accelerator,1 launched in 2021 by the United Nations Secretary-General, seeks to address multiple challenges, including climate change, that are erasing development progress, and accelerate the achievement of the SDGs, including by creating decent jobs and extending social protection. The Global Accelerator comprises three interconnected pillars – integrated policies, financing and enhanced multilateral coordination. The financing pillar connects integrated policies with financing strategies. This includes: (a) ensuring that ministries of economy and finance pursue macroeconomic policies that foster social investment; (b) inviting public development banks and the private sector to contribute through policy loans or increasing the social impact of current investments; (c) ensuring that international financial institutions protect and extend public social spending. The Global Accelerator also supports fiscally constrained countries by mobilizing more international finance (such as official development assistance and climate funds) for creating decent jobs and extending social protection. |

Reducing inequalities between countries: Leveraging international climate finance for social protection

Climate inequalities between countries imply differentiated mitigation responsibilities and for countries that are larger net contributors to global warming to provide financial assistance to countries with limited adaptation capacity (Chancel, Bothe and Voituriez 2023). This principle is enshrined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which defines climate finance as financing that seeks to support climate change mitigation and adaptation action (UNFCCC 2023a).

Social protection is increasingly recognized at climate negotiations (UN 2023c; 2023a; 2023b) and in the literature (Hallegatte et al. 2024; Malerba 2022) as making a key contribution to climate change mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage response. Hence, international climate financing should contribute towards building social protection systems. This applies especially to low-income countries vulnerable to climate risks and where filling financing gaps from domestic resources is challenging. Sources of climate finance are diverse, comprising regional and multilateral development banks, climate funds, international and regional financing partnerships, and financing arrangements for addressing losses and damages.

However, to date, only very limited international climate finance has been directed towards social protection (Aleksandrova 2021). More progress is required to mainstream climate change objectives in social protection policy and vice versa. For example, it is important to include social protection and health in nationally determined contributions and national adaptation plans. This is a precondition for directing multilateral climate financing to social protection. However, such integration remains limited: only 20 out of 196 nationally determined contributions assign a role to social protection in climate action, and even fewer cite concrete actions for systems strengthening (Crumpler et al., forthcoming). Funding institutions need to recognize the role of social protection in climate action and explicitly reference it in their investment frameworks. On the other hand, national governments and climate fund applicants must also realize the potential of social protection and insist on fund allocation for social protection systems strengthening (Aleksandrova 2021).

Anticipating future needs and financial preparedness for sustainable financing

Social protection financing strategies must adapt to the medium-and long-term impacts of climate change on needs, revenues, contributions and costs. Furthermore, pre-arranged financing is paramount if social protection systems are to provide income security and healthcare during extreme events (see section 2.1). Estimates show that only 2–3 per cent of crisis financing is pre-arranged (Crossley et al. 2021), indicating that most responses are ad hoc and likely insufficient.

Social security schemes should factor climate risks into their actuarial valuations and reserves for financial sustainability (ILO, ISSA and OECD 2023). There are increasingly accurate and comprehensive forecasts of long-term climate change, the effects of which can be considered by actuarial valuations to ensure fund resilience (see section 4.3.9). This requires needs, cost and contributions modelling and anticipation. For social health protection schemes, actuarial, epidemiological and climate modelling expertise could be combined to strengthen the financial resilience of schemes (ILO 2024f), given that these may face increased demand linked to the intensification of climate-related shocks.

Greater integration of disaster-risk financing instruments in social protection financing can enable a more effective and sustainable response to disasters (UNICEF 2023 a). Instruments may include contingency budgets, reserve funds and contingency credits or loans. National governments may also make use of regional sovereign insurance mechanisms such as the Africa Risk Capacity and channel payouts through the social protection system. Disaster-risk financing is usually embedded in a country’s legal, policy and institutional arrangements, and better linkages with social protection systems must be developed, including through contingency plans for support during climate-related disasters (UNICEF 2023a). Crucially, these additional sources should not displace other sources of financing necessary for ensuring sustainable and equitable social protection financing.

.3.5 Adapting and strengthening institutional and operational capacities

To ensure that social protection can play its role in supporting inclusive climate action and a just transition (Chapter 2), its systems need to be strengthened and adapted, especially in countries with nascent social protection institutions.

Universal and adaptive social protection requires two core actions (see figure 3.15):

-

enhance institutional and operational capacities and processes to meet current and future needs; and

-

adapt the system to new and increasing demands resulting from direct climate change and transition impacts.

Attaining this dual objective will ensure institutional readiness, thereby reducing sole reliance on reactive, untimely and fiscally inefficient measures and inadequate stop-gap solutions (ISSA 2022).

Figure 3.15 Selected actions to strengthen and adapt institutional and operational capacities

|

Dimension |

Actions to strengthen the social protection system |

Additional actions for climate action and a just transition |

|

|

Policy and governance |

Policy, strategy and legal frameworks |

Social protection policies and strategies formulated, regularly updated and implemented through participatory national dialogue |

Integration of social protection and climate policies and strategies, legal frameworks adjustments accordingly and needs assessments |

|

Governance and coordination |

Social protection institutions are well resourced and well coordinated with other sectors |

Coordination with other sectors pertinent to just transition, climate change adaptation and disaster response |

|

|

Financing |

Sustainable and equitable financing strategies |

Costing scenarios adjusted to climate and transition impacts and pre-arranged financing |

|

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

Policymaking informed by evidence on process and impact |

Climate-specific performance indicators |

|

|

Scheme design |

Eligibility and qualifying conditions |

Eligibility criteria set in line with international standards |

Capacity for flexible adjustment of criteria to respond to new needs |

|

Adequacy: level, value, frequency and duration |

Level and duration of benefits and quality of services aligned with international standards |

Capacity for short-term and long-term adaptation of benefit parameters to ensure adequacy |

|

|

Comprehensiveness |

Full range of life-cycle risks covered, with linkages to complementary services |

Linkages to active green and climate-sensitive labour market policies, skills, agricultural support and insurances |

|

|

Operations and deliver |

Outreach, enrolment, contribution collection, benefit delivery, grievance mechanisms |

Inclusive and on-demand access across the delivery chain and progressive digitalization of processes |

Standard operating procedures and contingency plans for service continuity and surge capacity for increased demands |

|

Information systems |

Interoperable social protection information systems, including national single registries |

Linkages to disaster risk management and humanitarian registries, early warning system and geographic information system databases |

3.5.1 Policy and governance: Increasing coherence and coordination between social protection and climate policies

Social protection policies and strategies, guided by social dialogue, ensure the progressive strengthening of social protection systems. These should also inform legal framework reforms to make sure that rights and obligations align with international standards. Reinforcing governance mechanisms includes effective coordination with other sectors, ensuring sustainable and equitable financing strategies, regular monitoring, and evaluation of implementation, processes and impact that can inform policy reform processes.

The following actions can help prepare social protection systems and adapt them to better facilitate inclusive climate action and a just transition (box 3.7):

-

Incorporating climate risk in addition to life-cycle risks in national social protection policies and strategies based on an assessment of the socio-economic impacts of climate policies and the climate crisis (Costella and McCord 2023). Adjustments should be underpinned by inclusive dialogue with social partners and other representatives of persons concerned, including indigenous communities (Cookson et al., forthcoming; ILO 2020i).

-

Defining the role of social protection in nationally determined contributions and national adaptation plans, disaster risk management strategies and/or (just) transition plans.

-

Ensuring legal frameworks allow for (temporary) adjustments of eligibility criteria, benefit levels and duration when crises occur.

-

Including ministries of labour and social affairs/development/protection in just transition planning and enhancing coordination with ministries of environment and energy, finance, economy and planning, and agriculture.

-

Assigning clear roles and responsibilities and standard operating procedures to social protection, disaster risk management and humanitarian actors in disaster response contexts (ISSA 2023a).

-

Including impacts of climate change and climate policies in the costing of schemes and ensure (pre-arranged) availability of financing (section 3.4.3).

-

Adding performance indicators for resilience building, responsiveness to climate risks and climate policies in social protection monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

Box 3.7 Institutionalizing social protection responses to climate shocks in Azerbaijan

|

Azerbaijan’s national social protection system has implemented emergency responses to smaller-scale localized natural disasters for several years. The current five-year National Socio-Economic Strategy includes activities to replace these ad hoc measures with institutionalized social protection responses to provide reliable and effective support to people affected by climate-related hazards. This includes defining legal provisions, guidelines and technical mechanisms for determining appropriate eligibility criteria, flexible and timely financing arrangements, rapid payment and clear roles and responsibilities of the institutions in implementing and coordinating the response through the social protection system. |

Source: UNICEF (forthcoming).

3.5.2 Scheme design: adaptable eligibility criteria and benefit levels in the face of changing needs

When designing schemes, eligibility criteria, benefit levels, duration and frequency should be set in line with international standards and in a way that progressively extends coverage and adequacy.

In addition, adaptations to eligibility criteria and benefit levels can help address changing needs amidst short-, medium-and long-term climate and transition risks:

-

Automatic triggers. Introducing predefined mechanisms that can rapidly adjust eligibility criteria, benefit levels and duration through existing reserves or additional tax financing (for example, in the United States, see section 4.2.6) when shocks hit, ensuring a quick and “automatic” response.

-

Ad hoc measures. When in-built mechanisms are not sufficient or established, ad hoc measures can adapt eligibility criteria and increase benefit levels to ensure additional horizontal and vertical expansions of the system during crises like floods or cyclones and for cushioning impacts of climate policies (ILO 2024f).

-

Long-term benefit adequacy. All benefits should be indexed to appropriate inflation benchmarks and adjusted to evolving needs – for example, to upwards pressure on food prices due to prolonged climate impacts (Jafino et al. 2020).

-

Climate-sensitive health and sickness benefits. These should guarantee continuity of essential medical services at least and include emergency care, injuries, rehabilitation and chronic disease management, which are still insufficiently financed in many countries.

Social protection benefits should also be linked to complementary services. In the context of climate change and the transition, linkages with green active labour market policies, skills development, climate-sensitive agricultural support or insurance are of particular importance (see Chapter 2).

3.5.3 Operations and delivery: enabling resilience and responsiveness

Institutions mandated with the administration and delivery of social protection benefits can implement the following strategies to enable service continuity and enhance their capacity to quickly respond to emerging needs (ISSA 2022; TRANSFORM 2020):

-

Conduct risk assessments and scenario modelling to evaluate the impact of different climate hazards on benefits and service delivery, in particular to reach vulnerable groups (ISSA 2023a).

-

Develop contingency plans and standard operating procedures for service delivery during emergencies, including in new locations, rapid enrolment, alternate payment approaches and surge capacity.

-

Digitalize the administration of benefits, including solutions for needs identification, outreach, registration, enrolment and payment. A mix of manual and digital delivery options inclusive of groups with low digital literacy or access to technologies might be required (see box 3.8).

-

Adapt communication plans and grievance redress mechanisms when the social protection system responds to climate-related emergencies or plays a role in transition packages (for example, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies or industry closures) to uphold accountability, transparency and acceptability.

Investment in information systems is also essential for an efficient and effective administration of the social protection system (Barca and Chirchir 2019; Pignatti, Galian and Peyron Bista 2024). This includes the development of national single registries and ensuring the interoperability of social protection information systems with other public administration services, including civil registries and vital statistics. Data privacy and security as well as sensitivity to exclusion risks must be prioritized.

High-quality and inclusive information systems enable social protection to play its role in climate action and a just transition as they allow all the people affected by climate emergencies or transition policies to be reached (Chapter 2). Additional actions – such as integrating social protection information systems with early warning systems, geographic information systems and nowcasting models using high-frequency data – can trigger more effective shock responses. Pre -arranged data-sharing agreements with entities in charge of disaster risk management and humanitarian databases can further enhance more coordinated responses (Barca and Chirchir 2019).

Box 3.8 Responding to Hurricane Katrina: Rudimentary and “low-tech” yet vital action

|

When Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana, United States, in 2005, pre-existing vulnerabilities associated with class and race inequalities were exacerbated (Garton Ash 2005; Brooks 2005). However, the United States Social Security Administration responded quickly and supported 1.6 million affected beneficiaries by establishing the following:

Technological advances are important but might not always be available during extreme events, hence low-tech human resource support and payment modalities may still play a response role. |

Sources: Government of the United States (2015; 2005); Orton (2015).